The Higher Education Landscape Under Apartheid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVEN Confers a Total of 64 Doctoral Degrees During 2019 Academic Year Cont

SEPTEMBER 2019 UNIVEN confers a total of Read inside UNIVEN confers a total of 64 Doctoral degrees 1 64 Doctoral degrees during UGO plants Five trees to celebrate 3 Arbour Day MEC Thandi Moraka encourages South Africans to continuously teach their 4 2019 academic year children about our history, culture, heritage and tradition Mr and Miss UNIVEN Heritage 2019/20 crowned 6 ABASA launches a student chapter at UNIVEN 7 Black Lawyers Association Student Chapter paves way for UNIVEN Law 9 students to legal fraternity Dr Edwin Madala wins a prestigious NRF award as an Emerging researcher 10 of the year Centre for Biokinetics, Recreation and Sport Science honours the late Prof 11 Lateef Amusa Department of Justice and Correctional Services should partner with universities to create ethical 12 leaders Netshivhambe represents Ghana at Asia Youth International Model United 13 Nations Symposium in Malaysia Prof Natasha Potgieter is the recipient of the CEO Global’s Pan Africa’s Most 13 Influential Woman in Business and Government AND Titans International Relations Directorate Hosts Buddy Programme Groups 14 PhD graduates of first session posing for a group photo in front of Life Sciences building UNIVEN FM celebrates Twenty-Two years 15 of broadcasting “Our doctoral degree output for this Spring to the economy of the country since its graduation ceremony is the highest number establishment regardless of the challenges Ndivhuho Luvhengo scooped the Best of doctoral degrees ever produced by faced by the Institution from time to time. African Jazz Song at the SATMA14 15 this University. We are very pleased about He told the audience that UNIVEN continues this achievement and would like to thank to be on an upward trajectory regarding its The impact of digital media towards print media has cost media academic, administrative and service staff research output. -

Report on the State of the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences in South African Universities

REPORT ON THE STATE OF THE ARTS, HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN SOUTH AFRICAN UNIVERSITIES Prepared for the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Ahmed Essop December 2015 1 1. Introduction This report on the trends in, and the size and shape of, the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences (AHSS) at South African universities between 2000 and 2013, which was commissioned by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (AWMF), has the purpose of informing the Mellon Foundation’s “policy and practice on grant making” in AHSS at South African universities in line with the Foundation’s new Strategic Plan, which calls for “a bold and creative approach to grant making, responsive to promising new organisations as well as to established institutions” and which seeks “a larger family of grantees to underscore the potential contribution of the humanities and arts to social mobility”. The report is based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis, including unstructured interviews with selected academic and institutional actors in AHSS. Furthermore, in line with the Mellon Foundation’s focus, which does not include professional fields in the humanities and social sciences, the analysis focuses on the arts and non-professional humanities and social sciences (ANPH), as outlined in Appendix Two. 3. Part One: Size and Shape of AHSS in South African Universities 3.1 Background The role and status of AHSS has been the subject of public debate in the recent past as a result of two studies – the Academy of Science of South Africa’s (ASSAf) Consensus Study on the State of the Humanities in South Africa (ASSAf, 2011) and the Charter for the Humanities and Social Sciences (DHET, 2011) commissioned by the Minister of Higher Education and Training. -

The Future of This Country Is in Your Hands – Premier

UniversityUniversity ofof VVendaenda Nendila NEWSLETTER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VENDA MAY / JUNE 2015 The future of this country Read inside Univen celebrates Africa Day 2 Univen is waiting – apply NOW is in your hands – Premier for 2016 admission 2 Univen occupies its rightful place in society – Chancellor Chancellor Motlanthe confers Univen celebrates Youth Day degrees on more than 2 000 students 3 “The future of this country is in your hands, so New faces at Univen 3 make education a priority.” This was the message from Limpopo Premier First-ever research indaba at Univen 4 Stanley Mathabatha at Youth Day celebration at the Univen stadium on 16 June. International intern at Institute “The youth of today should simply understand for Rural Development 4 that they are not a generation of 1976. You are a special unique generation and most of you were Univen hosts the most successful born after freedom and democracy. More so, you career exhibition have your own set of challenges, unlike the youth 4 of 1976. The generation of 1976 existed in its own material condition of its time and they existed under Talking internationalisation in Brazil 4 apartheid. “It was politically correct for the youth of 1976 Vice Chancellor hosts social to burn schools then. As the generation of post dialogue platform liberation South Africa, your challenges are Univen Transformation different from those of 1976. You are a very special Charter launched generation because your schools are not receiving Univen – a diverse community 5 Bantu education and not forced to have Afrikaans as a medium of instruction because it was the Let’s clean up! language of the oppressor. -

Vigilantism V. the State: a Case Study of the Rise and Fall of Pagad, 1996–2000

Vigilantism v. the State: A case study of the rise and fall of Pagad, 1996–2000 Keith Gottschalk ISS Paper 99 • February 2005 Price: R10.00 INTRODUCTION South African Local and Long-Distance Taxi Associa- Non-governmental armed organisations tion (SALDTA) and the Letlhabile Taxi Organisation admitted that they are among the rivals who hire hit To contextualise Pagad, it is essential to reflect on the squads to kill commuters and their competitors’ taxi scale of other quasi-military clashes between armed bosses on such a scale that they need to negotiate groups and examine other contemporary vigilante amnesty for their hit squads before they can renounce organisations in South Africa. These phenomena such illegal activities.6 peaked during the1990s as the authority of white su- 7 premacy collapsed, while state transfor- Petrol-bombing minibuses and shooting 8 mation and the construction of new drivers were routine. In Cape Town, kill- democratic authorities and institutions Quasi-military ings started in 1993 when seven drivers 9 took a good decade to be consolidated. were shot. There, the rival taxi associa- clashes tions (Cape Amalgamated Taxi Associa- The first category of such armed group- between tion, Cata, and the Cape Organisation of ings is feuding between clans (‘faction Democratic Taxi Associations, Codeta), fighting’ in settler jargon). This results in armed groups both appointed a ‘top ten’ to negotiate escalating death tolls once the rural com- peaked in the with the bus company, and a ‘bottom ten’ batants illegally buy firearms. For de- as a hit squad. The police were able to cades, feuding in Msinga1 has resulted in 1990s as the secure triple life sentences plus 70 years thousands of displaced persons. -

Faculty of Health Sciences Prospectus 2021 Mthatha Campus

WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES PROSPECTUS 2021 MTHATHA CAMPUS @WalterSisuluUni Walter Sisulu University www.wsu.ac.za WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY MTHATHA CITY CAMPUS Prospectus 2021 Faculty of Health Sciences FHS Prospectus lpage i Walter Sisulu University - Make your dreams come true MTHATHA CAMPUS FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES PROSPECTUS 2021 …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… How to use this prospectus Note this prospectus contains material and information applicable to the whole campus. It also contains detailed information and specific requirements applicable to programmes that are offered by the campus. This prospectus should be read in conjunction with the General Prospectus which includes the University’s General Rules & Regulations, which is a valuable source of information. Students are encouraged to contact the Academic Head of the relevant campus if you are unsure of a rule or an interpretation. Disclaimer Although the information contained in this prospectus has been compiled as accurately as possible, WSU accepts no responsibility for any errors or omissions. WSU reserves the right to make any necessary alterations to this prospectus as and when the need may arise. This prospectus is published for the 2021 academic year. Offering of programmes and/or courses not guaranteed. Students should note that the offering of programmes and/or courses as described in this prospectus is not guaranteed and may be subject to change. The offering of programmes and/or courses is dependent on viable -

Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities

Original Scientific Articles Medical Education Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities Jehu E. Iputo, MBChB, PhD ABSTRACT Outcomes To date, 745 doctors (72% black Africans) have graduated Introduction The South African health system has disturbing in- from the program, and 511 students (83% black Africans) are currently equalities, namely few black doctors, a wide divide between urban enrolled. After the PBL/CBE curriculum was adopted, the attrition rate and rural sectors, and also between private and public services. Most for black students dropped from 23% to <10%. The progression rate medical training programs in the country consider only applicants with rose from 67% to >80%, and the proportion of students graduating higher-grade preparation in mathematics and physical science, while within the minimum period rose from 55% to >70%. Many graduates most secondary schools in black communities have limited capacity are still completing internships or post-graduate training, but prelimi- to teach these subjects and offer them at standard grade level. The nary research shows that 36% percent of graduates practice in small Faculty of Health Sciences at Walter Sisulu University (WSU) was towns and rural settings. Further research is underway to evaluate established in 1985 to help address these inequities and to produce the impact of their training on health services in rural Eastern Cape physicians capable of providing quality health care in rural South Af- Province and elsewhere in South Africa. rican communities. Conclusions The WSU program increased access to medical edu- Intervention Access to the physician training program was broad- cation for black students who lacked opportunities to take advanced ened by admitting students who obtained at least Grade C (60%) in math and science courses prior to enrolling in medical school. -

The Vudec Merger: a Recording of What Was and a Reflection on Gains and Losses

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository The Vudec merger: a recording of what was and a reflection on gains and losses H. M. van der Merwe Department of Further Teacher Education University of South Africa Pretoria, South Africa e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The restructuring of higher education in South Africa is being dually steered by an equity and a merit imperative. In the move towards creating a single dedicated distance-education institution, the outcome of the merged incorporation of Vista University Distance Education Campus (Vudec) into the University of South Africa (UNISA) implied the obliteration of the Vudec culture. This has warranted the recording of the Vudec culture based on the valid need to document the existence of an institution of higher education over a period of 21 years. It has also warranted an assessment of gains and losses as a result of the merger. Based on literature and a qualitative study undertaken in Vudec, the Vudec institutional culture has been documented and gains and losses for Vudec students and staff determined. It is argued that although significant gains were made, such as better opportunities for students and staff due to improved resources, a serious loss has been incurred in the disappearance of the under-developed student corps of practising teachers. Apart from not fully accomplishing the equity goal, this loss also jeopardises merit achievements. INTRODUCTION At the end of the apartheid era in 1994 the quality of South African higher education institutions differed significantly across racial lines with historically black institutions falling far behind the historically white universities with regard to funding, facilities and international reputation (NCHE 1996, 9±23). -

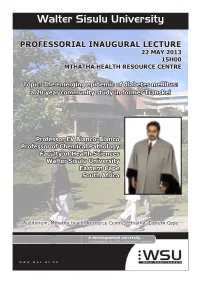

Walter Sisulu University

Walter Sisulu University PROFESSORIAL INAUGURAL LECTURE 22 MAY 2013 15H00 MTHATHA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE Topic: The emerging epidemic of diabetes mellitus: a 20 year community study in former Transkei Professor EV Blanco-Blanco Professor of Chemical Pathology Faculty of Health Sciences Walter Sisulu University Eastern Cape South Africa Auditorium, Mthatha Health Resource Centre, Mthatha, Eastern Cape www.wsu.ac.za WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY (WSU) DEPARTMENT OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES TOPIC “THE EMERGING EPIDEMIC OF DIABETES MELLITUS: A 20-YEAR COMMUNITY STUDY IN THE FORMER TRANSKEI” BY ERNESTO V. BLANCO-BLANCO PROFESSOR OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY DATE: 22 MAY 2013 VENUE: UMTATA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE 3 4 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION DIABETES MELLITUS Definition Historical background CLASSIFICATION OF DIABETES MELLITUS DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES MELLITUS RISK FACTORS AND PREDISPOSING CONDITIONS FOR DIABETES COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE GLOBAL PREVALENCE & GLOBAL BURDEN OF DIABETES THE AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE SOUTH AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS CONSEQUENCES OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES IMPLICATIONS OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES FOR HEALTH PLANNING DIABETES PREVENTION AS STRATEGY CONTROL OF THE CURRENT BURDEN OF DIABETES CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES 5 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION Chemical Pathology, Diabetes Mellitus and the Former Transkei I am a Chemical Pathologist by training. The term ‘pathology’ derives from the Greek words “pathos” meaning “disease” and “logos” meaning “a treatise”. Pathology is a major field of Medicine that deals with the essential nature of diseases, their processes and consequences. A medical doctor that specializes in pathology is known as ‘a pathologist’. Chemical Pathology is that branch of Pathology, which deals specially with the biochemical basis of diseases and the use of biochemical tests carried out at hospital laboratories on the blood and other body fluids to provide support to clinicians. -

Download Download

Journal of International Education Research – Second Quarter 2013 Volume 9, Number 2 Restructuring And Mergers Of The South African Post-Apartheid Tertiary System (1994-2011): A Critical Analysis Nelda Mouton, Ph.D., North-West University, South Africa G. P. Louw, Ph.D., North-West University, South Africa G. L. Strydom, Ph.D., North-West University, South Africa ABSTRACT Socio-economic and vocational needs of communities, governments and individuals change over the years and these discourses served as a compass for restructuring of higher institutions in South Africa from 1994. Before 1994, the claim to legitimacy for government policies in higher education rested on meeting primarily the interests of the white minority. From 1996 onwards, the newly established government considered education a major vehicle of societal transformation. The main objective had been to focus on reducing inequality and fostering internationalisation. Therefore, the rationale for the restructuring of South African universities included a shift from science systems to global science networks. Various challenges are associated with restructuring and include access, diversity, equity and equality. Thus, the restructuring and mergers between former technikons and traditional universities were probably the most difficult to achieve in terms of establishing a common academic platform, as transitional conditions also had to be taken into account and had a twin logic: It was not only the legacy of apartheid that had to be overcome but the incorporation of South Africa into the globalised world was equally important as globalisation transforms the economic, political, social and environmental dimensions of countries and their place in the world. Initially, the post-apartheid higher education transformation started with the founding policy document on higher education, the Report of the National Commission on Higher Education and this report laid the foundation for the 1997 Education White Paper 3 on Higher Education in which a transformed higher education system is described. -

Winkie Direko-A Political Leader in Her Own Right?

JOERNAAL/JOURNAL TWALA/BARNARD WINKIE DIREKO-A POLITICAL LEADER IN HER OWN RIGHT? Chitja Twala* and Leo Barnard** 1. INTRODUCTION To record merely that Winkie Direko, present premier of the Free State Province, was born on 27 November 1929 in Bochabela (Mangaung) and to an average family, will be an inadequate prelude to assessing her community and political life, which had an impact on her political career. Her entry into full-time party politics after the April 1994 first non-racial democratic election in South Africa caused a great stir in the Free State Province, and no one ever expected that she would rise to the premiership position after June 1999. This article attempts to provide an accurate, scientific and historical assessment of Direko as a political leader in her own right amid serious criticisms levelled against her before and after her appointment as the province's premier. The article, however, does not tend to adopt a defensive stance for Direko, but rather to answer a repeatedly asked question in the political circles of the Free State Province on whether Direko is a political leader or not. The article extends beyond narrowly held views that Direko emerged to promi- nence after she had been inaugurated as the province's second woman premier in 1999. In the political arena, some critics within the ruling African National Congress (ANC) in the Free State Province claim that there is no testimonial that can more aptly describe her political leadership role. The fact that she occupied the premiership position for almost five years unlike her predecessors is testimony enough that she is a political leader in her own right. -

SENTECH SOC LIMITED Corporate Plan 2015-2018

SENTECH SOC LIMITED Corporate Plan 2015-2018 Presentation to the PPC on Telecommunications and Postal Services 14 April 2015 SENTECH SOC LTD Corporate 1 Plan 2015-2018 CORPORATE PLAN 1 FOREWORD 2 COMPANY PURPOSE 3 ALIGNMENT TO SHAREHOLDER PRIORITIES 4 PERFORMANCE REVIEW 5 MARKET OUTLOOK 6 BUSINESS STRATEGY: MTEF 2015 - 2018 7 STRATEGIC PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS 8 FINANCIAL PLAN 9 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS SENTECH SOC LTD Corporate Plan 2015-2018 2 FOREWORD • SENTECH hereby presents the Company’s Corporate Plan for the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2015 – 2018 which was tabled to Parliament by the Honorable Minister of Telecommunications and Postal Services. • The Corporate Plan was also submitted to National Treasury as required in terms of Section 52 of the PFMA and Treasury Regulation 29. • As one of the primary enablers of Government interventions in the Information Communication and Technology (“ICT”) sector, SENTECH’s business strategy is informed by and aligned to the Shareholder’s Medium Term Strategy Focus (“MTSF”) objectives, the Strategic Goals of the Department of Telecommunications and Postal Services (“DTPS”) for the same period, as well as the Company’s internal objectives as adopted by the Board of Directors from time to time. • For this MTEF period, the Board is re-committing SENTECH to a singular business strategy theme: “To provide and operate communications network services that enable all broadcasting and content services to be accessible by all South Africans” SENTECH SOC LTD Corporate Plan 2015-2018 3 FOREWORD: SENTECH of the Future • In order to ensure that the Company employs the required focus into the execution of the expanded business strategy, the Company has resolved to operate along a business unit structure and specifically, through four (4) distinct business units that will separately manage Broadcasting Signal Distribution Services, Digital Media Services, Connectivity Services and Public Safety Services. -

Creating Provinces for a New South Africa, 1993

NEGOTIATING DIVISIONS IN A DIVIDED LAND: CREATING PROVINCES FOR A NEW SOUTH AFRICA, 1993 SYNOPSIS As South Africa worked to draft a post-apartheid constitution in the months leading up to its first fully democratic elections in 1994, the disparate groups negotiating the transition from apartheid needed to set the country’s internal boundaries. By 1993, the negotiators had agreed that the new constitution would divide the country into provinces, but the thorniest issues remained: the number of provinces and their borders. Lacking reliable population data and facing extreme time pressure, the decision makers confronted explosive political challenges. South Africa in the early 1990s was a patchwork of provinces and “homelands,” ethnically defined areas for black South Africans. Some groups wanted provincial borders drawn according to ethnicity, which would strengthen their political bases but also reinforce divisions that had bedeviled the country’s political past. Those groups threatened violence if they did not get their way. To reconcile the conflicting interests and defuse the situation, the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum established a separate, multiparty commission. Both the commission and its technical committee comprised individuals from different party backgrounds who had relevant skills and expertise. They agreed on a set of criteria for the creation of new provinces and solicited broad input from the public. In the short term, the Commission on the Demarcation/Delimitation of States/Provinces/Regions balanced political concerns and technical concerns, satisfied most of the negotiating parties, and enabled the elections to move forward by securing political buy-in from a wide range of factions. In the long term, however, the success of the provincial boundaries as subnational administrations has been mixed.