The Lamp Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Just Like Us'?

‘Just like us’? Investigating how LGBTQ Australians read celebrity media Lucy Watson A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. A version of Chapter Nine appears in the book Gender and Australian Celebrity Culture (forthcoming), edited by Anthea Taylor and Joanna McIntyre. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Lucy Watson 25th September 2019 i Abstract In the 21st century, celebrity culture is increasingly pervasive. Existing research on how people (particularly women) read celebrity indicates that celebrity media is consumed for pleasure, as a way to engage in ‘safe’ gossip amongst imagined, as well as real, communities about standards of morality, and as a way to understand and debate social and cultural behavioural standards. The celebrities we read about engage us in a process of cultural identity formation, as we identify and disidentify with those whom we consume. Celebrities are, as the adage goes, ‘just like us’ – only richer, more talented, or perhaps better looking. But what about when celebrities are not ‘just like us’? Despite relatively recent changes in the representation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) life in the media, the world of celebrity is an overwhelmingly heterosexual one. -

Call for Council Peer Review Delayed How Big a Problem It Is When a Wealthy Nation Decides Nicky Boyette “At Approximately 9:30 A.M

This week’s Independent thinkers Protesters from across the United States have made it clear to their elected officials in Washington that having secret meetings to devise an incomplete and user-hostile healthcare plan is not in the best interest of citizens. Nor is repealing current What the health are you talking about? affordable healthcare benefits. About 50 people started arriving at 10 a.m. last Friday to drop off letters and speak with Rep. Steve Womack’s two field Many protesters have been arrested. workers at his mobile office in the Eureka Springs Chamber Office. Repeal and replacement of the Affordable Care Act stalled But residents of Gate City, Va., raised awareness out Monday night when Republicans couldn’t deliver the votes to even debate it. Pictured (l.-r.) are Peg Adamson, Edwige creatively by making a paper chain link for every child Denyszyn and Carolyn Amrit Knaus waiting in line with their designated numbers. PHOTO BY JAY VRECENAK and older citizen in Southwest Virginia who would lose health care if the Affordable Care Act were repealed. The chain was taken to Radford, Va., and added to 9th District names until there were 62,000 links in the 3-mile long paper chain so people could see with their own eyes Call for council peer review delayed how big a problem it is when a wealthy nation decides NICKY BOYETTE “At approximately 9:30 a.m. July 6, 2017, I walked into my its citizens are dispensable, or at least not worth helping Eureka Springs City Council convened a special office with Michele and Steve Schneider demanding me to when they get hurt or sick. -

January Front.Qxp

Them Crooked Vultures Review Will Pittsburgh’s Winter be a good one? Norah Jones’s New Album: Stylistic Page 8 Page 4 Reformation Page 8 TheThe StSt.. ClairionClairion Volume 11, Issue 2 - January 2010 - Upper St. Clair High School Pittsburgh, PA 15241 All the news that fits...And then some! Invisible Children gains visibility in the halls of USCHS By: Madeline Kushner the jewelry so interesting is the ence in the world. Actually, the association aims to establish Lord’s Resistance Army (led by Entertainment Editor fact that each bead, on every Invisible Children consists of schools, distribute scholarships, Joseph Kony) and the Ugandan necklace, is made of paper that student and adult volunteers give clean water supplies, med- government. Partnered with the Through the month of is then wrapped into a shape; do stretching across the United ical services, and much more, to Allied Democratic Forces, the December, a new club at Upper not be deceived by the construc- States and into the United the people of Uganda, especially LRA strives to overpower the St. Clair High School, Invisible tion of the necklaces because Kingdom (www.invisiblechil- the children (www.invisiblechil- government of Uganda headed Children, conducted a book after being painted, they are dren.com). In order to under- dren.com). by President Yoweri Museveni. drive in order to provide reading truly beautiful and worth pur- stand truly what is occurring in “These students endure limit- In addition to the numerous material for the neglected chil- chasing. All profits from the Uganda, the main organization less struggles on a daily basis - lives lost and thousands of dren in Uganda. -

AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL of TRADE MARKS 10 April 2008

Vol: 22 , No. 14 10 April 2008 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it at http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/epublish/content/olsEpublications.jsp or using the "Online Journals" link on the IP Australia home page. The Australian Official Journal of Designs is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 10 April 2008 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes ...................... 5366 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed ................ 5367 Registrations Linked ............................... 5364 Applications for Extension of Time ...................... 5366 Applications for Amendment .......................... 5366 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registration/Protection .......... 5089 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1228132 to 1228980 ............................. 5081 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed ...................................... 5368 Withdrawn..................................... 5370 Assignments,TransmittalsandTransfers.................. 5370 Cancellations of Entries in Register ...................... 5371 Notices........................................ 5366 Opposition Proceedings -

Arbiter, October 22 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 10-22-1997 Arbiter, October 22 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. 'I 1 WEDNESDAt OaOBER22,1997 ---, •••• _----- -~_. __ ._--_ • .,-- •• _- --- .-._--'~'-- .. - •• ~_ - •• > WEDNESDAY, OaOBER 22, 1997 by Eric Ellis 6U'(S ::r:tJGeO@) 1b"fi.lINj(F~ A . WHIt6J So 1: nt.C(OG'O "'-0 ~AK€ A Ro,4D- TRll'S:X-rniW6St: 1 ( •••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••.••••••• -".I!~~a.a.LIl.LL& .......-..JLLL&.LI~L&.LJ. educat.ion : I Top T~n reason's why Dirk 1 Kempthorne The { S({J)1UUrce should come for NEWS home and at become Idaho's BSU governor by Asencion Ramirez Opinion Editor 10. He's always·wanted to be the HSIC (Head Spud In Charge). 9. It's one way for the nation to stop associating him with Helen Chenoweth. (Hell,it's the reason voters sent her to Washington). 8. If he doesn't do it, Bruce Willis will. 7. "Kempthorne Kicks @$$" makes for a good slogan. 6. Spending four years in Boise seems a lot more fun than spending four more years in Washington with Larry Craig. 5. -

Filibuster 2014 Is Indeed a Labor of Love

A diverse collection of short narratives, poetry, photographs & illustrations, courtesy of the creative minds that a!end Auburn University at Montgomery CALLING ALL CREATIVE MINDS I HAVE TAKEN UPON MYSELF AN OCCUPATION FOR THE DELIGHT OF THE WORLD TORI BOYD AND FOR THE COMFORT OF NOBLE HEARTS Victoria Boyd, formerly Spencer, started her own magically perfect fairytale life March –GOTTFRIED VON STRASSBURG, TRISTAN 16, 2013. She will be graduating in May of 2014 with a degree in Secondary Education/ Language Arts. She has a life that is busy no ma"er how much she tries to slow it KATIE LINDGREN down. She has two small pups that are the Katie is a senior at AUM. She’s majoring in love of her life, aside from the husband. She Dear Readers, English Secondary Education with a minor has an obsessive fondness for antiques and in Theater. When she isn’t studying she turns into a stunt driver when she sees an My vision for this year’s publication was not only spends time cooking, sewing, or gardening. estate sale sign on the side of the road. She an outlet for the creative minds of AUM, but also Her favorite authors include Charlo"e crochets, decorates, bakes, and reads, all in a look into their identities, into the pieces that Bronte, Jane Austen, Lord Tennyson, excess because she has no internal gauge to come together to form a strong community of Harper Lee, and Kathryn Stocke". make her do things in moderation. educated minds. My commitment to this edition, as well as my overall goal, was to highlight the unique lives and passions of our writers and artists. -

Ink, a Literary Arts Magazine, Issue 13, Spring 2019

Ink A Literary Arts Magazine Issue 13 Woodland Community College Spring 2019 Editors: Gerrie “GiGi” Williams, Gurtaj Grewal, Holly Palandoken, Onica P. Roman, and Marcos Estrada Cover Art: Matthew Featherstone, Blood Moon and Eclipse Cover Poem: Henry Sevening, “A Distant Moonlit Forest” Printing: Mike Wieber, Yuba College Print Shop Faculty Advisor: Kevin Ferns, Professor of English, Woodland Community College Submissions If you are a current student of Woodland Community College, Colusa County Campus, or Lake County Campus and would like to contribute to future issues, please see ink.yccd.edu for submission guidelines and deadlines. Donations Your generous donation contributes to the cost of printing this publication. If you would like to help build a lasting legacy of the arts and literature at Woodland Community College, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the WCC Literary Progress Fund. Details are online at ink.yccd.edu. Ink, A Literary Arts Magazine is a trademark of Woodland Community College. All work is original and copyrighted by the contributor. The opinions expressed are those of the contributor and not those of the faculty, staff, or other contributors. Special thanks to the Woodland Community College Foundation, which provided the funding to print and distribute this 13th issue of Ink, A Literary Arts Magazine. This magazine would not be possible in its current form without the support of the Foundation. https://wcc.yccd.edu/foundation/ INK.YCCD.EDU Page 2 *Table of Contents Poems and Short Stories: Beach -

"ANOTHER YOU" the Debut Single from His Upcoming Solo Release, Son of a Preacher Man

THE INNOVATORS R &R Kicks Off 2009 With A Celebration THE SPIN: Beyoncé 'Rings' In Year Of People And With Biggest Urban Hit To Date Companies On ine ' n Innovating New PROFILE: Clear Channel's Technologies, Products, Guru Evai Harrison Programming, . TALENT: R &R Debuts New Weekly Revenue Sources, Column Devoted To Air Talent Distribution Platforms And RADIO st RECORDS PROMOTION: Surviving The More Dreaded Post -Holiday 'Dead Zoie' JANUARY 9, 2009 NC. 1796 $6.5C www.RàdioandReco-ds.com Multi- Platinum Artist 3 time ASCAP Songwriter of the Year Host of GONE COUNTRY 1, 2 & 3 One of People Magazine's Most Powerful People in the Music Industry Producer of the #1 Song of 2008 WB Nashville proudly presents "ANOTHER YOU" The debut single from his upcoming solo release, Son Of A Preacher Man www.americanradiohistory.com i TES ìsi Got i d i at agic 107.7 Orlando! Tesh is king of MID -DAY here at Magic We get lots of cDmments from listeners who enjoy his 'lntelligeice for yct r Life.' Even better, that advice triggers listener recall. i like that people think about ourstatien when gang about their daily routine, due to advice they heard Jahn give cw- the air. #1 P12+, #1 P18+, #1 W18+, #1 W25--54, #1P35-64, #1 W45-54* `pry -g 2CC8 Ken Payne Prograr- Diector Magic 137.7 WMGF -FM Clear Channel Radio - Orando IniIIigence our L1ïfe all your host John Tesh Over 300 Affiliates- Fiery dayirart & lormat VitWW.TESH.CONf Contact: Scott Meyers The TeshMedia Group 38E- 548 -8637 or 516-829 -0964 scotigrrEyers.net www.americanradiohistory.com WWW.RADIOANDRECORDS.COM: INDUSTRY AND FORMAT NEWS, AS IT HAPPENS, AROUND THE CLOCK. -

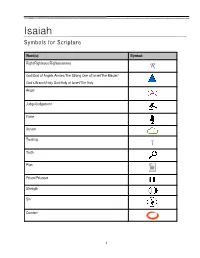

Isaiah Symbols for Scripture

Isaiah Symbols for Scripture Word(s): Symbol: Right/Righteous/Righteousness R God/God of Angels Armies/The Strong One of Israel/The Master/ God’s Branch/Holy God/Holy of Israel/The Holy Anger Judge/Judgement Fame Illusion Trusting T Truth Plan Prison/Prisoner Strength Sin Comfort 1 Isaiah Messages of Judgment Quit Your Worship Charades 1 The vision that Isaiah son of Amoz saw regarding Judah and Jerusalem during the times of the kings of Judah: Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah. 2–4 Heaven and earth, you’re the jury. Listen to GOD’s case: “I had children and raised them well, and they turned on me. The ox knows who’s boss, the mule knows the hand that feeds him, but not Israel. My people don’t know up from down. Shame! Misguided GOD-dropouts, staggering under their guilt-baggage, Gang of miscreants, band of vandals—My people have walked out on me, their GOD, turned their backs on The Holy of Israel, walked off and never looked back. 5–9 “Why bother even trying to do anything with you when you just keep to your bullheaded ways? You keep beating your heads against brick walls. Everything within you protests against you. From the bottom of your feet to the top of your head, nothing’s working right. Wounds and bruises and running sores— untended, unwashed, unbandaged. Your country is laid waste, your cities burned down. Your land is destroyed by outsiders while you watch, reduced to rubble by barbarians. Daughter Zion is deserted— like a tumbledown shack on a dead-end street, Like a tarpaper shanty on the wrong side of the tracks, like a sinking ship abandoned by the rats. -

DIRTY LITTLE SECRETS of the RECORD BUSINESS

DIRTY BUSINESS/MUSIC DIRTY $24.95 (CAN $33.95) “An accurate and well-researched exposé of the surreptitious, undisclosed, W hat happened to the record business? and covert activities of the music industry. Hank Bordowitz spares no It used to be wildly successful, selling LI one while exposing every aspect of the business.” LI outstanding music that showcased the T producer of Talking Heads, T performer’s creativity and individuality. TLE SE —Tony Bongiovi, TLE Aerosmith, and the Ramones Now it’s in rapid decline, and the best music lies buried under the swill. “This is the book that any one of us who once did time in the music SE business for more than fifteen minutes and are now out of the life wish This unprecedented book answers this CR we had written. We who lie awake at nights mentally washing our hands CR question with a detailed examination LITTLE of how the record business fouled its as assiduously yet with as much success as Lady Macbeth have a voice DIRTYLITTLE ET DIRTY in Hank Bordowitz. Now I have a big book that I can throw at the ET own livelihood—through shortsighted- S liars, the cheats, and the bastards who have fooled me twice.” S ness, stubbornness, power plays, sloth, and outright greed. Dirty Little Secrets o —Hugo Burnham, drummer for Gang of Four, o f of the Record Business takes you on a former manager and major-label A&R executive f the the hard-headed tour through the corridors ofof thethe of the major labels and rides the waves “Nobody should ever even think about signing any kind of music industry SECRSECRETSETS contract without reading this book. -

Calliope 2011

CALLIOPE The Student Journal of Art and Literature Volume VIII — Spring 2011 Poetry 1 Christine Camp Ode to Temptation First Prize 4 Jessica Redmiles An Alien 4 Gaisu Yari I Think It Is Fall First Prize, ESL 6 Ricardo J Erazo Twilight Anagke 17 Rahmien Rahim Amin The Beauty of a Butterfly Hon. Mention, ESL 17 Ponnia Achu Muyen The Weather is Cold Hon. Mention, ESL 17 Nafisa Abdulali A Mother with her Child Hon. Mention, ESL 18 Jacqui Barrineau Epilogue - Unfinished 19 Novpreet Bajwa The Saffron Veil 26 Nathan Moore Persephone Third Prize 28 Henry W. Leeker Fly Burial Second Prize 48 Andy Tran The Brevity of Night 50 Nader Ahmed Nothingness of Thin Air 67 CJ Ramones The Paprika Jungle 68 Nicholas Aronow The Setting Sun Creative Non-Fiction 8 Jinwoo Lee Grandfather’s Apartments Second Prize, ESL 10 Rebecca Tallant Just Ten Minutes First Prize 12 Lauren A. Kiefer Katrina Second Prize 19 Julie Taguding That’s Amore 27 Numita Yadav The Place That is Special to Me Third Prize, ESL 45 Elizabeth A. Fike Lost in Paris 49 Claudia Ayala Special Place Hon. Mention, ESL 54 Ngoc Phuong Bich Nguyen My Antique Mother 57 Nathan Moore The Music of Lizards Third Prize 60 Henry W. Leeker The Guise of Male Writers 63 Katherine Ayesha Raheem Walking in the Spiderwebs Fiction 2 Novpreet Bajwa A Proposal to Remember First Prize 7 Andrew O’Donnell Silence Third Prize 20 Katherine Ayesha Raheem Charming’s Tragedy Second Prize 38 Katrina Nicole Hawkins See No Evil 41 Nader Ahmed Demagoguery in the Time of Religion i Art Ryan Piersante Self portrait Cover Prize 8 -

Copyright by Esther Díaz Martín 2018

Copyright by Esther Díaz Martín 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Esther Díaz Martín certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radiophonic Feminisms: The Sounds and Voices of Contemporary Latina Radio Hosts in the U.S. Southwest, 1990-2017 Committee: Héctor Domínguez Ruvalcaba, Supervisor Luis Cárcamo-Huechante Kelly McDonough Julie A. Minich Radiophonic Feminisms: The Sounds and Voices of Contemporary Latina Radio Hosts in the U.S. Southwest, 1990-2017 by Esther Díaz Martín Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Dedication Para todas aquellas que les gusta el güiri güiri, empezando por mi mamá. Acknowledgements Foremost, I would like to thank the staff, faculty, and colegas in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese who have provided me with the resources, guidance, and space of convivencia that allowed me to evolve as a scholar and complete this present work. I thank my advisor Héctor Domínguez Ruvalcaba for hearing my voice and for helping me to tune- in to the broader conversations on the topics of gender, sex, and body politics. I am deeply grateful for the feedback, encouragement, and enthusiasm of my dissertation committee, Luis Cárcamo-Huechante, Kelly McDonough, and Julie A. Minich. I wish to acknowledge the Center for Mexican American Studies and the Inter- University Program for Latino Studies for providing me with the resources I needed to finish the last stretch of my program through the IUPRL-Mellon Dissertation Fellowship.