Lest We Forget: Free-Thought and the Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leftist Case for War in Iraq •fi William Shawcross, Allies

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 27, Issue 6 2003 Article 6 Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard Abstract Shawcross is superbly equipped to assess the impact of rogue States and terrorist organizations on global security. He is also well placed to comment on the risks of preemptive invasion for existing alliances and the future prospects for the international rule of law. An analysis of the ways in which the international community has “confronted evil,” Shawcross’ brief polemic argues that U.S. President George Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair were right to go to war without UN clearance, and that the hypocrisy of Jacques Chirac was largely responsible for the collapse of international consensus over the war. His curious identification with Bush and his neoconservative allies as the most qualified to implement this humanitarian agenda, however, fails to recognize essential differences between the leftist case for war and the hard-line justification for regime change in Iraq. BOOK REVIEW VENGEANCE AND EMPIRE: THE LEFTIST CASE FOR WAR IN IRAQ WILLIAM SHAWCROSS, ALLIES: THE U.S., BRITAIN, EUROPE, AND THE WAR IN IRAQ* Hal Blanchard** INTRODUCTION In early 2002, as the war in Afghanistan came to an end and a new interim government took power in Kabul,1 Vice President Richard Cheney was discussing with President George W. -

Christianity, Islam & Atheism

Christianity, Islam & Atheism Reflections on Religion, Society & Politics Michael Cooke 2 Christianity, Islam & Atheism About the author Michael Colin Cooke is a retired public servant and trade union activist who has a lifelong interest in South Asian history, politics and culture. He has served as an election monitor in Sri Lanka. Michael is the author of The Lionel Bopage Story: Rebellion, Repression and the Struggle for Justice in Sri Lanka (2011). He has also penned when the occasion demanded a number of articles and film reviews. He lives in Melbourne. Published 2014 ISBN 978-1-876646-15-8 Resistance Books: resistancebooks.com Contents 1.Genesis............................................................................................5 2.The Evolution of a Young Atheist .............................................13 India...................................................................................................................... 13 Living in the ’70s down under.............................................................................. 16 Religious fundamentalism rears its head............................................................. 20 3.Christianity: An Atheist’s Homily ................................................21 Introduction – the paradox that is Christianity................................................... 21 The argument....................................................................................................... 23 It ain’t necessarily so: Part 1................................................................................ -

Is God Great?

IS GOD GREAT? CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS AND THE NEW ATHEISM DEBATE Master’s Thesis in North American Studies Leiden University By Tayra Algera S1272667 March 14, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Second reader: Ms. N.A. Bloemendal MA 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1 – The New Atheism Debate and the Four Horsemen .............................................. 17 Chapter 2 – Christopher Hitchens ............................................................................................ 27 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................. 433 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................... 455 2 3 Introduction “God did not make us, we made God” Christopher Hitchens (2007) "What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence" Christopher Hitchens (2003) “Religion is violent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism and tribalism and bigotry, invested in ignorance and hostile to free inquiry, contemptuous of women and coercive toward children." Christopher Hitchens (2007) These bold statements describe the late Christopher Hitchens’s views on religion in fewer than 50 words. He was a man of many words, most aimed at denouncing the role of religion in current-day societies. Religion is a concept that is hard -

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

The Left and the Algerian Catastrophe

THE LEFT AND THE ALGERIAN CATASTROPHE H UGH R OBERTS n explaining their sharply opposed positions following the attacks on the IWorld Trade Center and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001, two promi- nent writers on the American Left, Christopher Hitchens and Noam Chomsky, both found it convenient to refer to the Algerian case. Since, for Hitchens, the attacks had been the work of an Islamic fundamentalism that was a kind of fascism, he naturally saw the Algerian drama in similar terms: Civil society in Algeria is barely breathing after the fundamentalist assault …We let the Algerians fight the Islamic-fascist wave without saying a word or lending a hand.1 This comment was probably music to the ears of the Algerian government, which had moved promptly to get on board the US-led ‘coalition’ against terror, as Chomsky noted in articulating his very different view of things: Algeria, which is one of the most murderous states in the world, would love to have US support for its torture and massacres of people in Algeria.2 This reading of the current situation was later supplemented by an account of its genesis: The Algerian government is in office because it blocked the democratic election in which it would have lost to mainly Islamic-based groups. That set off the current fighting.3 The significance of these remarks is that they testify to the fact that the Western Left has not addressed the Algerian drama properly, so that Hitchens and Chomsky, neither of whom pretend to specialist knowledge of the country, have THE LEFT AND THE ALGERIAN CATASTROPHE 153 not had available to them a fund of reliable analysis on which they might draw. -

Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science

Printer Friendly Version - Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science http://richarddawkins.net/article,1090,Unbelievable-Thats-what-religion-is-says-Christopher- Hitchens-in-his-profoundly-skeptical-manifesto,Daniel-C-Dennett-The-Boston-Globe Tuesday, May 15, 2007 | Reason : Commentary Print this article with comments | Without comments Unbelievable: That's what religion is, says Christopher Hitchens in his profoundly skeptical manifesto by Daniel C. Dennett, The Boston Globe Thanks to Florian Widder for the link. Reposted from: http://www.boston.com/ae/books/articles/2007/05/13/unbelievable/ Unbelievable: That's what religion is, says Christopher Hitchens in his profoundly skeptical manifesto God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything By Christopher Hitchens Twelve, 307 pp., $24.99 In earlier ages reliable information was rather hard to get, and in general people could be excused for taking the founding myths of their religions on faith. These were the "facts" that "everyone knew," and anybody who had a skeptical itch could check it out with the local priest or rabbi or imam, or other religious authority. Today, there is really no excuse for such ignorance. It may not be your fault if you don't know the facts about the history and tenets of your own religion, but it is somebody's fault. Or more charitably, perhaps we have all been victimized by an accumulation of tradition that http://richarddawkins.net/print.php?id=1090 (1 of 3) [11/26/2007 10:21:03 AM] Printer Friendly Version - Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science strongly enjoins us to lapse into a polite lack of curiosity about these facts, for fear of causing offense. -

U Ottawa L'universite Canadienne Canada's University FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES 1^=1 FACULTY of GRADUATE and ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES

nm u Ottawa L'Universite canadienne Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES 1^=1 FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Universitc canadienne Canada's university Steven Tomlins M.A. (Religious Studies) _._„„__„„„._ Department of Religious Studies In Science we Trust: Dissecting the Chimera of New Atheism TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS Lori Beaman Peter Beyer Anne Vallely Gary W. Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies IN SCIENCE WE TRUST: DISSECTING THE CHIMERA OF NEW ATHEISM Steven Tomlins Student Number: 5345726 Degree sought: Master of Arts, Religious Studies University of Ottawa Thesis Director: Lori G. Beaman © Steven Tomlins, Ottawa, Canada, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-73876-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-73876-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciaies ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Rethinking of the Moral and Political Ideas of Socrates in Contemporary Scenario- an Analysis

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 1 January 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 RETHINKING OF THE MORAL AND POLITICAL IDEAS OF SOCRATES IN CONTEMPORARY SCENARIO- AN ANALYSIS DIVAKARA. T.S Research Scholar Department of Studies in Philosophy Manasagangothri, University of Mysore Mysuru, Karnataka-570006. ABSTRACT: Socrates was a classical Greek Philosopher credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy and as being the first moral philosopher, of the western ethical tradition of thought An enigmatic figure, he made no writings, and is known chiefly through the accounts of classical writers. writing after his lifetime, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon. Other sources include the contemporaneous Antisthenes Arstippus, and Aeschines of Sphettos.Aristophanes , a Playwrite is the only source to have written during his lifetime Plato’s dialogues are among the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity, though it is unclear the degree to which Socrates himself is "hidden behind his 'best disciple'.Through his portrayal in Plato's dialogues, Socrates has become renowned for his contribution to the field of ethics , and it is this Platonic Socrates who lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic method, or elenchus.The elenchus remains a commonly used tool in a wide range of discussions, and is a type of pedagogy in which a series of questions is asked not only to draw individual answers, but also to encourage fundamental insight into the issue at hand. Plato's Socrates also made important and lasting contributions to the field of epistemology , and his ideologies and approach have proven a strong foundation for much Western philosophy that has followed. -

A Pragmatic Ethics of Belief (Draft – Presented at the Nordic Pragmatism Network Workshop “Pragmatism and the Ethics of Belief, Jyväskylä, Finland, December 2008)

Ulf Zackariasson Jyväskylä 15-17/12 2008 Ethics and a Pragmatic Ethics of Belief (Draft – presented at the Nordic Pragmatism Network workshop “Pragmatism and the Ethics of Belief, Jyväskylä, Finland, December 2008) Ulf Zackariasson University of Adger Introduction Outside the world of philosophy journals and conferences, there can be little doubt that moral considerations comprise the most potent source of critique of religious practices. Nevertheless, within philosophy of religion, moral critique has played a remarkably modest role, and the Anglo-American mainstream of philosophy of religion has a rather awkward attitude towards moral critique, since its focus is almost exclusively on epistemic justification. I think this awkwardness stems from a conception of religious practices which construes them as logically prior to moral reflection on these practices. Pragmatism, as I understand it, offers a more adequate articulation of the relation between ethics and religion, where religious practices are understood as responses to problematic situations that, to a significant extent, have moral implications. Hence, moral critique – I use moral and ethical as synonyms here – does not come into play only after these practices are formed; they are – or may be – important elements of the process through which they are constituted. In order to bring out the difference this makes for philosophical reflection on religion, and why a reconstruction is called for, I will compare a currently prominent attempt to justify belief, William Alston’s, to a -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

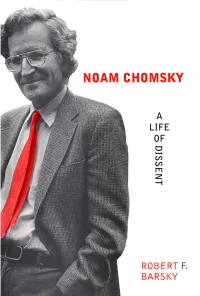

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky Addressing a Crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky addressing a crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989. Noam Chomsky A Life of Dissent Robert F. Barsky ECW PRESS Copyright © ECW PRESS, 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process—electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW PRESS. CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Barsky, Robert F. (Robert Franklin), 1961- Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55022-282-1 (bound) ISBN 1-55022-281-3 (pbk.) 1. Chomsky, Noam. 2. Linguists—United States—Biography. I. Title. P85.C47B371996 410'.92 C96-930295-9 This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and with the assistance of grants provided by the Ontario Arts Council and The Canada Council. Distributed in Canada by General Distribution Services, 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Ontario M3B 2T6. Distributed in the United States and internationally by The MIT Press. Photographs: Cover (1989), frontispiece (1989), and illustrations 18, 24, 25 (1989), © Elaine Briere; illustration 1 (1992), © Donna Coveney, is used by per- mission of Donna Coveney; illustrations 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20,21,22,23,26, © Necessary Illusions, are used by permission of Mark Achbar and Jeremy Allaire; illustrations 5, 8, 9, 10 (1995), © Robert F. -

New Atheism and the Scientistic Turn in the Atheism Movement MASSIMO PIGLIUCCI

bs_bs_banner MIDWEST STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY Midwest Studies In Philosophy, XXXVII (2013) New Atheism and the Scientistic Turn in the Atheism Movement MASSIMO PIGLIUCCI I The so-called “New Atheism” is a relatively well-defined, very recent, still unfold- ing cultural phenomenon with import for public understanding of both science and philosophy.Arguably, the opening salvo of the New Atheists was The End of Faith by Sam Harris, published in 2004, followed in rapid succession by a number of other titles penned by Harris himself, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Victor Stenger, and Christopher Hitchens.1 After this initial burst, which was triggered (according to Harris himself) by the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, a number of other authors have been associated with the New Atheism, even though their contributions sometimes were in the form of newspapers and magazine articles or blog posts, perhaps most prominent among them evolutionary biologists and bloggers Jerry Coyne and P.Z. Myers. Still others have published and continue to publish books on atheism, some of which have had reasonable success, probably because of the interest generated by the first wave. This second wave, however, often includes authors that explicitly 1. Sam Harris, The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason (New York: W.W. Norton, 2004); Sam Harris, Letter to a Christian Nation (New York: Vintage, 2006); Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006); Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (New York: Viking Press, 2006); Victor J. Stenger, God:The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist (Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2007); Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (New York: Twelve Books, 2007).