Background Information Study Tour Ethiopia 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Red Terror NEVER AGAIN

Praise for books by Nobel Peace Prize finalist R. J. Rummel "26th in a Random House poll on the best nonfiction book of the 20th Century" Random House (Modern Library) “. the most important . in the history of international relations.” John Norton Moore Professor of Law and Director, Center for National Security Law, former Chairman of the Board of Directors of the U. S. Institute of Peace “. among the most exciting . in years.” Jim Powell “. most comprehensive . I have ever encountered . illuminating . .” Storm Russell “One more home run . .” Bruce Russett, Professor of International Relations “. has profoundly affected my political and social views.” Lurner B Williams “. truly brilliant . ought to be mandatory reading.” Robert F. Turner, Professor of Law, former President of U.S. Institute of Peace ". highly recommend . ." Cutting Edge “We all walk a little taller by climbing on the shoulders of Rummel’s work.” Irving Louis Horowitz, Professor Of Sociology. ". everyone in leadership should read and understand . ." DivinePrinciple.com “. .exciting . pushes aside all the theories, propaganda, and wishful thinking . .” www.alphane.com “. world's foremost authority on the phenomenon of ‘democide.’” American Opinion Publishing “. excellent . .” Brian Carnell “. bound to be become a standard work . .” James Lee Ray, Professor of Political Science “. major intellectual accomplishment . .will be cited far into the next century” Jack Vincent, Professor of Political Science.” “. most important . required reading . .” thewizardofuz (Amazon.com) “. valuable perspective . .” R.W. Rasband “ . offers a desperately needed perspective . .” Andrew Johnstone “. eloquent . very important . .” Doug Vaughn “. should be required reading . .shocking and sobering . .” Sugi Sorensen NEVER AGAIN Book 4 Red Terror NEVER AGAIN R.J. -

Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia

Friedrich zur Heide Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia BfN-Skripten 317 2012 Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia Friedrich zur Heide Cover pictures: Tributary of the Blue Nile River near the Nile falls (top left); fisher in his traditional Papyrus boat (Tanqua) at the southwestern papyrus belt of Lake Tana (top centre); flooded shores of Deq Island (top right); wild coffee on Zege Peninsula (bottom left); field with Guizotia scabra in the Chimba wetland (bottom centre) and Nymphaea nouchali var. caerulea (bottom right) (F. zur Heide). Author’s address: Friedrich zur Heide Michael Succow Foundation Ellernholzstrasse 1/3 D-17489 Greifswald, Germany Phone: +49 3834 83 542-15 Fax: +49 3834 83 542-22 Email: [email protected] Co-authors/support: Dr. Lutz Fähser Michael Succow Foundation Renée Moreaux Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Christian Sefrin Department of Geography, University of Bonn Maxi Springsguth Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Fanny Mundt Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Scientific Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Michael Succow Michael Succow Foundation Email: [email protected] Technical Supervisor at BfN: Florian Carius Division I 2.3 “International Nature Conservation” Email: [email protected] The study was conducted by the Michael Succow Foundation (MSF) in cooperation with the Amhara National Regional State Bureau of Culture, Tourism and Parks Development (BoCTPD) and supported by the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) with funds from the Environmental Research Plan (FKZ: 3510 82 3900) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). -

Background Information Study Tour Ethiopia 2007

Landscape Transformation and Sustainable Development in Ethiopia | downloaded: 13.3.2017 Background information for a study tour through Ethiopia, 4-20 September 2006 University of Bern Institute of Geography https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.71076 2007 source: Cover photographs Left: Digging an irrigation channel near Lake Maybar to substitute missing rain in the drought of 1984/1985. Hans Hurni, 1985. Centre: View of the Simen Mountains from the lowlands in the Simen Mountains National Park. Gudrun Schwilch, 1994. Right: Extreme soil degradation in the Andit Tid area, a research site of the Soil Conservation Research Programme (SCRP). Hans Hurni, 1983. Landscape Transformation and Sustainable Development in Ethiopia Background information for a study tour through Ethiopia, 4-20 September 2006 University of Bern Institute of Geography 2007 3 Impressum © 2007 University of Bern, Institute of Geography, Centre for Development and Environment Concept: Hans Hurni Coordination and layout: Brigitte Portner Contributors: Alemayehu Assefa, Amare Bantider, Berhan Asmamew, Manuela Born, Antonia Eisenhut, Veronika Elgart, Elias Fekade, Franziska Grossenbacher, Christine Hauert, Karl Herweg, Hans Hurni, Kaspar Hurni, Daniel Loppacher, Sylvia Lörcher, Eva Ludi, Melese Tesfaye, Andreas Obrecht, Brigitte Portner, Eduardo Ronc, Lorenz Roten, Michael Rüegsegger, Stefan Salzmann, Solomon Hishe, Ivo Strahm, Andres Strebel, Gianreto Stuppani, Tadele Amare, Tewodros Assefa, Stefan Zingg. Citation: Hurni, H., Amare Bantider, Herweg, K., Portner, B. and H. Veit (eds.). 2007. Landscape Transformation ansd Sustainable Development in Ethiopia. Background information for a study tour through Ethiopia, 4-20 September 2006, compiled by the participants. Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern, Bern, 321 pp. Available from: www.cde.unibe.ch. -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published Online: 14 Apr 2013

This article was downloaded by: [US Naval Academy] On: 25 June 2013, At: 06:09 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of the Middle East and Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujme20 The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published online: 14 Apr 2013. To cite this article: Nikolaos Biziouras (2013): The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961), The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 4:1, 21-46 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2013.771419 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

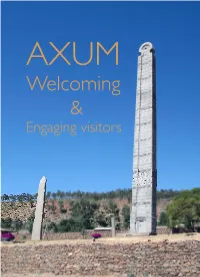

AXUM – Welcoming and Engaging Visitors – Design Report

Pedro Guedes (2010) AXUM – Welcoming and engaging visitors – Design report CONTENTS: Design report 1 Appendix – A 25 Further thoughts on Interpretation Centres Appendix – B 27 Axum signage and paving Presented to Tigray Government and tourism commission officials and stakeholders in Axum in November 2009. NATURE OF SUBMISSION: Design Research This Design report records a creative design approach together with the development of original ideas resulting in an integrated proposal for presenting Axum’s rich tangible and intangible heritage to visitors to this important World Heritage Town. This innovative proposal seeks to use local resources and skills to create a distinct and memorable experience for visitors to Axum. It relies on engaging members of the local community to manage and ‘own’ the various ‘attractions’ for visitors, hopefully keeping a substantial proportion of earnings from tourism in the local community. The proposal combines attitudes to Design with fresh approaches to curatorship that can be applied to other sites. In this study, propositions are tested in several schemes relating to the design of ‘Interpretation centres’ and ideas for exhibits that would bring them to life and engage visitors. ABSTRACT: Axum, in the highlands of Ethiopia was the centre of an important trading empire, controlling the Red Sea and channeling exotic African merchandise into markets of the East and West. In the fourth century (AD), it became one of the first states to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Axum became the major religious centre for the Ethiopian Coptic Church. Axum’s most spectacular archaeological remains are the large carved monoliths – stelae that are concentrated in the Stelae Park opposite the Cathedral precinct. -

Analysis of Politics in the Land Tenure System: Experience of Successive Ethiopian Regimes Since 1930

Vol. 10(8), pp. 111-118, September 2016 DOI: 10.5897/AJPSIR2016.0919 Article Number: 33FDAF560466 African Journal of Political Science and ISSN 1996-0832 Copyright © 2016 International Relations Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPSIR Full Length Research Paper Analysis of politics in the land tenure system: Experience of successive Ethiopian regimes since 1930 Teshome Chala College of Law and Governance, Department of Civics and Ethical Studies, Mekelle University, Ethiopia. Received 6 July, 2016; Accepted 1 September, 2016 This paper reviews the politics of land tenure in the last three regimes in Ethiopia, the Imperial, Derg and the incumbent government. It critically examines the nature and mechanisms of land alienation and related controversial issues carried out in the context of Ethiopian history by national actors. Ethiopian regimes have experienced a strong political debate on the appropriate land tenure policy. Imperial regime encouraged complex tenure system characterized by extreme state intervention. However, Derg effectively abolished previous feudal land owning system thereby distribute access to land through Peasant Associations. The incumbent government on the other hand changed certain the policies of former regime by declaring state land ownership in the Federal Constitution. The debate continued yet again with privatization -vs- state ownership dichotomy. The key source of controversy is emanated from how Ethiopian regimes have used land resource as an instrument to realize sustainable development. Therefore, the nature of those contentions would be analyzed by taking into account private and government ownership system from theoretical perspective in need of policy option in this subject. Key words: Land tenure system, state land ownership, Derg, Ethiopian People Revolution Democratic Front (EPRDF). -

History of Events and Internal Developement. the Example of The

Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies University of Addis Ababa, 1984 Edited by Dr Taddese Beyene Volume 1 isbn — Volume 1: 1 85450 000 7 Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa 1988 Table of Contents Preface Opening Address The New Ethiopia: Major Defining Characteristics. Research Trends in Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University over the last Twenty-Five Years. Prehistory and Archaeology Early Stone Age Cultures in Ethiopia. Alemseged Abbay Les Monuments Gondariens des XVIIe et XVIIIe Steeles. Une Vue d'ensemble. Francis Anfray Le Gisement Paleolithique de Melka-Kunture. Evolution et Culture. Jean Chavaillon A Review of the Archaeological Evidence for the Origins of Food Production in Ethiopia. John Desmond Clark Reflections on the Origins of the Ethiopian Civilization. Ephraim Isaac and Cain Felder Remarks on the Late Prehistory and Early History of Northern Ethiopia. Rodolfo Fattovich History to 1800 Is Näwa Bäg'u an Ethiopian Cross? Ewa Balicka-Witakowska The Ruins of Mertola-Maryam. Stephen Bell Who Wrote "The History of King Sarsa Dengel" - Was it the Monk Bahrey? S. B. Chernetsov Les Affluents de la Rive Droite du Nil dans la Geographie Antique. Jehan Desanges Ethiopian Attitudes towards Europeans until 1750. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski The Ta'ämra 'Iyasus: a study of textual and source-critical problems. S. Gem The Mediterranean Context for the Medieval Rock-Cut Churches of Ethiopia. Michael Gerven Introducing an Arabic Hagiography from Wällo Hussein Ahmed Some Hebrew Sources on the Beta-Israel (Falasha). Steven Kaplan The Problem of the Formation of the Peasant Class in Ethiopia. Yu. M. Kobischanov The Sor'ata Gabr - a Mirror View of Daily Life at the Ethiopian Royal Court in the Middle Ages. -

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region The situation of child marriage in Qewet and Bahir Dar Zurida: a focus on gender roles, parenting and young people’s future perspectives Abeje Berhanu Dereje Tesama Beleyne Worku Almaz Mekonnen Lisa Juanola Anke van der Kwaak University of Addis Ababa & Royal Tropical Institute January 2019 1 Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background of the Yes I Do programme .............................................................................................. 4 1.2 Process of identifying themes for this study ....................................................................................... 4 1.3 Social and gender norms related to child marrige .............................................................................. 5 1.4 Objective of the study ......................................................................................................................... 7 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Description of the study areas ............................................................................................................. 9 2.1.1 Qewet woreda, North Shewa zone..............................................................................................