United Nations Human Settlements Programme Un-Habitat Sud-Net Cities in Climate Change Initiative (Ccci)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Save the Date PE: Edward Kaddumukasa 2015-2016

“The Rotary Wheel” THE ROTARY CLUB OF KAMPALA - CLUB NO. 17287 Theme 2014- 2015 “Light Up Rotary” Magazine Month Vol. 4 Issue 39, 23rd April, 2015 Since May 20th 1957, District 9211, R.I Zone 20A RCKLA Rotary Club of Kampala Web: www.rotarykampala.org President’s Message ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ tor Angel Kisekka and our Club Administrative Assistant April is Winne Nansubuga for always ensuring that the maga- Magazine zine is printed and distributed on time every week. Spe- M o n t h , cial thanks also go to some of those who over this year a time to have contributed articles such as Rtns. Tinka, Phionah, celebrate Diana, Sheila, Musolini, Gabriel, Aidah, Ayebare, and a the global whole host of others. n e t w o r k of Rotary’s Nonetheless, I still call upon all of you to write and en- o f f i c i a l rich our bulletin with your Rotary experiences and work. magazines, We need more hands to add to the contents of the which pro- magazine in a bid to know get to know ourselves bet- vide valuable information to 1.2 ter professionally, as well as exchange vocational/ pro- million Rotarians. There is the dan- fessional experiences. ger that we turn, magazines into a ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ school of inattention: people look without seeing and read without The District Conference is just around the corner; let comprehension. us go in large numbers to Dar-es-Salaam, to network with other Rotarians, and support our incoming District Our own Namuziga has been Governor, DGE Robert Waggwa Nsibirwa. -

Out and About December 6.Indd

THE BEAT, Friday, December 6, 2013 37 Kololo Dormans, Yusuf Lule Road, Garden City Cee Cee’s Restaurant & Coffee Bar, Royal Ternan Avenue Nakasero Cayenne Restaurant & Lounge, Kira Road, Bukoto Shopping Mall Palms Arcade, Butabika, Luzira Soho Café & Grill, Course View Towers, Centenary Barbeque Lounge, Jinja Road, Centenary Park Bean Café, Ggaba Road, Kansanga Coffee at Last, Unit H1, Mobutu Road, Yusuf Lule Road Chi Bar & Restaurant, 56 Lumumba Avenue, Nakasero Crocodile Café & Bar, Cooper Road, Makindye The Lounge, 38 Buganda Road, Nakasero Equator Bar, Sheraton Hotel, Ternan Avenue, Nakasero Kisementi Café Kawa Muyenga, Tankhill Road, Brood, Cargen House Food Court, Fat Boyz, 7 Cooper Road Kisementi Endiro Coffee, 23B Cooper Road, Muyenga Kampala Road Faze 2, 10 Nakasero Road, Nakasero Kisementi New Day Coffee, Metroplex Shopping Mall, Le Patisserie, 12721 Ggaba Road, Nsambya Gatto Matto, 3 Bandali Rise, Bugolobi The Bistro, 15 Cooper Road, Kisementi Naalya Iguana, 8 Bukoto Street, Kamwokya Prunes, 8 Wampewo Avenue Kololo Café Ballet, 34c Kyadondo Road, Nakasero Check us out on Facebook The Beat Uganda Jakob’s Lounge, Second Level, Pearl Guest House, Muyenga Rocks & Roses Tea Room, 2 Acacia Avenue Park Square Café, Sheraton Kampala Hotel, and on Twitter @THEBEATUg Jazzville, Bandali Rise, Bugolobi Johnny Biz, Opposite Makindye Country Club Makindye Just Kicking Sports Bar, Cooper Road, Kisementi Kasalina’s, 4 Speke Road, Kampala Kawa Lounge, The Hub, Oasis Mall, Yusuf Lule Road La Fiesta Bar, Blue Island, Lakeside Adventure Park Lion -

UNIPH Epidemiological Bulletin

MINISTRY OF HEALTH UGANDA Epidemiological Bulletin UNIPH Volume 1| Issue 2 | Dec 2016 Quarterly Epidemiological Bulletin of the Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Ministry of Health October—December 2016 EDITORIAL TEAM Dr Monica Musenero | Dear Reader, ACHS , Epidemiology & Surveillance Division, MoH Welcome to the 5th edition, Issue 2 Volume 1 of the Uganda Dr Immaculate Nabukenya | National Institute Public Health (UNIPH) Quarterly Epidemio- logical Bulletin. ACHS, Veterinary Public Health, MoH This bulletin aims to inform the district, national, and global Dr Alex Riolexus Ario | stakeholders on the public health interventions, evaluation of Field Coordinator, Uganda Public Health Fellowship surveillance systems and outbreak investigations undertaken in Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, disease prevention and control by Ministry of Health. MoH In this issue, we present highlights on evaluation of surveillance system in emergence setting, chemical poisoning due to con- Ms Leocadia Kwagonza | sumption of a dead pig, chemical poisoning in a flower farm and PHFP-FET, Fellow, Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI) Typhoid misdiagnosis among others. These studies generated evidence and results which will be used to inform planning and Ms Joy Kusiima interventions in the country and beyond. PHFP-FET Fellow, Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI) For any further information regarding the articles, feel free to Ms Claire Birabawa contact us at: [email protected] OR lkwagon- [email protected] PHFP-FET Fellow, Division of Health Information, We will appreciate any feedback regarding the content and gen- MoH eral outlook of this issue and look forward to hearing from you. Dr Phoebe Hilda Alitubeera We hope this will be both an informative and enjoyable reading for you. -

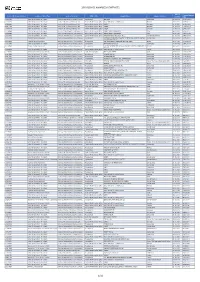

2019 Service Awarded Contracts

2019 SERVICE AWARDED CONTRACTS Date of Contract Amount Contract Reference Number Service Contract Type Service Category WHO Office Supplier Name Supplier Country Contract USD Signature 202232143 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Infrastructure, security, licences. Headquarters IMPLENIA Switzerland 25-03-2019 58,083,257.26 202183409 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office Name witheld for security Reason Pakistan 29-01-2019 6,425,830.31 202223251 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 14-03-2019 5,745,805.50 202301092 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 17-06-2019 5,745,805.50 202373109 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 11-09-2019 5,745,805.50 202257659 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Medical Supplies and equipment. Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 25-04-2019 5,400,000.00 202468261 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Medical Supplies and equipment. Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 11-12-2019 4,552,870.80 202353466 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Implementation of programmes. Eastern Mediterranean Office INTERNATIONAL SOS (GULF) W.L.L United Arab Emirates 21-08-2019 3,946,850.00 202101014 Technical Service Agreement Services.Implementation of programmes. Headquarters NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL United States 26-11-2019 3,177,292.00 AND PREVENTION, INC. 202083588 Technical Service Agreement Services.Implementation of programmes. Headquarters KINTAMPO HEALTH RESEARCH CENTRE (KHRC) Ghana 20-11-2019 3,065,901.00 202210446 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Infrastructure, security, licences. -

Tdb 34Th Agm of Board of Governors 29Th July to 01St

29TH JULYTDB TO 34 01THST AGMAUGUST OF BOARD 2018, SERENA OF GOVERNORS HOTEL KAMPALA The Government of Uganda is hosting the 34th Annual General Meeting of TDB’s Board of Governors from the 29th of July to the 1st of August 2018, at the KAMPALA SERENA HOTEL, Uganda. In collaboration with the Ministry of Finance of Uganda, measures have been put in place to assist each Minister or representative delegate. Accomodation has been booked for the delegates by TDB. TDB has negotiated special rates. Alternative hotel recommendations and practical information are provided in this kit. PROTOCOL AND LOGISTICS - Geraldine Kaligirwa [email protected] - Mahider Kebede [email protected] - Judith Mongala [email protected] INFORMATION KIT 29th July - 1st August 2018, KAMPALA SERENA HOTEL, UGANDA TDB 34TH AGM OF BOARD OF GOVERNORS VISA TRANSPORT Delegates’ visas will be granted on -Return shuttle is available from arrival. Submit a valid scanned copy the airport to hotel, provided by of your passport biodata page to the Governement of Uganda. [email protected] Submit your flight details no Immigration officers will request later than 23rd of July, 2018 to the following upon arrival: [email protected] -A valid return or onward ticket - Hotel shuttle service is available with -Confirmed accommodation additional charge of USD 50.00 (one -Yellow fever vaccination card way) per person. Book 4 days prior to check-in at the respective hotel. -Airport taxis are also available for personal errands. SECURITY CALL The Government of Uganda will make - Local time : GMT +3 appropriate security arrangements for - Country code: +256 participants at the selected hotels and - Intern. -

List of Authorised Facilities As of 30/1/2019

LIST OF AUTHORISED FACILITIES AS OF 30/1/2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Atomic Energy Council is a body corporate established by the Atomic Energy Act (AEA), 2008, Act No.24, Cap.143 Laws of Uganda to regulate the peaceful applications of ionising radiation, to provide for the protection and safety of individuals, society and the environment from the dangers resulting from ionising radiation. Section 32 (1) of Atomic Energy Act No. 24 of 2008 requires facilities with practices involving ionizing radiation not to acquire, own, possess, operate, import, export, hire, loan, receive, use, install, commission, decommission, transport, store, sell, distribute, dispose of, transfer, modify, upgrade, process, manufacture or undertake any practice related to the application of atomic energy unless permitted by an authorization from Atomic Energy Council. # Facility Name Type of status District Licensed Machine/ License Number Date of Date of Facility radioactive sources Issue Expiry 1. Abii Clinic Medical Private Kampala Dental X-ray (OPG) AEC/PU/1409 11/04/2017 10/04/2019 Fixed X-ray AEC/PU/1090/02 25/01/2018 24/01/2020 Fixed Dental X-ray AEC/PU/1265/01 30/4/2018 29/4/2020 2. Abubaker Technical Services and Industrial Private Mukono 1 Nuclear gauge AEC/PU/1323/01 04/10/2018 03/10/2020 General Supplies Limited 3. Adjumani General Hospital Medical Government Adjumani Fixed X-ray AEC/PU/1515 17/11/2017 16/11/2019 4. AFYA Medical & Diagnostic Centre Medical Private Kasese AEC/PU/1024/03 18/12/2018 17/12/2020 5. Agakhan University Hospital-Acacia Medical Private Kampala Fixed Dental X-ray AEC/PU/1229/01 23/01/2018 22/01/2020 Medical Centre Fixed X-ray AEC/PU/1134/02 10/10/2018 09/10/2020 6. -

89952254.Pdf

2 Vol.1, ISSUE 9 - Apr. 2012 Vol.1, ISSUE 9 - Apr. 2012 3 HOTEL TRIANGLE Email: [email protected] 16 Buganda Road, Website: www.bougainviller.com Tel: 041-4231747 UGANDA HOTEL OWNERS ASSOCIATION Website: www.hoteltriangle.co.ug Hotel Africana Conference Complex HOTEL RUCH Tel: +256 (0)414 345 601 Kintu road, Fax: +256 (0)414 232 675 Mob: 078-2820100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] METROPLE HOTEL KAMPALA HUMURA RESORT 51/53 Windsor crescent, 3 Kitante Close, Kololo, Tel: 0414391000 Tel: 0414 700 400 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] MUNYONYO COMMONWEALTH RESORT LTD IMPERIAL ROYALE HOTEL Tel: 041-4227111 7 Kintu Road, Email: [email protected] Tel: 041-7111001 Email: [email protected] PROTEA HOTEL KAMPALA Website: www.imperialhotels.co.ug 8 Upper Kololo Terrace, Tel: 031-2550000, IVY’S HOTEL Email: [email protected] 90/91 wakaliaga Road, Tel: 041-4273664 RWIZI ARCH HOTEL Email: [email protected] Mob: 0772 684 839 Email: [email protected] KABIRA COUNTRY CLUB 63 Old Kira Road, Bukoto SERENA LAKE VICTORIA RESORT Tel: 031-2227222/3/4/5 Lweza-Kigo Road Off Entebbe Road Email: kabiracountryclub@kabiracountry- Tel: (+256) 417121000, club.com SHANGRI-IA HOTEL LTD KAMPALA REGENCY HOTEL Tel: 041-4250366, 78/79 Namirembe Road 041-4236213, Tel: 041-427018, Email: [email protected] Mob: 077-2444921 SHERATON KAMPALA HOTEL KAMPALA SERENA HOTEL 1Ternan Avenue, Nakasero Kintu Road, Nakasero Tel: 041-4420000, Tel: 041-4309000, 031-2322460 031-2309000 Mob: 075-2780010 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] SPEKE HOTEL 1996 LTD LE BOUGAINVILLER HOTEL Nile Avenue, Tel: 041-4259221 Ext.2009 Opp. -

Letter from the Executive Director

Beyond wildlife... a community experience!! July - December 2011 Letter from the Inside this issue Letter from the Executive Executive Director Director Uganda Named the Top Tourist It is my great pleasure to welcome you in-directly linked to the tourism industry, Destination for 2012 all to the inaugural issue of the bi-annual conservation agencies, government VSPT - Kyambura Gorge Women’s Coffee Cooperative Pearls of Uganda Post. Uganda Community agencies, local and international tour Project Tourism Association (UCOTA) produced operators, media houses, training Let us Embrace our Pearl this newsletter with support from institutions, embassies, supermarkets, USAID-Sustainable Tourism in the community tourism enterprises and UCOTA CTE Awards 2011 UCOTA Annual General Meeting Albertine Rift (STAR), in partnership more. It can also be found on the UCOTA 2011 with Uganda Tourism Board (UTB), website (www.ucota.or.ug), the Pearls of Funding Opportunities Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) and Uganda website (www.pearlsofuganda. Tourism Needs to Adopt the Association of Uganda Tour Operators org) and the USAID-STAR website Social Media Tools (AUTO). (www.star-uganda.org). Public Private Tourism Partnerships bring Turkish Travel In this publication, sustainable tourism Sustainable tourism is tourism attempting Channel to Uganda articles are solicited from all stakeholders to make a low negative impact on the Operationalising the 2008 for publishing in order to embrace environment and local culture, while Uganda Tourism Act economic development through tourism helping to generate employment for local $1 For the Future Campaign in our nation. The Post also allows for people. The aim of sustainable tourism space for advertisements therefore is to ensure that development brings a travel, rapid technology advances and integrating all sectors. -

Uganda Section 2020

PRESIDENT OF UGANDA UGANDA UGANDA SECTION 2020 EDITION PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA H.E. YOWERI KAGUTA MUSEVENI East African Manufacturers & Investors Directory East African Manufacturers & Investors Directory 129 UGANDA PROFILE UGANDA UGANDA Uganda Profile ganda officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the southwest Uby Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. Uganda is the world’s second most populous landlocked country after Ethiopia. The southern part of the country includes a substantial portion of Lake Victoria, shared with Kenya and Tanzania. Uganda is in the African Great Lakes region. Uganda also lies within the Nile basin, and has a varied but generally a modified equatorial type of climate. Uganda takes its name from the Buganda kingdom, which encompasses a large portion of the south of the country, including the capital Kampala. The people of Uganda were hunter-gatherers until 1,700 to 2,300 years ago, when Bantu- speaking populations migrated to the southern parts of the country. Environment and conservation The Crested crane is the national bird. Conservation in Uganda Uganda has 60 protected areas, including ten national parks: Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and Rwenzori Mountains National Park (both UNESCO World Heritage Sites[43]), Kibale National Park, Kidepo Valley National Park, Lake Mburo National Park, Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, Mount Elgon National Park, Murchison Falls National Park, Queen Elizabeth National Park, and Semuliki National Park. Economy and infrastructure The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling. -

Dr Margaret Mungherera by Dr Chukwuma C. Oraegbunam

Dr Chukwuma C. Oraegbunam Nigerian Medical Association (NMA) BACKGROUND • Born on 25th October, 1957 to Seezi and Joyce Mungherera. • Her father, a retired civil servant, traced his roots to the Butaleja District in the Eastern Region of Uganda. • She attended Primary, secondary and tertiary education in Uganda. • Graduated from to Makerere University Medical School in 1982 education. • Obtained Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 1984 from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. • Obtained Master of Medicine degree in psychiatry from Makerere University in 1992. • Her clinical and research interest was in forensic psychiatry. WORK • 1992 – 2000: Resident Doctor at the Butabika National Referral Hospital • 2000 – 2003: Consultant Psychiatrist at the Mulago National Referral Hospital • 2003 – 2012: Senior Consultant psychiatrist at the Mulago Hospital Complex • 2012 – 2015: Clinical head, Directorate of Medical Services (Departments of Internal Medicine and Psychiatry) at the Mulago National Referral Hospital. • Retired 30th June, 2015. SERVICES • President, Ugandan Medical Association for six terms. • October 2013 – October 2014: President, World Medical Association. First female President of the WMA from Africa. • October 2016 – death: Chairperson of the International Association of Medical Regulatory Authorities. • She was also a founding member of Uganda Women Medical Doctors Association. CONTRIBUTIONS • As President of the Ugandan Medical Association, she midwifed the formation of regulatory bodies in East Africa region alongside colleagues from Kenya and Tanzania aimed at improving the standards of regulation of doctors and dental surgeons in the East African region. • This further led to a harmonized approach to Continuing Professional Development, a single harmonized curriculum for the training of undergraduate doctors and dental surgeons and another for training interns in 5 countries in the East African region (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi). -

Statistical Abstract for Kampala City 2019

Kampala City Statistical Abstract, 2019 STATISTICAL ABSTRACT FOR KAMPALA CITY 2019 Report prepared with support from Uganda Bureau of Statistics Kampala City Statistical Abstract, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS …………………………………………………………………….…………………………………………. vii ABOUT THIS STATISTICAL ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………...………. viii ACKNOWLEDGMENT ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… ix DEFINITIONS USED AS ADAPTED FROM THE NATIONAL POPULATION & HOUSING CENSUS REPORT (2014) 1 CHAPTER ONE: KAMPALA BACKGROUND INFORMATION …………………….…………………………. 2 CHAPTER TWO: CITY ADMINISTRATION ………………………………………….……………………………. 10 CHAPTER THREE: DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS ………….……………. 23 CHAPTER FOUR: CITY ECOMOMY, BUSINESS, EMPLOYMENT AND LABOUR SERVICES ……………. 30 CHAPTER FIVE: TRANSPORT AND GETTING AROUND KAMPALA ……………….………………………. 51 CHAPTER SIX: HEALTH SERVICES …………………………………….……………………………………. 61 CHAPTER SEVEN: WATER, SANITATION, ENVIRONMENT ……………………………………………………. 73 CHAPTER EIGHT: EDUCATION SERVICES …………………………………….………………………………. 81 CHAPTER NINE: SOCIAL SERVICES ……………………………………….……………………………………. 87 CHAPTER TEN: CRIME, ACCIDENTS AND FIRE EMERGECIES ………………….……………………….. 93 CHAPTER ELEVEN: ASSORTED KCCA PERFORMANCE STATISTICS 2011 – 2019 …….…………………. 97 GENERAL INFORMATION …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Kampala City Statistical Abstract, 2019 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Distance to Kampala from Major Cities ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Guide Du Delegue

GUIDE DU DELEGUE Préparé par le Comité national d’organisation de la COP9 de l’Ouganda 9e Session de la Conférence des Parties à la Convention sur les zones humides (Ramsar, Iran, 1971) Kampala, Ouganda 8-15 novembre 2005 « Les zones humides et l'eau: richesse pour la vie, richesse pour en vivre » Logo de la COP9 Le logo de la COP9 qui apparaît sur chaque page de ce manuel montre quelqu’un en train de récolter des ressources dans une zone humide. On y trouve les symboles suivants: les rides à la surface de l’eau pour la durabilité, le bleu pour l’eau, et le jaune pour le soleil et la chaleur de l’Afrique. Les bandes bleues représentent la nature mondiale de cet événement. TABLE DES MATIÈRES Messages de bienvenue................................... Remerciements.................................... Informations sur la COP9……………………… Informations générales ………… Kampala en bref ………………………… Les zones humides d’Ouganda...................................... Une chaleureuse bienvenue en Ouganda et à la COP9 Le Gouvernement ougandais a le privilège d’accueillir la 9e Conférence des Parties à la Convention de Ramsar (COP9). C’est un honneur particulier pour l'Ouganda car c’est la première fois que cette Conférence se réunit sur le sol africain. Au nom du Gouvernement et du peuple ougandais, je souhaite chaleureusement la bienvenue aux délégués et au personnel de conférence venus du monde entier, en espérant que chacun saura apprécier son séjour ici. Outre l'ordre du jour important de la Conférence, je voudrais saisir cette occasion pour vous inviter à connaître l’autre face de l'Ouganda. Prenez le temps de découvrir nos paysages superbes, notre riche culture et l'hospitalité traditionnelle des Ougandais.