UNIPH Epidemiological Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline Documenting the Experiences of East African Deployed Experts Who Volunteered to Fight Ebola in West Africa Implemented By

Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline Documenting the experiences of East African deployed experts who volunteered to fight Ebola in West Africa Implemented by: Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline Documenting the experiences of East African deployed experts who volunteered to fight Ebola in West Africa Contents Introduction . 6 Foreword from the Hon . Jesca Eriyo . 9 Foreword from Dr Zabulon Yoti . .. 10 Foreword from Dr Jackson Amone . 12 Foreword from Dr Irene Lukassowitz . 13 George Acire . 14 Rebecca Racheal Apolot . 17 Sarah Awilo . 22 Dr Mwaniki Collins . 24 Charles Draleku . 26 Emmanuel Ejoku .. 28 Dr Madina Hussein . 31 Loveness Daniel Isojick . 34 Dr Abdulrahman Said Kassim . 36 Teddy Kusemererwa . .. 40 Liliane Luwaga . 43 Dr Appolinaire Manirafasha . 46 Dr Landry Mayigane . 48 James Mugume . 50 Dr Monica Musenero . 52 Doreen Nabawanuka . 55 Dr Bella Nihorimbere . 56 Teresia Wairimu Thuku . 57 Tony Walter Onena . 59 Acknowledgements . 61 4 Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline 5 Introduction ccording to the World Health Organization (WHO), Others, seeing scenes of death and devastation on their The East African Community Secretariat, in collaboration the Ebola epidemic that occurred in West Africa television screens, just felt compelled to do whatever they with the Federal Government of Germany through the Abetween 2014 and 2016 killed over 11,000 people could to help . Given that so many West African health GIZ-coordinated Support to Pandemic Preparedness in out of the almost 30,000 that were infected . From one -

One Health Workforce Project

One Health Workforce Project John Deen One Health Workforce Project Part of USAID’s EPT2 Program Emerging Threats Program Emerging Threats Program Each civil society needs the capacity and confidence to defend itself Emerging Threats Program Invasion by pathogens • Significant death and morbidity • Large amount of disruption – Health system – Economy – Agriculture – Trade – Politics • Large influx of aid is also disruptive • A breakdown in civil society Emerging Threats Program Factors for Human Disease Emergence . 1415 species of infectious agents reported to cause disease in humans . Viruses, prions, bacteria, rickettsia, fungi, protozoa, helminths . 868/1415 (61%) zoonotic . 175 emerging infectious diseases . 132/175 (75%) emerging zoonoses Taylor et al. Risk factors for disease emergence. 2001, Philosophical Transactions, The Royal Society, London Emerging Threats Program Human Cases One Health – Public health Wild Animal Domestic Animal as part of a larger “ecosystem” Animal Amplification C A Wildlife Surveillance/ S Forecasting Early Detection Control E Opportunity S Human Amplification TIME Which predicts a country’s susceptibility to a pathogen? Agent or Host? Emerging Threats Program Eg Ebola • The presence of the agent (R0 <2) • The presence of a host defense (Workforce plus government capacity) Emerging Threats Program National One Health Workforce • Competent • Inspired • Empowered To • Prevent • Detect • Respond Emerging Threats Program History • SARS IHR aim of 100% of countries compliant • Ebola, MERS IHR at 32%, PVS lower -

Lessons for the Future

Lessons for the Future What East African experts learned from fighting the Ebola epidemic in West Africa A regional conference with international participation held in Nairobi, Kenya from 6th to 8th November 2017 Lessons for the Future What East African experts learned from fighting the Ebola epidemic in West Africa A regional conference with international participation held in Nairobi, Kenya from 6th to 8th November 2017 Conference Report Implemented by: Contents List of Abbreviations . 5 Foreword . 7 Summary . 8 Introduction . 9 East joins West in the fight against Ebola . 10 A wealth of experience . 11 Objectives of the conference . 11 Conference methodology and brief programme overview . 12 Voices from the Ebola frontline: Documenting a treasure trove of experience . 12 Day one: Welcoming delegates to Kenya . 16 Opening speech by Dr Monica Musenero . 17 Germany’s experiences of establishing a database of rapidly deployable experts . 19 First sharing of experiences . 20 Exploring eight themes . 20 The first four pre-set themes . 21 The four themes subsequently chosen by the participants . 21 Theme 1: Being ready at short notice – establishing a pool of deployable experts . 22 What worked well? . 22 What did not work well? . 22 Lessons learned . 24 Recommendations . .. 24 Theme 2: Taking informed decisions – effective communication to mitigate risks and crises . 25 What worked well? . 25 What did not work well? . 25 Lessons learned . 27 Recommendations . .. 28 Theme 3: Working together - One Health . .28 What worked well? . 28 What did not work well? . 29 Lessons learned . 29 Recommendations . .. 30 Theme 4: Effective logistics – what, where, when and how? . 31 What worked well? . -

Save the Date PE: Edward Kaddumukasa 2015-2016

“The Rotary Wheel” THE ROTARY CLUB OF KAMPALA - CLUB NO. 17287 Theme 2014- 2015 “Light Up Rotary” Magazine Month Vol. 4 Issue 39, 23rd April, 2015 Since May 20th 1957, District 9211, R.I Zone 20A RCKLA Rotary Club of Kampala Web: www.rotarykampala.org President’s Message ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ tor Angel Kisekka and our Club Administrative Assistant April is Winne Nansubuga for always ensuring that the maga- Magazine zine is printed and distributed on time every week. Spe- M o n t h , cial thanks also go to some of those who over this year a time to have contributed articles such as Rtns. Tinka, Phionah, celebrate Diana, Sheila, Musolini, Gabriel, Aidah, Ayebare, and a the global whole host of others. n e t w o r k of Rotary’s Nonetheless, I still call upon all of you to write and en- o f f i c i a l rich our bulletin with your Rotary experiences and work. magazines, We need more hands to add to the contents of the which pro- magazine in a bid to know get to know ourselves bet- vide valuable information to 1.2 ter professionally, as well as exchange vocational/ pro- million Rotarians. There is the dan- fessional experiences. ger that we turn, magazines into a ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ school of inattention: people look without seeing and read without The District Conference is just around the corner; let comprehension. us go in large numbers to Dar-es-Salaam, to network with other Rotarians, and support our incoming District Our own Namuziga has been Governor, DGE Robert Waggwa Nsibirwa. -

Out and About December 6.Indd

THE BEAT, Friday, December 6, 2013 37 Kololo Dormans, Yusuf Lule Road, Garden City Cee Cee’s Restaurant & Coffee Bar, Royal Ternan Avenue Nakasero Cayenne Restaurant & Lounge, Kira Road, Bukoto Shopping Mall Palms Arcade, Butabika, Luzira Soho Café & Grill, Course View Towers, Centenary Barbeque Lounge, Jinja Road, Centenary Park Bean Café, Ggaba Road, Kansanga Coffee at Last, Unit H1, Mobutu Road, Yusuf Lule Road Chi Bar & Restaurant, 56 Lumumba Avenue, Nakasero Crocodile Café & Bar, Cooper Road, Makindye The Lounge, 38 Buganda Road, Nakasero Equator Bar, Sheraton Hotel, Ternan Avenue, Nakasero Kisementi Café Kawa Muyenga, Tankhill Road, Brood, Cargen House Food Court, Fat Boyz, 7 Cooper Road Kisementi Endiro Coffee, 23B Cooper Road, Muyenga Kampala Road Faze 2, 10 Nakasero Road, Nakasero Kisementi New Day Coffee, Metroplex Shopping Mall, Le Patisserie, 12721 Ggaba Road, Nsambya Gatto Matto, 3 Bandali Rise, Bugolobi The Bistro, 15 Cooper Road, Kisementi Naalya Iguana, 8 Bukoto Street, Kamwokya Prunes, 8 Wampewo Avenue Kololo Café Ballet, 34c Kyadondo Road, Nakasero Check us out on Facebook The Beat Uganda Jakob’s Lounge, Second Level, Pearl Guest House, Muyenga Rocks & Roses Tea Room, 2 Acacia Avenue Park Square Café, Sheraton Kampala Hotel, and on Twitter @THEBEATUg Jazzville, Bandali Rise, Bugolobi Johnny Biz, Opposite Makindye Country Club Makindye Just Kicking Sports Bar, Cooper Road, Kisementi Kasalina’s, 4 Speke Road, Kampala Kawa Lounge, The Hub, Oasis Mall, Yusuf Lule Road La Fiesta Bar, Blue Island, Lakeside Adventure Park Lion -

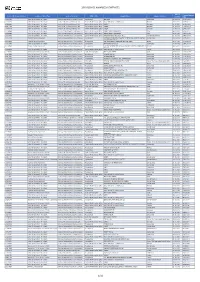

2019 Service Awarded Contracts

2019 SERVICE AWARDED CONTRACTS Date of Contract Amount Contract Reference Number Service Contract Type Service Category WHO Office Supplier Name Supplier Country Contract USD Signature 202232143 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Infrastructure, security, licences. Headquarters IMPLENIA Switzerland 25-03-2019 58,083,257.26 202183409 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office Name witheld for security Reason Pakistan 29-01-2019 6,425,830.31 202223251 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 14-03-2019 5,745,805.50 202301092 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 17-06-2019 5,745,805.50 202373109 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.HR (Internal, External), SSA. Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 11-09-2019 5,745,805.50 202257659 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Medical Supplies and equipment. Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 25-04-2019 5,400,000.00 202468261 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Medical Supplies and equipment. Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 11-12-2019 4,552,870.80 202353466 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Implementation of programmes. Eastern Mediterranean Office INTERNATIONAL SOS (GULF) W.L.L United Arab Emirates 21-08-2019 3,946,850.00 202101014 Technical Service Agreement Services.Implementation of programmes. Headquarters NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL United States 26-11-2019 3,177,292.00 AND PREVENTION, INC. 202083588 Technical Service Agreement Services.Implementation of programmes. Headquarters KINTAMPO HEALTH RESEARCH CENTRE (KHRC) Ghana 20-11-2019 3,065,901.00 202210446 Letter Of Agreement - Non Grant Services.Infrastructure, security, licences. -

Tdb 34Th Agm of Board of Governors 29Th July to 01St

29TH JULYTDB TO 34 01THST AGMAUGUST OF BOARD 2018, SERENA OF GOVERNORS HOTEL KAMPALA The Government of Uganda is hosting the 34th Annual General Meeting of TDB’s Board of Governors from the 29th of July to the 1st of August 2018, at the KAMPALA SERENA HOTEL, Uganda. In collaboration with the Ministry of Finance of Uganda, measures have been put in place to assist each Minister or representative delegate. Accomodation has been booked for the delegates by TDB. TDB has negotiated special rates. Alternative hotel recommendations and practical information are provided in this kit. PROTOCOL AND LOGISTICS - Geraldine Kaligirwa [email protected] - Mahider Kebede [email protected] - Judith Mongala [email protected] INFORMATION KIT 29th July - 1st August 2018, KAMPALA SERENA HOTEL, UGANDA TDB 34TH AGM OF BOARD OF GOVERNORS VISA TRANSPORT Delegates’ visas will be granted on -Return shuttle is available from arrival. Submit a valid scanned copy the airport to hotel, provided by of your passport biodata page to the Governement of Uganda. [email protected] Submit your flight details no Immigration officers will request later than 23rd of July, 2018 to the following upon arrival: [email protected] -A valid return or onward ticket - Hotel shuttle service is available with -Confirmed accommodation additional charge of USD 50.00 (one -Yellow fever vaccination card way) per person. Book 4 days prior to check-in at the respective hotel. -Airport taxis are also available for personal errands. SECURITY CALL The Government of Uganda will make - Local time : GMT +3 appropriate security arrangements for - Country code: +256 participants at the selected hotels and - Intern. -

Quarantine Sierra Leone

QUARANTINE IN SIERRA LEONE Lessons Learned On the use of quarantine in Sierra Leone as a support measure during the Ebola Epidemic 2014-2015 Laura Sustersic for Welthungerhilfe Sierra Leone Freetown April 2015 TABLE of CONTENTS 1. INTRODICTION 3 1.1 THE CONTEXT: EBOLA EPIDEMICS IN HISTORY 4 2. BRIEF OVERVIEW OF OUTBREAK AND WHH ENGAGEMENT 5 3. PRINCIPLES AND USE OF QUARANTINE FOR EBOLA CONTAINMENT 6 3.1 PUBLIC HEALTH PRINCIPLES AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES 6 3.2 PRINCIPLES OF EBOLA CONTAINMENT 6 3.3 MONITORING OF CONTACTS 7 3.4 CHOOSING QUARANTINE IN SIERRA LEONE 8 4. IMPLEMENTING GOOD QUARANTINES IN SIERRA LEONE 10 4.1 HHQ, FLOW CHART WITH STAKEHOLDERS 11 4.2 ELEMENTS TO IMPLEMENT SUCCESSFUL HOUSEHOLDS QUARANTINE 12 4.2.1 CONTACT TRACING 12 4.2.2 RESPECTING BASIC HUMAN RIGHTS 12 4.2.3 RECOGNIZING ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF INDIVIDUALS IN QUARANTINE 13 4.2.4 COMMUNITY SUPPORT 13 4.2.5 SECURITY 13 4.3 PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH QUARANTINE 14 4.3.1 ISSUES WITH OTHER RESPONSE PILLARS 15 4.3.2 SHORTCOMINGS IN QUARANTINE SUPPORT SERVICES 15 4.3.4 ISSUES DIRECTLY RELATED TO QUARANTINE 16 4.3.5 ISSUES TO BE VERIFIED OR FURTHER DISCUSSED 16 4.4 SPECIAL CASE OF QUARANTINE IN SLUMS 16 5. LESSONS LEARNED 17 6. CONCLUSIONS 18 ANNEX 1-EBOLA OUTBREAK IN SIERRA LEONE 19 DERC District Ebola Response Centre EVD Ebola Virus Disease HH Households MoHS Min. of Health and Sanitation MSF Medicines Sans Frontières NERC National Ebola Response Centre NFI Non Food Items Q Quarantine SOP Standard Operating Procedures UNMEER UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response VIP Ventilated Improved Pit-latrines WA Western Area District WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene WHH Welthungerhilfe WHO World Health Organization 2 1. -

List of Authorised Facilities As of 30/1/2019

LIST OF AUTHORISED FACILITIES AS OF 30/1/2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Atomic Energy Council is a body corporate established by the Atomic Energy Act (AEA), 2008, Act No.24, Cap.143 Laws of Uganda to regulate the peaceful applications of ionising radiation, to provide for the protection and safety of individuals, society and the environment from the dangers resulting from ionising radiation. Section 32 (1) of Atomic Energy Act No. 24 of 2008 requires facilities with practices involving ionizing radiation not to acquire, own, possess, operate, import, export, hire, loan, receive, use, install, commission, decommission, transport, store, sell, distribute, dispose of, transfer, modify, upgrade, process, manufacture or undertake any practice related to the application of atomic energy unless permitted by an authorization from Atomic Energy Council. # Facility Name Type of status District Licensed Machine/ License Number Date of Date of Facility radioactive sources Issue Expiry 1. Abii Clinic Medical Private Kampala Dental X-ray (OPG) AEC/PU/1409 11/04/2017 10/04/2019 Fixed X-ray AEC/PU/1090/02 25/01/2018 24/01/2020 Fixed Dental X-ray AEC/PU/1265/01 30/4/2018 29/4/2020 2. Abubaker Technical Services and Industrial Private Mukono 1 Nuclear gauge AEC/PU/1323/01 04/10/2018 03/10/2020 General Supplies Limited 3. Adjumani General Hospital Medical Government Adjumani Fixed X-ray AEC/PU/1515 17/11/2017 16/11/2019 4. AFYA Medical & Diagnostic Centre Medical Private Kasese AEC/PU/1024/03 18/12/2018 17/12/2020 5. Agakhan University Hospital-Acacia Medical Private Kampala Fixed Dental X-ray AEC/PU/1229/01 23/01/2018 22/01/2020 Medical Centre Fixed X-ray AEC/PU/1134/02 10/10/2018 09/10/2020 6. -

Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Associated with Novel Virus Strain, Uganda, 2007–2008 Joseph F

Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Associated with Novel Virus Strain, Uganda, 2007–2008 Joseph F. Wamala, Luswa Lukwago, Mugagga Malimbo, Patrick Nguku, Zabulon Yoti, Monica Musenero, Jackson Amone, William Mbabazi, Miriam Nanyunja, Sam Zaramba, Alex Opio, Julius J. Lutwama, Ambrose O. Talisuna, and Sam I. Okware During August 2007–February 2008, the novel Bun- distinct species of Ebola virus were known: Zaire ebolavi- dibugyo ebolavirus species was identifi ed during an out- rus, Sudan ebolavirus, Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus, and Res- break of Ebola viral hemorrhagic fever in Bundibugyo ton ebolavirus. district, western Uganda. To characterize the outbreak as Although the reservoirs for the virus and mechanisms a requisite for determining response, we instituted a case- of transmission have not been fully elucidated, a recent series investigation. We identifi ed 192 suspected cases, of study reported that 4% of bats from Gabon were positive which 42 (22%) were laboratory positive for the novel spe- cies; 74 (38%) were probable, and 77 (40%) were negative. for Zaire Ebola virus immunoglobulin (Ig) G (3). Initial Laboratory confi rmation lagged behind outbreak verifi cation human infection presumably occurs when humans are ex- by 3 months. Bundibugyo ebolavirus was less fatal (case- posed to infected body fl uids of the animal reservoir or fatality rate 34%) than Ebola viruses that had caused pre- intermediate host. Thereafter, person-to-person transmis- vious outbreaks in the region, and most transmission was sion occurs through direct contact with body fl uids of an associated with handling of dead persons without appropri- infected person (1,2,4). After an incubation period of 1–21 ate protection (adjusted odds ratio 3.83, 95% confi dence days (1,2,5), an acute febrile illness develops in infected interval 1.78–8.23). -

89952254.Pdf

2 Vol.1, ISSUE 9 - Apr. 2012 Vol.1, ISSUE 9 - Apr. 2012 3 HOTEL TRIANGLE Email: [email protected] 16 Buganda Road, Website: www.bougainviller.com Tel: 041-4231747 UGANDA HOTEL OWNERS ASSOCIATION Website: www.hoteltriangle.co.ug Hotel Africana Conference Complex HOTEL RUCH Tel: +256 (0)414 345 601 Kintu road, Fax: +256 (0)414 232 675 Mob: 078-2820100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] METROPLE HOTEL KAMPALA HUMURA RESORT 51/53 Windsor crescent, 3 Kitante Close, Kololo, Tel: 0414391000 Tel: 0414 700 400 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] MUNYONYO COMMONWEALTH RESORT LTD IMPERIAL ROYALE HOTEL Tel: 041-4227111 7 Kintu Road, Email: [email protected] Tel: 041-7111001 Email: [email protected] PROTEA HOTEL KAMPALA Website: www.imperialhotels.co.ug 8 Upper Kololo Terrace, Tel: 031-2550000, IVY’S HOTEL Email: [email protected] 90/91 wakaliaga Road, Tel: 041-4273664 RWIZI ARCH HOTEL Email: [email protected] Mob: 0772 684 839 Email: [email protected] KABIRA COUNTRY CLUB 63 Old Kira Road, Bukoto SERENA LAKE VICTORIA RESORT Tel: 031-2227222/3/4/5 Lweza-Kigo Road Off Entebbe Road Email: kabiracountryclub@kabiracountry- Tel: (+256) 417121000, club.com SHANGRI-IA HOTEL LTD KAMPALA REGENCY HOTEL Tel: 041-4250366, 78/79 Namirembe Road 041-4236213, Tel: 041-427018, Email: [email protected] Mob: 077-2444921 SHERATON KAMPALA HOTEL KAMPALA SERENA HOTEL 1Ternan Avenue, Nakasero Kintu Road, Nakasero Tel: 041-4420000, Tel: 041-4309000, 031-2322460 031-2309000 Mob: 075-2780010 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] SPEKE HOTEL 1996 LTD LE BOUGAINVILLER HOTEL Nile Avenue, Tel: 041-4259221 Ext.2009 Opp. -

Letter from the Executive Director

Beyond wildlife... a community experience!! July - December 2011 Letter from the Inside this issue Letter from the Executive Executive Director Director Uganda Named the Top Tourist It is my great pleasure to welcome you in-directly linked to the tourism industry, Destination for 2012 all to the inaugural issue of the bi-annual conservation agencies, government VSPT - Kyambura Gorge Women’s Coffee Cooperative Pearls of Uganda Post. Uganda Community agencies, local and international tour Project Tourism Association (UCOTA) produced operators, media houses, training Let us Embrace our Pearl this newsletter with support from institutions, embassies, supermarkets, USAID-Sustainable Tourism in the community tourism enterprises and UCOTA CTE Awards 2011 UCOTA Annual General Meeting Albertine Rift (STAR), in partnership more. It can also be found on the UCOTA 2011 with Uganda Tourism Board (UTB), website (www.ucota.or.ug), the Pearls of Funding Opportunities Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) and Uganda website (www.pearlsofuganda. Tourism Needs to Adopt the Association of Uganda Tour Operators org) and the USAID-STAR website Social Media Tools (AUTO). (www.star-uganda.org). Public Private Tourism Partnerships bring Turkish Travel In this publication, sustainable tourism Sustainable tourism is tourism attempting Channel to Uganda articles are solicited from all stakeholders to make a low negative impact on the Operationalising the 2008 for publishing in order to embrace environment and local culture, while Uganda Tourism Act economic development through tourism helping to generate employment for local $1 For the Future Campaign in our nation. The Post also allows for people. The aim of sustainable tourism space for advertisements therefore is to ensure that development brings a travel, rapid technology advances and integrating all sectors.