Lessons for the Future – What East African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline Documenting the Experiences of East African Deployed Experts Who Volunteered to Fight Ebola in West Africa Implemented By

Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline Documenting the experiences of East African deployed experts who volunteered to fight Ebola in West Africa Implemented by: Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline Documenting the experiences of East African deployed experts who volunteered to fight Ebola in West Africa Contents Introduction . 6 Foreword from the Hon . Jesca Eriyo . 9 Foreword from Dr Zabulon Yoti . .. 10 Foreword from Dr Jackson Amone . 12 Foreword from Dr Irene Lukassowitz . 13 George Acire . 14 Rebecca Racheal Apolot . 17 Sarah Awilo . 22 Dr Mwaniki Collins . 24 Charles Draleku . 26 Emmanuel Ejoku .. 28 Dr Madina Hussein . 31 Loveness Daniel Isojick . 34 Dr Abdulrahman Said Kassim . 36 Teddy Kusemererwa . .. 40 Liliane Luwaga . 43 Dr Appolinaire Manirafasha . 46 Dr Landry Mayigane . 48 James Mugume . 50 Dr Monica Musenero . 52 Doreen Nabawanuka . 55 Dr Bella Nihorimbere . 56 Teresia Wairimu Thuku . 57 Tony Walter Onena . 59 Acknowledgements . 61 4 Fighting Ebola: Voices from the Frontline 5 Introduction ccording to the World Health Organization (WHO), Others, seeing scenes of death and devastation on their The East African Community Secretariat, in collaboration the Ebola epidemic that occurred in West Africa television screens, just felt compelled to do whatever they with the Federal Government of Germany through the Abetween 2014 and 2016 killed over 11,000 people could to help . Given that so many West African health GIZ-coordinated Support to Pandemic Preparedness in out of the almost 30,000 that were infected . From one -

One Health Workforce Project

One Health Workforce Project John Deen One Health Workforce Project Part of USAID’s EPT2 Program Emerging Threats Program Emerging Threats Program Each civil society needs the capacity and confidence to defend itself Emerging Threats Program Invasion by pathogens • Significant death and morbidity • Large amount of disruption – Health system – Economy – Agriculture – Trade – Politics • Large influx of aid is also disruptive • A breakdown in civil society Emerging Threats Program Factors for Human Disease Emergence . 1415 species of infectious agents reported to cause disease in humans . Viruses, prions, bacteria, rickettsia, fungi, protozoa, helminths . 868/1415 (61%) zoonotic . 175 emerging infectious diseases . 132/175 (75%) emerging zoonoses Taylor et al. Risk factors for disease emergence. 2001, Philosophical Transactions, The Royal Society, London Emerging Threats Program Human Cases One Health – Public health Wild Animal Domestic Animal as part of a larger “ecosystem” Animal Amplification C A Wildlife Surveillance/ S Forecasting Early Detection Control E Opportunity S Human Amplification TIME Which predicts a country’s susceptibility to a pathogen? Agent or Host? Emerging Threats Program Eg Ebola • The presence of the agent (R0 <2) • The presence of a host defense (Workforce plus government capacity) Emerging Threats Program National One Health Workforce • Competent • Inspired • Empowered To • Prevent • Detect • Respond Emerging Threats Program History • SARS IHR aim of 100% of countries compliant • Ebola, MERS IHR at 32%, PVS lower -

Lessons for the Future

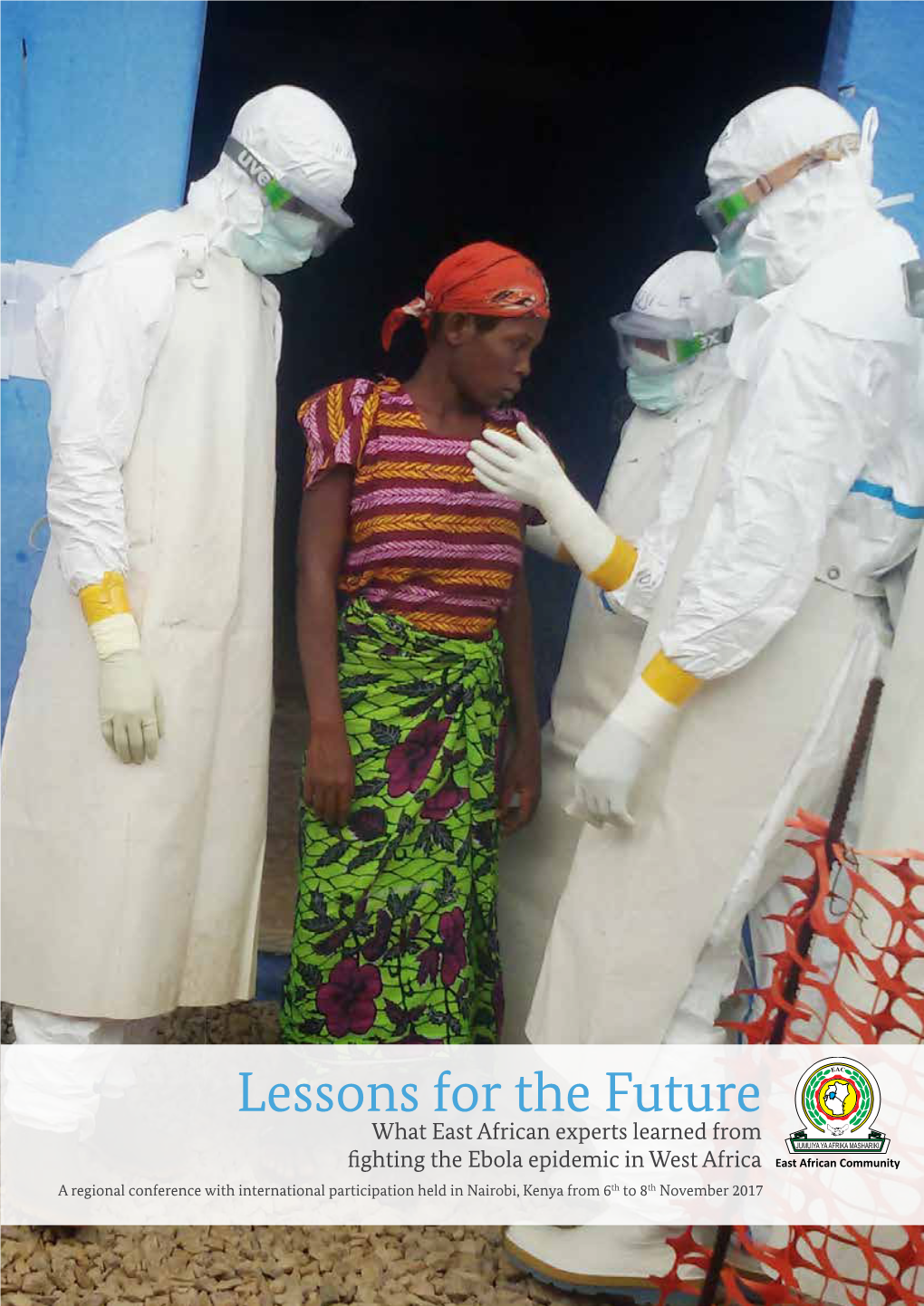

Lessons for the Future What East African experts learned from fighting the Ebola epidemic in West Africa A regional conference with international participation held in Nairobi, Kenya from 6th to 8th November 2017 Lessons for the Future What East African experts learned from fighting the Ebola epidemic in West Africa A regional conference with international participation held in Nairobi, Kenya from 6th to 8th November 2017 Conference Report Implemented by: Contents List of Abbreviations . 5 Foreword . 7 Summary . 8 Introduction . 9 East joins West in the fight against Ebola . 10 A wealth of experience . 11 Objectives of the conference . 11 Conference methodology and brief programme overview . 12 Voices from the Ebola frontline: Documenting a treasure trove of experience . 12 Day one: Welcoming delegates to Kenya . 16 Opening speech by Dr Monica Musenero . 17 Germany’s experiences of establishing a database of rapidly deployable experts . 19 First sharing of experiences . 20 Exploring eight themes . 20 The first four pre-set themes . 21 The four themes subsequently chosen by the participants . 21 Theme 1: Being ready at short notice – establishing a pool of deployable experts . 22 What worked well? . 22 What did not work well? . 22 Lessons learned . 24 Recommendations . .. 24 Theme 2: Taking informed decisions – effective communication to mitigate risks and crises . 25 What worked well? . 25 What did not work well? . 25 Lessons learned . 27 Recommendations . .. 28 Theme 3: Working together - One Health . .28 What worked well? . 28 What did not work well? . 29 Lessons learned . 29 Recommendations . .. 30 Theme 4: Effective logistics – what, where, when and how? . 31 What worked well? . -

UNIPH Epidemiological Bulletin

MINISTRY OF HEALTH UGANDA Epidemiological Bulletin UNIPH Volume 1| Issue 2 | Dec 2016 Quarterly Epidemiological Bulletin of the Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Ministry of Health October—December 2016 EDITORIAL TEAM Dr Monica Musenero | Dear Reader, ACHS , Epidemiology & Surveillance Division, MoH Welcome to the 5th edition, Issue 2 Volume 1 of the Uganda Dr Immaculate Nabukenya | National Institute Public Health (UNIPH) Quarterly Epidemio- logical Bulletin. ACHS, Veterinary Public Health, MoH This bulletin aims to inform the district, national, and global Dr Alex Riolexus Ario | stakeholders on the public health interventions, evaluation of Field Coordinator, Uganda Public Health Fellowship surveillance systems and outbreak investigations undertaken in Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, disease prevention and control by Ministry of Health. MoH In this issue, we present highlights on evaluation of surveillance system in emergence setting, chemical poisoning due to con- Ms Leocadia Kwagonza | sumption of a dead pig, chemical poisoning in a flower farm and PHFP-FET, Fellow, Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI) Typhoid misdiagnosis among others. These studies generated evidence and results which will be used to inform planning and Ms Joy Kusiima interventions in the country and beyond. PHFP-FET Fellow, Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI) For any further information regarding the articles, feel free to Ms Claire Birabawa contact us at: [email protected] OR lkwagon- [email protected] PHFP-FET Fellow, Division of Health Information, We will appreciate any feedback regarding the content and gen- MoH eral outlook of this issue and look forward to hearing from you. Dr Phoebe Hilda Alitubeera We hope this will be both an informative and enjoyable reading for you. -

Quarantine Sierra Leone

QUARANTINE IN SIERRA LEONE Lessons Learned On the use of quarantine in Sierra Leone as a support measure during the Ebola Epidemic 2014-2015 Laura Sustersic for Welthungerhilfe Sierra Leone Freetown April 2015 TABLE of CONTENTS 1. INTRODICTION 3 1.1 THE CONTEXT: EBOLA EPIDEMICS IN HISTORY 4 2. BRIEF OVERVIEW OF OUTBREAK AND WHH ENGAGEMENT 5 3. PRINCIPLES AND USE OF QUARANTINE FOR EBOLA CONTAINMENT 6 3.1 PUBLIC HEALTH PRINCIPLES AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES 6 3.2 PRINCIPLES OF EBOLA CONTAINMENT 6 3.3 MONITORING OF CONTACTS 7 3.4 CHOOSING QUARANTINE IN SIERRA LEONE 8 4. IMPLEMENTING GOOD QUARANTINES IN SIERRA LEONE 10 4.1 HHQ, FLOW CHART WITH STAKEHOLDERS 11 4.2 ELEMENTS TO IMPLEMENT SUCCESSFUL HOUSEHOLDS QUARANTINE 12 4.2.1 CONTACT TRACING 12 4.2.2 RESPECTING BASIC HUMAN RIGHTS 12 4.2.3 RECOGNIZING ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF INDIVIDUALS IN QUARANTINE 13 4.2.4 COMMUNITY SUPPORT 13 4.2.5 SECURITY 13 4.3 PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH QUARANTINE 14 4.3.1 ISSUES WITH OTHER RESPONSE PILLARS 15 4.3.2 SHORTCOMINGS IN QUARANTINE SUPPORT SERVICES 15 4.3.4 ISSUES DIRECTLY RELATED TO QUARANTINE 16 4.3.5 ISSUES TO BE VERIFIED OR FURTHER DISCUSSED 16 4.4 SPECIAL CASE OF QUARANTINE IN SLUMS 16 5. LESSONS LEARNED 17 6. CONCLUSIONS 18 ANNEX 1-EBOLA OUTBREAK IN SIERRA LEONE 19 DERC District Ebola Response Centre EVD Ebola Virus Disease HH Households MoHS Min. of Health and Sanitation MSF Medicines Sans Frontières NERC National Ebola Response Centre NFI Non Food Items Q Quarantine SOP Standard Operating Procedures UNMEER UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response VIP Ventilated Improved Pit-latrines WA Western Area District WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene WHH Welthungerhilfe WHO World Health Organization 2 1. -

Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Associated with Novel Virus Strain, Uganda, 2007–2008 Joseph F

Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Associated with Novel Virus Strain, Uganda, 2007–2008 Joseph F. Wamala, Luswa Lukwago, Mugagga Malimbo, Patrick Nguku, Zabulon Yoti, Monica Musenero, Jackson Amone, William Mbabazi, Miriam Nanyunja, Sam Zaramba, Alex Opio, Julius J. Lutwama, Ambrose O. Talisuna, and Sam I. Okware During August 2007–February 2008, the novel Bun- distinct species of Ebola virus were known: Zaire ebolavi- dibugyo ebolavirus species was identifi ed during an out- rus, Sudan ebolavirus, Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus, and Res- break of Ebola viral hemorrhagic fever in Bundibugyo ton ebolavirus. district, western Uganda. To characterize the outbreak as Although the reservoirs for the virus and mechanisms a requisite for determining response, we instituted a case- of transmission have not been fully elucidated, a recent series investigation. We identifi ed 192 suspected cases, of study reported that 4% of bats from Gabon were positive which 42 (22%) were laboratory positive for the novel spe- cies; 74 (38%) were probable, and 77 (40%) were negative. for Zaire Ebola virus immunoglobulin (Ig) G (3). Initial Laboratory confi rmation lagged behind outbreak verifi cation human infection presumably occurs when humans are ex- by 3 months. Bundibugyo ebolavirus was less fatal (case- posed to infected body fl uids of the animal reservoir or fatality rate 34%) than Ebola viruses that had caused pre- intermediate host. Thereafter, person-to-person transmis- vious outbreaks in the region, and most transmission was sion occurs through direct contact with body fl uids of an associated with handling of dead persons without appropri- infected person (1,2,4). After an incubation period of 1–21 ate protection (adjusted odds ratio 3.83, 95% confi dence days (1,2,5), an acute febrile illness develops in infected interval 1.78–8.23). -

Partnerships in a Time of COVID-19 Learning Paper

VIRTUAL CONFERENCE PARTNERSHIPS IN A TIME OF COVID-19 #COVIDPARTNERSHIPS CONFERENCE REFLECTIONS “The way forward is solidarity: solidarity at the national level and solidarity at the global level.” - Dr Tedros Abhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General, World Health Organization, April 2020. These words from Dr Tedros on the 13th April were an inspiration. Three days earlier, THET had launched our Lives on the Line: Health Worker Action Fund, channeling funds to support the physical and mental wellbeing of health workers on the frontline of the response to COVID-19 in Africa and parts of Asia. This was the least we could do, in recognition of the extensive and long-standing ties of professional friendship between health workers in the UK and their peers overseas. The UK has been gravely affected by COVID-19, but as we learnt from our partners across the Health Partnership community, this was not a time to turn inwards. Instead, it was a time for solidarity at a global and national level, underpinned by the solidarity expressed between health workers across borders. Working with the ESTHER Alliance and Medics.Academy, and with early and enthusiastic support from our partners at the World Health Organization, we worked furiously over the following two weeks to provide an international stage for this expression of solidarity. The result was ‘Partnerships in an Era of Covid-19’, a one-day online conference which attracted 25 speakers from three continents and 750 registered attendees from 54 countries. We used Zoom and in addition, over 100 resources were shared and discussed through the medium of Slack. -

Risk Factors for Podoconiosis: Kamwenge District, Uganda September 2015 Christine Kihembo , Mbchb, MIPH Fellow, Cohort 2015

Public Health Fellowship Program – Field Epidemiology Track Risk Factors for Podoconiosis: Kamwenge District, Uganda September 2015 Christine Kihembo , MBchB, MIPH Fellow, Cohort 2015 Podoconiosis: Non-filarial elephantiasis . Contact with irritant soils: red clays from alkaline volcanic rock . Areas >1000m (330ft), Annual rainfall of 1000mm 2 Podoconiosis in Kamwenge Disease process Mineral particles penetrate skin Taken up by macrophages in lymphatics Inflammation: (Genetically predisposed) Lymphatic Fibrosis and Blockade Disabling Lymphedema Podoconiosis not documented in Kamwenge district Kamwenge 5 Podoconiosis in Kamwenge Events leading to investigation Lymphatic Filariasis Mapping by MOH, VCD 2014 Early 2015 Aug 2015 Sept 2015 Investigation nd WHO,VCD alerted of 2 Alert increased cases of “elephantiasis” 6 Podoconiosis in Kamwenge Objectives . Identify risk factors for Podoconiosis in Kamwenge district . Provide evidence for public health action 7 Podoconiosis in Kamwenge Case definition . Suspected Case: Asymmetrical lower limb swelling (non-pitting oedema) for ≥1mon, plus ≥1 of: – Itching of skin, burning sensation – Plantar-oedema (swelling of sole of foot) – Lymph ooze – Prominent skin markings – Hyperkeratosis(skin hardening) – Formation of moss-like papillomata/nodules – Rigid toes in a Kamwenge resident. Probable Case: Suspected case with negative microfilaria antigen immunological card test 8 Podoconiosis in Kamwenge Active Case finding in collaboration with: . District health team . Village health team . Office of the -

Rapid Qualitative Research Methods During Complex Health Emergencies: 9 a Systematic Review of the Literature 10 11 Ginger A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery 1 This is the accepted version of the article titled “Rapid Qualitative Research Methods during Complex 2 Health Emergencies: A Systematic Review of the Literature” by G. Johnson and C. Vindrola-Padros, 3 which was published in Social Science and Medicine 2017:189:63-75, 4 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.029 5 6 7 8 Rapid Qualitative Research Methods during Complex Health Emergencies: 9 A Systematic Review of the Literature 10 11 Ginger A. Johnsona,b* and Cecilia Vindrola-Padrosc 12 13 a Anthrologica, Oxford, United Kingdom 14 b Department of Anthropology, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas 15 c Department of Applied Health Research, University College London, United Kingdom 16 17 18 ABSTRACT 19 20 The 2013-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa highlighted both the successes and limitations of social 21 science contributions to emergency response operations. An important limitation was the rapid and 22 effective communication of study findings. A systematic review was carried out to explore how rapid 23 qualitative methods have been used during global heath emergencies to understand which methods are 24 commonly used, how they are applied, and the difficulties faced by social science researchers in the 25 field. We also asses their value and benefit for health emergencies. The review findings are used to 26 propose recommendations for qualitative research in this context. Peer-reviewed articles and grey 27 literature were identified through six online databases. An initial search was carried out in July 2016 and 28 updated in February 2017. -

Building Resilient Sub-National Health Systems – Strengthening Leadership and Management Capacity of District Health Management Teams

Building resilient sub-national health systems – Strengthening Leadership and Management Capacity of District Health Management Teams 20-22 April, 2016, Freetown, Sierra Leone Technical Workshop Report 0 | P a g e WHO/HIS/SDS/2016.14 © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email:[email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. -

Abstract Book

REGIONAL MEETING AFRICA KAMPALA, UGANDA JUNE 28–30, 2021 SCIENCE · INNOVATION · POLICIES ABSTRACT BOOK REGIONAL MEETING AFRICA KAMPALA, UGANDA JUNE 28–30, 2021 SCIENCE · INNOVATION · POLICIES ABSTRACT BOOK Contents Message from the former Prime Minister of Uganda v Message from the Minister of Health, Uganda vi Message from the Vice Chancellor of Makerere University vii Message from the World Health Summit International President viii Message from the Chair, Scientific Committee, WHS ix Message from the Chair, Regional Organizing Committee, WHS x Message from the Chair, Publicity Committee, WHS xi FINAL PROGRAMME xii FINAL PROGRAMME xii Summary xii Day 1 program xii Day 2 program xii Day 1 Program 1 KEYNOTE SPEECH 1: The COVID-19 pandemic in Africa 2 KEYNOTE 2: Pandemic Preparedness in the Era of COVID-19 5 PANEL DISCUSSION 1 (PD1): Mobility & Assistive Technology Access 7 PANEL DISCUSSION 2 (PD2): Women in Global Health 10 SIDE EVENT 1: Non-Communicable diseases and COVID-19 (Round table discussion) 15 WORKSHOP 1 (WS1): Biomedical Innovations to Eliminate Priority Infectious Diseases 19 WORKSHOP 2 (WS2): Rural Health Centers of Excellence 23 KEYNOTE 3: Africa’s Journey Towards Achieving the SDGs and Universal Health Coverage 28 PANEL DISCUSSION 3 (PD3): Research Capacity Strengthening in the Era of UHC & SDGs 31 PANEL DISCUSSION 4 (PD4): Perspectives on Sustainable Health 36 SIDE EVENT (SE1): The Lancent NCD commission 41 WORKSHOP 3 (WS3): COVID-19 Variants 44 WORKSHOP 4 (WS4): Dealing with Falsified & Substandard Medicines in Africa -

International Research and Innovations Dissemination

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH AND INNOVATIONS DISSEMINATION CONFERENCE APRIL 20-21, 2015 - HOTEL AFRICANA BOOK OF ABSTRACTS THEME: COMMUNITY TRANSFORMATION THROUGH RESEARCH, INNOVATIONS AND KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION CONFERENCE PROGRAMME DAY 1 – MONDAY APRIL 20 , 2015 MORNING SESSION 08.00 – 12.45 VENUE : NILE HALL 08.00 – 09.00 Registration of participants 09.00 – 9.30 Welcome Remarks, Chairperson, Conference Organising Committee 09.30– 10.30 Session 1: Plenary: Invited Papers Chairperson : Prof. George Nasinyama, Makerere University Special Paper 1: Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers (VHFs) by Dr. Monica Musenero Masanza, Assistant Commissioner,Epidemiology and Surveillance,Ministry of Health Special Paper 2: The future of food security in Africa’ By Prof. George William Otim- Nape, African Innovations Institute AFRII 10.30 – 11.00 HEALTH BREAK OPENING SESSION: 11:00 – 12.00 CHAIRPERSON – Prof. Charles Kwesiga, Executive Director, Uganda Industrial Research Institute, Nakawa - Kampala The Uganda National Anthem East African Community Anthem Anthem of the Government of Sweden Makerere University Anthem Remarks by the Vice Chancellor, Makerere University – Prof. John Ddumba-Ssentamu Remarks by the Chairperson Makerere University Council , Eng. Dr. Charles Wana-Etyem Remarks by the Ambassador of Sweden to Uganda, H.E Urban Andersson Remarks by the Chancellor Makerere University, Prof. George Mondo Kagonyera Address by Chief Guest, Minister of Education, Sports, Science and Technology, Hon. Jessica Alupo 12.00 – 12. 30 Keynote paper by Prof. Love Ekenberg, Professor of Mathematics, Stockholm University, Sweden 12.30 – 12.45 Discussion 12.45 – 14.00 LUNCH BREAK BREAKOUT/PARALLEL SESSIONS SUB-THEME 1: HEALTH AND HEALTH SYSTEMS CHAIRPERSON : Dr Jaran Eriksen, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Karolinska Institutet VENUE : ORANGE HALL Key Paper : by Prof.