Scenic Resource Protection Guide for the Hudson River Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Burroughs for ATQ: 19Th C

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REviEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, writer, Scenic Hudson Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editorial Board Art Director Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, Richard Deon Bard College Business Manager Col. Lance Betros, Professor and deputy head, Andrew Villani Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Susan Ingalls Lewis, Assistant Professor of History, a year by the Hudson River Valley State University of New York at New Paltz Institute at Marist College. Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- James M. Johnson, Executive Director Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Research Assistants Fordham University Elizabeth Vielkind H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Emily Wist Vassar College Hudson River Valley Institute Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Advisory Board Marist College Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Franklin & Marshall College Dr. Frank Bumpus Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President of Academic Frank J. Doherty Affairs, Marist College, Chair Patrick Garvey David Woolner, Associate Professor of History Marjorie Hart & Political Science, Marist College, Franklin Maureen Kangas & Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park Barnabas McHenry Alex Reese Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2008 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Tel: 845-575-3052 Post: The Hudson River Valley Review Fax: 845-575-3176 c/o Hudson River Valley Institute E-mail: [email protected] Marist College, 3399 North Road, Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.org Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). -

The Hudson River Valley Review

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REviEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, writer, Scenic Hudson Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editorial Board Art Director Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, Richard Deon Bard College Business Manager Col. Lance Betros, Professor and deputy head, Andrew Villani Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Susan Ingalls Lewis, Assistant Professor of History, a year by the Hudson River Valley State University of New York at New Paltz Institute at Marist College. Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- James M. Johnson, Executive Director Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Research Assistants Fordham University Elizabeth Vielkind H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Emily Wist Vassar College Hudson River Valley Institute Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Advisory Board Marist College Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Franklin & Marshall College Dr. Frank Bumpus Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President of Academic Frank J. Doherty Affairs, Marist College, Chair Patrick Garvey David Woolner, Associate Professor of History Marjorie Hart & Political Science, Marist College, Franklin Maureen Kangas & Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park Barnabas McHenry Alex Reese Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2008 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Tel: 845-575-3052 Post: The Hudson River Valley Review Fax: 845-575-3176 c/o Hudson River Valley Institute E-mail: [email protected] Marist College, 3399 North Road, Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.org Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). -

John Burroughs' Writing Retreats

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REviEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, writer, Scenic Hudson Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editorial Board Art Director Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, Richard Deon Bard College Business Manager Col. Lance Betros, Professor and deputy head, Andrew Villani Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Susan Ingalls Lewis, Assistant Professor of History, a year by the Hudson River Valley State University of New York at New Paltz Institute at Marist College. Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- James M. Johnson, Executive Director Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Research Assistants Fordham University Elizabeth Vielkind H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Emily Wist Vassar College Hudson River Valley Institute Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Advisory Board Marist College Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Franklin & Marshall College Dr. Frank Bumpus Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President of Academic Frank J. Doherty Affairs, Marist College, Chair Patrick Garvey David Woolner, Associate Professor of History Marjorie Hart & Political Science, Marist College, Franklin Maureen Kangas & Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park Barnabas McHenry Alex Reese Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2008 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Tel: 845-575-3052 Post: The Hudson River Valley Review Fax: 845-575-3176 c/o Hudson River Valley Institute E-mail: [email protected] Marist College, 3399 North Road, Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.org Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). -

West of Hudson Draft Unit Management Plan

West of Hudson UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT Towns of Saugerties, Esopus, Plattekill, Ulster, Hamptonburgh, Montgomery, Warwick, and New Windsor Counties of Orange and Ulster October 2018 DIVISION OF LANDS AND FORESTS Bureau of Forest Resource Management NYSDEC Region 3 21 South Putt Corners RD New Paltz, NY 12561 www.dec.ny.gov This page intentionally left blank 1 West of Hudson Unit Management Plan A planning unit consisting of approximately 8,000 acres encompassing 7 State Forests in Orange and Ulster Counties: Mt. Peter Hawk Watch, Stewart State Forest, Pochuck Mountain State Forest, Highwoods MUA, Hemlock Ridge MUA, Turkey Point State Forest, Black Creek State Forest October 2018 Prepared by the West of Hudson Unit Management Planning Team: Matthew C. Paul, Senior Forester Patrick Miglio, Real Property Surveyor Nathan Ermer, Wildlife Biologist Michael Disarno, Fisheries Biologist William Bernard, Operations Manager Evan Masten, Forester I Pine Roehrs, Senior Natural Resource Planner Acknowledgments The West of Hudson Unit Management Planning Team would like to gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all those who contributed to this plan. We particularly would like to thank the following organizations for the information they provided: Stewart Park and Reserve Coalition (SPARC), Stewards of Stewart (SOS), The John Burroughs Association, Fats in the Cats Bicycle Club, and Scenic Hudson New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Lands and Forests Bureau of Forest Resource Management Region 3 2 This page is intentionally -

JOHN BURROUGHS by Monroe S

Jottings From The Golf Course Journal JOHN BURROUGHS By Monroe S. Miller Sit down some time and make a list of all the things that make you proud to be part of the profession we are in. My list would be very long. And if we compared those lists among ourselves, there are many characteristics and features that would appear on everybody's list. Chances are good we all take pride in our land stewardship. Golf courses offer open spaces, wildlife habitat, healthy recreation, green spaces and more than I have room to repeat here. Their role is even more special in the many urban areas where so many are found. Riverby from the orchard. Land stewardship long ago piqued my interest in nature and landscapes, even as a farm kid. And isn't it inter- esting that two of the foremost envi- ronmental thinkers and natural writers — John Muir and Aldo Leopold — lived so close, especially to those of On the porch at Woodchuck Lodge. us in south central Wisconsin. The parallels, a generation apart, are astonishing. Muir grew up near Portage and attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Leopold bought a farm in the sand country near Portage and was a professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Historians add a third albeit lesser known name to these two nat- uralists — historian Frederick Jackson Turner. Is it an accident — pure chance — that three notables arose from a View of the Catskills from Woodchuck Wisconsin neighborhood? Why is our Lodge at the turn of the century. John Muir and John Burroughs, Pasadena, California. -

John Burroughs Black Creek Trail Plan

N Eltings Rd d R rs e n r o C LILLY s LAKE ley aw 15 H Tony WIlliams Swartekill Rd 16 B la ck Town Park Loughran Ln C re e k Martin Ave d R e d i s r P e O U v Chodikee Lake S i S R E Illinois S Boat Launch Chodik e R Mountain 12 N ee Lak d New Paltz Rd d CHODIKEE t R er J LAKE k Blacka Creek Canoe c n A e Valli Rd d H W y Berean &o Kayak Launch H o o le l d l i d i k F d R Pa k Park d e e Black Creek John Burroughs 44 N e d R R i Nature Sactuary e v State Forest k k e r a s i i L S Chodikee d B e Rd Gordon Highland O Y 299 L L D Property 44 Black Creek 9W S Burroughs Dr 9W Preserve Franny Reese State Park Walkway Over HUDSON RIVER the Hudson 9 Y D E 9 9 H 40A P A R K 41 BlackBlack CreekCreek TrailTrail Plan Bike | Paddle | Hike Black Creek Trail Table of Contents Sections Maps & Graphics 1| Introduction 7 Trail Concept 6-7 1.1| Executive Summary 8 1.2| Conserved Lands 11 Conserved Lands 10 2| Existing Conditions 13 Conserved Lands 12-13 2.1| Access & Connections 15 Issues 15 2.2| Trail Conditions 16 2.3| Educational Programing 17 2.4| Corridor Ecology 18 2.5| Economic Development 19 Potential Redevelopment Sites 19 2| Recommendations 21 Trail Route 20-21 3.1| Recommended Trail Route 23 Trail Route 23 3.1.1| Biking 24 Ose Road Crossing & BCSF Entrance 24 3.1.2| Paddling 25 3.1.3| Hiking 26 Hiking Trail Detail 27 3.2| Access Improvements 29 Trail Access 29 3.3| Wayfinding & Branding 30 3.4| Environmental Protection 31 3.5| Land Conservation 32 3.6| Educational Programing 33 3.7| Revitalize Properties 34 3.8| Develop Businesses 35 3.9| -

JOHN BURROUGHS by Monroe S

Jottings From The Golf Course Journal JOHN BURROUGHS By Monroe S. Miller Sit down some time and make a list of all the things that make you proud to be part of the profession we are in. My list would be very long. And if we compared those lists among ourselves, there are many characteristics and features that would appear on everybody's list. Chances are good we all take pride in our land stewardship. Golf courses offer open spaces, wildlife habitat, healthy recreation, green spaces and more than I have room to repeat here. Their role is even more special in the many urban areas where so many are found. Riverby from the orchard. Land stewardship long ago piqued my interest in nature and landscapes, even as a farm kid. And isn't it inter- esting that two of the foremost envi- ronmental thinkers and natural writers — John Muir and Aldo Leopold — lived so close, especially to those of On the porch at Woodchuck Lodge. us in south central Wisconsin. The parallels, a generation apart, are astonishing. Muir grew up near Portage and attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Leopold bought a farm in the sand country near Portage and was a professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Historians add a third albeit lesser known name to these two nat- uralists — historian Frederick Jackson Turner. Is it an accident — pure chance — that three notables arose from a View of the Catskills from Woodchuck Wisconsin neighborhood? Why is our Lodge at the turn of the century. John Muir and John Burroughs, Pasadena, California. -

Passport to Your National Parks Cancellation Station Locations

Updated 10/01/19 Passport To Your National Parks New listings are in red Cancellation Station Locations While nearly all parks in the National Park Civil Rights Trail; Selma—US Civil Rights Bridge, Marble Canyon System participate in the Passport program, Trail Grand Canyon NP—Tuweep, North Rim, participation is voluntary. Also, there may Tuskegee Airmen NHS—Tuskegee; US Civil Grand Canyon, Phantom Ranch, Tusayan be parks with Cancellation Stations that are Rights Trail Ruin, Kolb Studio, Indian Garden, Ver- not on this list. Contact parks directly for the Tuskegee Institute NHS—Tuskegee Institute; kamp’s, Yavapai Geology Museum, Visi- exact location of their Cancellation Station. Carver Museum—US Civil Rights Trail tor Center Plaza, Desert View Watchtower For contact information visit www.nps.gov. GC - Parashant National Monument—Arizo- To order the Passport book or stamp sets, call ALASKA: na Strip, AZ toll-free 1-877-NAT-PARK (1-877-628-7275) Alagnak WR—King Salmon Hubbell Trading Post NHS—Ganado or visit www.eParks.com. Alaska Public Lands Information Center— Lake Mead NRA—Katherine Landing, Tem- Anchorage, AK ple Bar, Lakeshore, Willow Beach Note: Affiliated sites are listed at the end. Aleutian World War II NHA—Unalaska Montezuma Castle NM—Camp Verde, Mon- Aniakchak NM & PRES—King Salmon tezuma Well PARK ABBREVIATIONS Bering Land Bridge N PRES—Kotz, Nome, Navajo NM—Tonalea, Shonto IHS International Historic Site Kotzebue Organ Pipe Cactus NM—Ajo NB National Battlefield Cape Krusenstern NM—Kotzebue Petrified Forest NP—Petrified Forest, The NBP National Battlefield Park NBS National Battlefield Site Denali NP—Talkeetna, Denali NP, Denali Painted Desert, Painted Desert Inn NHD National Historic District Park Pipe Spring NM—Moccasin, Fredonia NHP National Historical Park Gates of the Arctic NP & PRES—Bettles Rainbow Bridge NM—Page, Lees Ferry NHP & EP Nat’l Historical Park & Ecological Pres Field, Coldfoot, Anaktuvuk Pass, Fair- Saguaro NP—Tucson, Rincon Mtn. -

Abouttown Summer 2018 Calendar

BE SURE TO CHECK WITH THE SPONSORS OF EVENTS SUNDAY, JUNE 3 FRIDAY, JUNE 8 FOR CHARGES, OR IN CASE OF TYPOS. The Magic of Unison Gala celebrating 43 years of Second Fridays Swing Dance with live music by the Unison Arts Center. Magic show by world Metropolitan Hot Club; enjoy a night of swing renown magician Mark Mitton; music offered by dance with Emily Vanston; wine and refreshments Big Joe Fitz and the Lo-Fi's. Dinner catered by will be available. Purchase tickets at door: Inter- JUNE Bridgecreek Catering and a silent auction. Also cel- mediate/ Advanced swing lessons from 6:30 to 7:30 SATURDAY, JUNE 2 ebrating the 75th birthday of Stuart Bigley, one of PM ($10); must be comfortable with 8-count Hudson Valley Community Dance. English Dance the first founders, as well as the new Executive Di- swing out; Intro/ Beginner lesson for new dancers in Port Ewen. Margaret Bary calling with Tiddely rector, Alexandra Baer, in a gallery exhibit – Works from 7:30 to 8 PM (No charge). Swing Dance Pom. Admission $10 Full time students $5. Eng- from Past and Present Directors. $125/person or Party, 8 to 10 PM ($12 non-member; $10 students lish Country dance lesson 7:00PM Required for $100/person if you reserve table of 8. 5 PM. and members). new dancers.Even if you are experienced, come for Alexandra Baer. 845-255.1559. www.unisonarts.org. [email protected] ; Unison Arts Center, 68 Mountain Rest Rd, New Paltz the lesson. We need your help. 7:00pm – 10:30pm 845.255.1559, www.unisonarts.org. -

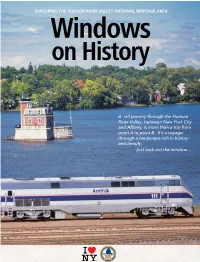

Windows on History

EXPLORING THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Windows on History A rail journey through the Hudson River Valley, between New York City and Albany, is more than a trip from point A to point B. It’s a voyage through a landscape rich in history and beauty. Just look out the window… Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H W ELCOME TO THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY! RAVELING THROUGH THIS HISTORIC REGION, you will discover the people, places, and events that formed our national identity, and led Congress to designate the Hudson River Valley as a National Heritage Area in 1996. The Hudson River has also been designated one of our country’s Great American Rivers. TAs you journey between New York’s Pennsylvania station and the Albany- Rensselaer station, this guide will interpret the sites and features that you see out your train window, including historic sites that span three centuries of our nation’s history. You will also learn about the communities and cultural resources that are located only a short journey from the various This project was made station stops. possible through a partnership between the We invite you to explore the four million acres Hudson River Valley that make up the Hudson Valley and discover its National Heritage Area rich scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational and I Love NY. -

Hudson Valley & Catskill Regions TRAVEL GUIDE 2017–2018

ulstercountyalive.com ULSTER COUNTY Hudson Valley & Catskill Regions TRAVEL GUIDE 2017–2018 Festival Fun Easy Escapes Craft Beverages Sweet Dreams The Region’s Best Events Boating, Trails and Tours Find a New Favorite Over 200 Places to Stay A nationally ranked public university here in the HUDSON VALLEY Come explore our campus… visit the SAMUEL DORSKY MUSEUM OF ART, attend a PLANETARIUM SHOW or OBSERVATORY telescope viewing, see a MAINSTAGE THEATRE production, or check our WEBSITE for more events. www.newpaltz.edu THE ADIRONDACKS NIAGARA FALLS ROCHESTER Ulster County is in the southeast part of New SYRACUSE BUFFALO York State, 90 miles north of New York City and ALBANY a half-hour south of Albany. Ulster County, which is immediately west of the Hudson River, is easily accessible with three exits on the New York State Thruway. Much of the county is within the Catskill Mountains and the Shawangunk Ridge. ULSTER COUNTY NEW YORK CITY Ashokan High Point Welcome to Ulster County Stretching over 1,000 square miles of scenic woodlands, it feels like a world away. The beauty and dotted with picture-perfect county is a national leader in preservation, villages and towns, Ulster County is recently featured in National Geographic a four-season playground ready to be for its environmental achievements. Ulster explored. From the iconic Hudson River County is proud to be the first and only to the majestic Catskill Mountains, the net-carbon-neutral county in New York. county contains everything you need The county’s diverse towns and villages to enjoy the great outdoors. Our farms each have their own distinct personality. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property historic name Camp Caesar other names/site number Webster County 4-H Camp 2. Location street & number 4868 Webster Road ] not for publication city or town Cowen |~1 vicinity state West Virginia code 101 zip code 26206 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this 1^1 nomination l~l request for detennination of eligibility mgets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and mreis the proredural and professional requirements set for in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^] meets d does not mrar the NationaWlegister criteria. JI recoirimend that this property be considered significant l~1 natiojplly E3 statewid|e E*3 lqcqJl^(See' continuation~ sheet for additional comments.) j ___________ _________ Signature of certifying official/Title Date / West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office \i; \} State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property l~~l meets I~l does not meet the National Register criteria. (l~1 See Continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I herebv<5ertiry that the property is: Signature or the Keeper Date of Action 5j entered in the National Register, n See continuation sheet d determined eligible for the National Register. U D See continuation sheet EH determined not eligible for the National Register.