John Burroughs' Writing Retreats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Burroughs for ATQ: 19Th C

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REviEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, writer, Scenic Hudson Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editorial Board Art Director Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, Richard Deon Bard College Business Manager Col. Lance Betros, Professor and deputy head, Andrew Villani Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Susan Ingalls Lewis, Assistant Professor of History, a year by the Hudson River Valley State University of New York at New Paltz Institute at Marist College. Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- James M. Johnson, Executive Director Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Research Assistants Fordham University Elizabeth Vielkind H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Emily Wist Vassar College Hudson River Valley Institute Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Advisory Board Marist College Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Franklin & Marshall College Dr. Frank Bumpus Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President of Academic Frank J. Doherty Affairs, Marist College, Chair Patrick Garvey David Woolner, Associate Professor of History Marjorie Hart & Political Science, Marist College, Franklin Maureen Kangas & Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park Barnabas McHenry Alex Reese Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2008 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Tel: 845-575-3052 Post: The Hudson River Valley Review Fax: 845-575-3176 c/o Hudson River Valley Institute E-mail: [email protected] Marist College, 3399 North Road, Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.org Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). -

Catskill Watershed Corporation Annual Report 2019

Catskill Watershed Corporation Annual Report 2019 Our Neighborhood The Catskill Watershed Corporation’s environ- mental protection, economic development and education programs are conducted in 41 towns that lie wholly or partially within the NYC Cats- kill-Delaware Watershed region which supplies water to 9.5 million people in New York City and four upstate counties. 2 Arrivals and Departures he CWC welcomed a new Board member and said farewell to a long time Direc- tor. Mark McCarthy, left, former Supervisor of Neversink, Sullivan County Legisla- tor and a member of the CWC Board for the past five years stepped down following the CWC Annual Meeting April 2, 2019. Chris Mathews, current Supervisor for the Town of Neversink was elected to fill Mark’s seat. Mark McCarthy Christopher Mathews Cambria Tallman Skylie Roberts he CWC added two staff members to the next generation of Watershed Stewards: Cambria Tallman as Administrative Assistant and Skylie Roberts as Bookkeeper. Kimberlie Ackerley Diane Galusha Leo LaBuda Wendy Loper e bid farewell to several long-time CWC staff members. Kimberlie Ackerley, Program Specialist— Stormwater; Diane Galusha, Public Education Direc- tor; Leo LaBuda, Environmental Engineering Spe- cialist; and Wendy Loper, Bookkeeper all departed after many years of valued service. 3 A Message from the Executive Director 019 was a very remarkable year for CWC. 2019 marked 23 years of service for the organization. Our dedicated staff has done an incredible job at reorganizing while strengthening our programs and services. The new office building will increase the value of services delivered directly to Watershed residents, businesses and users of the water supply. -

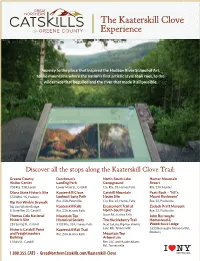

The Kaaterskill Clove Experience

The Kaaterskill Clove Experience Journey to the place that inspired the Hudson River School of Art, to the mountains where the nation’s fi rst artistic style took root, to the wilderness that beguiled and the river that made it all possible. Discover all the stops along the Kaaterskill Clove Trail: Greene County Dutchman’s North-South Lake Hunter Mountain Visitor Center Landing Park Campground Resort 700 Rte. 23B, Leeds Lower Main St., Catskill Cty. Rte. 18, Haines Falls Rte. 23A, Hunter Olana State Historic Site Kaaterskill Clove Catskill Mountain Pratt Rock – “NY’s 5720 Rte. 9G, Hudson Lookout/Long Path House Site Mount Rushmore” Rip Van Winkle Skywalk Rte. 23A, Palenville Cty. Rte. 18, Haines Falls Rte. 23, Prattsville Rip Van Winkle Bridge Kaaterskill Falls Escarpment Trail at Zadock Pratt Museum & State Rte. 23, Catskill Rte. 23A, Haines Falls North-South Lake Rte. 23, Prattsville Thomas Cole National Mountain Top Scutt Rd., Haines Falls John Burroughs Historic Site Historical Society The Huckleberry Trail Homestead & 218 Spring St., Catskill 5132 Rte. 23A, Haines Falls Next to Lake Rip Van Winkle Woodchuck Lodge Historic Catskill Point Kaaterskill Rail Trail Lake Rd., Tannersville 1633 Burroughs Memorial Rd., Roxbury and Freightmasters Rte. 23A, Haines Falls Mountain Top Building Arboretum 1 Main St., Catskill Rte. 23C and Maude Adams Rd., Tannersville 1.800.355.CATS • GreatNorthernCatskills.com/Kaaterskill-Clove Travel a new path through America’s rst wilderness – Take a self-guided, set-your-own pace journey through history. Greene County Visitor Center Kaaterskill Clove Lookout/ Catskill Mountain House Site Start the trail at the Greene County Long Path Proceed through the North-South Lake Visitor Center located at Exit 21 off the Follow Main Street west to the traffi c light Campground entrance (see previous NYS Thruway (I-87) and stop in to get and make a left onto Bridge Street. -

Wedding Issue

Catskill Mountain Region February 2013 GUIDEwww.catskillregionguide.com WEDDING ISSUE The Catskill Mountain Foundation Presents THe BlueS Hall oF Fame NIgHT aT THe orpHeum New York Blues Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony and Concert This performance is funded, in part, by Friends of the Orpheum (FOTO) with recent inductees Professor Louie & The Crowmatix, Bill Sims, Jr., Michael Packer, and Sonny Rock Awards going to Big Joe Fitz, Kerry Kearney and more great performers to be announced with Greg Dayton opening and special guests the Greene Room Show Choir Saturday, February 16, 2013 8pm (doors open at 7pm) Tickets: $25 in advance, $30 at the door For tickets, visit www.catskillmtn.org or call 518 263 2063 Orpheum Performing Arts Center • 6022 Main St., Tannersville, NY 12485 TABLE OF www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 28, NUMBER 2 February 2013 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation CONTENTS EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Rita Adami • Steve Friedman Garan Santicola • Albert Verdesca CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Tara Collins, Jeff Senterman, Carol and David White Additional content provided by Brandpoint Content. ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee Toni Perretti Laureen Priputen PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing DISTRIBUTION Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: January 6 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box On the cover: Wedding at the summit of Hunter Mountain. 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ Photo by John Iannelli, www.iannelliphoto.com. -

The Hudson River Valley Review

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REviEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, writer, Scenic Hudson Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editorial Board Art Director Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, Richard Deon Bard College Business Manager Col. Lance Betros, Professor and deputy head, Andrew Villani Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Susan Ingalls Lewis, Assistant Professor of History, a year by the Hudson River Valley State University of New York at New Paltz Institute at Marist College. Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- James M. Johnson, Executive Director Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Research Assistants Fordham University Elizabeth Vielkind H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Emily Wist Vassar College Hudson River Valley Institute Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Advisory Board Marist College Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Franklin & Marshall College Dr. Frank Bumpus Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President of Academic Frank J. Doherty Affairs, Marist College, Chair Patrick Garvey David Woolner, Associate Professor of History Marjorie Hart & Political Science, Marist College, Franklin Maureen Kangas & Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park Barnabas McHenry Alex Reese Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2008 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Tel: 845-575-3052 Post: The Hudson River Valley Review Fax: 845-575-3176 c/o Hudson River Valley Institute E-mail: [email protected] Marist College, 3399 North Road, Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.org Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). -

Wagner Vineyards

18_181829 bindex.qxp 11/14/07 11:59 AM Page 422 Index Albany Institute of History & Anthony Road Wine Company AAA (American Automobile Art, 276, 279 (Penn Yann), 317 Association), 34 Albany International Airport, Antique and Classic Boat Show AARP, 42 257–268 (Skaneateles), 355 Access-Able Travel Source, 41 Albany LatinFest, 280 Antique Boat Museum Accessible Journeys, 41 Albany-Rensselaer Rail Station, (Clayton), 383 Accommodations, 47 258 Antique Boat Show & Auction best, 5, 8–10 Albany Riverfront Jazz Festival, (Clayton), 30 Active vacations, 63–71 280 Antiques Adair Vineyards (New Paltz), Albany River Rats, 281 best places for, 12–13 229 Albright-Knox Art Gallery Canandaigua Lake, 336 Adirondack Balloon Festival (Buffalo), 396 Geneva, 348 (Glens Falls), 31 Alex Bay Go-Karts (near Thou- Hammondsport, 329 Adirondack Mountain Club sand Islands Bridge), 386 Long Island, 151–152, 159 (ADK), 69–71, 366 Alison Wines & Vineyards Lower Hudson Valley, 194 Adirondack Museum (Blue (Red Hook), 220 Margaretville, 246 Mountain Lake), 368 Allegany State Park, 405 Mid-Hudson Valley, 208 The Adirondacks Alternative Leisure Co. & Trips Rochester, 344 northern, 372–381 Unlimited, 40 Saratoga Springs, 267 southern, 364–372 Amagansett, 172, 179 Skaneateles, 355, 356 suggested itinerary, 56–58 America the Beautiful Access southeastern Catskill region, Adirondack Scenic Railroad, Pass, 40 231 375–376 America the Beautiful Senior Sullivan County, 252 African-American Family Day Pass, 42 Upper Hudson Valley, 219 (Albany), 280 American Airlines Vacations, 45 -

West of Hudson Draft Unit Management Plan

West of Hudson UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT Towns of Saugerties, Esopus, Plattekill, Ulster, Hamptonburgh, Montgomery, Warwick, and New Windsor Counties of Orange and Ulster October 2018 DIVISION OF LANDS AND FORESTS Bureau of Forest Resource Management NYSDEC Region 3 21 South Putt Corners RD New Paltz, NY 12561 www.dec.ny.gov This page intentionally left blank 1 West of Hudson Unit Management Plan A planning unit consisting of approximately 8,000 acres encompassing 7 State Forests in Orange and Ulster Counties: Mt. Peter Hawk Watch, Stewart State Forest, Pochuck Mountain State Forest, Highwoods MUA, Hemlock Ridge MUA, Turkey Point State Forest, Black Creek State Forest October 2018 Prepared by the West of Hudson Unit Management Planning Team: Matthew C. Paul, Senior Forester Patrick Miglio, Real Property Surveyor Nathan Ermer, Wildlife Biologist Michael Disarno, Fisheries Biologist William Bernard, Operations Manager Evan Masten, Forester I Pine Roehrs, Senior Natural Resource Planner Acknowledgments The West of Hudson Unit Management Planning Team would like to gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all those who contributed to this plan. We particularly would like to thank the following organizations for the information they provided: Stewart Park and Reserve Coalition (SPARC), Stewards of Stewart (SOS), The John Burroughs Association, Fats in the Cats Bicycle Club, and Scenic Hudson New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Lands and Forests Bureau of Forest Resource Management Region 3 2 This page is intentionally -

A Directory of Primary and Community Resources in the PROBE Area

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 079 201 SO 005 974 AUTHOR Whitehill, Willian E., Jr., Comp.; And Others TITLE A Directory of Primary and Community Resources in the PROBE Area.. INSTITUTION Catskill Area School Study Council,_Oneonta, N.Y.; Otsego County Board of Cooperative Educational Services, Oneonta, N.Y. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Projects to Advance Creativity in Education. - PUB DATE 68 NOTE 210p. EDRS PRICE' MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS *Community Resources; *Directories; Elementary Education; Resource Guides; Secondary Education; *Social Studies; Teacher Developed Materials IDENTIFIERS ESEA Title III; New York; *Project Probe ABSTRACT Community and area resources -- consisting of persons, places, or objects -- gathered from the regions comprising Chenango,.Delaware, and Otsego Countries, are listed in this directory. Teachers, local historians, and PROBE staff identified resources which could be introduced to K-12 teachers. In addition to a brief introduction, the book contains two major chapters, the first containing lists of primary sources and cultural and educational resources in communities, arranged by county and tLen by business or industry, church, historical sites, libraries, local organizations, museums, public buildings, private collections and schools. Human resources include the local historian, political figures, and other significant persons. The second major chapter, a specialized section, -offers listings of geologidal resources in the three counties; an archeological survey and description -

2017 Interim Planning Assessment for Mine Kill State Park, Max V

2017 Interim Planning Assessment for Mine Kill State Park, Max V. Shaul State Park and John Burroughs Memorial State Historic Site July 10, 2017 2017 Interim Planning Assessment for Mine Kill and Max V Shaul State Parks and John Burroughs Memorial State Historic Site: Title Page 2017 Interim Planning Assessment* for Mine Kill State Park, Max V. Shaul State Park and John Burroughs Memorial State Historic Site Schoharie and Delaware Counties Towns of Fulton, Blenheim, Gilboa and Roxbury Prepared by The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Completed: July 10, 2017 Contacts: Alane Ball Chinian, Regional Director Diana Carter, Director Saratoga/Capital District Park Region Resource and Facility Planning 19 Roosevelt Drive OPRHP Saratoga Springs, NY 12866 625 Broadway 518-584-2000 Albany, NY 12207 518-486-2909 * The operating license granted to NYPA is currently under review for renewal by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Some of the proposed action items for Mine Kill State Park in this planning document will be finalized when negotiations for the renewed operating license are complete. Page 3 2017 Interim Planning Assessment for Mine Kill and Max V Shaul State Parks and John Burroughs Memorial State Historic Site: Tables of Contents, Figures and Tables Table of Contents I. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................................7 A. Background ........................................................................................................................................... -

Massachusetts Massachusetts Office of Travel and Tourism, 10 Park Plaza, Suite 4510, Boston, MA 02116

dventure Guide to the Champlain & Hudson River Valleys Robert & Patricia Foulke HUNTER PUBLISHING, INC. 130 Campus Drive Edison, NJ 08818-7816 % 732-225-1900 / 800-255-0343 / fax 732-417-1744 E-mail [email protected] IN CANADA: Ulysses Travel Publications 4176 Saint-Denis, Montréal, Québec Canada H2W 2M5 % 514-843-9882 ext. 2232 / fax 514-843-9448 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: Windsor Books International The Boundary, Wheatley Road, Garsington Oxford, OX44 9EJ England % 01865-361122 / fax 01865-361133 ISBN 1-58843-345-5 © 2003 Patricia and Robert Foulke This and other Hunter travel guides are also available as e-books in a variety of digital formats through our online partners, including Amazon.com, netLibrary.com, BarnesandNoble.com, and eBooks.com. For complete information about the hundreds of other travel guides offered by Hunter Publishing, visit us at: www.hunterpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechani- cal, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Brief extracts to be included in reviews or articles are permitted. This guide focuses on recreational activities. As all such activities contain ele- ments of risk, the publisher, author, affiliated individuals and companies disclaim any responsibility for any injury, harm, or illness that may occur to anyone through, or by use of, the information in this book. Every effort was made to in- sure the accuracy of information in this book, but the publisher and author do not assume, and hereby disclaim, any liability for loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misleading information or potential travel problems caused by this guide, even if such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident or any other cause. -

JOHN BURROUGHS by Monroe S

Jottings From The Golf Course Journal JOHN BURROUGHS By Monroe S. Miller Sit down some time and make a list of all the things that make you proud to be part of the profession we are in. My list would be very long. And if we compared those lists among ourselves, there are many characteristics and features that would appear on everybody's list. Chances are good we all take pride in our land stewardship. Golf courses offer open spaces, wildlife habitat, healthy recreation, green spaces and more than I have room to repeat here. Their role is even more special in the many urban areas where so many are found. Riverby from the orchard. Land stewardship long ago piqued my interest in nature and landscapes, even as a farm kid. And isn't it inter- esting that two of the foremost envi- ronmental thinkers and natural writers — John Muir and Aldo Leopold — lived so close, especially to those of On the porch at Woodchuck Lodge. us in south central Wisconsin. The parallels, a generation apart, are astonishing. Muir grew up near Portage and attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Leopold bought a farm in the sand country near Portage and was a professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Historians add a third albeit lesser known name to these two nat- uralists — historian Frederick Jackson Turner. Is it an accident — pure chance — that three notables arose from a View of the Catskills from Woodchuck Wisconsin neighborhood? Why is our Lodge at the turn of the century. John Muir and John Burroughs, Pasadena, California. -

John Burroughs Black Creek Trail Plan

N Eltings Rd d R rs e n r o C LILLY s LAKE ley aw 15 H Tony WIlliams Swartekill Rd 16 B la ck Town Park Loughran Ln C re e k Martin Ave d R e d i s r P e O U v Chodikee Lake S i S R E Illinois S Boat Launch Chodik e R Mountain 12 N ee Lak d New Paltz Rd d CHODIKEE t R er J LAKE k Blacka Creek Canoe c n A e Valli Rd d H W y Berean &o Kayak Launch H o o le l d l i d i k F d R Pa k Park d e e Black Creek John Burroughs 44 N e d R R i Nature Sactuary e v State Forest k k e r a s i i L S Chodikee d B e Rd Gordon Highland O Y 299 L L D Property 44 Black Creek 9W S Burroughs Dr 9W Preserve Franny Reese State Park Walkway Over HUDSON RIVER the Hudson 9 Y D E 9 9 H 40A P A R K 41 BlackBlack CreekCreek TrailTrail Plan Bike | Paddle | Hike Black Creek Trail Table of Contents Sections Maps & Graphics 1| Introduction 7 Trail Concept 6-7 1.1| Executive Summary 8 1.2| Conserved Lands 11 Conserved Lands 10 2| Existing Conditions 13 Conserved Lands 12-13 2.1| Access & Connections 15 Issues 15 2.2| Trail Conditions 16 2.3| Educational Programing 17 2.4| Corridor Ecology 18 2.5| Economic Development 19 Potential Redevelopment Sites 19 2| Recommendations 21 Trail Route 20-21 3.1| Recommended Trail Route 23 Trail Route 23 3.1.1| Biking 24 Ose Road Crossing & BCSF Entrance 24 3.1.2| Paddling 25 3.1.3| Hiking 26 Hiking Trail Detail 27 3.2| Access Improvements 29 Trail Access 29 3.3| Wayfinding & Branding 30 3.4| Environmental Protection 31 3.5| Land Conservation 32 3.6| Educational Programing 33 3.7| Revitalize Properties 34 3.8| Develop Businesses 35 3.9|