The Catskills Are Among the Things Most Certain to Give Students a Greater Appreciation for Our Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center John Ingersoll 1625-1684 Bedfordshire, England Jonathan Ingersoll 1681-1760 Connecticut __________________________________________ Rev. Jonathan Ingersoll Jared Ingersoll 1713-1788 1722-1781 Ridgefield, Connecticut Stampmaster General for N.E Chaplain Colonial Troops Colonies under King George III French and Indian Wars, Champlain Admiralty Judge Grace Isaacs m. Jonathan Ingersoll Baron J.C. Van den Heuvel Jared Ingersoll, Jr. 1770-1823 1747-1823 1749-1822 Lt. Governor of Conn. Member Const. Convention, 1787 Judge Superior and Supreme Federalist nominee for V.P., 1812 Courts of Conn. Attorney General Presiding Judge, District Court, PA ___ _____________ Grace Ingersoll Charles Anthony Ingersoll Ralph Isaacs Ingersoll m. Margaret Jacob A. Charles Jared Ingersoll Joseph Reed Ingersoll Zadock Pratt 1806- 1796-1860 1789-1872 1790-1878 1782-1862 1786-1868 Married General Grellet State=s Attorney, Conn. State=s Attorney, Conn. Dist. Attorney, PA U.S. Minister to England, Court of Napoleon I, Judge, U.S. District Court U.S. Congress U.S. Congress 1850-1853 Dept. of Dedogne U.S. Minister to Russia nom. U.S. Minister to under Pres. Polk France Charles D. Ingersoll Charles Robert Ingersoll Colin Macrae Ingersoll m. Julia Helen Pratt George W. Pratt Judge Dist. Court 1821-1903 1819-1903 New York City Governor of Conn., Adjutant General, Conn., 1873-77 Charge d=Affaires, U.S. Legation, Russia, 1840-49 Theresa McAllister m. Colin Macrae Ingersoll, Jr. Mary E. Ingersoll George Pratt Ingersoll m. Alice Witherspoon (RI=s father) 1861-1933 1858-1948 U.S. Minister to Siam under Pres. -

COTI Guide to Crew Leadership for Trails

COTI Guide to Crew Leadership for Trails Produced by Colorado Outdoor Training Initiative (COTI) Funded in part by Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO) through the Colorado State Parks Trails Program. Second printing 2006 Acknowledgements THANK YOU COTI would like to acknowledge the people and organizations that volunteered their time and resources to the research, review, editing and piloting of these training materials. The content and illustrations of this document is a compilation of pre-existing sources, with a majority of the information provided by Larry Lechner, Protected Area Management Services; Crew Leader Manual, 5th Ed., Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado; Trail Construction and Maintenance Notebook. 2000 Ed. USDA Forest Service; and all of the other resources that are referenced at the end of each section. The COTI Instructor’s Guide to Teaching Crew Leadership for Trails was open to a statewide review prior to pilot training and publication. COTI would like to thank everyone who dedicated time to the review process. The following people provided valuable feedback on the project. CURRICULUM COMMITTEE MEMBERS Project Leader: Terry Gimbel, Colorado State Parks Final content editing 2005 Edition: Pamela Packer, COTI 2006 Edition: Hugh Duffy and Hugh Osborne, National Park Service; Mick Syzek, Continental Divide Trail Alliance Alice Freese, Colorado Outdoor Training Initiative Scott Gordon, Bicycle Colorado Sarah Gorecki, Colorado Fourteeners Initiative Jon Halverson, USFS-Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest David Hirt, Boulder County -

Town of Woodstock, New York Master Plan

PREPARED FOR: T OWN OF W OODSTOCK, NEW Y ORK PREPARED BY: W OODSTOCK C OMPREHENSIVE P LANNING C OMMITTEE D ALE H UGHES, CHAIR R ICHARD A. ANTHONY J OSEPH A. DAIDONE D AVID C. EKROTH J ON L EWIS J OAN L ONEGRAN J ANINE M OWER E LIZABETH R EICHHELD J EAN W HITE A ND T HE S ARATOGA A SSOCIATES Landscape Architects, Architects, Engineers, and Planners, P.C. Saratoga Springs New York Boston This document was made possible with funds from New York State Department of State Division of Local Government and the New York State Planning Federation Rural New York Grant Program THE SARATOGA ASSOCIATES. All Rights Reserved T HE T OWN OF W OODSTOCK C OMPREHENSIVE P LANNING C OMMITTEE AND THE T OWN B OARD WOULD LIKE TO EXTEND A SPECIAL THANKS TO ALL THE VOLUNTEERS WHO ASSISTED WITH THE PREPARATION OF THE PLAN. E SPECIALLY: J ERRY W ASHINGTON AND B OBBIE C OOPER FOR THEIR ASSITANCE ON THE C OMMUNITY S URVEY TABLE OF CONTENTS April 2003 TOWN OF WOODSTOCK COMPREHENSIVE PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Bound under separate cover) I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. A COMPREHENSIVE PLAN FOR WOODSTOCK 1 B. THE COMMUNITY PLANNING PROCESS 2 C. PUBLIC INPUT 3 D. DEVELOPING A PLANNING APPROACH FOR WOODSTOCK 9 II. INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS 12 A. REGIONAL SETTING AND HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 12 B. EXISTING LAND USE 14 C. DEMOGRAPHIC & ECONOMIC TRENDS 19 D. HOUSING & NEIGHBORHOODS 29 E. RECREATIONAL FACILITIES 34 F. RELIGIOUS / SPIRITUAL ORGANIZATIONS 37 G. ARTS AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATIONS 37 H. ENVIRONMENTAL FEATURES 38 BUILD-OUT ANALYSIS 52 I. -

The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association a Portfolio

The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association A Portfolio Woodstock Artists Association Gallery, c. 1920s. Courtesy W.A.A. Archives. Photo: Stowall Studio. Carl Eric Lindin (1869-1942), In the Ojai, 1916. Oil on Board, 73/4 x 93/4. From the Collection of the Woodstock Library Association, gift of Judy Lund and Theodore Wassmer. Photo: Benson Caswell. Henry Lee McFee (1886- 1953), Glass Jar with Summer Squash, 1919. Oil on Canvas, 24 x 20. Woodstock Artists Association Permanent Collection, gift of Susan Braun. Photo: John Kleinhans. Andrew Dasburg (1827-1979), Adobe Village, c. 1926. Oil on Canvas, 19 ~ x 23 ~ . Private Collection. Photo: Benson Caswell. John F. Carlson (1875-1945), Autumn in the Hills, 1927. Oil on Canvas, 30 x 60. 'Geenwich Art Gallery, Greenwich, Connecticut. Photo: John Kleinhans. Frank Swift Chase (1886-1958), Catskills at Woodstock, c. 1928. Oil on Canvas, 22 ~ x 28. Morgan Anderson Consulting, N.Y.C. Photo: Benson Caswell. The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association Tom Wolf The Woodstock Artists Association has been showing the work of artists from the Woodstock area for eighty years. At its inception, many people helped in the work involved: creating a corporation, erecting a building, and develop ing an exhibition program. But traditionally five painters are given credit for the actual founding of the organization: John Carlson, Frank Swift Chase, Andrew Dasburg, Carl Eric Lindin, and Henry Lee McFee. The practice of singling out these five from all who participated reflects their extensive activity on behalf of the project, and it descends from the writer Richard Le Gallienne. -

The Wheeler Family of Rutland, Mass

The Wheeler Family of Rutland, Mass. and Some of Their Ancestors By Daniel M. Wheeler Member American Society of Cn'il Engineen TO THE MEMORY OF MY ANCESTORS WHOSE NOBLE AND UPRIGHT-LIVES HAVE MADE RESPECTED THE NAME OF WHEELER AND WHOSE VIRTUES I WOULD TRANSMIT TO FUTURE GENERATIONS. THIS VOLUME IS REVERENTLY DEDICATED r I I WHEELER HOMESTEAD, RUTLAND, MASS. (From Top of \Vater \Vorks Tower) INTRODUCTORY How little we know concerning our ancestors, even of those who have immediately preceded us. :n the words of another, "Aye thus it is, one generation comes, Another goes and mingles with the dust. And thus we come and go and come and go Each for a little moment filling up Some little place-and thus we disappear In quick succession and it shall be so Till time in one vast perpetuity Be swallowed up." Most of us reach n1iddle life before we interest ourselves in matters pertaining to our ancestors and it is then too late to avail ourselves of the information that we might have acquired of our elders in our early life. Having been able during the past twenty-five years to devote some odd hours to the study .of his ancestors, the author deems it his duty as well as his privilege to put upon record the facts that he has learned and here with presents them with the hope that they may be of some service to posterity. Daniel Webster is reported to have said, "It is wise for us to recur to the history of our ancestors those who do not look upon thems~lves as a link connecting the past with the future, do not perform their duty to the world." The author is not so foolish as to claim that there are no errors to be found in this volume but he trusts that if errors are found the finder will charitably consider how great and how difficult has been the task of in vestigation and compilation extending through many years and involving the searching of hundreds of records widely scattered. -

March 2007 No. 126 Chaff from the President

The Disp ays from Chat+anooga page 4 I Committee ~eports page 6 fo Raise Children's Confidence, Teach page 10 Collection Spotlight page ~ 2 Update for Stanley No. 120 Block Plane page • 8 Stanley No. 164 Low Angle Block P1are page 26 I M-WTCA Auxiliary page 30 A Pub · cation of the M" d-West Tool Col ectors Association What's It page 35 M-WTCA.ORG Teaching Children About 'lbols story begin:::; on page 10 March 2007 No. 126 Chaff From The President Its spring and time to think about the your horizons by taking in the architecture, art, all the things you and your partner decorative arts, and fine food. Make some new friends, can do to maximize your enjoyment and share experiences with old friends along the way. and the fun you can have in the wonderful world of tool collecting. Hopefully you travel together and share the fun of visiting new places, and experiencing the wonders the world has to offer. Perhaps you enjoy seeing the magnificent creations in architecture, sculpture, and painting produced in different places and during different historical periods. Perhaps you prefer the decorative arts, furniture, textiles, and smaller artifacts, such as tools of the many trades and crafts, which have been refined and perfected over centuries to improve our way of life. Along the way you might enjoy an occasional meal in a splendid It might also be a good time to re-evaluate your restaurant that serves marvelous cuisine. Whatever collection. Have your interests changed? Do you need your tastes, it is the fun of doing it, and the overall to refocus, improve the way your collection is displayed, broadening of your experience of life that matters. -

Hudson River Valley

Hudson River Valley 17th Annual Ramble SEPTEMBER 3-25, 2016 WALK, HIKE, PADDLE, BIKE & TOUR HudsonRiverValleyRamble.com #HudsonRamble A Celebration of the Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Hudson River Estuary Program, and New York State Parks and Historic Sites B:8.4375" T:8.1875" S:7" There’s New York and then there’s New York Traveling through Stewart International Airport is the easiest way to take full advantage of the Hudson Valley’s astounding B:11.125" T:10.875" natural beauty and historic S:10" attractions. In addition to off ering hassle-free boarding, on-time performance and aff ordable fares on Allegiant, American, Delta and JetBlue, we’re also just a short drive from New York City. So, to make the most of your time in the Hudson Valley, fl y into Stewart. And begin exploring. Stewart International Airport JOB: POR-A01-M00808E DOCUMENT NAME: 6E79822_POR_a2.1_sk.indd DESCRIPTION: SWF Destinations of NY Tourism ad BLEED: 8.4375" x 11.125" TRIM: 8.1875" x 10.875" SAFETY: 7" x 10" GUTTER: None PUBLICATION: Westchester Official Travel & Meeting Guide ART DIRECTOR: COPYWRITER: ACCT. MGR.: Basem Ebied 8-3291 ART PRODUCER: PRINT PROD.: Peter Herbsman 8-3725 PROJ. MNGR.: None This advertisement prepared by Young & Rubicam, N.Y. 6E79822_POR_a2.1_sk.indd CLIENT: PANYNJ TMG #: 6E79822 HANDLE #: 2 JOB #: POR-A01-M00808E BILLING#: POR-A01-M00808 DOCUMENT NAME: 6E79822_POR_a2.1_sk.indd PAGE COUNT: 1 of 1 PRINT SCALE: None INDESIGN VERSION: CC 2015 STUDIO ARTIST: steven -

Catskill Watershed Corporation Annual Report 2019

Catskill Watershed Corporation Annual Report 2019 Our Neighborhood The Catskill Watershed Corporation’s environ- mental protection, economic development and education programs are conducted in 41 towns that lie wholly or partially within the NYC Cats- kill-Delaware Watershed region which supplies water to 9.5 million people in New York City and four upstate counties. 2 Arrivals and Departures he CWC welcomed a new Board member and said farewell to a long time Direc- tor. Mark McCarthy, left, former Supervisor of Neversink, Sullivan County Legisla- tor and a member of the CWC Board for the past five years stepped down following the CWC Annual Meeting April 2, 2019. Chris Mathews, current Supervisor for the Town of Neversink was elected to fill Mark’s seat. Mark McCarthy Christopher Mathews Cambria Tallman Skylie Roberts he CWC added two staff members to the next generation of Watershed Stewards: Cambria Tallman as Administrative Assistant and Skylie Roberts as Bookkeeper. Kimberlie Ackerley Diane Galusha Leo LaBuda Wendy Loper e bid farewell to several long-time CWC staff members. Kimberlie Ackerley, Program Specialist— Stormwater; Diane Galusha, Public Education Direc- tor; Leo LaBuda, Environmental Engineering Spe- cialist; and Wendy Loper, Bookkeeper all departed after many years of valued service. 3 A Message from the Executive Director 019 was a very remarkable year for CWC. 2019 marked 23 years of service for the organization. Our dedicated staff has done an incredible job at reorganizing while strengthening our programs and services. The new office building will increase the value of services delivered directly to Watershed residents, businesses and users of the water supply. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating' adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

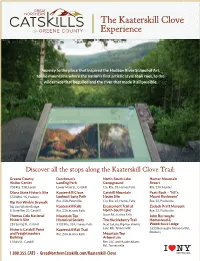

The Kaaterskill Clove Experience

The Kaaterskill Clove Experience Journey to the place that inspired the Hudson River School of Art, to the mountains where the nation’s fi rst artistic style took root, to the wilderness that beguiled and the river that made it all possible. Discover all the stops along the Kaaterskill Clove Trail: Greene County Dutchman’s North-South Lake Hunter Mountain Visitor Center Landing Park Campground Resort 700 Rte. 23B, Leeds Lower Main St., Catskill Cty. Rte. 18, Haines Falls Rte. 23A, Hunter Olana State Historic Site Kaaterskill Clove Catskill Mountain Pratt Rock – “NY’s 5720 Rte. 9G, Hudson Lookout/Long Path House Site Mount Rushmore” Rip Van Winkle Skywalk Rte. 23A, Palenville Cty. Rte. 18, Haines Falls Rte. 23, Prattsville Rip Van Winkle Bridge Kaaterskill Falls Escarpment Trail at Zadock Pratt Museum & State Rte. 23, Catskill Rte. 23A, Haines Falls North-South Lake Rte. 23, Prattsville Thomas Cole National Mountain Top Scutt Rd., Haines Falls John Burroughs Historic Site Historical Society The Huckleberry Trail Homestead & 218 Spring St., Catskill 5132 Rte. 23A, Haines Falls Next to Lake Rip Van Winkle Woodchuck Lodge Historic Catskill Point Kaaterskill Rail Trail Lake Rd., Tannersville 1633 Burroughs Memorial Rd., Roxbury and Freightmasters Rte. 23A, Haines Falls Mountain Top Building Arboretum 1 Main St., Catskill Rte. 23C and Maude Adams Rd., Tannersville 1.800.355.CATS • GreatNorthernCatskills.com/Kaaterskill-Clove Travel a new path through America’s rst wilderness – Take a self-guided, set-your-own pace journey through history. Greene County Visitor Center Kaaterskill Clove Lookout/ Catskill Mountain House Site Start the trail at the Greene County Long Path Proceed through the North-South Lake Visitor Center located at Exit 21 off the Follow Main Street west to the traffi c light Campground entrance (see previous NYS Thruway (I-87) and stop in to get and make a left onto Bridge Street. -

The Making of David Mccosh Early Paintings, Drawings, and Prints

The Making of DaviD Mccosh early Paintings, Drawings, and Prints Policeman, n.d. Charcoal and graphite on paper, 11 x 8 ½ inches David John McCosh Memorial Collection The Prodigal Son, 1927 Oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 40 3/4 inches Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Museum purchase. 28.1 8 The makIng of davId mcCosh danielle m. knapp In 1977, David and Anne McCosh participated in an oral history interview conducted by family friend Phil Gilmore.1 During the course of the interview the couple reminisced about the earliest years of their careers and the circumstances that had brought them to Eugene, Oregon, in 1934. As the three discussed the challenges of assessing one’s own oeuvre, Anne emphatically declared that “a real retrospective will show the first things you ever exhibited.” In David’s case, these “first things” were oil paintings, watercolors, and lithographs created during his student years at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) and as a young struggling artist in the Midwest and New York and at several artist colonies and residencies. This exhibition, The Making of David McCosh: Early Paintings, Drawings, and Prints, highlights those years of his life with dual purpose: to thoughtfully examine his body of work from the 1920s and early ’30s and to provide those familiar with his celebrated later work a more complete understanding of the entire arc of this extraordinary artist’s career. McCosh’s output has always defied traditional categorization within art historical styles. During his life he found strict allegiance to stylistic perimeters to be, at best, distracting and, at worse, repressive, though his own work certainly reflected elements of the artistic communities through which he moved. -

The Finding Aid to the Alf Evers Archive

FINDING AID TO THE ALF EVERS’ ARCHIVE A Account books & Ledgers Ledger, dark brown with leather-bound spine, 13 ¼ x 8 ½”: in front, 15 pp. of minutes in pen & ink of meetings of officers of Oriental Manufacturing Co., Ltd., dating from 8/9/1898 to 9/15/1899, from its incorporation to the company’s sale; in back, 42 pp. in pencil, lists of proverbs; also 2 pages of proverbs in pencil following the minutes Notebook, 7 ½ x 6”, sold by C.W. & R.A. Chipp, Kingston, N.Y.: 20 pp. of charges & payments for goods, 1841-52 (fragile) 20 unbound pages, 6 x 4”, c. 1837, Bastion Place(?), listing of charges, payments by patrons (Jacob Bonesteel, William Britt, Andrew Britt, Nicolas Britt, George Eighmey, William H. Hendricks, Shultis mentioned) Ledger, tan leather- bound, 6 ¾ x 4”, labeled “Kingston Route”, c. 1866: misc. scattered notations Notebook with ledger entries, brown cardboard, 8 x 6 ¼”, missing back cover, names & charges throughout; page 1 has pasted illustration over entries, pp. 6-7 pasted paragraphs & poems, p. 6 from back, pasted prayer; p. 23 from back, pasted poems, pp. 34-35 from back, pasted story, “The Departed,” 1831-c.1842 Notebook, cat. no. 2004.001.0937/2036, 5 1/8 x 3 ¼”, inscr. back of front cover “March 13, 1885, Charles Hoyt’s book”(?) (only a few pages have entries; appear to be personal financial entries) Accounts – Shops & Stores – see file under Glass-making c. 1853 Adams, Arthur G., letter, 1973 Adirondack Mountains Advertisements Alderfer, Doug and Judy Alexander, William, 1726-1783 Altenau, H., see Saugerties, Population History files American Revolution Typescript by AE: list of Woodstock residents who served in armed forces during the Revolution & lived in Woodstock before and after the Revolution Photocopy, “Three Cemeteries of the Wynkoop Family,” N.Y.