U.S. Civilian Space Policy Priorities and the Implication of Those Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Commission on the Scientific Case for Human Space Exploration

1 ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY Burlington House, Piccadilly London W1J 0BQ, UK T: 020 7734 4582/ 3307 F: 020 7494 0166 [email protected] www.ras.org.uk Registered Charity 226545 Report of the Commission on the Scientific Case for Human Space Exploration Professor Frank Close, OBE Dr John Dudeney, OBE Professor Ken Pounds, CBE FRS 2 Contents (A) Executive Summary 3 (B) The Formation and Membership of the Commission 6 (C) The Terms of Reference 7 (D) Summary of the activities/meetings of the Commission 8 (E) The need for a wider context 8 (E1) The Wider Science Context (E2) Public inspiration, outreach and educational Context (E3) The Commercial/Industrial context (E4) The Political and International context. (F) Planetary Science on the Moon & Mars 13 (G) Astronomy from the Moon 15 (H) Human or Robotic Explorers 15 (I) Costs and Funding issues 19 (J) The Technological Challenge 20 (J1) Launcher Capabilities (J2) Radiation (K) Summary 23 (L) Acknowledgements 23 (M) Appendices: Appendix 1 Expert witnesses consulted & contributions received 24 Appendix 2 Poll of UK Astronomers 25 Appendix 3 Poll of Public Attitudes 26 Appendix 4 Selected Web Sites 27 3 (A) Executive Summary 1. Scientific missions to the Moon and Mars will address questions of profound interest to the human race. These include: the origins and history of the solar system; whether life is unique to Earth; and how life on Earth began. If our close neighbour, Mars, is found to be devoid of life, important lessons may be learned regarding the future of our own planet. 2. While the exploration of the Moon and Mars can and is being addressed by unmanned missions we have concluded that the capabilities of robotic spacecraft will fall well short of those of human explorers for the foreseeable future. -

Supportability for Beyond Low Earth Orbit Missions

Supportability for Beyond Low Earth Orbit Missions William Cirillo1 and Kandyce Goodliff2 NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, VA, 23681 Gordon Aaseng3 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, 94035 Chel Stromgren4 Binera, Inc., Silver Springs, MD, 20910 and Andrew Maxwell5 Georgia Institute of Technology, Hampton, VA 23666 Exploration beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO) presents many unique challenges that will require changes from current Supportability approaches. Currently, the International Space Station (ISS) is supported and maintained through a series of preplanned resupply flights, on which spare parts, including some large, heavy Orbital Replacement Units (ORUs), are delivered to the ISS. The Space Shuttle system provided for a robust capability to return failed components to Earth for detailed examination and potential repair. Additionally, as components fail and spares are not already on-orbit, there is flexibility in the transportation system to deliver those required replacement parts to ISS on a near term basis. A similar concept of operation will not be feasible for beyond LEO exploration. The mass and volume constraints of the transportation system and long envisioned mission durations could make it difficult to manifest necessary spares. The supply of on-demand spare parts for missions beyond LEO will be very limited or even non-existent. In addition, the remote nature of the mission, the design of the spacecraft, and the limitations on crew capabilities will all make it more difficult to maintain the spacecraft. Alternate concepts of operation must be explored in which required spare parts, materials, and tools are made available to make repairs; the locations of the failures are accessible; and the information needed to conduct repairs is available to the crew. -

Russia's Posture in Space

Russia’s Posture in Space: Prospects for Europe Executive Summary Prepared by the European Space Policy Institute Marco ALIBERTI Ksenia LISITSYNA May 2018 Table of Contents Background and Research Objectives ........................................................................................ 1 Domestic Developments in Russia’s Space Programme ............................................................ 2 Russia’s International Space Posture ......................................................................................... 4 Prospects for Europe .................................................................................................................. 5 Background and Research Objectives For the 50th anniversary of the launch of Sputnik-1, in 2007, the rebirth of Russian space activities appeared well on its way. After the decade-long crisis of the 1990s, the country’s political leadership guided by President Putin gave new impetus to the development of national space activities and put the sector back among the top priorities of Moscow’s domestic and foreign policy agenda. Supported by the progressive recovery of Russia’s economy, renewed political stability, and an improving external environment, Russia re-asserted strong ambitions and the resolve to regain its original position on the international scene. Towards this, several major space programmes were adopted, including the Federal Space Programme 2006-2015, the Federal Target Programme on the development of Russian cosmodromes, and the Federal Target Programme on the redeployment of GLONASS. This renewed commitment to the development of space activities was duly reflected in a sharp increase in the country’s launch rate and space budget throughout the decade. Thanks to the funds made available by flourishing energy exports, Russia’s space expenditure continued to grow even in the midst of the global financial crisis. Besides new programmes and increased funding, the spectrum of activities was also widened to encompass a new focus on space applications and commercial products. -

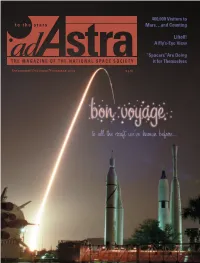

To All the Craft We've Known Before

400,000 Visitors to Mars…and Counting Liftoff! A Fly’s-Eye View “Spacers”Are Doing it for Themselves September/October/November 2003 $4.95 to all the craft we’ve known before... 23rd International Space Development Conference ISDC 2004 “Settling the Space Frontier” Presented by the National Space Society May 27-31, 2004 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Location: Clarion Meridian Hotel & Convention Center 737 S. Meridian, Oklahoma City, OK 73108 (405) 942-8511 Room rate: $65 + tax, 1-4 people Planned Programming Tracks Include: Spaceport Issues Symposium • Space Education Symposium • “Space 101” Advanced Propulsion & Technology • Space Health & Biology • Commercial Space/Financing Space Space & National Defense • Frontier America & the Space Frontier • Solar System Resources Space Advocacy & Chapter Projects • Space Law and Policy Planned Tours include: Cosmosphere Space Museum, Hutchinson, KS (all day Thursday, May 27), with Max Ary Oklahoma Spaceport, courtesy of Oklahoma Space Industry Development Authority Oklahoma City National Memorial (Murrah Building bombing memorial) Omniplex Museum Complex (includes planetarium, space & science museums) Look for updates on line at www.nss.org or www.nsschapters.org starting in the fall of 2003. detach here ISDC 2004 Advance Registration Form Return this form with your payment to: National Space Society-ISDC 2004, 600 Pennsylvania Ave. S.E., Suite 201, Washington DC 20003 Adults: #______ x $______.___ Seniors/Students: #______ x $______.___ Voluntary contribution to help fund 2004 awards $______.___ Adult rates (one banquet included): $90 by 12/31/03; $125 by 5/1/04; $150 at the door. Seniors(65+)/Students (one banquet included): $80 by 12/31/03; $100 by 5/1/04; $125 at the door. -

Race to Space Educator Edition

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grade Level RACE TO SPACE 10-11 Key Topic Instructional Objectives U.S. space efforts from Students will 1957 - 1969 • analyze primary and secondary source documents to be used as Degree of Difficulty supporting evidence; Moderate • incorporate outside information (information learned in the study of the course) as additional support; and Teacher Prep Time • write a well-developed argument that answers the document-based 2 hours essay question regarding the analogy between the Race to Space and the Cold War. Problem Duration 60 minutes: Degree of Difficulty -15 minute document analysis For the average AP US History student the problem may be at a moderate - 45 minute essay writing difficulty level. -------------------------------- Background AP Course Topics This problem is part of a series of Social Studies problems celebrating the - The United States and contributions of NASA’s Apollo Program. the Early Cold War - The 1950’s On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy spoke before a special joint - The Turbulent 1960’s session of Congress and challenged the country to safely send and return an American to the Moon before the end of the decade. President NCSS Social Studies Kennedy’s vision for the three-year old National Aeronautics and Space Standards Administration (NASA) motivated the United States to develop enormous - Time, Continuity technological capabilities and inspired the nation to reach new heights. and Change Eight years after Kennedy’s speech, NASA’s Apollo program successfully - People, Places and met the president’s challenge. On July 20, 1969, the world witnessed one of Environments the most astounding technological achievements in the 20th century. -

The Space Race

The Space Race Aims: To arrange the key events of the “Space Race” in chronological order. To decide which country won the Space Race. Space – the Final Frontier “Space” is everything Atmosphere that exists outside of our planet’s atmosphere. The atmosphere is the layer of Earth gas which surrounds our planet. Without it, none of us would be able to breathe! Space The sun is a star which is orbited (circled) by a system of planets. Earth is the third planet from the sun. There are nine planets in our solar system. How many of the other eight can you name? Neptune Saturn Mars Venus SUN Pluto Uranus Jupiter EARTH Mercury What has this got to do with the COLD WAR? Another element of the Cold War was the race to control the final frontier – outer space! Why do you think this would be so important? The Space Race was considered important because it showed the world which country had the best science, technology, and economic system. It would prove which country was the greatest of the superpowers, the USSR or the USA, and which political system was the best – communism or capitalism. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xvaEvCNZymo The Space Race – key events Discuss the following slides in your groups. For each slide, try to agree on: • which of the three options is correct • whether this was an achievement of the Soviet Union (USSR) or the Americans (USA). When did humans first send a satellite into orbit around the Earth? 1940s, 1950s or 1960s? Sputnik 1 was launched in October 1957. -

Science in Nasa's Vision for Space Exploration

SCIENCE IN NASA’S VISION FOR SPACE EXPLORATION SCIENCE IN NASA’S VISION FOR SPACE EXPLORATION Committee on the Scientific Context for Space Exploration Space Studies Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. Support for this project was provided by Contract NASW 01001 between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors. International Standard Book Number 0-309-09593-X (Book) International Standard Book Number 0-309-54880-2 (PDF) Copies of this report are available free of charge from Space Studies Board National Research Council The Keck Center of the National Academies 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu. Copyright 2005 by the National Academy of Sciences. -

State of Space 2020 Remarks by Tom Zelibor, CEO Space Foundation February 11, 2020 National Press Club, Washington, DC

State of Space 2020 Remarks by Tom Zelibor, CEO Space Foundation February 11, 2020 National Press Club, Washington, DC [As prepared for delivery] There has never been a better time to be in the space community. Even though we just celebrated the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 last summer, the next 50 years will be even more exciting and transformational for all of us. The same excitement I felt as a 15-year-old sitting on my parents living room floor watching Neil and Buzz making history is back again. So, we should ask ourselves, what will be different this time? • This is not just a US government endeavor...it will encompass all aspects of our space ecosystem. • It will not be a group of scientists and engineers that look like me...it will be a diverse, multi-racial, all gender, multi-generational team all dedicated to a common mission. • It will not be the East vs. West space race between two superpowers...it will be a worldwide endeavor that brings the best and the brightest talent of all nations to make the next great human adventure to space even better than the last. • Finally, it will have a heavy component of public-private partnerships to leverage the best we all have to offer. So, what were some of the exciting events that took place in 2019? 1. Creation of Space Force (December) 2. Vice President Pence announced the goal of NASA returning to the Moon by 2024; Project Artemis was announced and kicked off. (March) 1 3. Virgin Galactic IPO is offered (October) – creating market value of over $2 billion 4. -

United States Space Foundation (NASA-CR-194836) SPACE TECHNOLOGY: N94-23526 a STUDY of the SIGNIFICANCE of RECOGNITION for INNOVATORS of SPINUFF TECHNOLOGIES

United States Space Foundation (NASA-CR-194836) SPACE TECHNOLOGY: N94-23526 A STUDY OF THE SIGNIFICANCE OF RECOGNITION FOR INNOVATORS OF SPINUFF TECHNOLOGIES. 1993 Uncl as ACTIVITIES/1994, 1995 PLANS Annual Report (Space Foundation) 31 p 63/85 0202105 Space Technology - A Study of the Significance of Recognition for Innovators of Spinoff Technologies Annual Report 1993 Activities/ 1994, 1995 Plans NASA Grant NAGW-3322 January 1994 2860 S. Circle Drive, Suite 2301 ,Colorado S rings, CO 80906 Telephone: (719) 57 88000 FAX: (719) 576-8801 Space Technology--A Study of the Significance of Recognition for Innovators of Spinoff Technologies .- (NASA Grant NAGW-3322) I I 1993 Activities/l994, 1995 Plans During the past 30 years as NASA has conducted technology transfer programs, it has gained considerable experience--particularly pertaining to the processes. However, three areas have not had much scrutiny: the examination of the contributions of the individuals who have developed successhl spinoffs; the commercial success of the spinoffs themselves; and the degree to which they are understood by the public. In short, there has been limited evaluation to measure the success of technology transfer efforts mandated by Congress. Research conducted during the first year of a three-year NASA grant to the United States Space Foundation has taken the initial steps toward measuring the success of methodologies to accomplish that Congressionally-mandated technology transfer. In particular, the US Space Foundation, in cooperation with ARAC, technology transfer experts; JKA, a nationally recognized themed entertainment design company; and top evaluation consultants, has inaugurated and evaluated a fresh approach including commercial practices to encourage, motivate, and energize technology transfer by .. -

The American Space Exploration Narrative from the Cold War Through the Obama Administration1

The American Space Exploration Narrative from the Cold War through the Obama Administration1 Dora Holland2,3 and Jack O. Burns4,5 1 To appear in the journal Space Policy. 2 International Affairs Program, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309 3 Current mailing address: 11161 Briggs Court, Anchorage, AK, 99516. 4 Center for Astrophysics & Space Astronomy, Department of Astrophysical & Planetary Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309 5 Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (D. Holland), [email protected] (J. Burns) 2 Abstract We document how the narrative and the policies of space exploration in the United States have changed from the Eisenhower through the Obama administrations. We first examine the history of U.S. space exploration and also assess three current conditions of the field of space exploration including: 1) the increasing role of the private sector, 2) the influence of global politics and specifically the emergence of China as a global space power, and 3) the focus on a human mission to Mars. In order to further understand the narrative of U.S. space exploration, we identify five rhetorical themes: competition, prestige, collaboration, leadership, and “a new paradigm.” These themes are then utilized to analyze the content of forty documents over the course of space exploration history in the U.S. from eight U.S. presidential administrations. The historical narrative and content analysis together suggest that space exploration has developed from a discourse about a bipolar world comprised of the United States and the Soviet Union into a complicated field that encompasses many new players in the national to the industrial realms. -

Repair Station Capabilities List

Approved by: Astronautics Corporation of America J. Simet, Repair Station Supervisor Approved by: TITLE: Astronautics Corp. of America Repair Station Capabilities List QAP 2003/2 REV. H J. Williams, Repair Station Accountable Manager CODE IDENT NO 10138 Page 1 of 35 Astronautics’ Capabilities List QAP 2003/2 Revision H QAP 2003/2 Astronautics Corporation of America REV SYM DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE DATE APPROVED A Initial Release. 3/25/2003 PFM B Updated to reflect FAA comments regarding when revisions will 1/16/2004 JT, DY, JGW be submitted. C Updated to change the preliminary XQAR449-P-L Repair 6/25/2004 JT, EF, JGW Station Number to XQAR449L. Added the 197800-1 & -3 DU, the 198200-1 & -3 EU, the 198000-( ) EFI and its 198040-( ) Control Panel, and the 260500-( ) EFI. App Added the PMA’d 197800-1 and -3 Display Unit, the 198200-1 6/25/2004 JGW A and -3 Electronics Unit, and the TSOA’d 198000-( ) EFI and its 198040-( ) Control Panel, and the 260500-( ) EFI. The self- evaluation for these items was performed under paragraph 5.5 (d) of this document. These FAA approvals were the basis for the additions. D Updated to separate Appendix A from the text (removed the date 11/30/2004 JT, EF, JGW on the cover sheet for the Appendix). The FAA will be sent a copy of the Appendix within ten days of the date on the Appendix whenever items are added or removed. The appendix will be controlled by date. A copy of the QAP cover sheet and text are controlled by revision letter, and a copy of that will be submitted to the FAA within ten days of the date that the new revision letter version of the text is released. -

The Ethics of Animal Research – Teacher Notes

The Ethics of Animal Research – Teacher Notes The previous lesson showed the extensive use of animals in the early days of space research and even today to further our understanding of the space environment. This raises important questions about the ethics of using animals in research. The use of animals in scientific experimentation has always been, and will always be a controversial subject. It is however an unavoidable fact that without animal research we would know far less about biology, diseases and medical conditions that affect humans and other animals. While researchers agree that animals should only be used when there is no known alternative and they should be treated with humane respect to avoid suffering, the scientific community continue to agree that the historical use of animals in research has allowed the development of medical treatment, surgical techniques, vaccines and the advancement of science in other areas. As we know animals were used extensively to serve as surrogates for human beings in the early days of spaceflight to learn vital information about the environment. In recent times, although animals continue to be used in space research, valid arguments about animal suffering have led to great improvements in their treatment. It is estimated that between 50 and 100 million animals are used in research experiments every year. Animals used in testing come from a variety of sources. While many animals, particularly worms and rats, may be purpose bred for testing other animals are still caught in the wild. Opponents to animal testing argue that it is cruel and unnecessary, that the results never reliably predict the reaction of human physiology and that animals have the same right as humans not to be used for experimentation.