Homospory 2002: an Odyssey of Progress in Pteridophyte Genetics And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Department Botany

THE HISTORY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY 1889-1989 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA SHERI L. BARTLETT I - ._-------------------- THE HISTORY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY 1889-1989 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA SHERI L. BARTLETT TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1-11 Chapter One: 1889-1916 1-18 Chapter Two: 1917-1935 19-38 Chapter Three: 1936-1954 39-58 Chapter Four: 1955-1973 59-75 Epilogue 76-82 Appendix 83-92 Bibliography 93-94 -------------------------------------- Preface (formerly the College of Science, Literature and the Arts), the College of Agriculture, or The history that follows is the result some other area. Eventually these questions of months ofresearch into the lives and work were resolved in 1965 when the Department of the Botany Department's faculty members joined the newly established College of and administrators. The one-hundred year Biological Sciences (CBS). In 1988, The overview focuses on the Department as a Department of Botany was renamed the whole, and the decisions that Department Department of Plant Biology, and Irwin leaders made to move the field of botany at Rubenstein from the Department of Genetics the University of Minnesota forward in a and Cell Biology became Plant Biology's dynamic and purposeful manner. However, new head. The Department now has this is not an effort to prove that the administrative ties to both the College of Department's history was linear, moving Biological Sciences and the College of forward in a pre-determined, organized Agriculture. fashion at every moment. Rather I have I have tried to recognize the attempted to demonstrate the complexities of accomplishments and individuality of the the personalities and situations that shaped Botany Department's faculty while striving to the growth ofthe Department and made it the describe the Department as one entity. -

CAPITAL DISTRICT GROWING TRENDS Volume 19, Issue 9

CAPITAL DISTRICT GROWING TRENDS Volume 19, Issue 9 Lily Calderwood to join CAAHP Team The Capital Area Agriculture and Horticulture Program is pleased to announce that Lily Calderwood will join the team as Senior Commercial Horticulture Educator on January 19, 2016. Lily recently received her PhD in Plant and Soil Science from the University of Vermont, where she studied integrated pest management (IPM) tools for hop production in the northeast. She is currently an IPM Specialist working as a member of the UVM Extension Northwest Crops and Soils Team. Lily has strived to develop sustainable and practical IPM practices for locally produced hops, dry beans, wheat, and barley. Lily comes to CAAHP with an ecology background, a passion for sustainable agriculture and an interest in growers’ needs. She is excited to learn about the commercial horticulture industries in the Capital Area, to listen to grower challenges, and to work collaboratively to develop a research and outreach program. In This Issue: Lily Calderwood Joins the CAAHP Team! Capital District Bedding Plant Nurserymen's Education Day Topping Trees Is Not Proper Pruning Overwintering Plants In The Landscape Fabulous Ferns! Topping Trees Is Not Proper Pruning - Chuck Schmitt Think before you top your tree... Homeowners often feel that their trees have become too large and now pose a hazard to their house or other structures, so they have their trees topped, believing this will not only reduce the tree's size but that it will also decrease potential hazards. What they do not realize is that though they now have a smaller tree, it is probably a greater hazard than before it was cut. -

Floral Symmetry Affects Speciation Rates in Angiosperms Risa D

Received 25 July 2003 Accepted 13 November 2003 Published online 16 February 2004 Floral symmetry affects speciation rates in angiosperms Risa D. Sargent Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Boulevard, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada ([email protected]) Despite much recent activity in the field of pollination biology, the extent to which animal pollinators drive the formation of new angiosperm species remains unresolved. One problem has been identifying floral adaptations that promote reproductive isolation. The evolution of a bilaterally symmetrical corolla restricts the direction of approach and movement of pollinators on and between flowers. Restricting pollin- ators to approaching a flower from a single direction facilitates specific placement of pollen on the pollin- ator. When coupled with pollinator constancy, precise pollen placement can increase the probability that pollen grains reach a compatible stigma. This has the potential to generate reproductive isolation between species, because mutations that cause changes in the placement of pollen on the pollinator may decrease gene flow between incipient species. I predict that animal-pollinated lineages that possess bilaterally sym- metrical flowers should have higher speciation rates than lineages possessing radially symmetrical flowers. Using sister-group comparisons I demonstrate that bilaterally symmetric lineages tend to be more species rich than their radially symmetrical sister lineages. This study supports an important role for pollinator- mediated speciation and demonstrates that floral morphology plays a key role in angiosperm speciation. Keywords: reproductive isolation; pollination; sister group comparison; zygomorphy 1. INTRODUCTION The importance of pollinator-mediated selection in angiosperms is well supported by theory (Kiester et al. -

General Botany Lab Review Fungi, Algae, Bryophytes, Ferns & Fern Allies

General Botany Lab Review Fungi, Algae, Bryophytes, Ferns & Fern Allies You have looked at a lot of stuff – both live and via prepared slides. You’ve also labeled at least one Life Cycle Diagram for each of the groups. Know what your benchmarks are for a general life cycle diagram and be able to label them. I will not ask you to identify anything to species or genus; be able to identify things to “group” (i.e., ascomycete, bryophyta, etc.) Be able to identify growth form (e.g., unicell, filamentous, etc.). Recognize the differences between sexual and asexual reroductive structures. All questions will be multiple choice. Material looked at: UNIT 1: FUNGI EXERCISE 1: CHYTRIDS/ CHYTRIDOMYCOTA: Allmyces arbusculus – life and prepared slides EXERCISE 2: ZYGOMYCETES/ ZYGOMYCOTA: Rhizopus stolonifer – live and prepared slides EXERCISE 2: MYCORRHIZA and the GLOMEROMYCETES/ GLOMEROMYCOTA – prepared slides only EXERCISE 3: ASCOMYCETES/ ASCOMYCOTA Aspergillus sp., Penicillium sp., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Peziza sp., Sordaria fimicola, and Morchella sp. – a mixture of live and prepared materials EXERCISE 4: BASIDIOMYCETES/BASIDIOMYCETES Agaricus, Coprinus, Cronartium (a rust), Ustilago (a smut) – slides, fresh, and dried EXERCISE 5: SLIME MOLDS – live and prepared Physarum EXERCISE 6: LICHENS – live and prepared slides be able to identify the various growth forms UNIT 2: ALGAE EXERCISE 1: CYANOBACTERIA Anabaena sp., Nostoc, and Oscillaroria – live and prepared material EXERCISE 2: SUPERGROUP EXCAVATA (Phylum Euglenophyta) – live and prepared material -

XI MOBILE NO:9340839715 CHAPTER-3 Plant Kingd

NAME OF THE TEACHER: SR. RENCY GEORGE SUBJECT: BIOLOGY TOPIC: CHAPTER -1 CLASS: XI MOBILE NO:9340839715 CHAPTER-3 Plant Kingdom Objectives :- Observe plants closely to notice features and characteristics of growth and development. Observe and identify differences in plants and animals. Observe similarities among plants (seeds, roots, stems, leaves, flowers, fruit) Learning Strategies:- • Explain Different systems of Classification. • Differentiate between Artificial and Natural System of Classification. • Explain Algae and its significance. • Differentiate between various classes of Algae. • Explain various modes of reproduction in Algae. RESOURCES: i.Text books ii.Learning Materials iii.Lab manual iv.E-Resources,video ,L.C.D etc… CLICK HERE TO PLAY CONTENT RELATED VIDEO ON YOU TUBE. https://youtu.be/SWlVX1gDd98 https://youtu.be/P_MyyxIQzm4 https://youtu.be/KmbFGIiwP4k https://youtu.be/mepU8gStVpg https://youtu.be/fnE01M0YlTc https://youtu.be/xir7xvLi8XE Contents Introduction Plant kingdom includes algae, bryophytes, pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms. ... Depending on the type of pigment possessed and the type of stored food, algae are classified into three classes, namely Chlorophyceae, Phaeophyceae and Rhodophyceae. Eukaryotic, multicellular, chlorophyll containing and having cell wall, are grouped under the kingdom Plantae. It is popularly known as plant kingdom. • Phylogenetic system of classification based on evolutionary relationship is presently used for classifying plants. • Numerical Taxonomy use computer by assigning code for each character and analyzing the features. • Cytotaxonomy is based on cytological information like chromosome number, structure and behaviour. • Chemotaxonomy uses chemical constituents of plants to resolve the confusion. Algae: These include the simplest plants which possess undifferentiated or thallus like forms, reproductive organs single celled called gametangia. -

The Associations Between Pteridophytes and Arthropods

FERN GAZ. 12(1) 1979 29 THE ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN PTERIDOPHYTES AND ARTHROPODS URI GERSON The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Faculty of Agriculture, Rehovot, Israel. ABSTRACT Insects belonging to 12 orders, as well as mites, millipedes, woodlice and tardigrades have been collected from Pterldophyta. Primitive and modern, as well as general and specialist arthropods feed on pteridophytes. Insects and mites may cause slight to severe damage, all plant parts being susceptible. Several arthropods are pests of commercial Pteridophyta, their control being difficult due to the plants' sensitivity to pesticides. Efforts are currently underway to employ insects for the biological control of bracken and water ferns. Although Pteridophyta are believed to be relatively resistant to arthropods, the evidence is inconclusive; pteridophyte phytoecdysones do not appear to inhibit insect feeders. Other secondary compounds of preridophytes, like prunasine, may have a more important role in protecting bracken from herbivores. Several chemicals capable of adversely affecting insects have been extracted from Pteridophyta. The litter of pteridophytes provides a humid habitat for various parasitic arthropods, like the sheep tick. Ants often abound on pteridophytes (especially in the tropics) and may help in protecting these plants while nesting therein. These and other associations are discussed . lt is tenatively suggested that there might be a difference in the spectrum of arthropods attacking ancient as compared to modern Pteridophyta. The Osmundales, which, in contrast to other ancient pteridophytes, contain large amounts of ·phytoecdysones, are more similar to modern Pteridophyta in regard to their arthropod associates. The need for further comparative studies is advocated, with special emphasis on the tropics. -

Lesson 6: Plant Reproduction

LESSON 6: PLANT REPRODUCTION LEVEL ONE Like every living thing on earth, plants need to make more of themselves. Biological structures wear out over time and need to be replaced with new ones. We’ve already looked at how non-vascular plants reproduce (mosses and liverworts) so now it’s time to look at vascular plants. If you look back at the chart on page 17, you will see that vascular plants are divided into two main categories: plants that produce seeds and plants that don’t produce seeds. The vascular plants that do not make seeds are basically the ferns. There are a few other smaller categories such as “horse tails” and club mosses, but if you just remember the ferns, that’s fine. So let’s take a look at how ferns make more ferns. The leaves of ferns are called fronds, and brand new leaves that have not yet totally uncoiled are called fiddleheads because they look like the scroll-shaped end of a violin. Technically, the entire frond is a leaf. What looks like a stem is actually the fern’s equivalent of a petiole. (Botanists call it a stipe.) The stem of a fern plant runs under the ground and is called a rhizome. Ferns also have roots, like all other vascular plants. The roots grow out from the bottom of the rhizome. Ferns produce spores, just like mosses do. At certain times of the year, the backside of some fern fronds will be covered with little dots called sori. Sori is the plural form, meaning more than one of them. -

Pteridophyte Fungal Associations: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives

This is a repository copy of Pteridophyte fungal associations: Current knowledge and future perspectives. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/109975/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Pressel, S, Bidartondo, MI, Field, KJ orcid.org/0000-0002-5196-2360 et al. (2 more authors) (2016) Pteridophyte fungal associations: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 54 (6). pp. 666-678. ISSN 1674-4918 https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12227 © 2016 Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Pressel, S., Bidartondo, M. I., Field, K. J., Rimington, W. R. and Duckett, J. G. (2016), Pteridophyte fungal associations: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Jnl of Sytematics Evolution, 54: 666–678., which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12227. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. -

Curitiba, Southern Brazil

data Data Descriptor Herbarium of the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná (HUCP), Curitiba, Southern Brazil Rodrigo A. Kersten 1,*, João A. M. Salesbram 2 and Luiz A. Acra 3 1 Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná, School of Life Sciences, Curitiba 80.215-901, Brazil 2 REFLORA Project, Curitiba, Brazil; [email protected] 3 Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná, School of Life Sciences, Curitiba 80.215-901, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-41-3721-2392 Academic Editor: Martin M. Gossner Received: 22 November 2016; Accepted: 5 February 2017; Published: 10 February 2017 Abstract: The main objective of this paper is to present the herbarium of the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana’s and its collection. The history of the HUCP had its beginning in the middle of the 1970s with the foundation of the Biology Museum that gathered both botanical and zoological specimens. In April 1979 collections were separated and the HUCP was founded with preserved specimens of algae (green, red, and brown), fungi, and embryophytes. As of October 2016, the collection encompasses nearly 25,000 specimens from 4934 species, 1609 genera, and 297 families. Most of the specimens comes from the state of Paraná but there were also specimens from many Brazilian states and other countries, mainly from South America (Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Colombia) but also from other parts of the world (Cuba, USA, Spain, Germany, China, and Australia). Our collection includes 42 fungi, 258 gymnosperms, 299 bryophytes, 2809 pteridophytes, 3158 algae, 17,832 angiosperms, and only one type of Mimosa (Mimosa tucumensis Barneby ex Ribas, M. -

The Structure, Function, and Biosynthesis of Plant Cell Wall Pectic Polysaccharides

Carbohydrate Research 344 (2009) 1879–1900 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Carbohydrate Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/carres The structure, function, and biosynthesis of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides Kerry Hosmer Caffall a, Debra Mohnen a,b,* a University of Georgia, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, 315 Riverbend Road Athens, GA 30602, United States b DOE BioEnergy Science Center (BESC), 315 Riverbend Road Athens, GA 30602, United States article info abstract Article history: Plant cell walls consist of carbohydrate, protein, and aromatic compounds and are essential to the proper Received 18 November 2008 growth and development of plants. The carbohydrate components make up 90% of the primary wall, Received in revised form 4 May 2009 and are critical to wall function. There is a diversity of polysaccharides that make up the wall and that Accepted 6 May 2009 are classified as one of three types: cellulose, hemicellulose, or pectin. The pectins, which are most abun- Available online 2 June 2009 dant in the plant primary cell walls and the middle lamellae, are a class of molecules defined by the pres- ence of galacturonic acid. The pectic polysaccharides include the galacturonans (homogalacturonan, Keywords: substituted galacturonans, and RG-II) and rhamnogalacturonan-I. Galacturonans have a backbone that Cell wall polysaccharides consists of -1,4-linked galacturonic acid. The identification of glycosyltransferases involved in pectin Galacturonan a Glycosyltransferases synthesis is essential to the study of cell wall function in plant growth and development and for maxi- Homogalacturonan mizing the value and use of plant polysaccharides in industry and human health. -

NAPPC Pollinator Curriculum

NAPPC Pollinator Curriculum >>next Nature's Partners: Pollinators, Plants, and You | Copyright 2007 The Pollinator Partnership Please help us improve and expand this resource! Send us your comments, questions, and suggestions. Let us know how you are using the curriculum, what works well, and what challenges you're encountering. E-mail: [email protected] http://www.nappc.org/curriculum/9/25/2007 11:10:30 AM NAPPC Pollinator Curriculum Printer-Friendly View | Normal View Why Care About Pollinators? Many people think only of allergies when they hear Nature's Partners is an the word pollen. But pollination — the transfer of inquiry learning-based pollen grains to fertilize the seed-producing ovaries curriculum for young of flowers — is an essential part of a healthy people in the 3rd through ecosystem. Pollinators play a significant role in the Home the 6th grade. production of over 150 food crops in the United >>Learn more about the curriculum. States — among them apples, alfalfa, almonds, Why Care About blueberries, cranberries, kiwis, melons, pears, Pollinators? plums, and squash. Scientific Thinking Bees, both managed honey bees and native bees, Processes are the primary pollinators. However, more than 100,000 invertebrate species, including bees, moths, butterflies, beetles, and flies, serve as pollinators — Implementing the as well as 1,035 species of vertebrates, including Curriculum birds, mammals, and reptiles. In the United States, the annual benefit of managed honey bees to Assessment consumers is estimated at $14.6 billion. The services provided by native pollinators further contribute to Outline the productivity of crops as well as to the survival and reproduction of many native plants. -

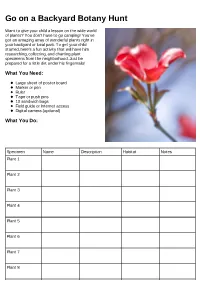

Go on a Backyard Botany Hunt

Go on a Backyard Botany Hunt Want to give your child a lesson on the wide world of plants? You don't have to go camping! You've got an amazing array of wonderful plants right in your backyard or local park. To get your child started, here's a fun activity that will have him researching, collecting, and charting plant specimens from the neighborhood. Just be prepared for a little dirt under his fingernails! What You Need: Large sheet of poster board Marker or pen Ruler Tape or push pins 10 sandwich bags Field guide or Internet access Digital camera (optional) What You Do: Specimen Name Description Habitat Notes Plant 1 Plant 2 Plant 3 Plant 4 Plant 5 Plant 6 Plant 7 Plant 8 Plant 9 Plant 10 1. Step 1 Before your child can embark on his botany hunt, he'll need to do a little research into the types of plants that are growing all around him. There are many ways to get the goods, but getting an illustrated field guide for your area from the library or bookstore is probably the best. Short of that, Internet research into the plants in your area should yield useful information and images. 2. Step 2 Get out in the garden! If you don't have access to a backyard, take a trip to a nearby park or nature area – anywhere plants can be found. Have your field guide with you to research and identify the plants that you see, and take photographs of the plants in their natural habitat.