Polish Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Government Data, the Case of Polish Public Sector

Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management A Publication of the International Institute for Applied Knowledge Management Volume 6, Issue 2, 2018 Special Issue on Knowledge Management: Research, Organization, and Applied Innovation Open government data, the case of Polish public sector Jędrzej Wieczorkowski, Warsaw School of Economics, Poland, [email protected] Ilona Pawełoszek, Częstochowa University of Technology, Poland, [email protected] Abstract This paper presents the idea of open government data along with the benefits and threats resulting from using open data. We describe the results of our research study on availability of the open data on the example of Poland with particular emphasis on Central Repository for Public Information (CRPI). The comparison of CRPI in Poland and other countries has been discussed. The review of accessible public information has been made with particular focus on data formats. Data formats are an important aspect of open data as they facilitate or impede the reuse of data. The insights from our participant observation in the projects of computerization of public administration are also presented. Although the Open Government Data (OGD) movement can provide a number of benefits, recent study has shown that in Poland it has not achieved its full potential yet. Keywords: Open data, open government data, linked data, central repository for public information. Introduction Idea of Open Government Data A concept of universal right of access to information is not new. It has been a subject of the public debate from the middle of the 18th century (Mendel, 2003). In the second part of 20th century the law of free access to information became a common standard in many countries. -

IFF Exco Meeting, by Skype, November 2Nd, 2015

Financial Report 31.10.2015 Balance sheet 31.10.2015 Appendix 2a COSTS Budget Outcome Compared Outcome ASSETS Cost Centre 30.11.2015 30.11.2014 /Ann.budget Current assets 01.01.2015 30.11.2015 10 Central activities 17800 12643,63 16398,62 5156 Cash 1500,00 1500,00 11 Office 656500 467783,71 476495,26 188716 Credit Suisse 559200-11 127160,84 159939,74 12 CB 38000 26614,81 40795,54 11385 13 ExCo 8500 2743,33 3501,27 5757 Receivables 14GA/AM 8500 0,00 0,00 8500 Claims 2010 100034,48 100034,48 15 External meetings 21000 13766,27 19599,38 7234 Claims 2011 44353,83 44353,83 16 IOC 50 Road Map 28200 25472,46 40512,92 2728 Claims 2012 60436,09 55336,09 17 Parafloorball 5000 4469,17 366,70 531 Claims 2013 72900,00 62200,00 18 Equality Function 7500 0,00 2162,43 7500 Claims 2014 274097,39 88250,00 19 Athletes Commission 9000 3872,79 2350,34 5127 Claims 2015 0,00 60220,40 20 WFC 100000 33711,85 38420,30 66288 Deferr expenses and accr income 0,00 0,00 21 U19 WFC 21000 9630,92 35147,99 11369 Receivables from rel.parties 26817,44 18486,67 22EFC 36500 23200,42 34362,77 13300 Total assets 707300,07 590321,21 23 Champions Cup 90000 44024,00 46920,00 45976 24World Games 0 0,00 0,00 0 LIABILITIES AND EQUITY 25 WUC 0 0,00 4614,57 0 26 Regional Games 0 19914,52 0,00 -19915 Current liabilities 29 Anti-Doping 27000 15492,65 17532,23 11507 Accr expenses and deferr income -204580,00 -122590,00 40RACC 22900 1000,00 7907,54 21900 Other current liabilities -15117,16 -9582,17 50 RC 42500 27915,83 18526,21 14584 Transfers to reserves -181847,03 -47164,74 60 Development -

SDS Annual Report 2010-2011

LEADING THE DEVELOPMENT OF SPORT IN SCOTLAND FOR PEOPLE OF ALL AGES AND ABILITIES WITH A PHYSICAL, SENSORY OR LEARNING DISABILITY Annual Report 2010 - 2011 www.scottishdisabilitysport.com Chairman’s Message A warm welcome to the 2011 AGM of Scottish Disability I hope you like our new website and its regular updates. Sport. More importantly I hope you use it on a regular basis as it becomes our main method of communication to all within Scottish Disability Sport would like to acknowledge with sincere thanks Once again the past year has flown in and as an disabled sport in Scotland. A big thank you to Richard who organisation we have achieved so much. I am delighted works tirelessly in the background refreshing and uploading the generous financial support received from the following Councils to with the way our staff have grown, the professionalism they all the information you pass on for the website. assist with hosting the AGM and producing this Annual Report: have shown in this past year, the additional programmes they have developed, assisting our new found athletes, the growth in training & development, the additional numbers in events, the summer camp, it’s all outstanding and there is so much more to do. I start by congratulating Gavin and our HQ staff as we undertook an Audit & Review of all our procedures through sportscotland and we were delighted to achieve ‘Reasonable Assurance’ on all our policies and procedures. The communication with our partners, in particular Governing Bodies of Sport and Local Authorities, continues to grow and our Regional Managers are producing a strong and healthy programme. -

Turniermagazin YGO 2016

Den schnellsten t der Welt Racket-Spor live erleben Die besten Badmintonspieler kämpfen um 120.000 US$ Preisgeld RWE-Sporthalle in Mülheim an der Ruhr Mehr Infos unter www.german-open-badminton.de Veranstalter: Vermarktungsgesellschaft Badminton Deutschland mbH (VBD) für den Deutschen Badminton-Verband e.V. (DBV) Ausrichter: 1. Badminton-Verein Mülheim an der Ruhr e.V. YONEX.DE IMPOSANTE KONTROLLE Überliste deine Gegner mit der überragenden Präzision und den perfekten Kontrollqualitäten eines ARCSABER Rackets. MARC ZWIEBLER ARCSABER 11 ARCSABER Schläger geben dir genau die Performance für Kontrolle, Präzision und Feeling, die du brauchst, um deinen Gegner bei jedem Schlag in Bedrängnis zu bringen. Nutze diesen Vorteil, damit du als Sieger vom Feld gehst. YONEX GMBH • 47877 Willich • Tel. 0 21 54 / 9 18 60 • Fax 0 21 54 / 91 86 99 • e-mail: [email protected] INHALT / IMPRESSUM | CONTENT / IMPRINT Inhalt | Content* Geleitwort/Grußworte | Foreword/Greetings Historie | History Ulrich Scholten, Oberbürgermeister Mülheim a. d. Ruhr 4 Austragungsorte seit 1955 16 Christina Kampmann, Sportministerin Land NRW 4 Venues since 1955 Poul-Erik Høyer, President Badminton World Federation 5 Die Finalspiele der YONEX German Open 2015 19 Finals of YONEX German Open 2015 Poul-Erik Høyer, Präsident Badminton-Weltverband 5 Letzter „Heimsieg“ im Jahr 1975 22 Karl-Heinz Kerst, Präsident Deutscher Badminton-Verband 6 Deutsche Titelträger seit 1955 22 Kusaki Hayashida, President YONEX Co., Ltd. 6 Marc Zwiebler schrieb Sportgeschichte 23 Kusaki Hayashida, Präsident YONEX Co., Ltd. 7 Erfolge der DBV-Asse seit März 2015 24 Frank Thiemann, 1. Vorsitzender 1. BV Mülheim 7 Ulrich Schaaf, Präsident Badminton-Landesverband NRW 8 Martina Ellerwald, Leiterin Mülheimer SportService 8 Hintergrund Deutsches Badminton-Zentrum Mülheim a. -

Person Greetid}

{PERSON_GREETID}, Gardos/Habesohn erreichen Semifinale bei World Tour in Polen. - Andreas Levenko nahm an World Cadet Challenge teil. - Österreichs Topteams im Champions Leagueeinsatz. WORLD TOUR POLEN Österreichs Nationalteamspieler waren bei der World Tour in Polen im Einsatz. Vizeeuropameister Robert Gardos und Daniel Habesohn schafften es bis ins Halbfinale des Doppelbewerbs. Auch Amelie Solja und Sofia Polcanova drangen bis ins Viertelfinale vor. lesen Sie mehr WORLD CADET CHALLENGE Von 26. Oktober bis 3. November fand in Otocec (SLO) die 2013 ITTF World Cadet Challenge statt. An diesem Turnier durften nur von der ITTF ausgewählte Spieler und Spielerinnen teilnehmen. Einer jener 32 Spieler war Andreas Levenko. lesen Sie mehr GJC UNGARN Österreichs Nachwuchsspieler waren beim stark besetzten Global Junior Circuit in Ungarn am Start. Karoline Mischek, David Klaus und Andreas Levenko konnten sich für den Hauptbewerb qualifizieren. lesen Sie mehr HERREN EUROPEAN CHAMPIONS LEAGUE SVS Niederösterreich und SPG Walter Wels mussten sich nach den Auftaktsiegen in ihren zweiten Spielen der European Champions League jeweils geschlagen geben. lesen Sie mehr DAMEN EUROPEAN CHAMPIONS LEAGUE Linz AG Froschberg eilt derzeit in der European Champions League von Sieg zu Sieg. SVS Ströck musst sich in Runde 3 TTC Berlin Eastside geschlagen geben, konnte aber in Runde 4 gegen das topgesetzte Team aus Fenerbahce gewinnen. lesen Sie mehr zu Runde 3 lesen Sie mehr zu Runde 4 SUPERLIGA FÜR KLUBTEAMS UTTC Stockerau konnte in der 4. Runde der Superliga für Klubteams einen weiteren wichtigen Sieg um den Aufstieg ins Champions Play-off feiern. Österreichs U21 Nationalteam musste sich wie schon auswärts gegen Dr. Casl, den Favoriten auf den Gruppensieg, geschlagen geben. -

Drawsheets Saturday Day 1

24th Polish Open and 20th Warsaw Cup Warsaw, Poland Tournament date: 16-9-2017 upto 17-9-2017 (NED) Seniors Male A -58 (Fly) (ITA) Janmaat, Giorgio B/645 B/568 Flecca, Antonio Taekwondo Amesfoort (NED) Active competitors: 36 G.S. Vigili del Fuoco Fiamme Rosse (NED) Competition date: 16-9-2017 (ITA) (ITA) B/645 B/568 411 415 B/733 Gasiorowski, Jan (14-8 PTF) (24-2 PTG) AZS OS Poznan (POL) (POL) (POL) R/733 R/997 Piaskowy, Kacper 401 (14-0 PTF) UKS Koryo (POL) R/858 Alhashim, Abdulhadi (NED) (ITA) Alsalam club (KSA) B/645 B/568 427 429 (10-4 PTF) (19-6 PTF) (GRE) (GBR) Bentoulis, Stergios B/460 B/332 Golding, Alex Kaisariani TKD CLUB (GRE) Great Britain National Team (GBR) (GBR) (BLR) R/329 R/1008 412 416 (7-25 PTF) (0-2 SDP) (GBR) (BLR) Levers, Joshua R/329 R/1008 Anushkevich, Yauheni Great Britain National Team (GBR) Belarusian National Team (BLR) (NED) 616 (MDA)(MDA) B/645 R/616 442 450 443 (27-12 PTF) (1-3 PTF) (RUS) (3-18 PTF) (BLR) Volkov, Danila B/848 B/43 Kokshyntsau, Illia SK Success (RUS) IMPORTANT: PLEASE NOTE! Belarusian National Team (BLR) (FRA) (BLR) B/233 Due to the no. of contestants, B/43 318.1 round 2 upto the final are 417 (13-15 PTF) (10-3 PTF) shown on schema page 3. (FRA) (POL) Alesio, Sebastien R/233 If your competitor reaches R/735 Kondrajczak, Dorian TAEKWONDO ROCAMORA (FRA) round 2, check only page 3 AZS OS Poznan (POL) for the rest of his/her fights. -

Informator Agh Ust En 2020 21.Pdf

13 | Foreword from AGH UST Rector 14 | AGH UST authorities in the years 2020–2024 15 | Mission Statement of AGH University of Science and Technology in Krakow 17 | From the pages of history 18 | Research University 11 | European University 12 | In Łukasiewicz Research Network 15 | Research – a source of innovation 18 | Transfer of technology and knowledge to the economy 20 | AGH UST acts for climate 22 | Education at the highest level 30 | Unlimited opportunities for development 32 | AGH UST in rankings 35 | AGH UST graduates on the labour market 38 | Unique campus 43 | University without barriers 44 | Artistic and cultural face 48 | Sports champions 51 | Bonds for the rest of life 52 | AGH UST campus map Spis treści photo by AGH UST Krakow Student Photo Agency photo by Maciek Bernaś, AGH UST Krakow Student Photo Agency 2 Foreword from AGH UST Rector Dear Readers, We are beginning the 2020–2024 term of office, and at the same time, the second century of our Alma Mater. Professor Jerzy Lis Rector of AGH UST in Krakow In front of the AGH UST academic community there are new plans, opportunities, and challenges. We will work on them together – as a community and the AGH UST family. The bar has been set very high both by the previous generations, and the university authorities in the previous terms of office. We have an important role to play in this generation relay. The strength of the AGH UST brand is a reason to be proud. The The aims that we have set ourselves university has a well-established position in Poland, and one that require hard work, but I am convinced is getting stronger abroad. -

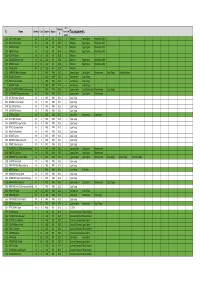

Polish Open Kaliber 2018 21-25 November 2018 POLAND, Bialystok

RESULTS BOOK BIAŁYSTOK POLAND 21 – 24.11.2018 Medal Standings After 10 of 10 Events Individual Team Subtotal Rk TEAM - NATION Total G S B G S B G S B 1 POLAND POL 2 2 1 2 1 2 4 2 8 2 UKRAINE UKR 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 4 3 GERMANY GER 1 1 2 0 0 2 4 BELARUS BLR 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 5 ISRAEL ISR 1 1 1 1 0 2 6 UKRAINE2 UKR 1 1 1 0 1 2 7 BLR - DINAMO Minsk BLR 1 1 0 0 1 8 FRANCE FRA 2 1 0 2 1 3 9 HUN - OLYMPIA SE Komaro HUN 1 0 1 0 1 9 LITHUANIA LTU 1 0 1 0 1 10 BLR - BOKCOR Brest BLR 1 0 0 1 1 10 LATVIA LAT 1 0 0 1 1 10 LTU - SRC Alytus LTU 1 0 0 1 1 10 POL - SOKÓŁ Zduńska Wola POL 1 0 0 1 1 Polish Open Kaliber 2018 21-25 November 2018 POLAND, Bialystok 10m Air Rifle Men Qualification APROVED RESULTS 24.11.2018 RP: 629,1 - BARTNIK Tomasz - LEGIA Warszawa - ZM Białystok 27.11.2015 Mc Name year b Team Series total x 1 SIDI Peter 1978 HUN - OLYMPIA SE Komaro 103,7 105,9 106,5 105,3 105,0 105,1 631,5 2 RICHTER Sergey 1989 ISRAEL 104,4 104,0 104,6 105,6 103,6 106,0 628,2 3 GIRULIS Karolis 1986 LTU - SRC Alytus 104,4 104,0 103,9 104,3 104,4 106,4 627,4 4 BARTNIK Tomasz 1990 POLAND 103,1 104,2 103,3 105,4 104,4 104,9 625,3 5 BAUDOUIN Brian 1994 FRANCE 104,7 104,9 101,9 105,2 105,1 103,2 625,0 6 BUBNOVICH Vitali 1974 BELARUS 104,3 104,4 103,8 105,0 104,4 103,0 624,9 7 SAMPSON Dane 1986 AUSTRALIA 103,5 103,7 102,8 105,9 105,1 103,8 624,8 8 KULISH Serhii 1993 UKRAINE2 103,0 102,4 106,1 105,1 104,7 103,1 624,4 9 TSARKOV Oleg 1988 UKRAINE 104,2 104,2 105,1 104,7 102,9 103,2 624,3 10 KURKI Juho 1991 FINLAND 103,0 103,7 103,7 104,3 104,4 104,8 623,9 11 KHABAROV Oleksii -

Tokyo 2020 TCS After Polish Open 2020 Without Criteria A.Xlsx

Criteria Nr of ID Name Gender Class Country Region Tourn.Com Tournaments B pleted 6210 ZAIDI Khier Eddine M 4 ALG AFR B 3/1 3 AlWatani Egypt Open Panafrican 2019 6211 SOUALEM Lakhdar M 5 ALG AFR B 3/1 3 AlWatani Egypt Open Panafrican 2019 5317 MERAZKA Farid M 7 ALG AFR B 3/1 3 AlWatani Egypt Open Panafrican 2019 6209 ABBASI Achour M 7 ALG AFR B 3/1 3 AlWatani Egypt Open Panafrican 2019 5316 BELAKRI Bachir M 8 ALG AFR B 1/1 1 AlWatani 2416 BOUMEDOUHA Karim M 10 ALG AFR B 3/1 3 AlWatani Egypt Open Panafrican 2019 5903 ZERIGUI Madani M 10 ALG AFR B 3/1 3 AlWatani Egypt Open Panafrican 2019 6212 TOUMI Billel M 10 ALG AFR B 1/1 1 AlWatani 5133 GARRONE Maria Costanza F 2 ARG AME B 5/2 5 Lignano Open Lasko Open Panamerican Copa Tango Costa Rica Open 5924 BLANCO Veronica F 3 ARG AME B 2/2 2 Panamerican Copa Tango 5391 KUELL Nayla Soledad F 5 ARG AME B 2/2 2 Panamerican Copa Tango 19 MUNOZ Giselle F 7 ARG AME B 2/2 2 Panamerican Copa Tango 2822 BUSTAMANTE SIERRA Guillermo Jose M 1 ARG AME B 4/2 4 Lignano Open Costa Brava Open Panamerican Copa Tango 3544 EBERHARDT Fernando Emanuel M 1 ARG AME B 3/2 3 Lignano Open Lasko Open Panamerican 5745 RIVERO Hector Eduardo M 1 ARG AME B 1/2 1 Copa Tango 5554 MUNOZ Luis Fernando M 2 ARG AME B 1/2 1 Copa Tango 5746 CELLI Silvio Martin M 2 ARG AME B 1/2 1 Copa Tango 5747 LANGARD Federico M 2 ARG AME B 1/2 1 Copa Tango 31 COPOLA Gabriel M 3 ARG AME B 3/2 3 Lasko Open Panamerican Copa Tango 2334 LOUSTRIC Rolando M 3 ARG AME B 1/2 1 Copa Tango 3364 GARAVENTO Lujan Nicolas M 3 ARG AME B 1/2 1 Copa Tango 3546 NETTO -

Modul-2-Buku-Olah-Raga-Paket-C.Pdf

MODUL 2 MODUL 2 Raih Kemenangan i Kata Pengatar Daftar Isi endidikan kesetaraan sebagai pendidikan alternatif memberikan layanan kepada mayarakat yang Judul Modul ............................................................................................ i karena kondisi geografis, sosial budaya, ekonomi dan psikologis tidak berkesempatan mengikuti Kata Pengantar ........................................................................................ ii Ppendidikan dasar dan menengah di jalur pendidikan formal. Kurikulum pendidikan kesetaraan Daftar Isi .................................................................................................. iii dikembangkan mengacu pada kurikulum 2013 pendidikan dasar dan menengah hasil revisi berdasarkan Petunjuk Penggunaan Modul .................................................................. iv Tujuan yang Diharapkan Setelah Mempelajari Modul ............................. iv peraturan Mendikbud No.24 tahun 2016. Proses adaptasi kurikulum 2013 ke dalam kurikulum pendidikan Pengantar Modul ..................................................................................... v kesetaraan adalah melalui proses kontekstualisasi dan fungsionalisasi dari masing-masing kompetensi dasar, sehingga peserta didik memahami makna dari setiap kompetensi yang dipelajari. Unit 1:Disiplin Dalam Berlatih .............................................................. 1 A. Bagaimana berlatih bulutangkis? .......................................... 2 Pembelajaran pendidikan kesetaraan menggunakan prinsip flexible -

Annual Report 2008/09 and Statement of Accounts

ANNUAL REPORT 2008/09 AND STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2009 ETTA Mission Statement OUR VISI O N To provide an environment that promotes and supports active, lifelong participation in Table Tennis at all levels whilst striving to identify and develop Commonwealth, European, World and Olympic/Paralympic champions. OUR MISSI O N Working in partnership to create opportunities for all to enjoy the sport of Table Tennis, to stay in the sport and achieve their full potential. OUR OBJECTI V ES • Grow - increase participation in Table Tennis with a focus on priority groups in the school, club, league and community sectors. • Sustain - to provide a positive experience and retain people in Table Tennis through an effective network of accredited clubs, facilities, coaches, officials, volunteers, leagues and other competitive opportunities. • Excel - to achieve medal success at European, Commonwealth, World and Olympic/Paralympic level. • Corporate Governance and Modernisation - to ensure we operate and deploy our resources with maximum efficiency, effectiveness and probity. OUR RO LE • To be the strategic lead for the development of Table Tennis in England. • To improve the quality of experience in Table Tennis of our members, customers and partners. • To inform, influence and persuade public opinion and key decision makers in sport of the benefits to society from participation and investment in Table Tennis. OUR VALUES • Honesty and integrity – promoting and encouraging fair play. • Leadership – providing effective, focused and inspirational leadership. • Community spirit – providing an inclusive community for elite, developing, social players and families. • Equal opportunity – providing for diverse needs of age, culture and disability. -

(BWF) Badminton

QUALIFICATION SYSTEM – GAMES OF THE XXXII OLYMPIAD – TOKYO 2020 BADMINTON WORLD FEDERATION (BWF) Badminton A. EVENTS (5) Men’s Events (2) Women’s Events (2) Mixed Event (1) Singles Singles Mixed Doubles Doubles Doubles B. ATHLETES QUOTA 1. Total Quota for Badminton: Tripartite Commission Qualification Host Country Total Invitation Places Places Places Men 82 1 3 86 Women 82 1 3 86 Total 164 2 6 172 2. Maximum Number of Athletes per NOC (across all 5 events): Quota per NOC Men 8 Women 8 Total 16 NOC event specific quota: Maximum Quota Places per Race to Tokyo Ranking Lists as of 15 June event 2021 If all athletes are ranked 1 - 16 2 Quota Places (2 athletes) Singles If one (1) athlete is included in the BWF Ranking 1 Quota Place (1 athlete) If all pairs are ranked 1 - 8 2 Quota Places (4 athletes) Doubles If one (1) is included in the BWF Ranking 1 Quota Place (2 athletes) Original Version: ENGLISH 25 February 2021 Page 1/8 QUALIFICATION SYSTEM – GAMES OF THE XXXII OLYMPIAD – TOKYO 2020 3. Number of athletes per event Initial Number of Athletes per Event* Men’s Singles 38 Women’s Singles 38 Men’s Doubles 32 (16 pairs) Women’s Doubles 32 (16 pairs) Mixed Doubles 32 (16 pairs) Total 172 *Before reallocation of quota places to Singles for athletes participating in both Singles and Doubles events 4. Type of Allocation of Quota Places: The quota place is allocated to the athlete(s) by name. If an NOC has more athletes/pairs qualified in any event than its entitled number of Quota Places, according to the Race to Tokyo Ranking Lists as 15 June 2021, the NOC can decide to decline a Quota Place allocated to the highest ranked athlete/pair and choose a lower ranked eligible athlete/pair during the different phases of reallocation of Quota Places, as detailed in paragraph F.