Rose Macaulay: Satirist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

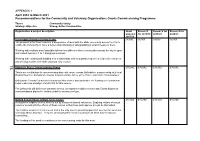

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme Theme Community Safety Strategic Objective Strong, Active Communities Organisation & project description Grant Recom’d Recom’d for Recom’d for awarded for 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2017/18 Donnington Doorstep Family Centre £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 The proposal is for them to deliver a programme of work with the BME community across the City to enable the community to have a better understanding of safeguarding at what it means to them. Working with mothers and if possible fathers from different ethnic communities across the city in open and closed sessions, 1 to 1 and group sessions. Working with existing and building new relationships with local partner agencies to identify resources and develop toolkits on behalf of Oxford City Council. 75 Domestic Abuse Commissioning Group £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 This is our contribution to commissioning domestic abuse across Oxfordshire in partnership with local District Councils, Oxfordshire County Council and the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner. Oxfordshire County Council will commission this service and administer the funding our contribution helps makes up a budget of £600,000 for this service. For Oxford this will deliver an outreach service, a telephone helpline service and 5 local dispersed accommodation places for victims unable to access a refuge. Oxford Sexual Abuse & Rape Crisis Centre £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 A telephone helpline service which is run by a team of trained volunteers. Enabling victims of sexual violence to deal with the effects of these crimes in their lives and improve access to information. -

LGBTQ+ Campaign

LGBTQ+ Campaign LGBTQ+ Campaign 1 CONTENTS INTRO 4 What is this and who is it for? 4 ADMINISTRATIVE QUESTIONS 5 How do I change my gender marker on my student record? 5 How do I change my name on my student record? 6 How do I change my title? 8 How do I change my name on my University Card(BodCard)? 8 Can I change the photo on my BodCard? 9 How do I change my name on my email? 10 How do I get my name changed on my pigeon hole (‘pidge’)? 11 What name will appear on my Degree Certificate? 11 How do I change my pronouns? 12 What records do college/the University keep of my name and gender marker? 12 What do I need to do to (re-)register to vote once I’ve changed my name? 13 HEALTH CARE QUESTIONS 14 How/where can I access trans-friendly doctors and healthcare? 14 Am I allowed to take time of for transitional purposes? 15 2 TRANS STUDENT OXFORD SURVIVAL GUIDE WELFARE QUESTIONS 16 How should I inform my academic tutors about my change of gender and/or name? 16 Which members of staf are a good point of contact? 17 Who can I talk to for welfare? Is there any student support in college? 19 FINANCE QUESTIONS 20 Can I apply for a transition fund through college? 20 What should I do if I’m facing financial dificulties because of my gender identity? 21 What should I do if my course involves travel abroad? 22 How do I change my name and gender with Student Finance England? 22 Do I need to buy a new sub fusc? 23 SOCIAL / OTHER QUESTIONS 23 Which hairdressers in Oxford are trans-friendly? 23 Where can I find gender-neutral toilets in town? 24 Are there any trans-inclusive sports groups? 25 Where can I find more support? 26 MY RIGHTS 28 What are my rights? 28 How do I report harassment? 29 Where can I find more information? 30 LGBTQ+ Campaign 3 INTRO What is this and who is it for? This is a guide put together by the Oxford SU LGBTQ+ Campaign’s Trans Rep of 2017/18 to provide practical information for trans students that should help them with various aspects of their transition in college and university. -

Attachment Data/File/404748/Align Change of Name G Uidance - V1 0.Pdf

Application: University of Oxford 2020 Workplace Equality Index Summary ID: A-1607368893 Last submitted: 9 Sep 2019 10:44 AM (UTC) Section 1: Employee Policy Completed - 16 Mar 2020 Workplace Equality Index submission Policies and Benefits: Part 1 Section 1: Policies and Benefits This section comprises of 7 questions and examines the policies and benefits the organisation has in place to support LGBT staff. The questions scrutinise policy audit process, policy content and communication. This section is worth 7.5% of your total score. Below each question you can see guidance on content and evidence. At any point, you may save and exit the form using the buttons at the bottom of the page. 1 / 135 1.1 Does the organisation have an audit process to ensure relevant policies (for example, HR policies) are explicitly inclusive of same-sex couples and use gender neutral language? GUIDANCE: The audit process should be systematic in its implementation across all relevant policies. Relevant policies include HR policies, for example leave policies. Yes Please describe the audit process: State when the process last happened: A proportionate review date is agreed for policies when they are created e.g. the Harassment Policy and Procedure has a three year review date (revised in 2014 and 2017). Describe the audit process: Governance at Oxford is democratic and its 70+ policies have been through a rigorous and widespread consultation and audit process in their creation and subsequent reviews. The process can take anything from six months to three years. With this in mind audits are not run concurrently. -

The Single Equality Scheme Report of Public Engagement May 2009

APPENDIX 2 The Single Equality Scheme Report of Public Engagement May 2009 Author(s) Sara Price, Communications & Engagement Project Coordinator Status Final version Date 31st May 2009 Contents 1. ABOUT OXFORDSHIRE PCT............................................................................................- 3 - 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................- 4 - 2.1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................- 4 - 2.2 PURPOSE OF THE PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT REPORT.......................................................................- 4 - 2.3 PURPOSE OF ENGAGEMENT.................................................................................................- 4 - 2.4 PROCESS & METHODOLOGY................................................................................................- 5 - 2.5 KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................................- 5 - 2.6 CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................- 6 - 3. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................- 7 - 3.1 THE WIDER CONTEXT.........................................................................................................- 7 - Defining equality and diversity ...........................................................................................- -

Final Version

The LGBT Guide to Study Abroad Distributed by Programs Abroad Chile 3 China 3 Ghana 4 Hong Kong 4 Japan 5 London; Oxford 5 Madrid 6 Paris 6 Tübingen 7 Citations 7 Dear Student, The Pew Research Center conducted a world-wide survey between March and May of 2013 on the subject of homo- sexuality. They asked 37,653 participants in 39 countries, “Should society accept homosexuality?” The results, summariZed in this graphic, are revealing. There is a huge variance by region; some countries are extremely divided on the issue. Others have been, and continue to be, widely accepting of homosexuality. This information is relevant not only to residents of these countries, but to travelers and students who will be studying abroad. Students going abroad should be prepared for noted differences in attitudes toward individuals. Before depar- ture, it can be helpful for LGBT students to research cur- rent events pertaining to LGBT rights, general tolerance of LGBT persons, legal protection of LGBT individuals, LGBT organizations and support systems, and norms in the host culture’s dating scene. We hope that the following summaries will provide a starting point for the LGBT student’s exploration of their destination’s culture. If students are in homestay situations, they should consider the implications of coming out to their host family. Students may choose to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid tension in the student-host family relationship. Other times, students have used their time away from their home culture as an opportunity to come out. Some students have even described coming out overseas as a liberating experience, akin to a “second” coming out. -

Gregory Pardlo's

Featuring 307 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVI, NO. 8 | 15 APRIL 2018 REVIEWS Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Gregory Pardlo’s nonfiction debut, Air Traffic: A Memoir of Ambition and Manhood in America, is masterfully personal, with passages that come at you with the urgent force of his powerful convictions. p. 58 from the editor’s desk: Chairman Four Excellent New Books HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY CLAIBORNE SMITH MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy Michael Thad Carter courtesy Photo Editor-in-Chief Our Little Secret by Roz Nay (Apr. 24): “First love goes bad in Nay’s mesmer- CLAIBORNE SMITH izing debut. Cove, Vermont, is a tidy town, and 15-year-old Angela Petitjean felt [email protected] Vice President of Marketing very out of place when she moved there 11 years ago with her well-meaning but SARAH KALINA [email protected] cloying parents. Then she met Hamish “HP” Parker. HP looked like a young Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU Harrison Ford and lit up every room he walked into, whereas Angela was quiet [email protected] Fiction Editor and thoughtful. They became the best of friends and stayed that way until a LAURIE MUCHNICK graduation trip to the lake, when they realized they were in love….Nay expertly [email protected] Children’s Editor spins an insidious, clever web, perfectly capturing the soaring heights and crush- VICKY SMITH [email protected] ing lows of first love and how the loss of that love can make even the sanest Young Adult Editor Claiborne Smith LAURA SIMEON people a little crazy. -

Rose Macaulay: Satirist Suzanne F

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 1-1-1964 Rose Macaulay: Satirist Suzanne F. Carey Butler University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Carey, Suzanne F., "Rose Macaulay: Satirist" (1964). Graduate Thesis Collection. Paper 12. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Name of candidate: Oral examination: Date /9 6 Committee: , Chairman Thesis title: czy Thesis approved in final form: Date Major Professor ROSE MACAULAY: SATIRIST by SUZANNE FULTON CAREY A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Division of Graduate Instruction Butler University 1964 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Chapter I. The Shaping Factors 3 Early Environment 3 Temperament 7 Literary Influences 15 Chapter II. Satiric Techniques 22 Reverse Utopia 22 Parody 23 Invective 25 Mimicked Conversation 26 Verbal Irony 34 Dramatic Irony 41 Symbolism • . • • 0 • o OOOOOOO o • • • 43 Satiric Characterization 46 Chapter III. Multiple Stances OOOOOO 0 •••. OOOOOO 58 Chapter IV. The Summing Up 89 Bibliography of Rose Macaulay t s Works 97 A Selected Bibliography 99 Introduction Dame Rose Macaulay possessed two qualities, a comic spirit and an intellectual pessimism, which made her one of England's finest modern satirists. Her satire has limitations. First, because of rapid and rather prolific productivity, some of the satire is repetitious. -

LGBTQ+ HISTORY MONTH 2019 History: Peace, Reconciliation, Activism

LGBTQ+ HISTORY MONTH 2019 History: peace, reconciliation, activism Events throughout February and March 2019 celebrating lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender history, organised by Oxford Brookes University, Brookes Union, University of Oxford and local community groups. Introduction Professor Anne-Marie Kilday Pro Vice-Chancellor (Student and Staff Experience) Oxford Brookes University Welcome to LGBTQ+ History experiences and activism for Month 2019. This represents LGBTQ+ equality and inclusion in Oxford Brookes fourth year of the wider world. collaboration to celebrate and highlight achievements, voices Oxford Brookes University from the LGBTQ+ community celebrates and values the diversity and perspectives on LGBTQ+ of our students and staff and aims equality and inclusion. The to create an organisational culture diverse programme collates a which is fully inclusive of diverse range of events organised by sexual orientations, gender identity staff and students of Oxford and gender expression. Brookes together with other local organisations and wider In focusing on visibility, voice, community activity. promoting awareness and sharing learning and experiences, LGBTQ+ I am delighted to invite everyone History Month gives us all an to connect and reflect on how our opportunity to further our personal identities and communities relate and organisational journeys for to our local and global context, equality and “acceptance without and broaden understanding of exception”. For more information about equality, diversity and inclusion at -

Testament of Youth

WOMEN’S WRITING OF WORLD WAR I DISCOURSES OF FEMINISM AND PACIFISM IN ROSE MACAULAY’S NON-COMBATANTS AND OTHERS AND VERA BRITTAIN’S TESTAMENT OF YOUTH Joyce Van Damme Student number: 01302613 Supervisor: Dr. Birgit Van Puymbroeck Master thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” Academic year: 2016 – 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Birgit Van Puymbroeck, for her guidance, feedback, and support. Thank you for always being ready to answer any questions I had and for your engagement throughout the process. I would also like to thank my friends and family for their love and support. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historical Context of the First World War 9 3. Discourses of Feminism and Pacifism in Rose Macaulay’s Non-Combatants and Others 15 3.1 Biographical Introduction to Macaulay and her Feminism and Pacifism 15 3.2 Discourses of Feminism 19 3.3 Discourses of Pacifism 25 3.4 How Feminism and Pacifism Are Connected 34 4. Discourses of Feminism and Pacifism in Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth 38 4.1 Biographical Introduction to Brittain and her Feminism and Pacifism 38 4.2 Discourses of Feminism 42 4.3 Discourses of Pacifism 48 4.4 How Feminism and Pacifism Are Connected 56 5. Comparison of Discourses of Feminism and Pacifism in Non-Combatants and Others and Testament of Youth 58 5.1 Difference in Discourse 58 5.2 Comparison of Development of Feminist and Pacifist Discourses 63 6. -

LGBTQ Leaflet 2014

LGBTQ AT ORIEL ORIEL’S OPINIONS A HANDY GUIDE TO Eleanor Sharman “I'm firmly under the ‘Q’ banner, and would happily say that the JCR has an LGBTQ incredibly active, supportive attitude AT OXFORD UNIVERSITY towards those of non-normative identities. Change happens slowly in Oxford, but Oriel is doing us proud in standing up for individuality and freedom.” Jonathan Lester “As someone who identifies as gay, I have found living in Oxford a much more comfortable experience than the area in which I grew up. I also find Oriel a welcoming and Oriel’s recent history has been a good one for warm place, despite its traditional LGBTQ rights. reputation.” Last year, Oriel College flew the LGBTQ rainbow flag Jonathan Sanders several times, and many students flew the flag from “For those who identify as LGBTQ, their own windows to celebrate. Last year’s LGBTQ starting out at uni can bring with it representative Joey Dunlop fought hard for the concerns about how their orientation student press to drop its negative stereotyping of might shape their social life, but Oriel. Oxford offers so many academic and social opportunities that sexual During the year, Oriel held a variety of events to orientation doesn't have to play a promote equality, including a ‘queer bop’ (a night in large part in deciding how your time the bar dedicated to appreciating LGBTQ culture), a here will unfold.” talk from transgender author and artist S. Bear Bergman, and a discussion event around the concept Information, advice and of ‘queerness’. Rowan Milligan support for Oriel’s lesbian, “What makes Oxford’s LGBTQ gay, bisexual, trans and queer Oriel JCR subscribes to NoHeterox**, Oxford’s queer scene great is its diversity. -

Introduction

Introduction Book or Report Section Accepted Version Macdonald, K. (2017) Introduction. In: Macdonald, K. (ed.) Rose Macaulay, Gender, and Modernity. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 1-34. ISBN 9781138206175 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/69002/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Routledge All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online [title]Chapter 1: Introduction [author]Kate Macdonald This is the first collection of essays to be published on the prolific, intelligent writing of the British novelist and woman of letters, Rose Macaulay (1881-1958). The essays work on a number of levels. Many draw on Macaulay's writing to establish connections between two movements that are usually separated by literary-critical demarcations: modernism and the middlebrow. Macaulay is placed in relation to writers from these movements to illustrate how her work mediates between these two modes of writing. The essays focus on gender and genre using key texts to explore how Macaulay’s negotiation of modernist modes and middlebrow concerns produced writing that navigated the perceived gulf between 'feminine', middlebrow writing inflected by popular culture, and more 'masculine', elitist forms of modernism. In 1946 the historian C V Wedgwood described Macaulay’s writing voice as ‘unmistakeable along writers of our time. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details A Moral Business: British Quaker work with Refugees from Fascism, 1933-39 Rose Holmes Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex December 2013 i I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: ii University of Sussex Rose Holmes PhD Thesis A Moral Business: British Quaker work with Refugees from Fascism, 1933-39 Summary This thesis details the previously under-acknowledged work of British Quakers with refugees from fascism in the period leading up to the Second World War. This work can be characterised as distinctly Quaker in origin, complex in organisation and grassroots in implementation. The first chapter establishes how interwar British Quakers were able to mobilise existing networks and values of humanitarian intervention to respond rapidly to the European humanitarian crisis presented by fascism. The Spanish Civil War saw the lines between legal social work and illegal resistance become blurred, forcing British Quaker workers to question their own and their country’s official neutrality in the face of fascism.