David Weekes Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

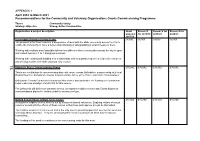

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme Theme Community Safety Strategic Objective Strong, Active Communities Organisation & project description Grant Recom’d Recom’d for Recom’d for awarded for 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2017/18 Donnington Doorstep Family Centre £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 The proposal is for them to deliver a programme of work with the BME community across the City to enable the community to have a better understanding of safeguarding at what it means to them. Working with mothers and if possible fathers from different ethnic communities across the city in open and closed sessions, 1 to 1 and group sessions. Working with existing and building new relationships with local partner agencies to identify resources and develop toolkits on behalf of Oxford City Council. 75 Domestic Abuse Commissioning Group £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 This is our contribution to commissioning domestic abuse across Oxfordshire in partnership with local District Councils, Oxfordshire County Council and the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner. Oxfordshire County Council will commission this service and administer the funding our contribution helps makes up a budget of £600,000 for this service. For Oxford this will deliver an outreach service, a telephone helpline service and 5 local dispersed accommodation places for victims unable to access a refuge. Oxford Sexual Abuse & Rape Crisis Centre £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 A telephone helpline service which is run by a team of trained volunteers. Enabling victims of sexual violence to deal with the effects of these crimes in their lives and improve access to information. -

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Guide to John Buchan's Writing

Guide to John Buchan’s writing – issue no. 5 Please contact me for full details of any book which may be of interest. Section A A24 The Moon Endureth (1912) A collection of 10 poems and 10 short stories with each poem being followed by a story. Both the poems and the stories are wide-ranging in their subject matter and make an interesting mix. All but two of the poems were published here for the first time, the others having appeared in the Book of the Horace Club (see the entry under C3 in JB guide 01). The stories had all been published previously, mostly in magazines although the closing story had also appeared in Grey Weather (see A9 in JB guide 02). The US edition omits 3 of the stories and 2 of the poems but includes an additional story, Fountainblue, which had previously appeared in The Watcher by the Threshold (see A13 in JB guide 03). This title was published in the Nelson Uniform edition and Hodder’s Yellow Jacket series. It was not included in Nelson’s 1/6 or 2/- novels. Copies available (17.08.19) First edition – 3 copies £70 to £100. US first edition – 1 copy. Second impression (as first) – 1 copy £25. Nelson Uniform green leather version – 2 copies £17.50 to £19. Large format Yellow Jacket edition – 3 copies £40 to £60. Hodder & Stoughton reprints – 2 copies £7 to £8. A25 What the Home Rule Bill Means (1912) Buchan had strong views on the question of Irish Home Rule and as Prospective Union Candidate for Peebles and Selkirk he took the opportunity to make a speech on this issue in Innerleithen on 18 December 1912. -

The Thirty-Nine Steps 4 5 by John Buchan 6

Penguin Readers Factsheets level E Teacher’s notes 1 2 3 The Thirty-nine Steps 4 5 by John Buchan 6 SUMMARY PRE-INTERMEDIATE ondon, May 1914. Europe is close to war. Spies are he was out of action, he began to write his first ‘shocker’, L everywhere. Richard Hannay has just arrived in as he called it: a story combining personal and political London from Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in Africa to dramas. This book was The Thirty-nine Steps, published start a new life. One evening a man appears at his door in 1915. The novel marked a turning point in Buchan’s and asks for help. His name is Scudder and he is a literary career and introduced his famous adventuring THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS freelance spy, working alone. He has uncovered a German hero, Richard Hannay. The story was a great success with plot to murder the Greek Prime Minister in London and to the men in the First World War trenches. One soldier wrote steal the British plans for the outbreak of war. He is on the to Buchan, ‘The story is greatly appreciated in the midst trail of a ring of German spies, called the Black Stone. of mud and rain and shells, and all that could make trench Hannay takes Scudder into his house and learns his life depressing.’ secrets. German spies are in the street outside, watching Buchan continued to work for the intelligence services the house. during and after the war and Richard Hannay continued A few days later, Hannay returns to his flat after dinner his adventures in Greenmantle and other stories. -

In Memoriam COMPILED by GEOFFREY TEMPLEMAN

In Memoriam COMPILED BY GEOFFREY TEMPLEMAN The Alpine Club Obituary Year of Election Charles Buchanan Moncur Warren 1931 Hon. 1980 Janet Buchanan Carleton (Janet Adam Smith) LAC 1946 Hon. 1994 Geoffrey John Streetly ACG 1952 Stephen Paul Miller Asp. 1999 Frederic Sinclair Jackson 1957 Christine Bicknell LAC 1949 Sir George Sidney Bishop 1982 John Flavell Coa1es 1976 Robert Scott Russell 1935 A1istair Morgan 1976 Arun Pakmakar Samant 1987 In addition to the above eleven members who died in 1999, mention should be made of four further names. Jose Burman, a South African member, died in 1995 but was not included at the time. Ginette Harrison was the first woman to climb Kangchenjunga, in 1998. Whilst not yet a member, she had started the application process for membership. She died on Dhaulagiri last year. Yossi Brain, who sent us valuable reports from South America for the Area Notes, died in an avalanche on 25 September 1999 while mountain eering with friends in Northern Bolivia. Yossi touched the lives of a lot of people, through his lively, bright, and often irreverent sense of humourwhich permeated his guiding, his books, his articles and above all his spirit. He achieved a lot in the time he had, making two different and sucessful careers, and providing inspiration to many. Ulf Carlsson was Chairman of the Mountain Club of Kenya between 1993 and 1996. He wrote an article about the Swedish mountains for the 1997 Alpine Journal and was well known to some of our members. He died in the Pamir in 1999. Geoffrey Templeman 277 278 THE ALPINE JOURNAL 2000 Charles Warren, 1906-1999 Our Honorary Member Charles Warren, who died at Felsted a few days short of his 93rd birthday, was the oldest surviving member of the pre-war Everest expeditions. -

LGBTQ+ Campaign

LGBTQ+ Campaign LGBTQ+ Campaign 1 CONTENTS INTRO 4 What is this and who is it for? 4 ADMINISTRATIVE QUESTIONS 5 How do I change my gender marker on my student record? 5 How do I change my name on my student record? 6 How do I change my title? 8 How do I change my name on my University Card(BodCard)? 8 Can I change the photo on my BodCard? 9 How do I change my name on my email? 10 How do I get my name changed on my pigeon hole (‘pidge’)? 11 What name will appear on my Degree Certificate? 11 How do I change my pronouns? 12 What records do college/the University keep of my name and gender marker? 12 What do I need to do to (re-)register to vote once I’ve changed my name? 13 HEALTH CARE QUESTIONS 14 How/where can I access trans-friendly doctors and healthcare? 14 Am I allowed to take time of for transitional purposes? 15 2 TRANS STUDENT OXFORD SURVIVAL GUIDE WELFARE QUESTIONS 16 How should I inform my academic tutors about my change of gender and/or name? 16 Which members of staf are a good point of contact? 17 Who can I talk to for welfare? Is there any student support in college? 19 FINANCE QUESTIONS 20 Can I apply for a transition fund through college? 20 What should I do if I’m facing financial dificulties because of my gender identity? 21 What should I do if my course involves travel abroad? 22 How do I change my name and gender with Student Finance England? 22 Do I need to buy a new sub fusc? 23 SOCIAL / OTHER QUESTIONS 23 Which hairdressers in Oxford are trans-friendly? 23 Where can I find gender-neutral toilets in town? 24 Are there any trans-inclusive sports groups? 25 Where can I find more support? 26 MY RIGHTS 28 What are my rights? 28 How do I report harassment? 29 Where can I find more information? 30 LGBTQ+ Campaign 3 INTRO What is this and who is it for? This is a guide put together by the Oxford SU LGBTQ+ Campaign’s Trans Rep of 2017/18 to provide practical information for trans students that should help them with various aspects of their transition in college and university. -

December 2008 Membership T a N D R E O F L O S a I N T a N E S G E L Dues T H E S

the histle w ’ s S o c i e t y December 2008 Membership t A n d r e o f L o s a i n t A n e S g e l Dues T h e s a message from John Benton, M.D., President Hogmanay here's little of the will celebrate the bard’s 250th A guid New Year to ane an membership dues are Tyear 2008 left. It's anniversary (invitations will be a and mony may ye see! payable by January 31, been a busy one, and mailed soon and I encourage you Dues notices were 2009. there's much yet to do to sign up early to avoid mailed to all members ‘ere the dawn of 2009. disappointment). In February we November 18. If you did not Our new monthly newsletter, had our AGM at Jack and Barbara receive a notice or have The Thistle , has had a very positive Dawsons' home in La Canada. Be mislaid it a copy may be reception from our members and it be noted that AGMs are more downloaded and printed has provided The Society with an like a ceilidhs! from the Saint Andrew’s While New Year’s Eve is effective method to communicate In May, there was our annual Society website: celebrated around the world, with and inform our members. The reception for new members, www.saintandrewsla.org. the Scots have a long rich Thistle is also mailed to an ever hosted by our Membership Chair Membership dues are the heritage associated with this growing list of sister organizations Vickie Pushee at her home in society’s principal form of celebration—and have their own accross the country and overseas, Brentwood. -

National Sample from the 1851 Census of Great Britain List of Sample Clusters

NATIONAL SAMPLE FROM THE 1851 CENSUS OF GREAT BRITAIN LIST OF SAMPLE CLUSTERS The listing is arranged in four columns, and is listed in cluster code order, but other orderings are available. The first column gives the county code; this code corresponds with the county code used in the standardised version of the data. An index of the county codes forms Appendix 1 The second column gives the cluster type. These cluster types correspond with the stratification parameter used in sampling and have been listed in Background Paper II. Their definitions are as follows: 11 English category I 'Communities' under 2,000 population 12 Scottish category I 'Communities' under 2,000 population 21 Category IIA and VI 'Towns' and Municipal Boroughs 26 Category IIB Parliamentary Boroughs 31 Category III 'Large non-urban communities' 41 Category IV Residual 'non-urban' areas 51 Category VII Unallocable 'urban' areas 91 Category IX Institutions The third column gives the cluster code numbers. This corresponds to the computing data set name, except that in the computing data set names the code number is preceded by the letters PAR (e.g. PAR0601). The fourth column gives the name of the cluster community. It should be noted that, with the exception of clusters coded 11,12 and 91, the cluster unit is the enumeration district and not the whole community. Clusters coded 11 and 12, however, correspond to total 'communities' (see Background Paper II). Clusters coded 91 comprise twenty successive individuals in every thousand, from a list of all inmates of institutions concatenated into a continuous sampling frame; except that 'families' are not broken, and where the twenty individuals come from more than one institution, each institution forms a separate cluster. -

John Buchan (1875-1940)

JOHN BUCHAN (1875-1940) John Buchan was born on 26 August 1875 in Perth, Scotland. The eldest son of a Free Church of Scotland minister (also named John) and his wife, Helen Jane Masterton, Buchan gained considerable fame as a creative writer and historian. He also devoted major portions of his career to the law, publishing, and government. For 12 years beginning in 1876, Buchan lived at Pathhead, on the east coast of Scotland, where his father served as minister at the West Church. In 1888, the family moved to Glasgow, where Buchan’s father began leading the congregation of the John Knox Free Church in the Gorbals – a working-class neighbourhood south of the Clyde. John Buchan. Photograph, 1911. Queen’s University Archive. Buchan studied at Hutchesons’ Grammar School until 1892, at which time he won a John Clark £30 bursary to enter Glasgow University. “I suppose I was a natural story-teller” (Memory, 193), Buchan reflected towards the end of his life. His first concerted literary efforts began during his years at Glasgow. Balancing academic pursuits with personal writing projects, Buchan made time to 1 contribute numerous articles and stories to periodicals, including Blackwood’s, Macmillan’s, and the Gentleman’s Magazine (which printed his first article, “Angling in Still Waters,” in August 1893). During this period, Buchan also edited Francis Bacon’s Essays and Apothegms (1894) and wrote his first novel, Sir Quixote of the Moors (1895). Buchan dedicated the latter to Gilbert Murray, a Glasgow professor who had a profound influence on his knowledge of Classical literature and philosophy. -

New Stock April 2021 – Remaining Books Reduced 9905 Chambers's

New stock April 2021 – remaining books reduced 9905 Chambers’s Journal, March 1925 The novel John Macnab was published by Hodder & Stoughton in July 1925 having been serialised in Chambers’s Journal from December 1924 to July 1925, This issue includes parts of chapters 5 and 7 and the whole of chapter 6, under the title John Macnab: A Comedy for Poachers. Small splits at the ends of the spine and some corners creased. £4 9904 Chambers’s Journal, Feb-July 1934 JB’s novel The Free Fishers was published in book form by Hodder & Stoughton in book form in June 1934. However, it was also serialised in Chambers’s Journal (monthly) from January to July 1934. This small collection includes the February to July issues only, thus missing the first part of the serialisation which covered chapters 1-3. The journals are in fair condition, mostly with some wear to the spines and creased covers. The rear cover of the May issue is missing and the last leaf of that issue is detached but loose. £25 9892 John Buchan Society memorabilia In October 2004 the John Buchan Society organised a visit by members of the Society to Canada. This small collection of memorabilia is partly (but not wholly) related to this visit. Programme of the visit to the WD Jordan Special Collections & Queen’s University Archives Menu card for dinner at the Fairmont Chateau Laurier, 18 Oct 2004 Photograph of JB taken by Lafayette, thought to be a Canadian photographer. Postcard photograph of a bronze bust of JB by Thomas Clapperton, 1935 The Lafayette photograph is lightly soiled at the margins; the other items are in very good condition. -

The Continuation, Breadth, and Impact of Evangelicalism in the Church of Scotland, 1843-1900

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. The Continuation, Breadth, and Impact of Evangelicalism in the Church of Scotland, 1843-1900 Andrew Michael Jones A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh, New College In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Edinburgh, United Kingdom 2018 ii Declaration This thesis has been composed by the candidate and is the candidate’s own work. Andrew M. Jones PhD Candidate iii Acknowledgements The research, composition, and completion of this thesis would have been impossible without the guidance and support of innumerable individuals, institutions, and communities. My primary supervisor, Professor Stewart J. Brown, provided expert historical knowledge, timely and lucid editorial insights, and warm encouragement from start to finish. My secondary supervisor, Dr. James Eglinton, enhanced my understanding of key cultural and theological ideas, offered wise counsel over endless cups of coffee, and reminded me to find joy and meaning in the Ph.D. -

Exquisite Clutter: Material Culture and the Scottish Reinvention of the Adventure Narrative

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2016 Exquisite Clutter: Material Culture and the Scottish Reinvention of the Adventure Narrative Rebekah C. Greene University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Greene, Rebekah C., "Exquisite Clutter: Material Culture and the Scottish Reinvention of the Adventure Narrative" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 438. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/438 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXQUISITE CLUTTER: MATERIAL CULTURE AND THE SCOTTISH REINVENTION OF THE ADVENTURE NARRATIVE BY REBEKAH C. GREENE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2016 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF REBEKAH C. GREENE APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Carolyn Betensky Ryan Trimm William Krieger Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2016 ABSTRACT EXQUISITE CLUTTER: MATERIAL CULTURE AND THE SCOTTISH REINVENTION OF THE ADVENTURE NARRATIVE BY REBEKAH C. GREENE Exquisite Clutter examines the depiction of material culture in adventures written by Scottish authors Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, and John Buchan. Throughout, these three authors use depictions of material culture in the adventure novel to begin formulating a critique about the danger of becoming overly comfortable in a culture where commodities are widely available. In these works, objects are a way to examine the complexities of character and to more closely scrutinize a host of personal anxieties about contact with others, changing societal roles, and one’s own place in the world.