Survival-Associated Metabolic Genes in Colon and Rectal Cancers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alzheimer's Disease Protective P522R Variant of PLCG2

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.27.059600; this version posted April 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. The Alzheimer’s disease protective P522R variant of PLCG2, consistently enhances stimulus-dependent PLCγ2 activation, depleting substrate and altering cell function. Emily Maguire #1, Georgina E. Menzies#1, Thomas Phillips#1, Michael Sasner2, Harriet M. Williams2, Magdalena A. Czubala3, Neil Evans1, Emma L Cope4, Rebecca Sims5, Gareth R. Howell2, Emyr Lloyd-Evans4, Julie Williams†1,5, Nicholas D. Allen†4 and Philip R. Taylor†*1,3. 1 UK Dementia Research Institute at Cardiff, Hadyn Ellis Building, Maindy Road, Cardiff, CF24 4HQ, Wales, UK. 2 The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04660, USA. 3 Systems Immunity University Research Institute, Tenovus Building, Heath Park, Cardiff CF 14 4XN, Wales, UK. 4 School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Museum Avenue, Cardiff, CF10 3AX. 5 MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics & Genomics, Hadyn Ellis Building, Maindy Road, Cardiff, CF24 4HQ, Wales, UK. #†These authors contributed equally *To whom correspondence should be addressed (lead contact): Prof Philip R. Taylor; Tel: +44(0)2920687328; Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Recent genome-wide association studies of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have identified variants implicating immune pathways in disease development. A rare coding variant of PLCG2, which encodes PLCγ2, shows a significant protective effect for AD (rs72824905, P522R, P=5.38x10-10, Odds Ratio = 0.68). -

Lysophosphatidic Acid and Its Receptors: Pharmacology and Therapeutic Potential in Atherosclerosis and Vascular Disease

JPT-107404; No of Pages 13 Pharmacology & Therapeutics xxx (2019) xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pharmacology & Therapeutics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pharmthera Lysophosphatidic acid and its receptors: pharmacology and therapeutic potential in atherosclerosis and vascular disease Ying Zhou a, Peter J. Little a,b, Hang T. Ta a,c, Suowen Xu d, Danielle Kamato a,b,⁎ a School of Pharmacy, University of Queensland, Pharmacy Australia Centre of Excellence, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102, Australia b Department of Pharmacy, Xinhua College of Sun Yat-sen University, Tianhe District, Guangzhou 510520, China c Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia d Aab Cardiovascular Research Institute, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, NY 14642, USA article info abstract Available online xxxx Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a collective name for a set of bioactive lipid species. Via six widely distributed G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), LPA elicits a plethora of biological responses, contributing to inflammation, Keywords: thrombosis and atherosclerosis. There have recently been considerable advances in GPCR signaling especially Lysophosphatidic acid recognition of the extended role for GPCR transactivation of tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase growth factor G-protein coupled receptors receptors. This review covers LPA signaling pathways in the light of new information. The use of transgenic and Atherosclerosis gene knockout animals, gene manipulated cells, pharmacological LPA receptor agonists and antagonists have Gproteins fi β-arrestins provided many insights into the biological signi cance of LPA and individual LPA receptors in the progression Transactivation of atherosclerosis and vascular diseases. -

Silencing of Phosphoinositide-Specific

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 34: 4069-4076 (2014) Silencing of Phosphoinositide-specific Phospholipase C ε Remodulates the Expression of the Phosphoinositide Signal Transduction Pathway in Human Osteosarcoma Cell Lines VINCENZA RITA LO VASCO1, MARTINA LEOPIZZI2, DANIELA STOPPOLONI3 and CARLO DELLA ROCCA2 Departments of 1Sense Organs , 2Medicine and Surgery Sciences and Biotechnologies and 3Biochemistry Sciences “A. Rossi Fanelli”, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy Abstract. Background: Ezrin, a member of the signal transduction pathway (5). The reduction of PIP2 ezrin–radixin–moesin family, is involved in the metastatic induces ezrin dissociation from the plasma membrane (6). spread of osteosarcoma. Ezrin binds phosphatydil inositol-4,5- The levels of PIP2 are regulated by the PI-specific bisphosphate (PIP2), a crucial molecule of the phospholipase C (PI-PLC) family (7), constituting thirteen phosphoinositide signal transduction pathway. PIP2 levels are enzymes divided into six sub-families on the basis of amino regulated by phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PI- acid sequence, domain structure, mechanism of recruitment PLC) enzymes. PI-PLCε isoform, a well-characterized direct and tissue distribution (7-15). PI-PLCε, a direct effector of effector of rat sarcoma (RAS), is at a unique convergence RAS (14-15), might be the point of convergence for the point for the broad range of signaling pathways that promote broad range of signalling pathways that promote the RAS GTPase-mediated signalling. Materials and Methods. By RASGTPase-mediated signalling (16). using molecular biology methods and microscopic analyses, In previous studies, we suggested a relationship between we analyzed the expression of ezrin and PLC genes after PI-PLC expression and ezrin (17-18). -

The Autotaxin–Lysophosphatidic Acid Axis Modulates Histone Acetylation and Gene Expression During Oligodendrocyte Differentiation

The Journal of Neuroscience, August 12, 2015 • 35(32):11399–11414 • 11399 Cellular/Molecular The Autotaxin–Lysophosphatidic Acid Axis Modulates Histone Acetylation and Gene Expression during Oligodendrocyte Differentiation Natalie A. Wheeler,1 James A. Lister,2 and Babette Fuss1 Departments of 1Anatomy and Neurobiology and 2Human and Molecular Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia 23298 During development, oligodendrocytes (OLGs), the myelinating cells of the CNS, undergo a stepwise progression during which OLG progenitors, specified from neural stem/progenitor cells, differentiate into fully mature myelinating OLGs. This progression along the OLG lineage is characterized by well synchronized changes in morphology and gene expression patterns. The latter have been found to be particularly critical during the early stages of the lineage, and they have been well described to be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, especially by the activity of the histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2. The data presented here identify the extracellular factor autotaxin (ATX) as a novel upstream signal modulating HDAC1/2 activity and gene expression in cells of the OLG lineage. Using the zebrafish as an in vivo model system as well as rodent primary OLG cultures, this functional property of ATX was found to be mediated by its lysophospholipase D (lysoPLD) activity, which has been well characterized to generate the lipid signaling molecule lysophosphatidic acid (LPA). More specifically, the lysoPLD activity of ATX was found to modulate HDAC1/2 regulated gene expression during a time window coinciding with the transition from OLG progenitor to early differentiating OLG. In contrast, HDAC1/2 regulated gene expression during the transition from neural stem/progenitor to OLG progenitor appeared unaffected by ATX and its lysoPLD activity. -

Plasma Lipidome Is Dysregulated in Alzheimer's Disease and Is

Liu et al. Translational Psychiatry (2021) 11:344 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01362-2 Translational Psychiatry ARTICLE Open Access Plasma lipidome is dysregulated in Alzheimer’s disease and is associated with disease risk genes Yue Liu1,2, Anbupalam Thalamuthu1, Karen A. Mather1,3, John Crawford1, Marina Ulanova1, Matthew Wai Kin Wong1, Russell Pickford4, Perminder S. Sachdev 1,5 and Nady Braidy 1,6 Abstract Lipidomics research could provide insights of pathobiological mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. This study explores a battery of plasma lipids that can differentiate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients from healthy controls and determines whether lipid profiles correlate with genetic risk for AD. AD plasma samples were collected from the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study (MAS) Sydney, Australia (aged range 75–97 years; 51.2% male). Untargeted lipidomics analysis was performed by liquid chromatography coupled–mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). We found that several lipid species from nine lipid classes, particularly sphingomyelins (SMs), cholesterol esters (ChEs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PIs), phosphatidylinositols (PIs), and triglycerides (TGs) are dysregulated in AD patients and may help discriminate them from healthy controls. However, when the lipid species were grouped together into lipid subgroups, only the DG group was significantly higher in AD. ChEs, SMs, and TGs resulted in good classification accuracy using the Glmnet algorithm (elastic net penalization for the generalized linear model [glm]) with more than 80% AUC. In general, group lipids and the lipid subclasses LPC and PE had less classification accuracy compared to the other subclasses. We also found significant increases in SMs, PIs, and the LPE/PE ratio in human U251 astroglioma cell lines exposed to pathophysiological concentrations of oligomeric Aβ42. -

Antibody Response Cell Antigen Receptor Signaling And

Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptor 5 Inhibits B Cell Antigen Receptor Signaling and Antibody Response This information is current as Jiancheng Hu, Shannon K. Oda, Kristin Shotts, Erin E. of September 24, 2021. Donovan, Pamela Strauch, Lindsey M. Pujanauski, Francisco Victorino, Amin Al-Shami, Yuko Fujiwara, Gabor Tigyi, Tamas Oravecz, Roberta Pelanda and Raul M. Torres J Immunol 2014; 193:85-95; Prepublished online 2 June 2014; Downloaded from doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300429 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/193/1/85 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2014/05/31/jimmunol.130042 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Material 9.DCSupplemental References This article cites 63 articles, 17 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/193/1/85.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. by guest on September 24, 2021 • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2014 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptor 5 Inhibits B Cell Antigen Receptor Signaling and Antibody Response Jiancheng Hu,*,1,2 Shannon K. -

Description Cy5 LG Cy3 MI Ratio(Cy3/Cy5) C9orf135

Supplementary Table S2. DNA microarray dataset of top 30 differentially expressed genes and housekeeping genes Up-regulated in SI cancer cells Symbol Description Cy5_LG Cy3_MI Ratio(Cy3/Cy5) C9orf135 Uncharacterized protein C9orf135 1.37 307.8 224.3 KIAA1245 Notch homolog 2 N-terminal like protein 1.82 406.8 223.6 APITD1 Centromere protein S (CENP-S) 2.56 560.3 218.7 PPIL6 Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase-like 6 1.85 343.0 185.7 MYCBP2 Probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MYCBP2 2.01 332.1 165.6 ANGPTL4 Angiopoietin-related protein 4 precursor 10.26 1500.1 146.3 C10orf79 Novel protein (Fragment) 2.86 415.5 145.5 NP_653323.1 KPL2 protein isoform 2 1.82 257.5 141.6 ZNF345 Zinc finger protein 345 1.58 215.7 136.8 SIX1 Homeobox protein SIX1 1.59 216.1 136.0 KLHL7 Kelch-like protein 7 1.91 254.4 133.3 TBX1 T-box transcription factor TBX1 1.57 209.0 133.1 PAG1 Phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains 1 2.19 290.9 133.0 NOL12 Nucleolar protein 12 1.61 203.7 126.5 ZNF606 Zinc finger protein 606 2.12 267.7 126.0 NFKBIE NF-kappa-B inhibitor epsilon 5.28 658.3 124.7 ZMYND10 Zinc finger MYND domain-containing protein 10 6.85 835.5 121.9 hCG_23177 - 14.94 1758.9 117.7 KIF3A Kinesin-like protein KIF3A 1.94 224.9 116.1 Q9C0K3_HUMAN Actin-related protein Arp11 3.38 368.0 108.9 NP_056263.1 DPCD protein 2.61 270.5 103.7 GBP1 Interferon-induced guanylate-binding protein 1 1.46 149.1 102.3 NP_660151.2 NAD(P) dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like 1.35 137.4 101.5 NP_689672.2 CDNA FLJ90761 fis, clone THYRO1000099 3.68 372.5 -

Supplementary Table 1 List of 335 Genes Differentially Expressed Between Primary (P) and Metastatic (M) Tumours

Supplementary Table 1 List of 335 genes differentially expressed between primary (P) and metastatic (M) tumours Spot ID I.M.A.G.E. UniGene Symbol Name Clone ID Cluster 296529 296529 In multiple clusters 731356 731356 Hs.140452 M6PRBP1 mannose-6-phosphate receptor binding protein 1 840942 840942 Hs.368409 HLA-DPB1 major histocompatibility complex, class II, DP beta 1 142122 142122 Hs.115912 AFAP actin filament associated protein 1891918 1891918 Hs.90073 CSE1L CSE1 chromosome segregation 1-like (yeast) 1323432 1323432 Hs.303154 IDS iduronate 2-sulfatase (Hunter syndrome) 788566 788566 Hs.80296 PCP4 Purkinje cell protein 4 591281 591281 Hs.80680 MVP major vault protein 815530 815530 Hs.172813 ARHGEF7 Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 7 825312 825312 Hs.246310 ATP5J ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F0 complex, subunit F6 784830 784830 Hs.412842 C10orf7 chromosome 10 open reading frame 7 840878 840878 Hs.75616 DHCR24 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase 669443 669443 Hs.158195 HSF2 heat shock transcription factor 2 2485436 2485436 Data not found 82903 82903 Hs.370937 TAPBP TAP binding protein (tapasin) 771258 771258 Hs.85258 CD8A CD8 antigen, alpha polypeptide (p32) 85128 85128 Hs.8986 C1QB complement component 1, q subcomponent, beta polypeptide 41929 41929 Hs.39252 PICALM phosphatidylinositol binding clathrin assembly protein 148469 148469 Hs.9963 TYROBP TYRO protein tyrosine kinase binding protein 415145 415145 Hs.1376 HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 810017 810017 Hs.179657 PLAUR plasminogen activator, -

Supplementary Table S2

1-high in cerebrotropic Gene P-value patients Definition BCHE 2.00E-04 1 Butyrylcholinesterase PLCB2 2.00E-04 -1 Phospholipase C, beta 2 SF3B1 2.00E-04 -1 Splicing factor 3b, subunit 1 BCHE 0.00022 1 Butyrylcholinesterase ZNF721 0.00028 -1 Zinc finger protein 721 GNAI1 0.00044 1 Guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), alpha inhibiting activity polypeptide 1 GNAI1 0.00049 1 Guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), alpha inhibiting activity polypeptide 1 PDE1B 0.00069 -1 Phosphodiesterase 1B, calmodulin-dependent MCOLN2 0.00085 -1 Mucolipin 2 PGCP 0.00116 1 Plasma glutamate carboxypeptidase TMX4 0.00116 1 Thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 4 C10orf11 0.00142 1 Chromosome 10 open reading frame 11 TRIM14 0.00156 -1 Tripartite motif-containing 14 APOBEC3D 0.00173 -1 Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3D ANXA6 0.00185 -1 Annexin A6 NOS3 0.00209 -1 Nitric oxide synthase 3 SELI 0.00209 -1 Selenoprotein I NYNRIN 0.0023 -1 NYN domain and retroviral integrase containing ANKFY1 0.00253 -1 Ankyrin repeat and FYVE domain containing 1 APOBEC3F 0.00278 -1 Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3F EBI2 0.00278 -1 Epstein-Barr virus induced gene 2 ETHE1 0.00278 1 Ethylmalonic encephalopathy 1 PDE7A 0.00278 -1 Phosphodiesterase 7A HLA-DOA 0.00305 -1 Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DO alpha SOX13 0.00305 1 SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 13 ABHD2 3.34E-03 1 Abhydrolase domain containing 2 MOCS2 0.00334 1 Molybdenum cofactor synthesis 2 TTLL6 0.00365 -1 Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family, member 6 SHANK3 0.00394 -1 SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 ADCY4 0.004 -1 Adenylate cyclase 4 CD3D 0.004 -1 CD3d molecule, delta (CD3-TCR complex) (CD3D), transcript variant 1, mRNA. -

Technical Note, Appendix: an Analysis of Blood Processing Methods to Prepare Samples for Genechip® Expression Profiling (Pdf, 1

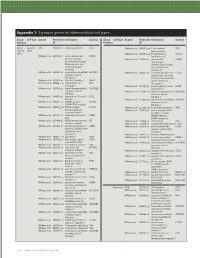

Appendix 1: Signature genes for different blood cell types. Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Fraction ID Fraction ID Mono- Lympho- GSK 203547_at CD4 antigen (p55) CD4 Whitney et al. 209813_x_at T cell receptor TRG nuclear cytes gamma locus cells Whitney et al. 209995_s_at T-cell leukemia/ TCL1A Whitney et al. 203104_at colony stimulating CSF1R lymphoma 1A factor 1 receptor, Whitney et al. 210164_at granzyme B GZMB formerly McDonough (granzyme 2, feline sarcoma viral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte- (v-fms) oncogene associated serine homolog esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203290_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQA1 Whitney et al. 210321_at similar to granzyme B CTLA1 complex, class II, (granzyme 2, cytotoxic DQ alpha 1 T-lymphocyte-associated Whitney et al. 203413_at NEL-like 2 (chicken) NELL2 serine esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203828_s_at natural killer cell NK4 (H. sapiens) transcript 4 Whitney et al. 212827_at immunoglobulin heavy IGHM Whitney et al. 203932_at major histocompatibility HLA-DMB constant mu complex, class II, Whitney et al. 212998_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB1 DM beta complex, class II, Whitney et al. 204655_at chemokine (C-C motif) CCL5 DQ beta 1 ligand 5 Whitney et al. 212999_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB Whitney et al. 204661_at CDW52 antigen CDW52 complex, class II, (CAMPATH-1 antigen) DQ beta 1 Whitney et al. 205049_s_at CD79A antigen CD79A Whitney et al. 213193_x_at T cell receptor beta locus TRB (immunoglobulin- Whitney et al. 213425_at Homo sapiens cDNA associated alpha) FLJ11441 fis, clone Whitney et al. 205291_at interleukin 2 receptor, IL2RB HEMBA1001323, beta mRNA sequence Whitney et al. -

Time Resolved Quantitative Phosphoproteomics Reveals Distinct Patterns of SHP2

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/598664; this version posted April 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Time resolved quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals distinct patterns of SHP2 dependence in EGFR signaling Vidyasiri Vemulapalli1,2, Lily Chylek3, Alison Erickson4, Jonathan LaRochelle1,2, Kartik Subramanian3, Morvarid Mohseni5, Matthew LaMarche5, Michael G. Acker5, Peter K. Sorger3, Steven P. Gygi4, and Stephen C. Blacklow1,2* 1Department of Cancer Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Boston, MA 02115, USA 2Department of Biological Chemistry & Molecular Pharmacology, Blavatnik Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA 3Laboratory of Systems Pharmacology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA 4Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA 5Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/598664; this version posted April 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract SHP2 is a protein tyrosine phosphatase that normally potentiates intracellular signaling by growth factors, antigen receptors, and some cytokines; it is frequently mutated in childhood leukemias and other cancers. Here, we examine the role of SHP2 in the responses of breast cancer cells to EGF by monitoring phosphoproteome dynamics when SHP2 is allosterically inhibited by the small molecule SHP099. -

Phosphodiesterase (PDE)

Phosphodiesterase (PDE) Phosphodiesterase (PDE) is any enzyme that breaks a phosphodiester bond. Usually, people speaking of phosphodiesterase are referring to cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, which have great clinical significance and are described below. However, there are many other families of phosphodiesterases, including phospholipases C and D, autotaxin, sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase, DNases, RNases, and restriction endonucleases, as well as numerous less-well-characterized small-molecule phosphodiesterases. The cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases comprise a group of enzymes that degrade the phosphodiester bond in the second messenger molecules cAMP and cGMP. They regulate the localization, duration, and amplitude of cyclic nucleotide signaling within subcellular domains. PDEs are therefore important regulators ofsignal transduction mediated by these second messenger molecules. www.MedChemExpress.com 1 Phosphodiesterase (PDE) Inhibitors, Activators & Modulators (+)-Medioresinol Di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (R)-(-)-Rolipram Cat. No.: HY-N8209 ((R)-Rolipram; (-)-Rolipram) Cat. No.: HY-16900A (+)-Medioresinol Di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside is a (R)-(-)-Rolipram is the R-enantiomer of Rolipram. lignan glucoside with strong inhibitory activity Rolipram is a selective inhibitor of of 3', 5'-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic AMP) phosphodiesterases PDE4 with IC50 of 3 nM, 130 nM phosphodiesterase. and 240 nM for PDE4A, PDE4B, and PDE4D, respectively. Purity: >98% Purity: 99.91% Clinical Data: No Development Reported Clinical Data: No Development Reported Size: 1 mg, 5 mg Size: 10 mM × 1 mL, 10 mg, 50 mg (R)-DNMDP (S)-(+)-Rolipram Cat. No.: HY-122751 ((+)-Rolipram; (S)-Rolipram) Cat. No.: HY-B0392 (R)-DNMDP is a potent and selective cancer cell (S)-(+)-Rolipram ((+)-Rolipram) is a cyclic cytotoxic agent. (R)-DNMDP, the R-form of DNMDP, AMP(cAMP)-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE) binds PDE3A directly.