The U.S. Army on Kaua'i, 1909—1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

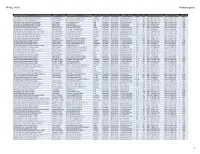

2019 Hawaii Regional Scholastic Art Award Nominees 1

2019 Hawaii Regional Scholastic Art Award Nominees 1 SCHOOL NAME TITLE CATEGORY AWARD STUDENT FIRST NAME STUDENT LAST NAME EDUCATOR FIRST NAME EDUCATOR LAST NAME AMERICAN VISIONS Aiea Intermediate School RoBots vs Monsters Digital Art Silver Key Patton Courie Eizen Ramones Aiea Intermediate School roBot vs. monster Digital Art HonoraBle Mention layla wilson Eizen Ramones Aliamanu Middle School Purple hair Painting Silver Key Aliyah Varela Ted Uratani Aliamanu Middle School Escher is great Drawing and Illustration HonoraBle Mention Kierra Birt Ted Uratani Aliamanu Middle School Curved world Drawing and Illustration HonoraBle Mention Ella Freeman Ted Uratani Aliamanu Middle School Pink Sky Painting HonoraBle Mention Breah Lang Ted Uratani Aliamanu Middle School White Wash Drawing and Illustration HonoraBle Mention Annie Pham Ted Uratani Aliamanu Middle School Curly hair Drawing and Illustration HonoraBle Mention Joanna Stellard Ted Uratani Aliamanu Middle School Houses on hills Drawing and Illustration HonoraBle Mention Jiyanah Sumajit Ted Uratani Asia Pacific International School No Title Drawing and Illustration Gold Key Rylan Ascher Erin Hall Farrington High School Beauty Film & Animation Gold Key Emerald Pearl BaBaran Charleen Ego Farrington High School My Voice Are In My Art Film & Animation HonoraBle Mention Mona-Lynn Contaoi Charleen Ego Farrington High School Flip Photography HonoraBle Mention Alyia Boaz Aljon Tacata Farrington High School Rivals Photography HonoraBle Mention Jaymark Juan Aljon Tacata Farrington High School Flip -

Hawaiʻi's Big Five

Hawaiʻi’s Big Five (Plus 2) “By 1941, every time a native Hawaiian switched on his lights, turned on the gas or rode on a street car, he paid a tiny tribute into Big Five coffers.” (Alexander MacDonald, 1944) The story of Hawaii’s largest companies dominates Hawaiʻi’s economic history. Since the early/mid- 1800s, until relatively recently, five major companies emerged and dominated the Island’s economic framework. Their common trait: they were focused on agriculture - sugar. They became known as the Big Five: C. Brewer (1826;) Theo H. Davies (1845;) Amfac - starting as Hackfeld & Company (1849;) Castle & Cooke (1851) and Alexander & Baldwin (1870.) C. Brewer & Co. Amfac Founded: October 1826; Capt. James Hunnewell Founded: 1849; Heinrich Hackfeld and Johann (American Sea Captain, Merchant; Charles Carl Pflueger (German Merchants) Brewer was American Merchant) Incorporated: 1897 (H Hackfeld & Co;) American Incorporated: February 7, 1883 Factors Ltd, 1918 Theo H. Davies & Co. Castle & Cooke Founded: 1845; James and John Starkey, and Founded: 1851; Samuel Northrup Castle and Robert C. Janion (English Merchants; Theophilus Amos Starr Cooke (American Mission Secular Harris Davies was Welch Merchant) Agents) Incorporated: January 1894 Incorporated: 1894 Alexander & Baldwin Founded: 1870; Samuel Thomas Alexander & Henry Perrine Baldwin (American, Sons of Missionaries) Incorporated: 1900 © 2017 Ho‘okuleana LLC The Making of the Big Five Some suggest they were started by the missionaries. Actually, only Castle & Cooke has direct ties to the mission. However, Castle ran the ‘depository’ and Cooke was a teacher, neither were missionary ministers. Alexander & Baldwin were sons of missionaries, but not a formal part of the mission. -

Sugar Maui Hawaii Final 6 2014

Report: Excursion on Sugar Production in Maui, Hawaii, June 03 – 06, 2014 Source: Kern, M., 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Sugar Cane Museum, Maui, Hawaii, 6/2014 Origin and Migration of Sugar Cane to Hawaii Source: Kern, M., 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Sugar Cane Museum, Maui, Hawaii, 6/2014 Sun, Wind and Water Water for the Fields N Wind Dry Plain Source: Kern, M., 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Sugar Cane Museum, Maui, Hawaii, 6/2014 Source: Kern, M., 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Sugar Cane Museum, Maui, Hawaii, 6/2014 Source: Kern, M., 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Sugar Cane, Maui, Hawaii, 6/2014 ° Sugar cane is a giant grass producing stalkes that range from 8 to 30 feet long. ° Stalks are too tall to stand upright so they fell into each other and form tangled masses. ° In Hawaii, sugar cane takes twlo years to mature. From one acre of cane, 12 tons of raw sugar may be produced. This amounts to 22,465 pounds of refined sugar. Source: Kern, M., 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Sugar Cane Train , Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii, 6/2014 Source: Kern, M., 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company (HC&S), 2014: Vision Source: http://hcsugar.com . 6/2014 Dr. Manfred Kern Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company (HC&S), 2014: History The Beginning ° Well over a century old, HC&S has grown from a small Maui sugarcane plantation founded by two childhood friends into one of the worlds most advanced and productive sugar businesses. ° Augmenting their original investment in 12 acres below Makawao, Maui, with the acquisition of an additional 559 acres, Samuel Thomas Alexander and Henry Perrine Baldwin planted their first sugarcane crop in 1870 on their newly established Alexander and Baldwin plantation. -

2Nd Grade Pre Visit Packet

Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum Education Program 2nd Grade Teacher Resource Packet P.O. Box 125, Puunene, Hawaii 96784 Phone: 808-871-8058 Fax: 808-871-4321 [email protected] http://www.sugarmuseum.com/outreach/#education https://www.facebook.com/AlexanderBaldwinSugarMuseum/ The Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum is an 501(c)(3) independent non-profit organization whose mission is to preserve and present the history and heritage of the sugar industry, and the multiethnic plantation life it engendered. All rights reserved. In accordance with the US Copyright Act, the scanning, uploading and electronic sharing of any part of these materials constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the Museum’s intellectual property. For more information about the legal use of these materials, contact the Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum at PO Box 125, Puunene, Hawaii 96784. Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum Education Program 2nd Grade Teacher Resource Packet Table of Contents Education Program Statement Overview: • Reservations • Tour Size & Length • Admission Fee • Chaperone Requirements • Check In • Lunch • Rain • Rules Nametags Gallery Map Outdoor Map of Activity Stations* Education Standards Vocabulary Words The Process of Sugar Explained One Armed Baldwin Story Greetings in Different Languages *For a complete description of outdoor activities, see “Second Grade Activities Descriptions” or “Chaperone Activities Descriptions” at our website, http://www.sugarmuseum.com/outreach/#education Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum Education Program Statement What we do As the primary source of information on the history of sugar on Maui, the Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum responds to the educational needs of the community by developing programs that interpret the history of the sugar industry and the cultural heritage of multiethnic plantation life; providing online learning materials in an historic setting; providing learning materials online, and supporting educators’ teaching goals. -

SCHOOL CHURCH 1. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Elementary School Fellowship Bible Church 2

SCHOOL CHURCH 1. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Elementary School Fellowship Bible Church 2. Aiea Elementary School Grace Bible Church West Oahu 3. Aiea Elementary School New Life Samoan Assembly of God 4. Aiea High School Amataga Fou Church 5. Aiea High School Victory Aiea 6. Ala Wai Elementary School New Hope South Shore 7. Ali'iolani Elementary School Grace Christian Community Church 8. Aliamanu Elementary School Island Family Christian Church 9. Aliamanu Elementary School Soul'd Out Christian Center 10. Alvah Scott Elementary School New Hope Oahu at Aiea 11. Blanche Pope Elementary School Joyful Community Church 12. Chiefess Kamakahelei Middle School God Can Christian Center 13. Enchanted Lake Elementary School “The Wave” Revival Christian Fellowship 14. Ewa Elementary School Defenders of the Christian Faith Church 15. Ewa Makai Middle School Grace Bible Church West Oahu 16. Governor Samuel Wilder King Intermediate School Christ-Centered Life Mission 17. Governor Samuel Wilder King Intermediate School Jesus is My Shepherd Church 18. Haha'ione Elementary School Hawaii Kai United Church of Christ 19. Haleiwa Elementary School New Hope Central Oahu 20. Hana High & Elementary School Kings Cathedral 21. Hanalei Elementary School Amazing Grace Church 22. Henry Perrine Baldwin High School Pentacostals of Maui (LUPC) 23. Henry Perrine Baldwin High School The Door Maui 24. Hokulani Elementary School Our Lady of Lourdes 25. Holomua Elementary School Hope Chapel West Side 26. Honoka'a High & Intermediate School King's Chapel Honokaa 27. Honowai Elementary School Life Changing Ministries 28. Iao Intermediate School Grace Bible Church Maui 29. Iliahi Elementary School New Hope Central Oahu Wahiawa 30. -

Accreditation Status of Hawaii Public Schools

WASC 0818 Hawaii update Complex Area Complex School Name SiteCity Status Category Type Grades Enroll NextActionYear-Type Next Self-study TermExpires Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Radford Complex Admiral Arthur W. Radford High School Honolulu Accredited Public School Comprehensive 9–12 1330 2020 - 3y Progress Rpt 2023 - 11th Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Radford Complex Admiral Chester W. Nimitz School Honolulu Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 689 2019 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2022 - 2nd Self-study 2022 Windward District-Castle-Kahuku Complex Castle Complex Ahuimanu Elementary School Kaneohe Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 301 2020 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2023 - 2nd Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea Elementary School Aiea Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 375 2020 - Mid-cycle 2-day 2023 - 2nd Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea High School Aiea Accredited Public School Comprehensive 9–12 1002 2019 - 10th Self-study 2019 - 10th Self-study 2019 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea Intermediate School Aiea Accredited Public School Comprehensive 7–8 607 2020 - 8th Self-study 2020 - 8th Self-study 2020 Windward District-Kailua-Kalaheo Complex Kalaheo Complex Aikahi Elementary School Kailua Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 487 2021 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2024 - 2nd Self-study 2024 Honolulu District-Farrington-Kaiser-Kalani Complex -

Doris Kahikilani Mossman Keppeler the Watumull

DORIS KAHIKILANI MOSSMAN KEPPELER THE WATUMULL FOUNDATION ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Doris Kahikilani Mossman Keppeler (1899 - 1972) The late Mrs. Keppeler, a noted Hawaiiana au thority, was born in Hana, Maui to William Lloyd and Louise Summer Miner Mossman. Her great-grand father Thomas James Mossman, a shipowner and cap tain, brought his wife and family to Hawaii to settle in 1849. Her grandfather William Frederic' Mossman moved to Maui as a young man and married Clara Mokomanic Rohrer, an American Indian who came to Maui at the age of fifteen with a group of Anglican missionaries to establish a mission which is now the Church of The Good Shepherd in Wailuku. Mrs. Keppeler was educated at Saint Andrew's Priory for Girls and graduated from the University of Hawaii in 1924. She began her teaching career at Hilo Intermediate School in 1924-25, then went to McKinley High School where she taught and served as counselor until her retirement in 196J. On July 28, 1925 she married Herbert Kealoha Keppeler who was then the chief engineer and sur veyor for the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate. Their children are John Paul II, Herbert Karl Bruss and Barbara Leinani Keppeler (Mrs. Larry L.) Bortles. Mrs. Keppeler was very active in the produc tion of Hawaiian pageants and parades for Kameha meha Day, Lei Day and Aloha Week, and received sev eral awards for her work in Hawaiiana. She relates her own and her family's history, as well as that of her husband, and discusses her many projects and knowledge of Hawaiiana. -

Maui's Mom & Pop Stores

Maui’s Mom & Pop Stores: The Aesthetic & Intrinsic Study of Multi-Generation & Family-Owned Businesses Kreig Kihara May 2013 Submitted towards the fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Architecture Degree School of Architecture University of Hawaii Doctorate Project Committee: Joyce M. Noe, Chairperson Maile Meyer William Chapman Maui’s Mom & Pop Stores: The Aesthetic & Intrinsic Study of Multi-Generation & Family-Owned Businesses Kreig Kihara May 2013 We certify that we have read this Doctorate Project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality in fulfillment as a Doctorate Project for the degree of Doctor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. Doctorate Project Committee Joyce M. Noe, Chairperson Maile Meyer William Chapman 2 Maui’s Mom & Pop Stores: The Aesthetic & Intrinsic Study of Multi-Generation & Family-Owned Businesses Kreig Kihara May 2013 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………………………………………..………..5 Background………………………………………………………………………..…………...6 Personal Experience Project Statement Research……………………………………………………………………….………………..9 Retail Mom & Pop Stores Qualities Of A Mom & Pop Store Owner Smart Growth Criteria Historic Integrity...........................................................................................................16 Introduction Seven Aspects of Integrity Mom & Pop Store Manifestation…..............................................................................22 Introduction Maui Early Immigration Sugar Industry The Role of -

H.B. No. a Bill for an Act

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES H.B. NO. A BILL FOR AN ACT RELATING TO CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS FOR THE BENEFIT OF THE EIGHTH REPRESENTATIVE DISTRICT. BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF HAWAII: 1 SECTION 1. The director of finance is authorized to issue 2 general obligation bonds in the sum of $15,223,240 or so much 3 thereof as may be necessary and the same sum or so much thereof 4 as may be necessary is appropriated for fiscal year 2021-2022 5 for the purpose of capital improvement projects for the eighth 6 representative district, as follows: 7 1. Henry Perrine Baldwin high school, Maui 8 Design and construction for campus wide 9 electrical system upgrades, ground and 10 site improvements, and equipment and 11 appurtenances. 12 Design $200,000 13 Construction $5,000,000 14 Total funding $5,200,000 15 The sum appropriated for this capital improvement project 16 shall be expended by the department of education. 2021—0650 HB HMSO—1 H.B. NO. 1 2. Henry Perrine Baldwin high school, Maui 2 Design and construction for reroof 3 gymnasium, including the installation 4 of six large fans in the gymnasium for 5 heat abatement; ground and site 6 improvements; and equipment and 7 appurtenances. 8 Design $203,240 9 Construction $2,200,000 10 Total funding $2,403,240 11 The sum appropriated for this capital improvement project 12 shall be expended by the department of education. 13 3. Henry Perrine Baldwin high school, Maui 14 Design and construction for 15 installation of air conditioning 16 systems in Buildings B, C, and D; 17 ground and site improvements; and 18 equipment and appurtenances. -

Annie Montague Alexander: Explorer, Naturalist, Philanthropist

RIANNA M. WILLIAMS Annie Montague Alexander: Explorer, Naturalist, Philanthropist KAMA'AINA ANNIE MONTAGUE ALEXANDER was a well-known and respected naturalist and explorer in several western states and a phil- anthropic leader in the development of two natural history museums at the University of California, Berkeley campus. She traveled the world for pleasure, knowledge, and the opportunity to collect natural history specimens that interested her. Over a period of forty-six years, she contributed approximately a million and a half dollars toward the support and endowment of the university's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and the Museum of Paleontology, contributing immeasur- ably to the teaching and research facilities of the University.1 CHILDHOOD Annie was the oldest daughter of Samuel Thomas Alexander and Martha Cooke Alexander of Maui. Samuel was the son of the Rever- end William Patterson Alexander and Mary Ann McKinney Alex- ander, who arrived in Hawai'i in 1832 in the Fifth Company of American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Samuel was born October 29, 1836, in a grass hut at Wai'oli in Hanalei, Kaua'i. When Samuel was seven his father was transferred to Maui, where he became the headmaster of Lahainaluna School and later manager of Previously published, Rianna M. Williams has returned to research and writing after nine years working in the historical area. A longtime student of Hawaiian history, she now vol- unteers at Bishop Museum. The Hawaiian Journal ofHistory, vol. 28 (1994) 114 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY 'Ulupalakua Ranch. It was at Lahaina, while young children, that Samuel and Henry Perrine Baldwin, son of the Reverend Dwight Baldwin, became friends; they later became business partners and brothers-in-law as well. -

State Qualifiers List 2018 Updates 3.28.18.Xlsx

Maui District State Qualifiers List Junior Documentary Entry # Title Students Teacher School A Rich Man's War, A Poor Man's Battle: New 1302 York City Draft Riots Cash Palma, Mathew Iverson Patricia Wurst Sacred Hearts School Lahaina The young Mans Opportunity: The Civilian 1304 Conservation Corps Alexis Nordblom Patricia Wurst Sacred Hearts School Lahaina Christopher Mueller, Patrick 1306 Leaving for Hope. Fall Of Saigon Doan Patricia Wurst Sacred Hearts School Lahaina Senior Documentary Entry # Title Students Teacher School Unintended Consequences…The Failed Christine Alonzo, Dona Mae 2301 Compromise to End Global Conflict B. Bio, Louise Dantes Janyce Omura Maui High School Conscientious Objectors of The Vietnam Jayboy Badua, Romelyn Joy 2302 War Tabangcura, Tiana-Lei Juan Janyce Omura Maui High School The Treaty of Paris (1898): The Basis of 2303 American Imperialism Gem Galapon, Lauryn Ige Wayne Feike Henry Perrine Baldwin High School Junior Exhibit Entry # Title Students Teacher School 1203 New Zealand's 2nd Class Citizens Benjamin Lolesio Patricia Wurst Sacred Hearts School Lahaina 1208 The Children's Union Sydney McCarney Patricia Wurst Sacred Hearts School Lahaina Devyn Gruber, Noelani 1210 The New York Draft Riots of 1863 Ligienza Patricia Wurst Sacred Hearts School Lahaina Social Conflict During War: Japanese 1214 American Internment Kaila Hendrickson Patricia Wurst Sacred Hearts School Lahaina Senior Exhibit Entry # Title Students Teacher School The Treaty of Versailles: When a Charles Hill, Johnel Torrejas, 2207 Compromise -

For IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 20, 2018 Alexander & Baldwin

For IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 20, 2018 Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum 3957 Hansen Road Puunene, HI 96784 Contact: Roslyn Lightfoot 808-871-8058 [email protected] GRANT AWARDED FOR SUGAR MUSEUM’S PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS Pu’unene, Maui, Hawaii – Alexander & Baldwin has awarded a $20,000 grant to the Sugar Museum. The grant will provide support for the core programs and projects of the Museum. The funds will be used towards the education program, marketing and community outreach programs. Museum Director Roslyn Lightfoot said, “We are very appreciative of this award. Through Alexander & Baldwin’s generous support, we are able to continue providing valuable services to the community.” The funding will assist the museum in the following areas: Education Program: Helps children learn about our sugar plantation heritage and how it helped shape our current society. Alexander & Baldwin has been supporting the transportation and operating costs for second-grade students since the inception of the program in 1990. Marketing: Operating costs for promoting the Museum through advertising as well as printing the “Passport to the Past,” which offers discounted admission to four island museums. Community Outreach: Delivers information to our neighborhoods through displays at festivals and other cultural events throughout the year. As a resource for the community, we provide cultural and community groups with loans of photographs and objects from our collection for their events, bulletin board space to promote their activities, and a venue for community meetings. About The Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum The Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum is an independent 501 (c) 3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving and presenting the history and heritage of the sugar industry and the multiethnic plantation life it engendered.