Now I've Become a Stranger in My Own Hometown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3947686048 Lp.Pdf

Bleiben in Breslau Potsdamer Jüdische Studien Herausgegeben von Th omas Brechenmacher und Christoph Schulte Bd. 3 Anja Schnabel Bleiben in Breslau Jüdische Selbstbehauptung und Sinnsuche in den Tagebüchern Willy Cohns 1933 bis 1941 Das Manuskript hat der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Potsdam 2016 als Dissertation vor- gelegen (Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Th omas Brechenmacher, Universität Potsdam, Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Norbert Conrads, Universität Stuttgart). Der Druck wurde ermöglicht durch die Axel Springer Stift ung, Berlin, und die Stift ung Irène Bollag-Herzheimer, Basel. Bibliografi sche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografi e; detaillierte bibliografi sche Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufb ar. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk, einschließlich aller seiner Teile, ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafb ar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfi lmungen, Verfi lmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung auf DVDs, CD-ROMs, CDs, Videos, in weiteren elektronischen Systemen sowie für Internet-Plattformen. © be.bra wissenschaft verlag GmbH Berlin-Brandenburg, 2018 KulturBrauerei Haus 2 Schönhauser Allee 37, 10435 Berlin [email protected] Lektorat: Matthias Zimmermann, Berlin Umschlag: typegerecht, Berlin Satz: ZeroSoft Schrift : Minion Pro 10/13pt Gedruckt in Deutschland ISBN 978-3-95410-203-7 www.bebra-wissenschaft .de Inhalt Einleitung. 7 Forschungsgegenstand – Festlegungen – Vorgehen. 8 Potenzial und Grenzen autobiografi scher Quellen . 13 Forschungsstand . 21 Gliederung . 26 Prolog: Annäherung an eine verschwundene Welt. 28 Biografi scher Rahmen . 31 Das Breslau Willy Cohns. 31 Lebensgeschichtliche Erfahrungen 1888–1932 . 37 Ein Kind im Kaiserreich . -

President Joachim Gauck on the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of National Socialism on 27 January 2015 in Berlin

The speech online: www.bundespraesident.de page 1 to 8 Federal President Joachim Gauck on the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of National Socialism on 27 January 2015 in Berlin Seventy years ago today, Red Army soldiers liberated the Auschwitz concentration camp. Nearly twenty years ago, the German Bundestag first convened to dedicate a day of remembrance to the victims of the Nazi regime. Roman Herzog, who was the Federal President at the time, insisted that remembrance had to continue forever. Without remembrance, he said, evil could not be overcome and no lessons could be learned for the future. Many prominent witnesses to this history have since spoken here before this House – survivors of concentration camps, ghettos or the underground resistance, as well as survivors of starved, besieged cities. In moving words, they have shared their fate with us. And they have spoken about the relationship between their own peoples and the German people – a relationship in which nothing was the same after the atrocities committed under Nazi rule. Permit me to begin today with a witness account too – these are, however, the words of a witness who did not survive the Holocaust. His diaries did survive, though, and were published, albeit not until 65 years after his death. I am referring to Willy Cohn. Willy Cohn came from a prosperous merchant family and taught high school in what was then Breslau. He was an Orthodox Jew, and he was deeply connected with German culture and history. He had earned the Iron Cross for his distinguished service in the First World War. -

Memoirs of a Political Education

best of times, worst of times the tauber institute for the study of eu ro pe an jewry series Jehuda Reinharz, General Editor Sylvia Fuks Fried, Associate Editor The Tauber Institute Series is dedicated to publishing compelling and innovative approaches to the study of modern Eu ro pe an Jewish history, thought, culture, and society. The series features scholarly works related to the Enlightenment, modern Judaism and the struggle for emancipation, the rise of nationalism and the spread of antisemitism, the Holocaust and its aftermath, as well as the contemporary Jewish experience. The series is published under the auspices of the Tauber Insti- tute for the Study of Eu ro pe an Jewry— established by a gift to Brandeis University from Dr. Laszlo N. Tauber— and is supported, in part, by the Tauber Foundation and the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www .upne .com Eugene M. Avrutin, Valerii Dymshits, Alexander Ivanov, Alexander Lvov, Harriet Murav, and Alla Sokolova, editors Photographing the Jewish Nation: Pictures from S. An- sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions Michael Dorland Cadaverland: Inventing a Pathology of Catastrophe for Holocaust Survival Walter Laqueur Best of Times, Worst of Times: Memoirs of a Po liti cal Education Berel Lang Philosophical Witnessing: The Holocaust as Presence David N. Myers Between Jew and Arab: The Lost Voice of Simon Rawidowicz Sara Bender The Jews of Białystock during World War II and the Holocaust Nili Scharf Gold Yehuda Amichai: The Making of Israel’s National Poet Hans Jonas Memoirs Itamar Rabinovich and Jehuda Reinharz, editors Israel in the Middle East: Documents and Readings on Society, Politics, and Foreign Relations, Pre- 1948 to the Present Christian Wiese The Life and Thought of Hans Jonas: Jewish Dimensions Eugene R. -

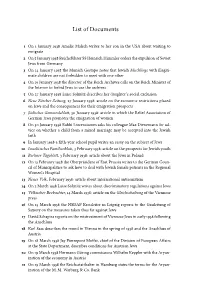

List of Documents

List of Documents 1 On 1 January 1938 Amalie Malsch writes to her son in the USA about waiting to emigrate 2 On 5 January 1938 Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler orders the expulsion of Soviet Jews from Germany 3 On 14 January 1938 the Munich Gestapo notes that Jewish Mischlinge with illegiti- mate children are not forbidden to meet with one other 4 On 19 January 1938 the director of the Reich Archives calls on the Reich Minister of theInteriortoforbidJewstousethearchives 5 On 27 January 1938 Luise Solmitz describes her daughter’s social exclusion 6 Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 27 January 1938: article on the economic restrictions placed on Jews and the consequences for their emigration prospects 7 Jüdisches Gemeindeblatt, 30 January 1938: article in which the Relief Association of German Jews promotes the emigration of women 8 On 30 January 1938 Rabbi Löwenstamm asks his colleague Max Dienemann for ad- vice on whether a child from a mixed marriage may be accepted into the Jewish faith 9 In January 1938 a fifth-year school pupil writes an essay on the subject of Jews 10 Israelitisches Familienblatt, 3 February 1938: article on the prospects for Jewish youth 11 Berliner Tageblatt, 3 February 1938: article about the Jews in Poland 12 On 13 February 1938 the Oberpräsident of East Prussia writes to the German Coun- cil of Municipalities to ask how to deal with Jewish female patients in the Regional Women’s Hospital 13 Neues Volk, February 1938: article about international antisemitism 14 On 2 March 1938 Luise Solmitz writes about discriminatory regulations -

German-Jewish Masculinities in the Third Reich, 1933-1945

Stolen Manhood? German-Jewish Masculinities in the Third Reich, 1933-1945 by Sebastian Huebel Bachelor of Arts, Thompson Rivers University, 2003 Master of Arts, University of Victoria, 2009 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2017 © Sebastian Huebel, 2017 Abstract When the Nazis came to power in Germany, they used various strategies to expel German Jews from social, cultural and economic life. My dissertation focuses on gendered forms of discrimination which had impacts on Jewish masculine identity. I am asking how Jewish men experienced these challenges and the undermining of their self-understandings as men in the Third Reich. How did Jewish men adhere to pre-established gender norms and practices such as the role of serving as the providers and protectors of their families? How did Jewish men maintain their sense of being patriotic German war veterans and members of the national community? And finally, how did Jewish men react to being exposed to the physical assaults and violence that was overwhelmingly directed against them in prewar Germany? These central questions form the basis of my study of Jewish masculinities in the Third Reich. I argue that Jewish men’s gender identities, intersecting with categories of ethnicity, race, class and age, underwent a profound process of marginalization that undermined their accustomed ways of performing masculinity; yet at the same time, in their attempts to sustain their conception of masculinity they maintained sufficient agency and developed coping strategies to prevent their full-scale emasculation. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Translated from my interview with Martin Beutler, Berlin, June 29, 1995, Shanghai Jewish Community Oral History Project, p. 545. This passage is published in my book, Shanghai-Geschichten: die jüdische Flucht nach China (Berlin: Hentrich und Hentrich, 2007), p. 241, which uses interviews in German to present the stories of 12 Shanghai refugees who later returned to Germany and Austria. 2. David Kranzler, Japanese, Nazis and Jews: The Jewish Refugee Community of Shanghai 1938–1945 (New York: Yeshiva University Press, 1976). See also James R. Ross , Escape to Shanghai: A Jewish Community in China (New York: Free Press, 1994). Films include Port of Last Resort (1999) by Paul Rosdy and Joan Grossman, and Shanghai Ghetto (2002) by Dana Janklowicz-Mann and Amir Mann. 3. Among the first were Evelyn Pike Rubin, Ghetto Shanghai (New York: Shengold Books, 1993); and I. Betty Grebenschikoff, Once My Name Was Sara (Ventnor, NJ: Original Seven Publishing Co., 1993). By combining the details of his own family’s stories with considerable research about the whole com- munity, the late Ernest Heppner’s Shanghai Refuge: A Memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1993) is the best of the memoirs. See the bibliography for this growing literature. 4. The most successful thus far is Michèle Kahn, Shanghai-la-juive (Paris: Flammarion, 1997). Vivian Jeanette Kaplan fictionalized her family’s expe- rience in Ten Green Bottles: The True Story of One Family’s Journey from War- torn Austria to the ghettos of Shanghai (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004). -

List of Documents

List of Documents 1 On 1 January 1938 Amalie Malsch writes to her son in the USA about waiting to emigrate 2 On 5 January 1938 Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler orders the expulsion of Soviet Jews from Germany 3 On 14 January 1938 the Munich Gestapo notes that Jewish Mischlinge with illegiti- mate children are not forbidden to meet with one other 4 On 19 January 1938 the director of the Reich Archives calls on the Reich Minister of theInteriortoforbidJewstousethearchives 5 On 27 January 1938 Luise Solmitz describes her daughter’s social exclusion 6 Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 27 January 1938: article on the economic restrictions placed on Jews and the consequences for their emigration prospects 7 Jüdisches Gemeindeblatt, 30 January 1938: article in which the Relief Association of German Jews promotes the emigration of women 8 On 30 January 1938 Rabbi Löwenstamm asks his colleague Max Dienemann for ad- vice on whether a child from a mixed marriage may be accepted into the Jewish faith 9 In January 1938 a fifth-year school pupil writes an essay on the subject of Jews 10 Israelitisches Familienblatt, 3 February 1938: article on the prospects for Jewish youth 11 Berliner Tageblatt, 3 February 1938: article about the Jews in Poland 12 On 13 February 1938 the Oberpräsident of East Prussia writes to the German Coun- cil of Municipalities to ask how to deal with Jewish female patients in the Regional Women’s Hospital 13 Neues Volk, February 1938: article about international antisemitism 14 On 2 March 1938 Luise Solmitz writes about discriminatory regulations -

Mirosława Lenarcik Jewish Charitable Foundations in Breslau

1 Mirosława Lenarcik Jewish charitable foundations in Breslau And when ye reap the harvest of your land, thou shalt not wholly reap the corners of thy field, neither shalt thou gather the gleanings of thy harvest. And thou shalt not glean thy vineyard, neither shalt thou gather every grape of thy vineyard; thou shalt leave them for the poor and stranger (Leviticus 19: 9f.) The obligation to help the poor and the needy and to give them gifts is stated many times in the Bible and was considered by the rabbis of all ages to be one of the cardinal commandments of Judaism. Everybody is obliged to give charity; even he who himself is dependent on charity should give to those less fortunate than himself. (Berenbaum and Skolnik 2007: 569575) It is believed that God is the owner of all things and that the owner of a field is only the temporary guardian of the land and the goods which it produces and that God requires the steward to give a portion of what he has been given to those in need. (Jewish Encyclopedia 19011906) These biblical commandments were implemented by the Jewish communities in a number of ways. The Hevra Kaddisha (burial society), which existed in almost all communities, regulated the allocation of graves and the rules for the erection of tombstones, and prepared the corpse in accordance with the traditions and laws for the reverential disposal of the dead. (Berenbaum and Skolnik 2007: vol. 9, 8182) Another traditional Jewish organisation, the BethaMidrash (“House of study”), was also established in Breslau as a result of philanthropic initiatives. -

Chapter One: the Historians

Relations between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans 1933-1945: A case study in the use of evidence by historians __________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History by Ruth L. Baker University of Canterbury 2009 _________________________________ Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures ................................................................................................................................. 2 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................ 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One..................................................................................................................................... 10 Historians: Their Sources and Use of Evidence............................................................................... 10 The Problem of Source Selection ................................................................................................ 15 The Problem with Use of Evidence............................................................................................. -

Course Syllabus

Course Syllabus Course Information Course Number/Section HIST 4344 Course Title The Holocaust and its Aftermath Term Spring 2017 Days & Times TTh: 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM Location ATC 2.602 Professor Contact Information Professor Zsuzsanna Ozsváth Office Phone 972-883-2756 Email Address Ozsvá[email protected] Office Location JO 4.800 Office Hours By Appointment Professor Contact Information Professor Nils Roemer Office Phone 972-883-2769 Email Address [email protected] Office Location JO 4.800 Office Hours By Appointment Course Pre-requisites, Co-requisites, and/or Other Restrictions No prior background is assumed or required. Course Description Taking an interdisciplinary approach, this course explores the Holocaust and its aftermath. It challenges our fundamental assumptions and values, and it raises questions of great urgency: “What was the background of the Holocaust?” How was it possible for a state to systematize, mechanize, and socially organize this assault on the Jewish people?” And “How could the Nazis in a few years eliminate the foundations of Western civilization?” Our course will search for answers to these questions and investigate many others. In addition, it will explore the ways in which the Holocaust is often denied as well as those in which it is commemorated in the Nuremberg and Eichmann trials, in survivor testimonies, in Holocaust literature, art, memorials, museums, and films. The course is taught by two professors, and its instructional format will be lecture with substantial discussion. Required Textbooks and Materials Doris Bergen, War and Genocide: A Concise History of the Holocaust, 3rd ed. (2016. ISBN 978-1- 4422-4228-9 Jerzy Kosinski, The Painted Bird. -

List of Documents

List of Documents Part 1: German Reich 1 The writer Walter Tausk records his experiences in Breslau on 1 September 1939, the day the war broke out 2 On 1 September 1939 Emilie Braach from Frankfurt writes to her émigré daughter in Britain, describing how everyday life is changing with the start of war 3 On 2 and 3 September 1939 the historian Arnold Berney, an émigré in Jerusalem, records his gloomy prognoses on the outbreak of war 4 On 5 September 1939 the State Commissioner for Private Industry to the Reichsstatt- halter of Vienna proposes that the Viennese Jews be confined to forced labour camps 5 On 6 September 1939 the Gestapo Central Office instructs its regional branches to prevent acts of violence against Jews, and announces pending anti-Jewish measures 6 On 7 September 1939 Reinhard Heydrich orders the arrest of all male Polish Jews over the age of 16 in the Reich 7 On 8 September 1939 Walter Grundmann reports to Reich Minister of Church Af- fairs Hanns Kerrl on the work of the Institute for the Study and Elimination of Jew- ish Influence on German Church Life 8 On 10 September 1939 Willy Cohn writes in his diary about the increasingly anti- semitic atmosphere in Breslau 9 On 11 September 1939 the NSDAP Kreisleitung for Kitzingen-Gerolzhofen reports on attacks on Jews and calls for the incarceration of all Jews in a concentration camp 10 On the basis of a denunciation, on 13 September 1939 the Munich Gestapo accuses Felizi Weill of inciting hatred against the German state leadership 11 Aufbau, 15 September 1939: article on the -

98 • 2020 98 • 2020

98 • 2020 FASC. 3: LANGUES ET LITTÉRATURES MODERNES AFL. 3: MODERNE TAAL- EN LETTERKUNDE 98 • 2020 SOCIÉTÉ POUR LE PROGRÈS DES ÉTUDES PHILOLOGIQUES ET HISTORIQUES fondée en 1874 Président: Jean-Marie DUVOSQUEL, 44 (boîte 1), avenue Adolphe Buyl, 1050 Bruxelles. Secrétaire général: Denis MORSA, 29/3, avenue Émile Vandervelde, 1200 Bruxelles. Trésorier: David GUILARDIAN, 326 (boîte 5), Avenue Brugmann, 1180 Bruxelles. L’organe de la Société est la Revue belge de Philologie et d’Histoire, recueil trimestriel dont le tome I est paru en 1922. Het Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Filologie en Geschiedenis wordt uitgegeven door de Société. Het Tijdschrift werd gesticht in 1922. REVUE BELGE DE PHILOLOGIE ET D’HISTOIRE BELGISCH TIJDSCHRIFT VOOR FILOLOGIE EN GESCHIEDENIS Website : http://www.rbph-btfg.be Directeur: Michèle GALAND. Comité directeur – Bestuurcomité: il rassemble les membres du Bureau de la Société (voir ci-dessus) et du Comité de Rédaction de la Revue (voir en p. 3 de couverture) – Het Bestuurcomité bestaat uit de leden van het Bureau van de “Société” (zie hierboven) en van de Redactieraad van het Tijdschrift (zie blz. 3 van de omslag). Membres honoraires – Ereleden: M. BOUSSART (ULB), J.-M. D’HEUR (ULg), J. DUYTSCHAEVER (UIA), P. F ONTAINE (UCL), L. LESUISSE (ISL), Chr. LOIR (ULB), R. VAN EENOO (UGent), J.-P. VAN NOPPEN (ULB). Comité de lecture international – Internationaal leescomité: Jan ART (Gent); Philip BENNETT (Edinburgh); Marc BOONE (Gent); Laurence BOUDART (Bruxelles, Archives et Musée de la Littérature); Véronique BRAGARD (Louvain-la-Neuve);