SIX HUNDRED YEARS of CRAFT RITUAL by Harry Carr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature A Brief Study Ritgerð til MA-prófs í íslenskum miðaldafræðum Li Tang Kt.: 270988-5049 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius September 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my supervisor, Torfi H. Tulinius for his confidence and counsels which have greatly encouraged my writing of this paper. Because of this confidence, I have been able to explore a domain almost unstudied which attracts me the most. Thanks to his counsels (such as his advice on the “Blóð-Egill” Episode in Knýtlinga saga and the reading of important references), my work has been able to find its way through the different numbers. My thanks also go to Haraldur Bernharðsson whose courses on Old Icelandic have been helpful to the translations in this paper and have become an unforgettable memory for me. I‟m indebted to Moritz as well for our interesting discussion about the translation of some paragraphs, and to Capucine and Luis for their meticulous reading. Any fault, however, is my own. Abstract It is generally agreed that some numbers such as three and nine which appear frequently in the two Eddas hold special significances in Norse mythology. Furthermore, numbers appearing in sagas not only denote factual quantity, but also stand for specific symbolic meanings. This tradition of number symbolism could be traced to Pythagorean thought and to St. Augustine‟s writings. But the result in Old Norse literature is its own system influenced both by Nordic beliefs and Christianity. This double influence complicates the intertextuality in the light of which the symbolic meanings of numbers should be interpreted. -

BEHIND the MUSIC Featuring Nicola Benedetti Larkinsurance.Co.Uk

ISSUE 5 BEHIND THE MUSIC Featuring Nicola Benedetti larkinsurance.co.uk What’s Inside Cover Story 12-15 4-5 Nicola Benedetti at 30 I had to be tough She has no wish for lavish gifts on her 30th birthday but Lyric baritone Sir Thomas Allen has natural Nicola Benedetti expresses her desire to fathom a way to talent and shares his craft by encouraging formalise her education work young opera hopefuls 26-29 22-25 Land of legends It was serendipity The Gower Festival goes from strength to strength, thanks Annette Isserlis put her heart and soul into to a music-loving team led by Artistic Director Gordon arranging the posthumous birthday concert in Back who has been attracting top musicians to the idyllic honour of Francis Baines – and she planned it peninsula in south-west Wales in her personal woodland Welcome t is fascinating to discover what goes on behind the scenes in the world of top-class music and inside this issue of LARKmusic I hope you will enjoy reading the exclusive features which capture our Iinterviewees’ passion and incredible drive for perfection. The Lark team has been enjoying some wonderful music, attending events from the Francis Baines’ centenary concert to recitals at the Royal College of Music, the Suffolk schools’ Celebration at Snape Maltings and this summer’s Gower Festival – meeting clients and making new friends along the way. Read on for the full stories! Back in the office, it’s been busy with a focus on improving our insurance products and online service so I am pleased to introduce our new Public Liability Cover, as well as highlighting our new quote and buy portal which will make buying insurance cover online even more convenient. -

Mythology and Esoteric Truths Our Food from God the Three Degrees of Discipleship Prayer and the New Panacea

“A Sane Mind, A Soft Heart, A Sound Body” November/December 2002—$5.00 MYTHOLOGY AND ESOTERIC TRUTHS OUR FOOD FROM GOD THE THREE DEGREES OF DISCIPLESHIP PRAYER AND THE NEW PANACEA A CHRISTIAN ESOTERIC MAGAZINE GLORIA IN PROFUNDIS There has fallen on earth for a token For in dread of such falling and failing A god too great for the sky. The Fallen Angels fell He has burst out of all things and broken Inverted in insolence, scaling The bounds of eternity: The hanging mountain of hell: Into time and the terminal land But unmeasured of plummet and rod He has strayed like a thief or a lover, Too deep for their sight to scan, For the wine of the world brims over, Outrushing the fall of man Its splendor is spilt on the sand. Is the height of the fall of God. Who is proud when the heavens are humble, Glory to God in the Lowest Who mounts if the mountains fall, The spout of the stars in spate— If the fixed suns topple and tumble Where the thunderbolt thinks to be slowest And a deluge of love drown all— And the lightning fears to be late: Who rears up his head for a crown, As men dive for a sunken gem Who holds up his will for a warrant, Pursuing, we hunt and hound it, Who strives with the starry torrent The fallen star that has found it When all that is good goes down? In the cavern of Bethlehem. Front cover: Adoration of the Child, Filippo Lippi, Staatliche Museen, Berlin. -

Moon-Earth-Sun: the Oldest Three-Body Problem

Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem Martin C. Gutzwiller IBM Research Center, Yorktown Heights, New York 10598 The daily motion of the Moon through the sky has many unusual features that a careful observer can discover without the help of instruments. The three different frequencies for the three degrees of freedom have been known very accurately for 3000 years, and the geometric explanation of the Greek astronomers was basically correct. Whereas Kepler’s laws are sufficient for describing the motion of the planets around the Sun, even the most obvious facts about the lunar motion cannot be understood without the gravitational attraction of both the Earth and the Sun. Newton discussed this problem at great length, and with mixed success; it was the only testing ground for his Universal Gravitation. This background for today’s many-body theory is discussed in some detail because all the guiding principles for our understanding can be traced to the earliest developments of astronomy. They are the oldest results of scientific inquiry, and they were the first ones to be confirmed by the great physicist-mathematicians of the 18th century. By a variety of methods, Laplace was able to claim complete agreement of celestial mechanics with the astronomical observations. Lagrange initiated a new trend wherein the mathematical problems of mechanics could all be solved by the same uniform process; canonical transformations eventually won the field. They were used for the first time on a large scale by Delaunay to find the ultimate solution of the lunar problem by perturbing the solution of the two-body Earth-Moon problem. -

Preowned 1970S Sheet Music

Preowned 1970s Sheet Music. PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE Offers Not priced – Offers please. ex No marks or deteriation Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside. Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered.. Year Year of print. Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover STAMP OUT FORGERIES. Warning: It has come to our attention that there are sheet music forgeries in circulation. In particular, items showing Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard, The Beatles and Gene Vincent have recently been discovered to be bootleg reprints. Although we take every reasonable precaution to ensure that the items we have for sale are genuine and from the period described, we urge buyers to verify purchases from us and bring to our attention any item discovered to be fake or falsely described. The public can thus be warned and the buyer recompensed. Your cooperation is appreciated. 1970s Title Writer and composer condition Photo year Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a © 1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and small Johnny Pearson good sheep grazing 1977 All I ever need is you J.Holiday/E.Reeves ex Sonny & Cher 1972 All I think about is you Harry Nilsson ex Harry Nilsson 1977 Amanda Brian Hall ex Stuart Gillies 1973 Amarillo (is this the way to) N.Sedaka/H.Greenfield ex Tony Christie 1971 Amazing grace Trad. -

Symbolism Three Degrees

SYMBOLISM OF THE THREE DEGREES A SERIES OF LECTURES BY BROTHER OLIVER DAY STREET GUNTERSVILLE, ALABAMA Cover art: "Light & Truth" The Brotherhood Art Publishing Co., Boston, 1905. Charts of this design were started by Jeremy Cross, a teacher of the Masonic ritual, who, during his lifetime, was extensively known, and for some time very popular. He was born June 27, 1783, at Haverhill, New Hampshire, and died ate th same place in I86I. Cross was admitted into the Masonic Order in 1808, and soon afterward became a pupil of Thomas Smith Webb, whose modifications of the Preston lectures and of the advanced Degrees were generally accepted by the Freemasons of the United States. Cross, having acquired a competent knowledge of Webb's system, began to travel and disseminate it throughout the country. In 1819 he published The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor, in which he borrowed liberally from the previous work of Webb. Photograph by Kenneth Olson, Spirit Lake Iowa from a chart hanging in the James & Cynthia Hayes Masonic Gallery housed in the Sioux City Scottish Rite, 801 Douglas Street, Sioux City IA. SYMBOLISM OF THE THREE DEGREES A SERIES OF LECTURES BY BROTHER OLIVER DAY STREET GUNTERSVILLE, ALABAMA REPRINTED FROM THE BUILDER THE OFFICAL JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MASONIC RESEARCH SOCIETY ANAMOSA, IOWA I N D E X PART I THE ENTERED APPRENTICE DEGREE .............. Page 1 PART II THE FELLOW CRAFT DEGREE .......................... Page 17 PART III THE MASTER MASON DEGREE ........................ Page 29 SYMBOLISM OF THE THREE DEGREES PART I THE ENTERED APPRENTICE DEGREE IT is first necessary that we should understand the scope of my subject. -

Singles 1970 to 1983

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS PHILIPS–PHONOGRAM 7”, EP’s and 12” singles 1970 to 1983 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 PHILIPS-PHONOGRAM, 1970-83 2001 POLYDOR, ROCKY ROAD, JET 2001 007 SYMPATHY / MOONSHINE MARY STEVE ROWLAND & FAMILY DOGG 5.70 2001 072 SPILL THE WINE / MAGIC MOUNTAIN ERIC BURDON & WAR 8.70 2001 073 BACK HOME / THIS IS THE TIME OF THE YEAR GOLDEN EARRING 10.70 2001 096 AFTER MIDNIGHT / EASY NOW ERIC CLAPTON 10.70 2001 112 CAROLINA IN MY MIND / IF I LIVE CRYSTAL MANSION 11.70 2001 120 MAMA / A MOTHER’S TEARS HEINTJE 3.71 2001 122 HEAVY MAKES YOU HAPPY / GIVE ‘EM A HAND BOBBY BLOOM 1.71 2001 127 I DIG EVERYTHING ABOUT YOU / LOVE HAS GOT A HOLD ON ME THE MOB 1.71 2001 134 HOUSE OF THE KING / BLACK BEAUTY FOCUS 3.71 2001 135 HOLY, HOLY LIFE / JESSICA GOLDEN EARING 4.71 2001 140 MAKE ME HAPPY / THIS THING I’VE GOTTEN INTO BOBBY BLOOM 4.71 2001 163 SOUL POWER (PT.1) / (PTS.2 & 3) JAMES BROWN 4.71 2001 164 MIXED UP GUY / LOVED YOU DARLIN’ FROM THE VERY START JOEY SCARBURY 3.71 2001 172 LAYLA / I AM YOURS DEREK AND THE DOMINOS 7.72 2001 203 HOT PANTS (PT.1) / (PT.2) JAMES BROWN 10.71 2001 206 MONEY / GIVE IT TO ME THE MOB 7.71 2001 215 BLOSSOM LADY / IS THIS A DREAM SHOCKING BLUE 10.71 2001 223 MAKE IT FUNKY (PART 1) / (PART 2) JAMES BROWN 11.71 2001 233 I’VE GOT YOU ON MY MIND / GIVE ME YOUR LOVE CAROLYN DAYE LTD. -

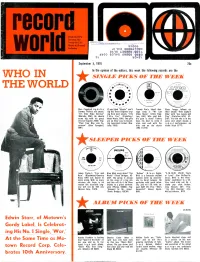

Who in Single Picks of the Week the World

record Dedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Musk & Recoi 9P006 Industry 4 r 1r3 aQOAAA110H world 0A19 13SNQS Ox l L dtiO3 S31VS ONROS 91!!O O9 a0-zi September 5, 1910 15c In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the WHO IN SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK THE WORLD ., Glen Campbell updates If you liked "Maybe" you'll Tommy Roe's latest mes- Blues Image follows up Conway Twitty's old smash, dig the Three Degrees sing- sage song is "We Can their smash "Ride Captain "It's Only Make Believe" ing their next smash, "I Do Make Music" (Little Fugi- Ride" with "Gas Lamps and (Marielle, BMI). He should Take You." (Planetary/ tive, BMI). Who said bub- Clay" (Portofino/ATM, AS - score big with his great Make Music, BMI). The girls ble gum is dead? Tommy CAP). The new one is in the version (Capitol 2905(. Flip: are on their way to becom- does his best to keep it same vein which means a "Pave Your Way into To- ing consistent sellers (Rou- alive and well with the repeat performance, no morrow" (Glen Campbell, lette 7088(. kids and on the charts doubt (Atco 6777). BMI). (ABC 11273(. SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK PH! 1f?p.S P.M JAMES IAYEtR FIRE AND RAIN James Taylor's "Fire and Blue Mink sings about "Our "Rubies" (Green Apple, "5.10.15-20 (25-30 Years Rain" (Blackwood/Country World" (Three Bridges, AS - BMI) is a fantastic rhythm of Love)" (Van McCoy/In- Road, BMI) was bound to CAP). -

Jukebox Decades – 100 Hits Ultimate Soul

JUKEBOX DECADES – 100 HITS ULTIMATE SOUL Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Ain’t No Sunshine Bill Withers 01 Be My Baby The Ronettes 02 How ‘Bout Us Champaign 02 Captain Of Your Ship Reparata 03 Sexual Healing Marvin Gaye 03 Band Of Gold Freda Payne 04 Me & Mrs. Jones Billy Paul 04 Midnight Train To Georgia Gladys Knight 05 If You Don’t Know Me Harold Melvin 05 Piece of My Heart Erma Franklin 06 Turn Off The Lights Teddy Pendergrass 06 Woman In Love The Three Degrees 07 A Little Bit Of Something Little Richard 07 I Need Your Love So Desperately Peaches 08 Tears On My Pillow Johnny Nash 08 I’ll Never Love This Way Again D Warwick 09 Cause You’re Mine Vibrations 09 Do What You Gotta Do Nina Simone 10 So Amazing Luther Vandross 10 Mockingbird Aretha Franklin 11 You’re More Than A Number The Drifters 11 That’s What Friends Are For D Williams 12 Hold Back The Night The Tramps 12 All My Lovin’ Cheryl Lynn 13 Let Love Come Between Us James 13 From His Woman To You Barbara Mason 14 After The Love Has Gone Earth Wind & Fire 14 Personally Jackie Moore 15 Mind Blowing Decisions Heatwave 15 Every Night Phoebe Snow 16 Brandy The O’ Jays 16 Saturday Love Cherrelle 17 Just Be Good To Me The S.O.S Band 17 I Need You Pointer Sisters 18 Ready Or Not Here I The Delfonics 18 Are You Lonely For Me Freddie Scott 19 Home Is Where The Heart Is B Womack 19 People The Tymes 20 Birth The Peddlers 20 Don’t Walk Away General Johnson Disc Three - Title Artist Disc Four - Title Artist 01 Till Tomorrow Marvin Gaye 01 Lean On Me Bill Withers 02 Here -

Masonic Token: January 15, 1890

• NYf .‘'p^SNnyg MA SONIC TOKEN. WHEREBY ONE BROTHER MAY KNOW ANOTHER. VOLUME 3. PORTLAND, JAN. 15, 1890. NO. 11. Euclid, 194, Madison. Hiram L Harris, A Underwood, m ; Wm E Stevens, sw; Published quarterly by Stephen Berry, tn; Marcellus S Perkins, sw ; Charles O Charles R Keopka, jw ; Wm Parker, sec. No. 37 Plum Street, Portland. Huntoon, jw ; Charles A Wilber, see. Pine Tree, 172, Mattawamkeag. Wm T Archon, 139, East Dixmont. Amos B T Mincher, m; James H Chadbourne. sw; Twelve cts. per year in advance. Ugg** Postage prepaid. Chadbourne, m; John F Tasker, sw; Jere Charles P Van Vleck, jw ; Geo W Smith, miah Smith, jw ; Benj. F. Porter, sec. sec. Advertisements $4.00 per inch, or $3.00 for Sebastieook, 146, Clinton. John P Bil- Preble, 143, Sanford. Wm Batchelder, half an inch for one year. lings, m ; B G True, sw ; D W Stewart, jw ; m ; Calvert Longbottom, sw ; Chas F Moul R W Gerald, sec. No advertisement received unless the advertiser, ton, jw ; Rev S H Emery, sec. or some member of the firm, is a Freemason in Cumberland, 12, New Gloucester. Wm M Mosaic, 5'2, Foxcroft. John C Cross, m ; good standing. Dow, m; Parker W Sawyer, sw; Thomas Wallace M Thayer, sw; Warren L Stod G Galvin, jw ; Geo H Goding, So. Auburn, dard, jw ; James T Roberts, sec. sec. [For the Masonic Token.'] Temple, 86, Saccarappa. ^/ephen II Bethlehem, 35, Augusta. Ethel H Jones, Skillings, m; Frank II Allen, sw; T S THE WANDER-YEAR. m; W S Choate, sw ; Edwin H Gay, jw ; Burns, jw ; Oliver A Cobb, sec. -

From the East

From The East “And I Vouch For Him” Did you ever find yourself standing in front of a mirror saying, ‘You know, I still look pretty good’, all the while not admitting that you’re at least 20-25 pounds heavier (if not more) than when you really did look good, your hair is thinning (if not entirely gone, or at least a totally different color), except that which is now growing out of your ears and nose (what’s with that?!?), and gravity has long since won the battle where your once finely chiseled pecs are now ‘man boobs’ (not to mention your gluteus maximus)? This is typical of what we all go through and reveals the fact that our self-image is usually much different than the way others tend to perceive us or how we tend to perceive others. We recently had a situation in our Lodge where a good Mason asked some of our brothers to sign off on a new petitioner. This brother is well liked, and a good Mason and the petitioner was a member of his church. Four other men signed off on him simply because they were asked to do so by a good Mason they all knew and respected. The Investigation Committee asked those four brethren, ‘Do you know this man well enough that you would trust him to be alone with your 16 year old daughter?’, and of course the answer was no. Thus, the Investigating Committee rejected the petitioner’s application on the grounds that none of the brothers who signed his application knew him well enough to vouch for him, and the application was never submitted to the Lodge for a vote. -

The Three Degrees the Three Degrees Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Three Degrees The Three Degrees mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: The Three Degrees Country: UK Released: 1981 Style: Soul MP3 version RAR size: 1208 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1179 mb WMA version RAR size: 1144 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 116 Other Formats: AA VQF ADX VOC RA AU TTA Tracklist 1 Tie U Up 6:13 2 Make It Easy On Yourself 4:44 3 After The Night Is Over 5:14 4 Are You That Kind Of Guy 5:39 5 When Will I See You Again 2:51 6 Midnight Train 4:03 7 Dirty Ol' Man 4:18 8 Nigai Namida 3:47 9 T.S.O.P. (The Sound Of Philadelphia) 3:32 10 I'm Doin' Fine Now 3:34 11 I'm Going To Miss You 3:06 12 I'll Be Around 3:26 13 Do Right Woman, Do Right Man 3:17 14 Let's Get It On 4:34 Credits Design – CPI Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 033107 107629 Rights Society: MCPS Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Three Let's Get It On (CD, Tring International SJP015 SJP015 UK 1993 Degrees Comp, RM) PLC The Three Let's Get It On (CD, Tring International ME 103 ME 103 Japan 1993 Degrees Comp, RM) PLC Related Music albums to The Three Degrees by The Three Degrees Gat Decor vs. Degrees Of Motion, Minnie Riperton - Degrees Of Passion / Loving You The Three Degrees - A Collection Of Their 20 Greatest Hits Kylie Minogue, Dannii Minogue - 100 Degrees (It's Still Disco To Me) The Three Degrees - Free Ride / Loving Cup Three Degrees, The - The Three Degrees The Three Degrees - Year Of Decision 2 Degrees And The Madd Squad - Guess Who? The Three Degrees - When Will I See You Again / Year Of Decision Three Degrees, The - New Dimensions The Three Degrees - When Will I See You Again The Three Degrees & MFSB Orchestra - Take Good Care Of Yourself Jimmy Witherspoon - Failing By Degrees / New-Orleans Woman.