Guide to Cuban Law and Legal Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1 PETER C. BJARKMAN www.bjarkman.com Cuban Baseball Historian Author and Internet Journalist Post Office Box 2199 West Lafayette, IN 47996-2199 USA IPhone Cellular 1.765.491.8351 Email [email protected] Business phone 1.765.449.4221 Appeared in “No Reservations Cuba” (Travel Channel, first aired July 11, 2011) with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain Featured in WALL STREET JOURNAL (11-09-2010) front page story “This Yanqui is Welcome in Cuba’s Locker Room” PERSONAL/BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Born: May 19, 1941 (72 years old), Hartford, Connecticut USA Terminal Degree: Ph.D. (University of Florida, 1976, Linguistics) Graduate Degrees: M.A. (Trinity College, 1972, English); M.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1970, Education) Undergraduate Degree: B.S.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1963, Education) Languages: English and Spanish (Bilingual), some basic Italian, study of Japanese Extensive International Travel: Cuba (more than 40 visits), Croatia /Yugoslavia (20-plus visits), Netherlands, Italy, Panama, Spain, Austria, Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, Canada, Japan. Married: Ronnie B. Wilbur, Professor of Linguistics, Purdue University (1985) BIBLIOGRAPHY March 2014 MAJOR WRITING AWARDS 2008 Winner – SABR Latino Committee Eduardo Valero Memorial Award (for “Best Article of 2008” in La Prensa, newsletter of the SABR Latino Baseball Research Committee) 2007 Recipient – Robert Peterson Recognition Award by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, for advancing public awareness -

Fuller and the Folk: the Inner Morality of Law Revisited

Forthcoming in T. Lombrozo, J. Knobe, & S. Nichols (Eds.), Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy, Volume 3. Oxford: UK, Oxford University Press. Fuller and the Folk: The Inner Morality of Law Revisited Raff Donelson Ivar R. Hannikainen LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PONTIFICAL CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY [email protected] OF RIO DE JANEIRO [email protected] The philosophy of law, or jurisprudence, is an concept has—this empirical debate would area of study wherein experimental methods benefit from empirical research. In are largely absent but sorely needed. It is particular, we might seek out folk puzzling that the experimental turn has been psychological evidence, predicated on the slow in coming to jurisprudence, as the field positive impact such evidence has had in other straddles two disciplines where empirical domains of philosophy. evidence is increasingly common. On one The foregoing may not be convincing. flank, empirical studies have long been Traditional legal philosophers who do not use popular among non-philosophers in law empirical methods will need to hear more to departments; on the other, experimental appreciate why strange, new techniques methods now abound in many areas of might be appropriate. Experimental philosophy. philosophers who have yet to consider While it is difficult to understand why few jurisprudence will need to hear more about have adopted an experimental approach to the subfield and its issues to understand how jurisprudence, it is clear why experimental they might contribute. We hope to address jurisprudence should be on the agenda: legal such philosophers and others, but not with a philosophers routinely ask questions that are purely metaphilosophical tract. -

INSIDE the U.S

Vol. XII, No. 5 www.cubatradenews.com May 2010 Ag debate shifts to privatizing distribution radually moving the focus of reform Selling debate from state decentralization to potatoes part-privatization,G private farmers at a three- in Trinidad, day congress of the National Association of Cuba Small Farmers (ANAP) blamed the state for bottlenecks in food production and distribution in Cuba, and — while not using the p-word — proposed more privatization of distribution. Photo: Rosino, Wikimedia Photo: Rosino, In a 37-point resolution, the organization representing some 362,000 private farmers supports the expansion of suburban agriculture with direct distribution to Also see: city outlets, and suggests allowing the Opinion direct sale of cattle to slaughterhouses page 3 by cooperatives, direct farm sales to the tourist sector, and that the state promote and support farm-based micro-processing plants for local crops, whose products should be freely sold on markets. Private farmers — ranging from small landowners leasing state land to cooperative Cont’d on page 5 U.S. grants Cuba travel license to Houston-based oil group he International Association of Drilling Contractors Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control rejected IADC’s received a travel license from the U.S. Department of first license application in December. Al Fox and the group TreasuryT May 19, allowing the Houston-based group to send appealed and reapplied in March; OFAC granted the license a delegation to Cuba within three months, Tampa lobbyist and Continued on next page businessman Al Fox told Cuba Trade & Investment News. This marks the first time a U.S. -

Trading with the Enemy: Opening the Door to U.S. Investment in Cuba

ARTICLES TRADING WITH THE ENEMY: OPENING THE DOOR TO U.S. INVESTMENT IN CUBA KEVIN J. FANDL* ABSTRACT U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba have been in place for nearly seven deca- des. The stated intent of those sanctionsÐto restore democracy and freedom to CubaÐis still used as a justi®cation for maintaining harsh restrictions, despite the fact that the Castro regime remains in power with widespread Cuban public support. Starving the Cuban people of economic opportunities under the shadow of sanctions has signi®cantly limited entrepreneurship and economic development on the island, despite a highly educated and motivated popula- tion. The would-be political reformers and leaders on the island emigrate, thanks to generous U.S. immigration policies toward Cubans, leaving behind the Castro regime and its ardent supporters. Real change on the island will come only if the United States allows Cuba to restart its economic engine and reengage with global markets. Though not a guarantee of political reform, eco- nomic development is correlated with demand for political change, giving the economic development approach more potential than failed economic sanctions. In this short paper, I argue that Cuba has survived in spite of the U.S. eco- nomic embargo and that dismantling the embargo in favor of open trade poli- cies would improve the likelihood of Cuba becoming a market-friendly communist country like China. I present the avenues available today for trade with Cuba under the shadow of the economic embargo, and I argue that real po- litical change will require a leap of faith by the United States through removal of the embargo and support for Cuba's economic development. -

Constitution of Cuba

Constitution of Cuba Preamble WE, CUBAN CITIZENS, heirs and continuators of the creative work and the traditions of combativity, firmness, heroism and sacrifice fostered by our ancestors; by the Indians who preferred extermination to submission; by the slaves who rebelled against their masters; by those who awoke the national consciousness and the ardent Cuban desire for an independent homeland and liberty; by the patriots who in 1868 launched the wars of independence against Spanish colonialism and those who in the last drive of 1895 brought them to the victory of 1898, victory usurped by the military intervention and occupation of Yankee imperialism; by the workers, peasants, students, and intellectuals who struggled for over fifty years against imperialist domination, political corruption, the absence of people’s rights and liberties, unemployment and exploitation by capitalists and landowners; by those who promoted, joined and developed the first organization of workers and peasants, spread socialist ideas and founded the first Marxist and Marxist-Leninist movements; by the members of the vanguard of the generation of the centenary of the birth of Martí who, imbued with his teachings, led us to the people’s revolutionary victory of January; by those who defended the Revolution at the cost of their lives, thus contributing to its definitive consolidation; by those who, en masse, accomplished heroic internationalist missions; GUIDED by the ideology of José Martí, and the sociopolitical ideas of Marx, Engels, and Lenin; SUPPORTED by -

New Castro Same Cuba

New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-562-8 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2009 1-56432-562-8 New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era I. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 7 II. Illustrative Cases ......................................................................................................................... 11 Ramón Velásquez -

PEPA FLORES GOYA DE HONOR 2020 PEPA FLORES Goya De Honor a | Goya De Honor 2020 4 Pepa Flores Especial Nominados Premios Goya

ACADEMIA.La revista del cine español PEPA FLORES GOYA DE HONOR 2020 PEPA FLORES GOYA DE HONOR A | Goya de Honor 2020 4_ Pepa Flores Especial Nominados Premios Goya 19 MEJOR DIRECCIÓN Pedro Almodóvar: “Siempre me he visto fabulando” | Aitor Arregi, Jon Garaño y Jose Mari Goenaga: “Solo reivindica el olvido quien está incómodo con el pasado” | Oliver Laxe: “Tenemos que ser menos autores y más servidores” | Alejandro Amenábar: “Es bueno dejarse impregnar por el de enfrente” 34 MEJOR DIRECCIÓN NOVEL Salvador Simó, Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia, Belén Funes y Aritz Moreno 38 MEJOR GUIÓN ADAPTADO ‘Nuestro viaje con Luis Buñuel al laberinto de las tortugas’, por Eligio Montero y Salvador Simó | ‘Mancharse las manos’, por Pablo Remón y Daniel Remón | ‘Decir adiós’, por Isabel Peña y Rodrigo Sorogoyen ‘Lasaña infinita’, por Javier Gullón 42 MEJOR MÚSICA ORIGINAL Guerra y tortugas 44 INTÉRPRETES Los cineastas escriben sobre sus actores y actrices nominados Antonio Banderas, Penélope Cruz, Asier Exteandia, Leonardo Sbaraglia, Julieta Serrano, por Pedro Almodóvar | Karra Elejarde, Eduard Fernández, Nathalie Poza Santi Prego y Ainhora Santamaría por Alejandro Amenábar | Pilar Gómez, Natalia de Molina y Mona Martínez, por Paco Cabezas | Antonio de la Torre, Belén Cuesta y Vicente Vergara, por Aitor Arregi, Jon Garaño y Jose Mari Goenaga | Luis Tosar y Enric Auquer, por Paco Plaza | Greta Fernández, por Belén Funes | Marta Nieto, por Rodrigo Sorogoyen | Luis Callejo, por Benito Zambrano | Nacho Sánchez, por Daniel Sánchez Arévalo | Benedicta Sánchez, por Oliver Laxe | Carmen Arrufat, por Lucía Alemany 66 MEJOR MONTAJE. ‘El veneno del cine’, por Teresa Font | ‘La duración exacta’, por Laurent Dufreche y Raúl López | ‘Más allá de las palabras’, por Alberto del Campo | ‘Medir el tiempo’, por Carolina Martínez Urbina 70 MEJOR PELÍCULA DE ANIMACIÓN. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

Consejo De Redacción De Convivencia: Obra De Portada: Director: Dagoberto Valdés Hernández “¡A La Mesa!” 2014 Karina Gálvez Chiú Mixta (Acrílico) Lienzo

Consejo de Redacción de Convivencia: Obra de Portada: Director: Dagoberto Valdés Hernández “¡A la mesa!” 2014 Karina Gálvez Chiú Mixta (Acrílico) Lienzo. 75 x 109 cm Maikel Iglesias Rodríguez Serie: “Dichoso el hombre que soporta la prueba...” Rosalia Viñas Lazo Santiago 1.12. No. 37 Livia Gálvez Chiú Obra: Alan Manuel González Henry Constantín Ferreiro Yoandy Izquierdo Toledo Contraportada: Serie “Postales del Hoyo del Guamá” (7) Diseño y Administración Web: Javier Valdés Delgado Foto: Maikel Iglesias Rodríguez Equipo de realización: Colaboradores permanentes: Composición computarizada: Yoani Sánchez Rosalia Viñas Lazo Reinaldo Escobar Casas Correcciones: Olga Lidia López Lazo Livia Gálvez Chiú Virgilio Toledo López Yoandy Izquierdo Toledo Asistencia Técnica: Contáctenos en: Arian Domínguez Bernal www.convivenciacuba.es Secretaría de Redacción: www.convivenciacuba.es/intramuros Hortensia Cires Díaz [email protected] Luis Cáceres Piñero Web master: [email protected] Marianela Gómez Luege Relaciones Públicas y Mensajería: Margarita Gálvez Martínez Juan Carlos Fernández Hernández Suscripciones por e-mail: Javier Valdés Delgado ([email protected]) Diseño digital para correo electrónico (HTML): Maikel Iglesias Rodríguez EN ESTE NÚMERO EDITORIAL Restablecer las relaciones democráticas entre el pueblo y el gobierno cubanos..................................5 CULTURA: ARTE, LITERATURA... Galería Curriculum vitae de Alan Manuel González...........................................................................................8 -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making

Indiana Law Journal Volume 68 Issue 2 Article 3 Spring 1993 The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making Scott C. Idleman Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Idleman, Scott C. (1993) "The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 68 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol68/iss2/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making SCOTT C. IDLEMAN* [U]nless people believe in the law, unless they attach a universal and ultimate meaning to it, unless they see it and judge it in terms of a transcendent truth, nothing will happen. The law will not work-it will be dead.' INTRODUCTION It is virtually axiomatic today that judges should not advert to religious values when deciding cases,2 unless those cases explicitly involve religion.' In part because of historical and constitutional concerns and in * J.DJM.P.A. Candidate, 1993, Indiana University School of Law at Bloomington; B.S., 1989, Cornell University. 1. HAROLD J. BERMAN, THE INTERACTION OF LAW AND RELIGION 74 (1974). 2. See, e.g., KENT GREENAWALT, RELIGIOUS CONVICTIONS AND POLITICAL CHOICE 239 (1988); Stephen L. -

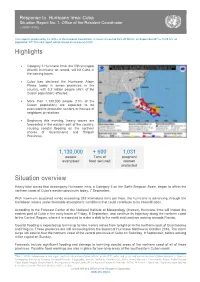

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida.