Badilu Assefa Ayana Advisor: Fikadu Adugna (Phd)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music

China Perspectives 2020-2 | 2020 Sinophone Musical Worlds (2): The Politics of Chineseness Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music Nathanel Amar Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/10063 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.10063 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2020 Number of pages: 3-6 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Nathanel Amar, “Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music”, China Perspectives [Online], 2020-2 | 2020, Online since 01 June 2020, connection on 06 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/10063 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 10063 © All rights reserved Editorial china perspectives Contesting and Appropriating Chineseness in Sinophone Music NATHANEL AMAR he first special issue of China Perspectives on “Sinophone Musical itself as a more traditional approach to Chinese-sounding music but was Worlds” (2019/3) laid the theoretical foundation for a musical appropriated by amateur musicians on the Internet who subvert accepted T approach to Sinophone studies (Amar 2019). This first issue notions of Chinese history and masculinity (see Wang Yiwen’s article in this emphasised the importance of a “place-based” analysis of the global issue). Finally, the last article lays out in detail the censorship mechanisms for circulation of artistic creations, promoted in the field of Sinophone studies by music in the PRC, which are more complex and less monolithic than usually Shu-mei Shih (2007), and in cultural studies by Yiu Fai Chow and Jeroen de described, and the ways artists try to circumvent the state’s censorship Kloet (2013) as well as Marc Moskowitz (2010), among others. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

HOW BODY IMAGE INFLUENCES VOCAL PERFORMANCE in COLLEGIATE WOMEN SINGERS by Kirsten Shippert Brown Disser

MY BODY, MY INSTRUMENT: HOW BODY IMAGE INFLUENCES VOCAL PERFORMANCE IN COLLEGIATE WOMEN SINGERS by Kirsten Shippert Brown Dissertation Committee: Professor Randall Everett Allsup, Sponsor Professor Jeanne Goffi-Fynn Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date: May 19, 2021 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2021 ABSTRACT This dissertation is about the influence of body image on classical vocal performance in collegiate women singers. Those trained in classical singing are familiar with the phrase, “your body is your instrument.” A focus on the physical body is apparent in the vocal pedagogical literature, as is attention to singers’ mental and emotional states. But the intersection of emotions and the body—how one thinks and feels about their body, or body image—is largely absent from the vocal pedagogical literature. As voice teachers continue to necessarily address their students’ instruments (bodies), the field has not adequately considered how each singer’s relationship with their instrument (their body) might affect them, as singers and as people. This initial foray sought answers to just two of the myriad unanswered questions surrounding this topic: Does a singer’s body image influence her singing? If so, when and how? It employed a feminist methodological framework that would provide for consciousness-raising as both a method and aim of the study. Four collegiate women singers served as co-researchers, and data collection took place in three parts: a focus group, audio diaries, and interviews. The focus group was specifically geared towards consciousness-raising in order to provide co-researchers with the awareness necessary for examining their body image. -

Somalia's Judeao-Christian Heritage 3

Aram Somalia's Judeao-Christian Heritage 3 SOMALIA'S JUDEAO-CHRISTIAN HERITAGE: A PRELIMINARY SURVEY Ben I. Aram* INTRODUCTION The history of Christianity in Somalia is considered to be very brief and as such receives only cursory mention in many of the books surveying this subject for Africa. Furthermore, the story is often assumed to have begun just over a century ago, with the advent of modem Western mission activity. However, evidence from three directions sheds light on the pre Islamic Judeao-Christian influence: written records, archaeological data and vestiges of Judeao-Christian symbolism still extant within both traditional 1 Somali culture and closely related ethnic groups • Together such data indicates that both Judaism and Christianity preceded Islam to the lowland Horn of Africa In the introduction to his article on Nubian Christianity, Bowers (1985:3-4) bemoans the frequently held misconception that Christianity only came recently to Africa, exported from the West. He notes that this mistake is even made by some Christian scholars. He concludes: "The subtle impact of such an assumption within African Christianity must not be underestimated. Indeed it is vital to African Christian self-understanding to recognize that the Christian presence in Africa is almost as old as Christianity itself, that Christianity has been an integral feature of the continent's life for nearly two thousand years." *Ben I. Aram is the author's pen name. The author has been in ministry among Somalis since 1982, in somalia itself, and in Kenya and Ethiopia. 1 These are part of both the Lowland and Highland Eastern Cushitic language clusters such as Oromo, Afar, Hadiya, Sidamo, Kambata, Konso and Rendille. -

Civilisations from East to West

Civilisations from East to West Kinga Dévényi (ed.) Civilisations from East to West Corvinus University of Budapest Department of International Relations Budapest, 2020 Editor: Kinga Dévényi Tartalomjegyzék Szerkesztette: Authors: LászlóDévényi Csicsmann Kinga (Introduction) Kinga Dévényi (Islam) Szerzők: Csicsmann László (Bevezető) Előszó �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 13 Mária DévényiIldikó Farkas Kinga (Japan) (Iszlám) (Japán) BernadettFarkas Lehoczki Mária (Latin Ildikó America) Lehoczki Bernadett (Latin-Amerika) Tamás Matura (China) Matura Tamás (Kína) 1. Bevezetés a regionális–civilizációs tanulmányokba: Az új világrend és a ZsuzsannaRenner Renner Zsuzsanna (India) (India) paradigmák összecsapása – Csicsmann László������������������������������������������� 15 Sz. Bíró Zoltán (Oroszország) Zoltán Sz. Bíró (Russia) 1.1. Bevezetés .............................................................................................. 15 Szombathy Zoltán (Afrika) 1.2. Az új világrend és a globalizáció jellegzetességei ................................ 16 ZoltánZsinka Szombathy László (Africa) (Nyugat-Európa, Észak-Amerika) 1.3. Az új világrend vetélkedő paradigmái ....................................................... 23 LászlóZsom Zsinka Dóra (Western (Judaizmus) Europe, North America) 1.4. Civilizáció és kultúra fogalma(k) és értelmezése(k) .................................. 27 ....................................................... 31 Dóra Zsom (Judaism) 1.5. -

Chinese Music Reality Shows: a Case Study

Chinese Music Reality Shows: A Case Study A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Zhengyuan Bi In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Television Management January 2017 ii © Copyright 2017 Zhengyuan Bi All Right Reserved. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my family and my friends, with a special feeling of gratitude to my loving parents, my friends Queena Ai, Eileen Zhou and Lili Mao, and my former boss Kenny Lam. I will always appreciate their love and support! iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank my thesis advisor Philip Salas and Television Management Program Director Al Tedesco for their great support and guidance during my studies at Drexel University. I would also like to thank Katherine Houseman for her kind support and assistance. I truly appreciate their generous contribution to me and all the students. I would also like to thank all the faculty of Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, all the classmates that have studied with me for these two years. We are forever friends and the best wishes to each of you! v Table of Contents DEDICATION ………………………………………………………………………………..iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………...iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………vii Chapter 1: Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 1.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………...3 1.2 Statement of the Problem…………………………………………….................................3 1.3 Background…………………………………………………………………………………4 1.4 Purpose of the study…………………………………………………………………….....5 -

Panel Pool 2

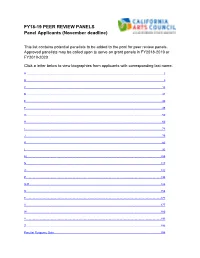

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Giving Voice Bro 09 2

International Festival of the Voice 2009 18 - 26 April, Wroclaw, Poland HARMONIC ACCORD: ENCOUNTERS THROUGH SONG SPOTKANIE W PIESNI´ 2 Giving Voice 11 stanowi specjaln edycję festiwalu; Giving Voice International Festival of the Voice współorganizuj go Center for Performance Research Contents z Walii oraz Instytut im. Jerzego Grotowskiego we Harmonic Accord Wrocławiu.Tegoroczny festiwal odbywa się w ramach Venues & Access - 2 obchodów Roku Grotowskiego 2009. Encounters through Song Przez 7 dni Wrocław będzie go´scił niespotykan ró˙znorodno´s´c tradycji Giving Voice 11: A festival of extraordinary voices from around the world including those from: Armenia, Austria, głosowych całego swiata:´ Armenii, Austrii, Korsyki, Gruzji, Gwinei, Iranu,Włoch, Harmonic Accord - 3 Corsica, Georgia, Guinea, Iran, Italy, Kurdistan, Mongolia, North America, Palestine, Poland, Kurdystanu, Mongolii, Ameryki Północnej, Palestyny, Polski, Sardynii, Serbii, Sardinia, Serbia, Spain, the Ukraine and Wales. Hiszpanii, Ukrainy oraz Walii. Calendar - 4 Poprzez dzielenie się ideami oraz praktyk w ramach ró˙znych warsztatów, How to Create Giving Voice springs from a strong events programmed for the Year of our questions embrace: aesthetics; pokazów i dyskusji, festiwal gromadzi praktyków, nauczycieli, teoretyków, belief in the voice’s ability to Grotowski 2009 in addition to this technique; the culturally specific; uzdrowicieli zainteresowanych prac z głosem, którzy niekoniecznie mieli Your Own Experience - 4 communicate beyond language and special edition of Giving Voice, matters of repertoire; archaism and the okazję do spotkania na drodze swej praktyki. Workshops - 5 - 14 cultural difference, and that working information of which may be found on relationship of tradition to innovation with the voice can allow people, from www.grotowski-institute.art.pl. -

A Quest to Champion Local Creativity

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Friday, December 13, 2019 | 21 LIFE SHANGHAI A quest to champion local creativity Shanghai Culture Square is ramping up efforts to promote Chinese musicals by establishing a research center for performances and productions, Zhang Kun reports. AIC Shanghai Culture The three winning plays from the Square announced on Dec 2 first incubation program consist of that it will host the second a thriller about a teenage survival Shanghai International game, a contemporary interpreta SMusical Festival in 2020 and join tion of the life of Li Yu, a legendary hands with new partners to pro poet from 1,000 years ago, and a mote the development of original fantasy love story involving time Chinese musical productions in travel. Shanghai. “We are still taking our first steps Shanghai has arguably been the in creating original musicals,” says largest and most developed market theater director Gao Ruijia, a men for musical shows in China. tor on the incubation program. According to the live show trade “You will only be able to achieve union of Shanghai, 292 musical steady development after you have performances took place in theaters mastered these first steps.” across the city in the first six There are as yet no plans to push months of 2019. These shows were any of these plays into the commer watched by more than 287,000 peo cial phase, but professor Jin Fuzai ple and had raked in more than 61 with the Shanghai Conservatory of million yuan ($8.68 million) in box Music, who is also a mentor on the office takings, more than any other incubation program, says that the sector in the theater industry. -

Two Generations of Contemporary Chinese Folk Ballad Minyao 1994-2017

Two Generations of Contemporary Chinese Folk Ballad Minyao 1994-2017: Emergence, Mobility, and Marginal Middle Class A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC July 2020 By Yanxiazi Gao Thesis Committee: Byong Won Lee, Chairperson Frederick Lau (advisor) Ricardo D. Trimillos Cathryn Clayton Keywords: Minyao, Folk Ballad, Marginal Middle Class and Mobility, Sonic Township, Chinese Poetry, Nostalgia © Copyright 2020 By Yanxiazi Gao i for my parents ii Acknowledgements This thesis began with the idea to write about minyao music’s association with classical Chinese poetry. Over the course of my research, I have realized that this genre of music not only relates to the past, but also comes from ordinary people who live in the present. Their life experiences, social statuses, and class aspirations are inevitably intertwined with social changes in post-socialist China. There were many problems I struggled with during the research and writing process, but many people supported me along the way. First and foremost, I am truly grateful to my advisor Dr. Frederick Lau. His intellectual insights into Chinese music and his guidance and advice have inspired me to keep moving throughout the entire graduate study. Professor Ricardo Trimillos gave frequent attention to my academic performance. His critiques of conference papers, thesis drafts, and dry runs enabled this thesis to take shape. Professor Barbara Smith offered her generosity and support to my entire duration of study at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. -

G.E.M.'S Powerful Vocals Thrill Fans at Venetian Macao

G.E.M.’s Powerful Vocals Thrill Fans at Venetian Macao Hong Kong young diva performs to sellout crowds at Cotai Arena (Macao, May 3, 2014) – Hong Kong pop music sensation G.E.M., also dubbed “Young Diva with Giant Lungs,” did not disappoint fans with her electrifying performances of G.E.M. X.X.X. Live World Tour – Macau, and once again showcased her signature, powerful vocals in front of a sellout crowd at The Venetian® Macao’s Cotai Arena for three consecutive evenings, concluding Saturday. Having returned to the Cotai Arena after her 2011 Macao debut, the Cantopop singer continued to enjoy huge popularity in the region, fuelled by her recent astonishing performance in China’s popular reality singing contest ““I Am a Singer.” G.E.M. once again successfully showcased at her Macao leg concerts her diverse musical talents and great versatility in a range of music styles, wooing fans by singing a selection of her number one hits like “A.I.N.Y.”, “Existing”, “You make me drunk” and also showing off her drumming and guitar skills on stage. The gigantic LED screen together with myriad lighting effects, including a surreal stream punk-themed scene in Victorian style, and a party scene back in the 70s to “get everybody moving” (the meaning of her stage moniker) were pleasant surprises to the audiences, filling the Cotai Arena with vitality and excitements. The rousing performances at the Cotai Arena were brought by a top-notch production team coupled with some of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians and stage professions, including music director Lupo Groinig from Austria; Jamie Wollam, onetime drummer for King of Pop Michael Jackson; sound engineer Matsunaga Tetsuya from Japan; and costume designer Emma Wallace from Great Britain.