“And for the Tea” by Jean Johnson, New York University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empires in East Asia

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Module 3 Empires in East Asia Essential Question In general, was China helpful or harmful to the development of neighboring empires and kingdoms? About the Photo: Angkor Wat was built in In this module you will learn how the cultures of East Asia influenced one the 1100s in the Khmer Empire, in what is another, as belief systems and ideas spread through both peaceful and now Cambodia. This enormous temple was violent means. dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. Explore ONLINE! SS.912.W.2.19 Describe the impact of Japan’s physiography on its economic and political development. SS.912.W.2.20 Summarize the major cultural, economic, political, and religious developments VIDEOS, including... in medieval Japan. SS.912.W.2.21 Compare Japanese feudalism with Western European feudalism during • A Mongol Empire in China the Middle Ages. SS.912.W.2.22 Describe Japan’s cultural and economic relationship to China and Korea. • Ancient Discoveries: Chinese Warfare SS.912.G.2.1 Identify the physical characteristics and the human characteristics that define and differentiate regions. SS.912.G.4.9 Use political maps to describe the change in boundaries and governments within • Ancient China: Masters of the Wind continents over time. and Waves • Marco Polo: Journey to the East • Rise of the Samurai Class • Lost Spirits of Cambodia • How the Vietnamese Defeated the Mongols Document Based Investigations Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Image with Hotspots: A Mighty Fighting Force Image with Hotspots: Women of the Heian Court 78 Module 3 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events 600–1400 Explore ONLINE! East and Southeast Asia World 600 618 Tang Dynasty begins 289-year rule in China. -

Building Railways in the People's Republic of China: Changing Lives

Building Railways in the People’s Republic of China Changing Lives Manmohan Parkash EARD Special Studies Building Railways in the People’s Republic of China: Changing Lives Manmohan Parkash © 2008 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the Philippines Publication Stock No. 092007 ISBN No. 978-971-561645-4 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank, of its Board of Governors, or of the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or the Asian Development Bank as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. ii Building Railways in the People’s Republic of China: Changing Lives Contents Contents .................................................................................. iii List of Tables and Figures .................................................................. iv Abbreviations and Acronyms .............................................................. v Acknowledgement ........................................................................ vi Foreword .................................................................................. vii Executive Summary ....................................................................... viii INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... -

Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns. International Journal of Sciences, Alkhaer, UK, 2013, 2 (11), pp.52-59. 10.18483/ijSci.334. hal- 02264434 HAL Id: hal-02264434 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02264434 Submitted on 8 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino, Italy Abstract: In the planning of some Chinese towns we can see an evident orientation with the cardinal direction north-south. However, other features reveal a possible orientation with the directions of sunrise and sunset on solstices too, as in the case of Shangdu (Xanadu), the summer capital of Kublai Khan. Here we discuss some other examples of a possible solar orientation in the planning of ancient towns. We will analyse the plans of Xi’an, Khanbalik and Dali. Keywords: Satellite Imagery, Orientation, Archaeoastronomy, China 1. Introduction different from a solar orientation with sunrise and Recently we have discussed a possible solar sunset directions. -

Mongolian Interest in Architecture and Construction in China (7Th C

REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION ISSN: 2146-0353 ● © RIGEO ● 11(4), WINTER, 2021 www.rigeo.org Research Article Mongolian Interest in Architecture and Construction in China (7th C. AH/ 13th C. AD) Prof. Dr. Suaad Hadi Hassan Al-Taai Department of History, College of Education ibn Rushd for Humanities, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq [email protected] Abstract The Mongols were interested in architecture and construction, whether in Mongolia or China, especially after they mixed with civilized peoples. They merged with them and were affected by their civilization and their arts, and they borrowed a lot from them, especially in the field of construction and architecture. After establishing his rule in China, Kublai (658-693 A.H., 1260-1294 A.D.) was keen on building a new capital for him, which he called Dadu, to replace his previous capital, Khanbaliq. After consulting with the wise men of his palace and astrologers, Kublai was interested in building luxurious palaces for himself and his family, and he used a large number of engineers and craftsmen to build them to be a model for contemporary cities and compete with them in architecture and luxury. Kublai gave several priorities to build his capital by providing it with large funds to provide all service institutions its residents need. He split rivers, built canals, reclaimed and cultivated lands, built roads, Keywords Kublai, Engineers, Walls, Rivers, The Capital, Princesses. To cite this article: Al-Taai, Prof.Dr, S, H, H.; (2021) Mongolian Interest in Architecture and Construction in China (7th C. AH/ 13th C. -

The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China

Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China Ringmar, Erik 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ringmar, E. (2013). Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China. Palgrave Macmillan. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Part I Introduction 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 1 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:311:06:31 PPMM 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 2 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:321:06:32 PPMM Chapter 1 Liberals and Barbarians Yuanmingyuan was the palace of the emperor of China, but that is a hope lessly deficient description since it was not just a palace but instead a large com- pound filled with hundreds of different buildings, including pavilions, galleries, temples, pagodas, libraries, audience halls, and so on. -

From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo. 2020. hal- 02563026 HAL Id: hal-02563026 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02563026 Preprint submitted on 5 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Politecnico di Torino Uploaded 21 April 2020 on Zenodo DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3759380 Abstract: In two previous papers (Philica, 2017, Articles 1097 and 1100), we investigated the travels of Marco Polo, using Google Earth and Wikimapia. We reconstructed the Polo’s travel from Beijing to Xanadu and from Sheberghan to Kashgar. Here we continue the analysis of this travel from today Kashgar to Xanadu. Keywords: Satellite Images, Google Earth, Wikimapia, Marco Polo, Taklamakan, Southwest Xinjiang, Lop Desert, Xanadu, Marco Polo, China. The Travels of Marco Polo is a 13th-century book writen by Rustchello da Pisa, reportng the stories told by Marco to Rustchello while they were in prison together in Genoa. This book is describing the several travels through Asia of Polo and the period that he spent at the court of Kublai Khan [1]. -

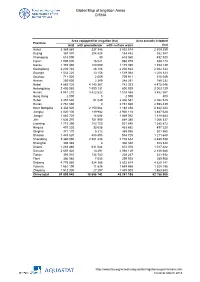

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Inner Asian States and Empires: Theories and Synthesis

J Archaeol Res DOI 10.1007/s10814-011-9053-2 Inner Asian States and Empires: Theories and Synthesis J. Daniel Rogers Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC (outside the USA) 2011 Abstract By 200 B.C. a series of expansive polities emerged in Inner Asia that would dominate the history of this region and, at times, a very large portion of Eurasia for the next 2,000 years. The pastoralist polities originating in the steppes have typically been described in world history as ephemeral or derivative of the earlier sedentary agricultural states of China. These polities, however, emerged from local traditions of mobility, multiresource pastoralism, and distributed forms of hierarchy and administrative control that represent important alternative path- ways in the comparative study of early states and empires. The review of evidence from 15 polities illustrates long traditions of political and administrative organi- zation that derive from the steppe, with Bronze Age origins well before 200 B.C. Pastoralist economies from the steppe innovated new forms of political organization and were as capable as those based on agricultural production of supporting the development of complex societies. Keywords Empires Á States Á Inner Asia Á Pastoralism Introduction The early states and empires of Inner Asia played a pivotal role in Eurasian history, with legacies still evident today. Yet, in spite of more than 100 years of scholarly contributions, the region remains a relatively unknown heartland (Di Cosmo 1994; Hanks 2010; Lattimore 1940; Mackinder 1904). As pivotal as the history of Inner Asia is in its own right, it also holds special significance for how we interpret complex societies on a global basis. -

Why Were Chang'an and Beijing So Different? Author(S): Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol

Why Were Chang'an and Beijing so Different? Author(s): Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 45, No. 4 (Dec., 1986), pp. 339-357 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/990206 Accessed: 07-04-2016 18:13 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 78.108.103.216 on Thu, 07 Apr 2016 18:13:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Why Were Chang'an and Beijing So Different? NANCY SHATZMAN STEINHARDT University of Pennsylvania Historians of premodern Chinese urbanism have long assumed that After stating the hypothesis of three lineages of Chinese imperial the origins of the Chinese imperial city plan stem from a passage in city building, the paper illustrates and briefly comments on the key the Kaogong Ji (Record of Trades) section of the classical text Rit- examples of each city type through history. -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ...................................................................................................................................................... -

The Role of Astronomy and Feng Shui in the Planning of Ming Beijing

Nexus Network Journal https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-021-00555-y RESEARCH The Role of Astronomy and Feng Shui in the Planning of Ming Beijing Norma Camilla Baratta1 · Giulio Magli2 Accepted: 19 April 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Present day Beijing developed on the urban layout of the Ming capital, founded in 1420 over the former city of Dadu, the Yuan dynasty capital. The planning of Ming Beijing aimed at conveying a key political message, namely that the ruling dynasty was in charge of the Mandate of Heaven, so that Beijing was the true cosmic centre of the world. We explore here, using satellite imagery and palaeomagnetic data analysys, symbolic aspects of the planning of the city related to astronomical alignments and to the feng shui doctrine, both in its “form” and “compass” schools. In particular, we show that orientations of the axes of the “cosmic” temples and of the Forbidden City were most likely magnetic, while astronomy was used in topographical connections between the temples and in the plan of the Forbidden City in itself. Keywords Archaeoastronomy of Ming Beijing · Forbidden City · Form feng shui · Compass feng shui · Ancient Chinese urban planning · Temple design Introduction In the second half of the fourteenth century, China sat in rebellion against the foreign rule of the Mongols, the Yuan dynasty. Among the rebels, an outstanding personage emerged: Zhu Yuanzhang, who succeeded in expelling the foreigners, proclaiming in 1368 the beginning of a new era: the Ming dynasty (Paludan 1998). Zhu took the reign title of Hongwu and made his capital Nanjing. -

Celebrating Traces of History Through Public Open Space Design in Beijing, China a Creative Project Submitted to the Graduate Sc

CELEBRATING TRACES OF HISTORY THROUGH PUBLIC OPEN SPACE DESIGN IN BEIJING, CHINA A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE BY LIN WANG CARLA CORBIN – COMMITTEE CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2014 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the three committee members of my creative project—Ms. Carla Corbin, Mr. Robert C. Baas, and Dr. Francis Parker—for their support, patience, and guidance. Especially Ms. Corbin, my committee chair, encouraged and guided me to develop this creative project. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Geralyn Strecker for her patience and assistance in my writing process. My thanks also extended to Dr. Bo Zhang—a Chinese Professor—who helped me figure out issues between Chinese and American culture. I would also like to express my gratitude to the faculty of the College of Architecture and Planning from whom I learned so much. Finally, special thanks to my family and friends for their love and encouragement during such a long process. The project would not have been completed without all your help. TABLE OF CONTENT CHAPTER1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Problem Statement ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Subproblems ....................................................................................................................................