Embodying Christ in the Bernward Gospels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The

Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 7: The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The Ministry for Islamic Affairs, Endowments, Da’wah, and Guidance, commonly abbreviated to the Ministry of Islamic Affairs (MOIA), supervises and regulates religious activity in Saudi Arabia. Whereas the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) directly enforces religious law, as seen in Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 1,1 the MOIA is responsible for the administration of broader religious services. According to the MOIA, its primary duties include overseeing the coordination of Islamic societies and organizations, the appointment of clergy, and the maintenance and construction of mosques.2 Yet, despite its official mission to “preserve Islamic values” and protect mosques “in a manner that fits their sacred status,”3 the MOIA is complicit in a longstanding government campaign against the peninsula’s traditional heritage – Islamic or otherwise. Since 1925, the Al Saud family has overseen the destruction of tombs, mosques, and historical artifacts in Jeddah, Medina, Mecca, al-Khobar, Awamiyah, and Jabal al-Uhud. According to the Islamic Heritage Research Foundation, between just 1985 and 2014 – through the MOIA’s founding in 1993 –the government demolished 98% of the religious and historical sites located in Saudi Arabia.4 The MOIA’s seemingly contradictory role in the destruction of Islamic holy places, commentators suggest, is actually the byproduct of an equally incongruous alliance between the forces of Wahhabism and commercialism.5 Compelled to acknowledge larger demographic and economic trends in Saudi Arabia – rapid population growth, increased urbanization, and declining oil revenues chief among them6 – the government has increasingly worked to satisfy both the Wahhabi religious establishment and the kingdom’s financial elite. -

The Perfect Choice! Salzgitter – Salzgitter – Die Bunte Familienstadt a Town of Striking Variety

Salzgitter – the perfect choice! Salzgitter – Salzgitter – die bunte Familienstadt a town of striking variety Salzgitter, die viertgrünste Stadt Deutschlands besticht Salzgitter is charmingly located among the Lower Saxon durch das große und naturnahe Freizeitangebot und foothills of the Harz Mountains. The fact that the town’s 31 freundliches Wohnen im Grünen. Die vielen Bürgerfeste, districts are surrounded by forests and fields means that Open Airs im Schloss Salder, aber auch die mittelalterli- nature is only ever a stone’s throw away. chen Märkte auf den Burgen Lichtenberg und Gebhards- hagen machen die Stadt so Lebens- und Liebenswert. Lake Salzgitter ranks as one of the town’s biggest attrac- tions, and has earned a reputation as the region’s premier Der Salzgitter See mit der Wasserskianlage, dem Piraten- water sports destination. It is located right next to the cen- spielplatz, der Eishalle und vielen weiteren kostenlosen tre of Lebenstedt – a large, modern district connected to Sporteinrichtungen ist das Aushängeschild in der Region the historic spa town of Salzgitter-Bad by the walker and und liegt in unmittelbarer Nähe des Stadtzentrums Le- cyclist-friendly Salzgitter Höhenzug Hills. Salzgitter-Bad is benstedt. Auch die kostenlosen Kindergärten sind einzig- the town’s second-largest district and greets visitors with artig in der Region und unterstreichen besonders die Fa- an enchanting collection of half-timbered buildings. Its milienfreundlichkeit. Der moderne Stadtteil Lebenstedt many smaller, village-like neighbourhoods also play an wird über den Lichtenberger Höhenzug, der zum Wan- important role in lending the town a special charm. dern und Mountenbiken einlädt, mit dem historischen Salzgitter Bad verbunden. -

Another Look at Cain: from a Narrative Perspective

신학논단 제102집 (2020. 12. 31): 241-263 https://doi.org/10.17301/tf.2020.12.102.241 Another Look at Cain: From a Narrative Perspective Wm. J McKinstry IV, MATS Adjunct Faculty, Department of General Education Presbyterian University and Theological Seminary In the Hebrew primeval histories names often carry significant weight. Much etymological rigour has been exercised in determining many of the names within the Bible. Some of the meaning of these names appear to have a consensus among scholars; among others there is less consensus and more contention. Numerous proposals have come forward with varying degrees of convincing (or unconvincing as the case may be) philological arguments, analysis of wordplays, possi- ble textual emendations, undiscovered etymologies from cognates in other languages, or onomastic studies detailing newly discovered names of similarity found in other ancient Semitic languages. Through these robust studies, when applicable, we can ascertain the meanings of names that may help to unveil certain themes or actions of a character within a narrative. For most of the names within the primeval histories of Genesis, the 242 신학논단 제102집(2020) meaning of a name is only one feature. For some names there is an en- compassing feature set: wordplay, character trait and/or character role, and foreshadowing. Three of the four members in the first family in Genesis, Adam, Eve, and Abel, have names that readily feature all the elements listed above. Cain, however, has rather been an exception in this area, further adding to Genesis 4’s enigmaticness in the Hebrew Bible’s primeval history. While three characters (Adam, Eve, and Abel) have names that (1) sound like other Hebrew words, that are (2) sug- gestive of their character or actions and (3) foreshadow or suggest fu- ture events about those characters, the meaning of Cain’s name does not render itself so explicitly to his character or his role in the narrative, at least not to the same degree of immediate conspicuousness. -

PROGRAM NOTES the Classical Master Josef Haydn and The

Program Notes The Classical master Josef Haydn and the idiosyncratic minimalist Arvo Pärt may seem like a musical odd couple, but this afternoon’s pairing brings to- gether two composers who share some fundamental characteristics. Both are men of a deep personal faith which is often reflected in their music. And both were unafraid to reference contemporary events in their music. Haydn’s title Missa in Tempore Belli (Mass in a Time of War) was his own, and refers to the Napoleonic wars, which were played out in large measure on Austrian soil. Pärt dedicated his 2008 Symphony No. 4 “Los Angeles” to Mikhail Khodoro- vsky, the Russian oil magnate, philanthropist, and vocal critic of the Putin government, whose imprisonment was widely thought to be politically mo- tivated, and his selection of the text for Adam’s Lament is his response to the ongoing tensions between Islamic and Christian worlds. Estonian-born Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) reinvented his compositional style after making an early name for himself as an avant garde composer. His early com- positions were fiercely atonal and serial, but he also experimented with aleatoric music, where he might indicate the range of pitches for a given voice but not specify discrete pitches, rhythms or durations, and collage music, in which he layered phrases of music from composers like Bach onto his own 12- tone music. The premiere of Pärt’s 1968 Credo, a choral collage piece, caused something of an uproar. The use of the liturgical text had not been approved by the Soviet composers’ union and the work was subsequently banned in the Soviet Union. -

Hildesheim.Pdf

Auftraggeber: Stadt Hildesheim Projektverantwortliche: Andrea Döring Stadtbaurätin Sandra Brouër Fachbereichsleiterin Stadtplanung und Stadtentwicklung Patrick Prause Bereich Stadtentwicklung – Verkehrsplanung Michael Veenhuis Bereichsleiter Stadtentwicklung – Projektleitung Auftragnehmer: Dr. Peter Bischoff SHP Ingenieure GbR AP 1, 3, 5 Melissa Latzel SHP Ingenieure GbR AP 1, 3, 5 Jürgen Allesch eM-Pro Elektromobilität GmbH AP 2 Burkhard Eberwein eM-Pro Elektromobilität GmbH AP 2 Helge Spies LNC LogisticNetwork Consultants GmbH AP 4 Dag Rüdiger LNC LogisticNetwork Consultants GmbH AP 4 Matthias Puffe Becker Büttner Held Consulting AG AP 6, 8 Dr. Florian Umlauf Becker Büttner Held Consulting AG AP 6, 8 Marius Goffart Becker Büttner Held Consulting AG AP 6, 8 Matthias Hartwig Institut für Klimaschutz, Energie und Mobilität AP 7 Felix Nowack Institut für Klimaschutz, Energie und Mobilität AP 7 Oskar Schumacher Institut für Klimaschutz, Energie und Mobilität AP 7 Projektleitung: Dr. Florian Umlauf Projektsteuerung: Andrea Döring Sandra Brouër Dr. Peter Bischoff Michael Veenhuis Dr. Florian Umlauf Matthias Puffe Green City Plan Hildesheim Verzeichnisse II Inhaltsverzeichnis Abbildungsverzeichnis ...................................................................................................... IX Tabellenverzeichnis........................................................................................................... X 1 Kurzzusammenfassung .............................................................................................. -

Deutsche Bischofskonferenz Der Bischof Von Hildesheim Bischöfliches Generalvikariat Kirchliche Mitteilungen

3 23.07.2012 Deutsche Bischofskonferenz Satzungsänderung Katholische Altenhilfe Verlautbarungen der Deutschen im Bistum Hildesheim ...........................................73 Bischofskonferenz ............................................... 62 Niedersächsisches Gaststättengesetz Der Bischof von Hildesheim (NGastG) ............................................................... 74 Beschlüsse der Bundeskommission der Arbeitsrechtlichen Kommission Disclaimer im Homepage-Impressum .......,........., 75 vom 15. März 2012 ............................................. 62 Aufruf zur Wahl der Vertreter(innen) der Beschluss der Unterkommission der Dienstgeber in die Regionalkommissionen Regionalkommission Nord (Antrag 68) der Arbeitsrechtlichen Kommissionen des vom 03.07.2012 ................................................... 66 Deutschen Caritasverbandes 2012 ......................75 Feststellung des Jahresabschlusses 2011 Aufruf zur Wahl der Vertreter(innen) der und Entlastung des Generalvikars für Mitarbeiter(innen) in die Regional- das Haushaltsjahr 2011 ........................................ 67 kommissionen und die Bundes- kommissionen der Arbeitsrechtlichen Empfehlungsbeschluss der Kommissionen des Deutschen Bistums-KODA vom 02.05.2012 ........................ 68 Caritasverbandes .................................................. 76 Empfehlungsbeschluss der Diözesanmännerwallfahrt .................................... 78 Zentral-KODA vom 10.11.2011 .......................... 68 Kirchliche Mitteilungen Beschluss der Bistums-KODA vom 02.05.2012 -

January 2014 Ensign

OLD TESTAMENT PROPHETS ADAM “Few persons in all eternity have been more directly involved in the plan of salvation . than the man Adam.” 1 ost people know me as the first Because we chose to eat the fruit, God knew that the Fall would Mman to live on the earth, but we had to leave the garden and God’s happen—He sent Jesus Christ to many don’t know that I had a special presence. This is known as the Fall. atone for our sins and overcome responsibility before I came to the We became mortal, experienced both death so that we and our children earth. In the premortal existence, I led the good and the bad of life, and could return to Him.11 God’s armies against Satan’s armies brought children to in the War in Heaven,2 and I helped earth.10 Jesus Christ create the earth.3 I was known as Michael then, which means one “who is like God.” 4 God chose me to be the first man on the earth and placed me in the Garden of Eden, a paradise with many types of plants and ani- mals. He breathed into me “the breath of life” 5 and gave me a new name: Adam.6 God told my wife, Eve, and me not to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil.7 If we didn’t eat the fruit, we could stay in the garden and live forever, but we wouldn’t be able to “progress by experiencing opposition in mortality” 8 or have children.9 The choice was ours to make. -

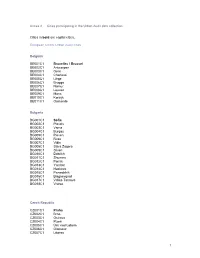

Annex 2 — Cities Participating in the Urban Audit Data Collection

Annex 2 — Cities participating in the Urban Audit data collection Cities in bold are capital cities. European Union: Urban Audit cities Belgium BE001C1 Bruxelles / Brussel BE002C1 Antwerpen BE003C1 Gent BE004C1 Charleroi BE005C1 Liège BE006C1 Brugge BE007C1 Namur BE008C1 Leuven BE009C1 Mons BE010C1 Kortrijk BE011C1 Oostende Bulgaria BG001C1 Sofia BG002C1 Plovdiv BG003C1 Varna BG004C1 Burgas BG005C1 Pleven BG006C1 Ruse BG007C1 Vidin BG008C1 Stara Zagora BG009C1 Sliven BG010C1 Dobrich BG011C1 Shumen BG012C1 Pernik BG013C1 Yambol BG014C1 Haskovo BG015C1 Pazardzhik BG016C1 Blagoevgrad BG017C1 Veliko Tarnovo BG018C1 Vratsa Czech Republic CZ001C1 Praha CZ002C1 Brno CZ003C1 Ostrava CZ004C1 Plzeň CZ005C1 Ústí nad Labem CZ006C1 Olomouc CZ007C1 Liberec 1 CZ008C1 České Budějovice CZ009C1 Hradec Králové CZ010C1 Pardubice CZ011C1 Zlín CZ012C1 Kladno CZ013C1 Karlovy Vary CZ014C1 Jihlava CZ015C1 Havířov CZ016C1 Most CZ017C1 Karviná CZ018C2 Chomutov-Jirkov Denmark DK001C1 København DK001K2 København DK002C1 Århus DK003C1 Odense DK004C2 Aalborg Germany DE001C1 Berlin DE002C1 Hamburg DE003C1 München DE004C1 Köln DE005C1 Frankfurt am Main DE006C1 Essen DE007C1 Stuttgart DE008C1 Leipzig DE009C1 Dresden DE010C1 Dortmund DE011C1 Düsseldorf DE012C1 Bremen DE013C1 Hannover DE014C1 Nürnberg DE015C1 Bochum DE017C1 Bielefeld DE018C1 Halle an der Saale DE019C1 Magdeburg DE020C1 Wiesbaden DE021C1 Göttingen DE022C1 Mülheim a.d.Ruhr DE023C1 Moers DE025C1 Darmstadt DE026C1 Trier DE027C1 Freiburg im Breisgau DE028C1 Regensburg DE029C1 Frankfurt (Oder) DE030C1 Weimar -

Frank Shurman Was Born Fritz Shürmann on January 8, 1915, in Hildesheim, Germany, to Willy and Alma Schürmann

Frank Shurman Visual History Biographic Profiles Frank Shurman was born Fritz Shürmann on January 8, 1915, in humiliation, they were sent to Buchenwald concentration camp with Hildesheim, Germany, to Willy and Alma Schürmann. He had two thousands of other Jewish men. sisters, Edith and Hanne-Lore. His father owned a Amid abysmal conditions, Frank maintained hope that men’s fashion business. In 1921, Frank started school through aid from Mrs. Hamilton, he and his father in a two-room Jewish primary school. Before the would be freed. After several months, first Willy and Nazis came to power, Frank experienced enough then Frank were released after signing papers stating antisemitism that he joined a boxing club to learn self- they had been well treated and wouldn’t speak of their defense. Frank later attended the Gymnasium, a imprisonment. In June 1939, while awaiting an European secondary school to prepare students for the emigration visa, Frank, with help from the British university. In 1932, as heir apparent to his father’s government, immigrated to England. In spring 1940, company, Frank became an apprentice tailor. Frank immigrated to the United States. While living in On April 1, 1933, on the day of the Nazi-organized New Jersey with an old friend from Hamburg, Frank nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned businesses, quickly found a job as a tailor and soon thereafter Frank traveled to the European Fashion Academy in Dresden, Germany, obtained a loan from Mrs. Hamilton to pay for his family’s passage to to complete his tailor training. That same year, Willy, a proud German America, forging a lifelong friendship between the two families. -

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON GENESIS 4:1–2 Why Did Cain Kill His Brother Abel?

CHAPTER ONE LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON GENESIS 4:1–2 You two are book-men: can you tell me by your wit; What was a month old at Cain’s birth, that’s not five weeks old as yet? (Shakespeare—Love’s Labor’s Lost 4.2.40) Why did Cain kill his brother Abel? It is usually assumed by modern commentators that God’s rejection of Cain’s offering led him to kill his brother in a fit of jealousy.1 Such a conclusion is logical in light of the way the action in the story is arranged. But the fact is we are never told the specific reason for the murder. Ancient exegetes, as we will see later, also speculated over Cain’s motive and sometimes provided the same conclusion as modern interpreters. But some suggested that there was something more sinister behind the killing, that there was something inborn about Cain that led him to earn the title of first murderer. These interpreters pushed back past the actual murder to look, as would a good biographer, at what it was about Cain’s birth and childhood that led him to his moment of infamy. Correspond- ingly, they asked similar questions about Abel. The result was a devel- opment of traditions that became associated with the brothers’ births, names and occupations. Who was Cain’s father? As we noted in the introduction, Cain and Abel is a story of firsts. In Gen 4:1 we find the first ever account of sexual relations between humans with the end result being the first pregnancy. -

![9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9536/9-the-mystical-bitter-water-trial-text-deleted-969536.webp)

9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]

9 The Mystical Bitter Water Trial [text deleted] 9.1 Golems as Archetypes of the Trial’s Supernaturally Inseminated Seed [text deleted] 9.2 Lilith as the First Sotah [text deleted] 9.3 Lilith and Samael as Animating Forces in Golems [text deleted] 9.4 Azazel as the Seed of Lilith No study of Lilith would be complete without a discussion of the demon Azazel. This is true because several clues in many ancient texts - including the Torah, the Zohar, and the First Book of Enoch - indicate that Azazel was the seed of Lilith. The texts further hint that Azazel was not the product of Lilith mating with any ordinary man, but rather he was the firstborn seed resulting from her illicit mating with Semjaza, the leader of a group of fallen angels called Watchers. As the seed of the Watchers, Azazel was the first born of the Nephilim, a race of powerful angel-man hybrids who nearly pushed ordinary mankind to extinction before the flood. But Azazel was much more than just a powerful Nephilim. Regular Nephilim were the products of the daughters of Adam mating with Watchers. Azazel was the product of Lilith mating with the Watchers. He is thus less human than all, and the most powerful, even more powerful than the Watchers who sired him. Azazel’s role in the Yom Kippur ceremony of Leviticus 16 indicates he is a rival to Messiah and God. This identifies Azazel as the legendary seed of the Serpent of Eden. God declared in his curse against the Serpent that this great seed would bruise the heel of Eve’s promised seed (Messiah), but Eve’s seed in turn would crush the head of the Serpent Lilith and destroy her seed. -

Fahrplan 2021 1

2021 FAHRPLAN 2021 1. Auflage, gültig ab 13. Dezember 2020 www.erixx.de FAHRPLAN RE10 RB47 RB37 erixx Kundenzentrum/ Bad Harzburg Uelzen Bremen Hbf Zug fahren ist einfach und sicher Fundbüro Goslar Stederdorf (Kr Uelzen) Bremen-Mahndorf Salzgitter-Ringelheim Wieren Achim Reisezentrum/Agentur Baddeckenstedt Bad Bodenteich Langwedel Video-Reisezentrum Derneburg Wittingen Visselhövede enno Servicecenter Groß Düngen Knesebeck Soltau Barrierefreier Bahnhof Tragen Sie einen Mund-Nasen-Schutz, Hildesheim Ost Vorhop Munster (Örtze) Hildesheim Hbf Schönewörde Brockhöfe Umstiegsmöglichkeit Sarstedt Wahrenholz Ebstorf halten Sie Abstand, kaufen Sie eine Fahrkarte! Hannover Hbf Triangel Uelzen Gifhorn Stadt RE10 Hannover Hbf – RB42 Gifhorn RB38 Hildesheim Hbf – Goslar – Bad Harzburg Braunschweig Hbf Rötgesbüttel Hannover Hbf RB42 Braunschweig Hbf – rkart Wolfenbüttel Meine Langenhagen Mitte Bad Harzburg Fah en Börßum Braunschweig-Gliesmarode Mellendorf RB43 Braunschweig Hbf – Goslar Schladen (Harz) Braunschweig Hbf Lindwedel RB47 Uelzen – Gifhorn – Braunschweig Hbf Vienenburg Schwarmstedt RB32 Lüneburg – Dannenberg Bad Harzburg RB32 Hodenhagen Ost Lüneburg Walsrode RB37 Bremen Hbf - Soltau (Han) - RB43 Wendisch Evern Bad Fallingbostel Uelzen Braunschweig Hbf Vastorf Dorfmark RB38 Hannover Hbf - Soltau (Han) - Wolfenbüttel Bavendorf Soltau Buchholz (Nordheide) - Börßum Dahlenburg Soltau Nord Abstand Maske tragen, Hamburg-Harburg erst aussteigen, Fahrkarte kaufen Schladen (Harz) Neetzendorf Wolterdingen auch im Bahnhof dann einsteigen Vienenburg Göhrde