Sonority Effects in the Production of Fricative + Sonorant Clusters in Polish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phonological Use of the Larynx: a Tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière

Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière To cite this version: Jacqueline Vaissière. Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial. Larynx 97, 1994, Marseille, France. pp.115-126. halshs-00703584 HAL Id: halshs-00703584 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00703584 Submitted on 3 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Vaissière, J., (1997), "Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial", Larynx 97, Marseille, 115-126. PHONOLOGICAL USE OF THE LARYNX J. Vaissière UPRESA-CNRS 1027, Institut de Phonétique, Paris, France larynx used as a carrier of paralinguistic information . RÉSUMÉ THE PRIMARY FUNCTION OF THE LARYNX Cette communication concerne le rôle du IS PROTECTIVE larynx dans l'acte de communication. Toutes As stated by Sapir, 1923, les langues du monde utilisent des physiologically, "speech is an overlaid configurations caractéristiques du larynx, aux function, or to be more precise, a group of niveaux segmental, lexical, et supralexical. Nous présentons d'abord l'utilisation des différents types de phonation pour distinguer entre les consonnes et les voyelles dans les overlaid functions. It gets what service it can langues du monde, et également du larynx out of organs and functions, nervous and comme lieu d'articulation des glottales, et la muscular, that come into being and are production des éjectives et des implosives. -

Sonorants, Fricatives and a Tonogenetic Typology

Sonorants, fricatives and a tonogenetic typology Gwendolyn Hyslop University of Oregon 1. Introduction and background While some phonological mechanisms underlying tonogenesis have been understood for some time (e.g. Maspero (1912), Haudricourt (1954), inter alia ) ongoing research in tonogenesis suggests that the full picture is more complex than previous studies have indicated. For example, though it is generally established that voiceless initials yield high pitch register, voiced initials yield low pitch register and coda consonants condition pitch contour, the order in which segments undergo tonogenesis has barely been addressed. Additionally, tone may be conditioned by other factors such as pre-aspiration or vowel quality, amongst others. The classical account of tonogenesis has been the model proposed by Haudricourt (1954) for Vietnamese. Diffloth (1989) reanalyzed the model to take register differences into account and Thurgood (2002) suggested updating our model of (Vietnamese) tonogenesis based on laryngeal features, arguing that intermediate stages existed. For example, voiced obstruents would condition breathy voice on their following vowel, which would in turn condition low tone. It remains to be seen, however, how much predictive power this model has, especially given recent research on tonogenesis in Kurtöp and the other East Bodish languages (Hyslop 2009, 2010), showing that tonogenesis targets sonorants and then fricatives before developing following obstruent consonants, a finding similar to that for Athabaskan (Kingston 2005, 2007). ‘Tone’ refers to the primary use of fundamental frequency to make lexical/grammatical contrasts in a given language (other acoustic cues may be involved, such as voice quality, duration, etc.). This definition includes most languages which have been classified as ‘pitch- accent’, as well as (possibly) languages which are considered to have a ‘register’ distinction (cf. -

A North Caucasian Etymological Dictionary

S. L. Nikolayev S. A. Starostin A NORTH CAUCASIAN ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY Edited by S. A. Starostin ***************** ****************ASTERISK PUBLISHERS * Moscow * 1994 The two volumes contain a systematic reconstruction of the phonology and vocabulary of Proto-North-Caucasian - the ancestor of numerous modern languages of the Northern Caucasus, as well as of some extinct languages of ancient Anatolia. Created by two leading Russian specialists in linguistic prehistory, the book will be valuable for all specialists in comparative linguistics and history of ancient Near East and Europe. © S. L. Nikolayev, S. A. Starostin 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editor' s foreword. , . Preface List of abbreviations Literature I ntr oduct ion Dictionary ? . 200 9 . 236 5 . , . ..............242 a' i ... ' 252 a ............. 275 b ...... 285 c 322 c 3 3 L t ^39 C 352 £ 376 : 381 d 397 e 409 4 2 5 Y 474 B 477 h 48 5 h 5 00 h 5 0 3 H 342 i 625 i 669 j '. 6 7 3 k. 68 7 fc 715 I 7 4 2 1 : .... 7 5 4 X. ! 7 5 8 X ; 766 X 7 7 3 L 7 86 t. ' 7 87 n 844 o. 859 p. 865 p. 878 q . 882 q 907 r. ..... 943 s... i 958 s. 973 S. 980 t . 990 t 995 ft. ...... 1009 u 1010 u 1013 V 1016 w. 1039 x 1060 X. ........ 1067 z. ... 1084 z 1086 2. 1089 3 1 090 3 1101 5 1105 I ndices. 1111 5 EDITOR'S FOREWORD This dictionary has a long history. The idea of composing it was already ripe in 1979, and the basic cardfiles were composed in 1980-1983, during long winter months of our collaboration with S. -

Classification of the Fricative and Occlusive Consonants According to the Place and the Mode of Articulation

International Journal of Electronics Communication and Computer Engineering Volume 9, Issue 1, ISSN (Online): 2249–071X Classification of the Fricative and Occlusive Consonants According to the Place and the Mode of Articulation Soufyane Mounir*, Karim Tahiry and Abdelmajid farchi Date of publication (dd/mm/yyyy): 03/03/2018 Abstract – In this article, we study the classification of Measurements on acoustic parameters that are reported for occlusive and fricatives consonants in standard modern the fricatives namely: spectral moments, F2onset Arabic for three different articulation sites: bilabial, alveolar frequency, locus equation, slope of the spectrum, location (dental) / interdental and velar. By calculating the four of spectral peaks, measurement of static and dynamic spectral moments after pretreatment of our speech signal, we amplitudes and the duration of the noise were based on can classify these consonants according to the place and the mode of articulation. discrete Fourier transforms [22 23 24]. They concluded that there is no invariance in the acoustic signal and, therefore, Keywords – A Fricative, Occlusive, Place of Articulation, the categorization of speech by the listeners requires a Spectral Moments massive integration of signals as well as mechanisms of compensation able to manage the contextual influences. I. INTRODUCTION Spinu and Lilley were interested in the classification of fricatives. For this, they examined two methods. From a Several methods can be adopted to improve the speech corpus of Romanian fricatives and for the coding of speech, recognition rate. Among these methods are the extraction of the first method is based on the comparison of two acoustic characteristics that are characterized by observation vectors measurements: the spectral moments and the cepstral determined by time methods such as linear predictive coefficients. -

Metathesis Is Real, and It Is a Regular Relation A

METATHESIS IS REAL, AND IT IS A REGULAR RELATION A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics By Tracy A. Canfield, M. S. Washington, DC November 17 , 2015 Copyright 2015 by Tracy A. Canfield All Rights Reserved ii METATHESIS IS REAL, AND IT IS A REGULAR RELATION Tracy A. Canfield, M.S. Thesis Advisor: Elizabeth C. Zsiga , Ph.D. ABSTRACT Regular relations are mathematical models that are widely used in computational linguistics to generate, recognize, and learn various features of natural languages. While certain natural language phenomena – such as syntactic scrambling, which requires a re-ordering of input elements – cannot be modeled as regular relations, it has been argued that all of the phonological constraints that have been described in the context of Optimality Theory can be, and, thus, that the phonological grammars of all human languages are regular relations; as Ellison (1994) states, "All constraints are regular." Re-ordering of input segments, or metathesis, does occur at a phonological level. Historically, this phenomenon has been dismissed as simple speaker error (Montreuil, 1981; Hume, 2001), but more recent research has shown that metathesis occurs as a synchronic, predictable phonological process in numerous human languages (Hume, 1998; Hume, 2001). This calls the generalization that all phonological processes are regular relations into doubt, and raises other -

Sonority As a Primitive: Evidence from Phonological Inventories

Sonority as a Primitive: Evidence from Phonological Inventories Ivy Hauser University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 1. Introduction The nature of sonority remains a controversial subject in both phonology and phonetics. Previous discussions on sonority have generally been situated in synchronic phonology through syllable structure constraints (Clements, 1990) or in phonetics through physical correlates to sonority (Parker, 2002). This paper seeks to examine the sonority hierarchy through a new dimension by exploring the relationship between sonority and phonological inventory structure. The investigation will shed light on the nature of sonority as a phonological phenomenon in addition to addressing the question of what processes underlie the formation and structure of speech sound inventories. This paper will examine a phenomenon present in phonological inventories that has yet to be discussed in previous literature and cannot be explained by current theories of inventory formation. I will then suggest implications of this phenomenon as evidence for sonority as a grammatical primitive. The data described here reveals that sonority has an effect in the formation of phonological inventories by determining how many segments an inventory will have in a given class of sounds (voiced fricatives, etc.). Segment classes which are closest to each other along the sonority hierarchy tend to be correlated in size except upon crossing the sonorant/obstruent and consonant/vowel boundaries. This paper argues that inventories are therefore composed of three distinct classes of obstruents, sonorants, and vowels which independently determine the size and structure of the inventory. The prominence of sonority in inventory formation provides evidence for the notion that sonority is a phonological primitive and is not simply derived from other aspects of the grammar or a more basic set of features. -

Acoustic Characteristics of Aymara Ejectives: a Pilot Study

ACOUSTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF AYMARA EJECTIVES: A PILOT STUDY Hansang Park & Hyoju Kim Hongik University, Seoul National University [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Comparison of velar ejectives in Hausa [18, 19, 22] and Navajo [36] showed significant cross- This study investigates acoustic characteristics of linguistic variation and some notable inter-speaker Aymara ejectives. Acoustic measurements of the differences [27]. It was found that the two languages Aymara ejectives were conducted in terms of the differ in the relative durations of the different parts durations of the release burst, the vowel, and the of the ejectives, such that Navajo stops are greater in intervening gap (VOT), the intensity and spectral the duration of the glottal closure than Hausa ones. centroid of the release burst, and H1-H2 of the initial In Hausa, the glottal closure is probably released part of the vowel. Results showed that ejectives vary very soon after the oral closure and it is followed by with place of articulation in the duration, intensity, a period of voiceless airflow. In Navajo, it is and centroid of the release burst but commonly have released into a creaky voice which continues from a lower H1-H2 irrespective of place of articulation. several periods into the beginning of the vowel. It was also found that the long glottal closure in Keywords: Aymara, ejective, VOT, release burst, Navajo could not be attributed to the overall speech H1-H2. rate, which was similar in both cases [27]. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.2. Aymara ejectives 1.1. Ejectives Ejectives occur in Aymara, which is one of the Ande an languages spoken by the Aymara people who live Ejectives are sounds which are produced with a around the Lake Titicaca region of southern Peru an glottalic egressive airstream mechanism [26]. -

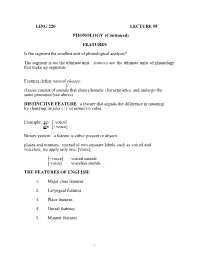

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is The

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? The segment is not the ultimate unit: features are the ultimate units of phonology that make up segments. Features define natural classes: ↓ classes consist of sounds that share phonetic characteristics, and undergo the same processes (see above). DISTINCTIVE FEATURE: a feature that signals the difference in meaning by changing its plus (+) or minus (-) value. Example: tip [-voice] dip [+voice] Binary system: a feature is either present or absent. pluses and minuses: instead of two separate labels, such as voiced and voiceless, we apply only one: [voice] [+voice] voiced sounds [-voice] voiceless sounds THE FEATURES OF ENGLISH: 1. Major class features 2. Laryngeal features 3. Place features 4. Dorsal features 5. Manner features 1 1. MAJOR CLASS FEATURES: they distinguish between consonants, glides, and vowels. obstruents, nasals and liquids (Obstruents: oral stops, fricatives and affricates) [consonantal]: sounds produced with a major obstruction in the oral tract obstruents, liquids and nasals are [+consonantal] [syllabic]:a feature that characterizes vowels and syllabic liquids and nasals [sonorant]: a feature that refers to the resonant quality of the sound. vowels, glides, liquids and nasals are [+sonorant] STUDY Table 3.30 on p. 89. 2. LARYNGEAL FEATURES: they represent the states of the glottis. [voice] voiced sounds: [+voice] voiceless sounds: [-voice] [spread glottis] ([SG]): this feature distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated consonants. aspirated consonants: [+SG] unaspirated consonants: [-SG] [constricted glottis] ([CG]): sounds made with the glottis closed. glottal stop [÷]: [+CG] 2 3. PLACE FEATURES: they refer to the place of articulation. -

Children's Auditory-Perceptual Performance in Identifying Phonological Contrasts Among Stops

Artigo Original Desempenho perceptivo-auditivo de crianças na Original Article identificação de contrastes fonológicos entre as oclusivas Larissa Cristina Berti1 Ana Elisa Falavigna2 Jéssica Blanca dos Santos2 Children’s auditory-perceptual performance in identifying Rita Aparecida de Oliveira2 phonological contrasts among stops Descritores RESUMO Percepção auditiva Objetivo: Investigar o desempenho perceptivo-auditivo de crianças no tocante à identificação de contrastes Avaliação entre as oclusivas; identificar quais fonemas e contrastes oclusivos apresentam maior ou menor grau de dificul- Fala dade de identificação; e verificar se a idade influencia a acurácia perceptivo-auditiva. Métodos: Foram selecio- Fonética nadas, de um banco de dados, informações referentes ao desempenho perceptivo-auditivo de 59 crianças (30 do Criança gênero masculino e 29 do gênero feminino) em uma tarefa de identificação da classe das consoantes oclusivas do Português Brasileiro. A tarefa consistiu na apresentação do estímulo acústico, por meio de fones de ouvido, e na escolha da gravura correspondente à palavra apresentada, dentre duas possibilidades de gravuras dispostas na tela do computador. O tempo de apresentação do estímulo e o tempo de reação das crianças foram computados automaticamente pelo software PERCEVAL. Resultados: Observou-se uma acurácia perceptivo-auditiva de 85% e uma correlação positiva com a idade. O tempo de resposta dos erros foi superior ao tempo de resposta dos acertos. De acordo com a matriz de confusão, houve contrastes de maior e menor dificuldade: pistas que marcam o vozeamento são mais robustas do que as pistas que marcam o ponto de articulação. Considerando apenas o ponto de articulação das consoantes oclusivas, observou-se uma assimetria perceptivo-auditiva, em que a distância fonética desempenha um papel fundamental na saliência perceptivo-auditiva. -

78. 78. Nasal Harmony Nasal Harmony

Bibliographic Details The Blackwell Companion to Phonology Edited by: Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice eISBN: 9781405184236 Print publication date: 2011 78. Nasal Harmony RACHEL WWALKER Subject Theoretical Linguistics » Phonology DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405184236.2011.00080.x Sections 1 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments 2 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with transparent segments 3 Nasal consonant harmony 4 Directionality 5 Conclusion ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Notes REFERENCES Nasal harmony refers to phonological patterns where nasalization is transmitted in long-distance fashion. The long-distance nature of nasal harmony can be met by the transmission of nasalization either to a series of segments or to a non-adjacent segment. Nasal harmony usually occurs within words or a smaller domain, either morphologically or prosodically defined. This chapter introduces the chief characteristics of nasal harmony patterns with exemplification, and highlights related theoretical themes. It focuses primarily on the different roles that segments can play in nasal harmony, and the typological properties to which they give rise. The following terminological conventions will be assumed. A trigger is a segment that initiates nasal harmony. A target is a segment that undergoes harmony. An opaque segment or blocker halts nasal harmony. A transparent segment is one that does not display nasalization within a span of nasal harmony, but does not halt harmony from transmitting beyond it. Three broad categories of nasal harmony are considered in this chapter. They are (i) nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments, (ii) nasal vowel– consonant harmony with transparent segments, and (iii) nasal consonant harmony. Each of these groups of systems show characteristic hallmarks. -

An Autosegmental Account of Melodic Processes in Jordanian Rural Arabic

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3592 & P-ISSN: 2200-3452 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au An Autosegmental Account of Melodic Processes in Jordanian Rural Arabic Zainab Sa’aida* Department of English, Tafila Technical University, P.O. Box 179, Tafila 66110, Jordan Corresponding Author: Zainab Sa’aida, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This study aims at providing an autosegmental account of feature spread in assimilatory situations Received: October 02, 2020 in Jordanian rural Arabic. I hypothesise that in any assimilatory situation in Jordanian rural Arabic Accepted: December 23, 2020 the undergoer assimilates a whole or a portion of the matrix of the trigger. I also hypothesise Published: January 31, 2021 that assimilation in Jordanian rural Arabic is motivated by violation of the obligatory contour Volume: 10 Issue: 1 principle on a specific tier or by spread of a feature from a trigger to a compatible undergoer. Advance access: January 2021 Data of the study were analysed in the framework of autosegmental phonology with focus on the notion of dominance in assimilation. Findings of the study have revealed that an undergoer assimilates a whole of the matrix of a trigger in the assimilation of /t/ of the detransitivizing Conflicts of interest: None prefix /Ɂɪt-/, coronal sonorant assimilation, and inter-dentalization of dentals. However, partial Funding: None assimilation occurs in the processes of nasal place assimilation, anticipatory labialization, and palatalization of plosives. Findings have revealed that assimilation occurs when the obligatory contour principle is violated on the place tier. Violation is then resolved by deletion of the place node in the leftmost matrix and by right-to-left spread of a feature from rightmost matrix to leftmost matrix. -

Becoming Sonorant

Becoming sonorant Master Thesis Leiden University Theoretical and Experimental Linguistics Tom de Boer – s0728020 Supervisor: C. C. Voeten, MA July 2017 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Sonority ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The usage of [sonorant] ................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Influence of sonority ..................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Structure ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Database study...................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Method ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Results ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3.1 Global Results .......................................................................................................................