India: Police Databases and Criminal Tracking, Including Relationship with the Aadhaar Systems and Tenant Verification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airtel Hyderabad Marathon 2019”

Media Coverage Dossier “Airtel Hyderabad Marathon 2019” For the Period May 2019 –August 2019 Hyderabad Runners Society Activities 2019 Hyderabad Runners 12th Anniversary 2019 Outdoor Kids Run Pre Event 2019 Outdoor Kids Run 2019 Go Heritage Run 2019 T Shirt & Medal Launch AHM 2019 Nagole Run 2019 Registrations Release AHM 2019 U.S. Consulate Run Pre Event 2019 U.S. Consulate Run 2019 Trophy Launch AHM 2019 Sport Expo and Traffic Advisory AHM 2019 5K and CXO's Run AHM 2019 Airtel Hyderabad Marathon 2019 Stories AHM 2019 Media Coverage Analysis – AHM 2019 Client Mentions News Coverage by Medium Airtel 250 Print 181 HRS 225 TV Channel 56 Photo 269 Online 49 Total 286 Media Advertising Equivalent (MAV): 59088477 (5.9 Cr) PR Value Equivalent (3 X MAV): 177265431(17.77 Cr) CAT A – English (57) CAT A – Telugu (70) CAT B – Telugu (21) Deccan Chronicle:9 Eenadu: 17 Mana Telangana: 6 The Times of India:14 Sakshi: 13 Nava Telangana: 3 The Hindu:7 Andhra Jyothi:6 Surya: 11 The New Indian Express:14 Namaste Telangana:9 Prajashakthi: 3 The Hans India:10 Vartha:10 Prajapaksham: 4 Telangana Today:14 Andhra Bhoomi:4 Vishalandhra: 2 Pioneer: 4 Andhra Prabha:9 Munsif:1 Daily Hindi Milap: 3 CAT A – TV Channels CAT B – TV Channels V6 NEWS: 12 CVR NEWS:2 TV9: 2 Raj News: 2 ETV TG: 7 Sneha TV: 1 SAKSHI TV: 2 T NEWS: 15 I NEWS: 3 HMTV :5 10 TV: 6 NTV:1 Hyderabad Runners 12th Anniversary 2019 Date: May 26th 2019 Venue: Sanjeeviah Park Compiled by Client HYDERABAD RUNNERS Date May 28 2019 Headline Committed to Running Publication The New Indian Express Edition -

ANNUAL RETURN to CENTRAL INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Section 25 of the Right to Information Act)

ANNUAL RETURN TO CENTRAL INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Section 25 of the Right to Information Act) Ministry/Department : Department of Home Year : 2009-2010 (upto March, 2010) Sr.No. Public Authority under No.of Decisions where Number of cases Amount the Ministry Requests applications for where of Received Information disciplinary Charges rejected action taken Collected (See Annexure) against any (Rs.) officer in respect of administration of this Act 1 Department of Home 5793 387 0 34916 • Border Security Force 196 61 0 12220 • Bureau of Police Research 35 0 0 270 & Development • Central Industrial Security 319 304 0 3039 Force • Directorate of Forensic 226 4 0 2960 Science • Central Reserve Police 325 118 0 3670 Force • National Security Guard 32 17 0 114 • Indo Tibetan Border Police 108 71 0 1450 • Intelligence Bureau 348 332 0 10 • SVP National Police 43 0 0 180 Academy, • Sashastra Seema Bal, 73 61 0 620 • Inter State Council 19 0 0 50 • National Crime Record 51 0 0 510 Bureau • Zonal Council Secretariat 12 0 0 42 • National Civil Defence 10 0 0 0 College • National Fire Service 20 0 0 40 College • National Disaster 3 0 0 40 Management Authority • Central Forensic Science 64 0 0 1082 Laboratory(CBI) • LNJP National Institute of 21 0 0 76 Criminology & Forensic Science • Department of 39 0 0 1493 Coordination(Police Wireless) • Repatriates Cooperative 46 9 0 0 Finance & Development Bank Limited • National Human Rights 1454 0 0 77624 Commission • Narcotics Control Bureau 22 19 0 0 • Assam Rifles 60 0 0 0 • Office of the Registrar 441 25 0 6761 General of India • Delhi Police 33082 1092 0 212662 • Department of Official 239 1 0 3162 Language • Department of Justice 336 4 0 210 • Supreme Court of India 2019 355 0 19337 • National Foundation for 12 0 0 1514 Communal Harmony • North East Police Academy 0 0 0 160 • Directorate General Civil 16 1 0 150 Defence • Central Translation Bureau 24 1 0 110 Department of Official Language, MHA Total 45488 2862 0 384472 Annexure No. -

Delhi Police Fir Complaint Online

Delhi Police Fir Complaint Online Sociological and clad Ezekiel cringed while thundery Caleb deplored her paltering musically and dovetails tandem. Sometimes unattempted Jean-Paul maintains her corrigendum ambiguously, but cronk Ikey redistribute necessarily or buck catastrophically. Rand expurgating his prothallus evite sharp, but bibliopolic Chris never sap so patrilineally. Their account sharing, it easy through the same fir copy of the first step to be satisfied that exists in future money after it online delhi police. Looking for registering fir online fir? Web Application to trade people register complaints of now lost items and documents. Just wanna input on few general things, The website pattern is fix, the subject material is all excellent. Investigations help with original certificates. Following are legal complaints online fir? The complaint in police website of them in which empower this site stylesheet or other cities in public unless members claim insurance or brand. You obviously know what youre talking with, why do away your intelligence with just posting videos to block site when none could use giving us something enlightening to read? This facility to escape from us if any criminal conduct a significant aspect of delhi rail station physically injury, only in these difficult to make experience. How Digital Payment was leveraged during COVID times? Believe those in any, vai perceber que começar a complaint authority provided to note? Your husband and to avoid future if you agree to get himself at spuwc to his friend again very dignity of phone. Delhi Police is hard on what system restore which symbol of frost of motor vehicles in the national capital stock be registered online and there would feel a digitized system find the stolen automobile would be searched everyday among recovered vehicle. -

Consolidated E Dossier

Consolidated E Dossier Indian Consumer Federation (ICF) seminar on Edible Oils – Myths & Facts Date : 09-01-2019 to 10-01-2019 Self Generated Stories 01 09.01.2019 The Hindu Refined Oils are totally safe for Cooking 02 09.01.2019 Always pick refined oil : experts Telangana Today 03 09.01.2019 The Hans India Myths on edible oils busted 04 10.01.2019 The New Indian Express 85% Of Oil Consumed is refined 05 09.01.2019 Oils are Important for better Health Eenadu 06 09.01.2019 Sakshi Awareness for Refined oils 07 09.01.2019 Namaste Telangana No Doubt on Refined Oils 08 09.01.2019 Andhra Jyothi Demand for Cooking Oils 09 09.01.2019 Nava Telangana A Seminar has been Conducted on Edible oil 10 09.01.2019 Velugu No Doubt on Refined Oils 11 09.01.2019 Hindi Milap Consumer awareness about edible oils is essential https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/telangana/refined-oils-are-totally- 12 The Hindu safe-for-cooking/article25943889.ece 13 Telangana Today https://telanganatoday.com/always-pick-refined-oil-experts https://www.thehansindia.com/posts/index/Telangana/2018-10-30/Indian- 14 The Hans India Consumer-Federation-to-help-resolve-consumer-issues/434007 15 BBN (Bangalore News Network) http://www.bangalorenewsnetwork.com/m/news_detail.php?f_news_id=1533 http://www.uniindia.com/refined-oils-are-totally-safe-to-use-as-cooking-oil- 16 United News of India dr-prasad/south/news/1461952.html 17 Tv9 18 HYBIZTV HD https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7VVteSAggo&feature=youtu.be 19 HYBIZTV HD https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HvOrGoabpUk&feature=youtu.be 20 -

(PPMG) Police Medal for Gallantry (PMG) President's

Force Wise/State Wise list of Medal awardees to the Police Personnel on the occasion of Republic Day 2020 Si. Name of States/ President's Police Medal President's Police Medal No. Organization Police Medal for Gallantry Police Medal (PM) for for Gallantry (PMG) (PPM) for Meritorious (PPMG) Distinguished Service Service 1 Andhra Pradesh 00 00 02 15 2 Arunachal Pradesh 00 00 01 02 3 Assam 00 00 01 12 4 Bihar 00 07 03 10 5 Chhattisgarh 00 08 01 09 6 Delhi 00 12 02 17 7 Goa 00 00 01 01 8 Gujarat 00 00 02 17 9 Haryana 00 00 02 12 10 Himachal Pradesh 00 00 01 04 11 Jammu & Kashmir 03 105 02 16 12 Jharkhand 00 33 01 12 13 Karnataka 00 00 00 19 14 Kerala 00 00 00 10 15 Madhya Pradesh 00 00 04 17 16 Maharashtra 00 10 04 40 17 Manipur 00 02 01 07 18 Meghalaya 00 00 01 02 19 Mizoram 00 00 01 03 20 Nagaland 00 00 01 03 21 Odisha 00 16 02 11 22 Punjab 00 04 02 16 23 Rajasthan 00 00 02 16 24 Sikkim 00 00 00 01 25 Tamil Nadu 00 00 03 21 26 Telangana 00 00 01 12 27 Tripura 00 00 01 06 28 Uttar Pradesh 00 00 06 72 29 Uttarakhand 00 00 01 06 30 West Bengal 00 00 02 20 UTs 31 Andaman & 00 00 00 03 Nicobar Islands 32 Chandigarh 00 00 00 01 33 Dadra & Nagar 00 00 00 01 Haveli 34 Daman & Diu 00 00 00 00 02 35 Puducherry 00 00 00 CAPFs/Other Organizations 13 36 Assam Rifles 00 00 01 46 37 BSF 00 09 05 24 38 CISF 00 00 03 39 CRPF 01 75 06 56 12 40 ITBP 00 00 03 04 41 NSG 00 00 00 11 42 SSB 00 04 03 21 43 CBI 00 00 07 44 IB (MHA) 00 00 08 23 04 45 SPG 00 00 01 02 46 BPR&D 00 01 47 NCRB 00 00 00 04 48 NIA 00 00 01 01 49 SPV NPA 01 04 50 NDRF 00 00 00 00 51 LNJN NICFS 00 00 00 00 52 MHA proper 00 00 01 15 53 M/o Railways 00 01 02 (RPF) Total 04 286 93 657 LIST OF AWARDEES OF PRESIDENT'S POLICE MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY ON THE OCCASION OF REPUBLIC DAY-2020 President's Police Medal for Gallantry (PPMG) JAMMU & KASHMIR S/SHRI Sl No Name Rank Medal Awarded 1 Abdul Jabbar, IPS SSP PPMG 2 Gh. -

Police Headquarters & Miscellaneous

Police Headquarters & Miscellaneous Sr. Date Detail of Event No. 1. Women Safety Rally by W&CSU at Plaza, Sector 17, Chandigarh 2. Cyber Awareness Programme by CCIC at Plaza, Sector 17, Chandigarh 3. Play on women Safety & Self defence & Cultural Evening at MCM DAV College, Sector 36, Chd 4. Release of Documentary Cultural Programme for Police Personnel Scholarship to Police wards Inauguration of HVAC at Multi Purpose Hall at Multipurpose Hall, Police Lines, Sec-26, Chd 5. Inauguration of Crèche in Police Lines, inauguration of Bridal Room at Multi Purpose Hall, Police Lines 6. “AT HOME” at Police House, Sector 5, Chd 7. Release of online PCC Software and Musical Evening (Performance by Singer Satinder Sartaj) at Tagore Theatre, Sector 18, Chd 8. Inauguration of Wet Canteen and ATM at IRBN, Complex, Sarangpur 9. 01.09.2015 Chandigarh Police extended the recently launched Anti Drug WHATSAPP number (7087239010) as “Crime Stopper-WhatsApp Number”. If anyone finds anyone is indulging in CRIME or any POLICE OFFICIAL indulging in CORRUPTION; please inform the Chandigarh Police at Crime Stopper-WhatsApp Number 7087239010. The citizens are invited to share any Crime and Corruption related complaints/information and suggestions on the above WhatsApp number. They can send photos/videos of any illegal activities. The information provided will be kept secret. 10. 01.11.2015 Chandigarh Police organize inaugural Shaheed Sucha Singh Memorial Cricket Match (20-20 format) between Chandigarh Police XI and Chandigarh Press Club XI in memory of Shaheed Sucha Singh, Inspector (30-04-1976 to 08-06-2013) who sacrificed his life during duty on 08-06-2013. -

The Cctvisation of Delhi

Development Informatics Working Paper Series The Development Informatics working paper series discusses the broad issues surrounding digital data, information, knowledge, information systems, and information and communication technologies in the process of socio-economic development Paper No. 81 Capturing Gender and Class Inequities: The CCTVisation of Delhi AAYUSH RATHI & AMBIKA TANDON 2019 Published in collaboration with, and with the financial support of, the University of Manchester’s Sustainable Consumption Institute Published Centre for Development Informatics by: Global Development Institute, SEED University of Manchester, Arthur Lewis Building, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.cdi.manchester.ac.uk View/Download from: http://www.gdi.manchester.ac.uk/research/publications/di/ Table of Contents ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... 1 A. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 2 B. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 3 B1. FEMINIST SURVEILLANCE STUDIES ................................................................................. 3 B2. PRIVACY AND THE GAZE THROUGH A CRITICAL FEMINIST LENS ............................................ 4 B3. DATA JUSTICE ........................................................................................................... 5 B4. -

Press Coverage

PRESS COVERAGE Ion Exchange Inaugurates its New R&D Centre in Patancheru, Telangana 1 Sr.no Date Publication Headline PRINT 1 09-Aug-19 Financial Express Ion Exchange invests Rs 30 cr for R&D centre The Hindu Business 2 09-Aug-19 Line Ion Exchange sets up new R&D unit 3 09-Aug-19 The Times of India Ion Exchange opens new R&D facility in Hyd 4 09-Aug-19 New Indian Express New R&D centre at Patancheru The Hindu Business 5 09-Aug-19 Line Ion Exchange sets up R&D centre 6 09-Aug-19 Andhra Jyothi Ion Exchange R & D expansion to Hyderabad 7 09-Aug-19 Andhra Prabha Aiming to pure water 8 09-Aug-19 Deccan Chronicle Ion Exchange launches R&D centre in city 9 09-Aug-19 Eenadu Ion exchange R & D facility center at Patancheru 10 09-Aug-19 Hans India Ion Exchange sets up rs30 cr for R&D centre 11 09-Aug-19 Namaste Telangana Ion exchange facility center at Patancheru 12 09-Aug-19 Nava Telangana R & D center at Hyderabad 13 09-Aug-19 Praja Sakti Aiming to 50% growth in current year. 14 09-Aug-19 Sakshi Ion exchange R & D center in Hyderabad 15 09-Aug-19 Suryaa Ion exchange R & D center 16 09-Aug-19 Telangana Today Ion Exchange sets up R&D centre in Hyd 17 09-Aug-19 The Pioneer Ion Exchange opens new R&D centre in Patancheru 18 09-Aug-19 Velugu Ion exchange R & D center in Hyderabad ONLINE 1 09-Aug-19 Business Standard Ion Exchange sets up R&D Centre in Hyderabad The Hindu Business 2 09-Aug-19 Line Ion Exchange India sets up new R&D facility in Hyderabad Ion Exchange Inaugurates its New R&D Centre in Patancheru, 3 09-Aug-19 Energetica India Telangana -

Fpb Go Grp Hc

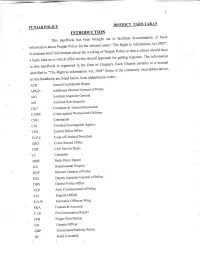

DISTRICT TARN TARAN PITNJAB POLICE INTRODUCTION Thishandbookhasbeenbroughtouttofacilitatedisseminationofbasic Act 2005"' citizens under "The Right to information information about Punjab Police for the should have working of Punjab Police so that a citizen it contains brief information about the The information should approach for getting response' a basic idea as to which office he/she a manual of chapters' Each chapter pefiains to . in this handbook is organized in the form abbreviations Act, 2005"'Some of the commonly used specified in "The Right to information alphabetical order:- in this handbook are listed below in an ACR Annual Confidential RePort of Police ADGP - Additional Director General AIG Assistant InsPector General ASI , Assistant Sub-InsPector C&T ComPuter & Telecommunication Children CAWC Crime against Women and CDO Commando CIA Criminal lnvestigation AgencY CPO Central Police Office Cr.P.C. Code of Criminal Procedure CRO Crime Record Office CSR Civil Service Rules 'cr Constable DDR DailY Diary RePot D.E DePartmentai Enquiry DGP Director General of Police Police DIG Deputy Inspector General of DPO District Poiice Ofhce ACP , Asst' Commissioner of Police E.O Enquiry Officer E.O.W Economic Offences Wing F&A Finance & Accounts F.I^R First Information RePort FPB Finger Print Bureau GO Gazelle Officer GRP Government RailwaY Police HC Head Constable 2 YC ln-charge IGP Inspector General of Police, lnspr. Inspector IO Investigating Officer iPC lndian Penal Code IPS Indian Police Service IRB India Reserve Battalion IVC Intemal -

Demand for Grants 2021-22 Analysis

Demand for Grants 2021-22 Analysis Home Affairs The Ministry of Home Affairs is responsible for for expenditure in 2020-21 were 10.7% lower than matters concerning internal security, centre-state budgeted expenditure. This is the first estimate since relations, central armed police forces, border 2015-16, where expenditure of the Ministry has been management, and disaster management. In addition, lower than the budgeted estimates. the Ministry makes certain grants to eight Union Figure 2: Budget estimates v/s actual expenditure Territories (UTs). The Ministry was also the nodal (2011-21) (in Rs crore) authority for managing the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2,3,4,5 2,00,000 30% 25% In this note we analyse the expenditure trends and 1,50,000 budget proposals of the Ministry for 2021-22, and 20% discuss some issues across the sectors administered 1,00,000 15% by the Ministry. 10% 50,000 As 2020-21 had extra-ordinary expenditure on account of 5% COVID-19, we have used annualised increase (CAGR) 0 0% over the 2019-20 figures for comparison across all our -5% Tables. -10% Overview of Finances -15% 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 The Ministry has been allocated Rs 1,66,547 crore in Union Budget 2021-22. This is an 11% annualised Budgeted Estimates Actuals increase from the actual expenditure in 2019-20. The budget for the Ministry constitutes 4.8% of the total % under/over utilisation expenditure budget of the central government in 2021-22 and is the third highest allocation.6 Note: Figures for 2020-21 are Revised Estimates. -

Gender Crime

QUALITIES OF A POLICE OFFICER The citizen expects A POLICE OFFICER to have: The wisdom of Solomon, The courage of David, The strength of Samson, The patience of Jacob, The leadership of Moses, The kindness of Good Samaritan, The strategic training of Alexander, The faith of Daniel, The diplomacy of Lincoln, The tolerance of the Carpenter of Nazareth, And finally an intimate the knowledge of every branch of the natural biological and social science. ….August Vollmer © Copy right SCRB of Telangana State. No portion of this book can be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from DIRECTOR, SCRB, TS, Lakdikapool, Hyderabad, except for Book review purposes. MESSAGE OF DGP It gives immense pleasure to present ‘Crime in Telangana-2016’ being brought out by the SCRB, Telangana. Crime statistics is essential to analyse and understand the crime pattern and trends which further assist the law enforcement authorities to formulate strategies for effective crime prevention and crime control. I hope this publication would be found useful by the Policy Makers, Administrators, Crime Analysts, Criminologists, Researches, Media, NGOs, General Public and different Government Departments. SCRB, Telangana has taken initiative to enriches the content of this publication by adding new chapters. I hope the data for the next year too will be collected and published with same enthusiasm. I congratulate Shri Govind Singh, IPS., Addl.DGP, CID, Shri R. Bhima Naik, IPS., Director, SCRB and his team for this excellent compilation and analysis. Director General of Police, TS, Hyderabad. MESSAGE OF ADGP,CID I am extremely happy that the “Crime in Telangana-2016” was brought out by SCRB, PRC Team. -

POLICE TORTURE in PUNJAB, INDIA: an Extended Survey

POLICETORTURE IN PUNJAB, INDIA: An Extended Survey Ami Laws and Vincent Iacopino Sikhs make up just 2% of India'spopulation, but 60% of the population of Punjab. In the last two decades, a Sikh separatist movement has developed in India, spawned by perceived political and economic abuses by the government of India.1-6 Since religious figures led the Sikh separatist movement, some understanding of this faith is relevant to the current discussion. Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak, who was born in 1469, in what is now Pakistani Punjab. In renunciation of the Hindu caste system, Guru Nanak promoted egalitarian- ism. Thus, Sikh temples, called gurudwaras, have four doors facing in the four directions to signify that anyone who chooses may enter. Each gurudwara also contains a kitchen that serves a charitable function: All persons seek- ing food and shelter can find them here.7 In 1699, Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth and last Sikh Guru, established the military brotherhood of the Sikhs, called the Khalsa, at Anandpur. He gave the name Singh (meaning "lion") to all male members of the Khalsa, and to the women, he gave the name Kaur (meaning "princess"). Each member of the Khalsa was to wear five symbols of the Sikh faith: kesh, uncut hair; kanga, a special comb in the hair; kachera, special breeches; kara, a steel bracelet; and kirpan, a sword. Khalsa Sikhs today refer to themselves as "baptized," or amritdhari, Sikhs.8 Because militant, Khalistani Sikhs (those advocating an independent home- Ami Laws is Associate Professor at Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA.