POLICE TORTURE in PUNJAB, INDIA: an Extended Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punjab – Christians – Hindus – Communal Violence – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND34243 Country: India Date: 30 January 2009 Keywords: India – Punjab – Christians – Hindus – Communal violence – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Is there conflict (including violence) between Hindus and Christians in Punjab? 2. To what extent is the government providing protection to victims of violence? 3. Are Christians discriminated against by the authorities? RESPONSE 1. Is there conflict (including violence) between Hindus and Christians in Punjab? 2. To what extent is the government providing protection to victims of violence? 3. Are Christians discriminated against by the authorities? Reports abound of conflict and violence between Hindus and Christians in India in general and to a less extent in Punjab while almost all the reports depict Hindus as the perpetrators. Several Christian organizations have recorded a large number of incidents of attacks on Christians by Hindus in recent years. One of them, Compass Direct News describes 2007 as the most violent year (US Department of State 2008, International Religious Freedom Report – India, 19 September, Section III – Attachment 1). In 2001, Amnesty International commented that: International attention continued to focus on violence against Christian minorities but victims of apparently state-backed violence in several areas included Muslims, dalits and adivasis (tribal people). -

India: Police Databases and Criminal Tracking, Including Relationship with the Aadhaar Systems and Tenant Verification

6/30/2020 Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Home Country of Origin Information Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) are research reports on country conditions. They are requested by IRB decision makers. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIR. Earlier RIR may be found on the European Country of Origin Information Network website . Please note that some RIR have attachments which are not electronically accessible here. To obtain a copy of an attachment, please e-mail us. Related Links Advanced search help 11 June 2020 IND200259.E India: Police databases and criminal tracking, including relationship with the Aadhaar systems and tenant verification; capacity to track persons through these systems (2019-June 2020) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada 1. Overview A Country Information Report on India by Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) states that India "does not have a centralised registration system in place to enable police to check the whereabouts of inhabitants in their own state, let alone in other states or union territories" (Australia 17 Oct. 2018, para. 5.20). Hanif Qureshi, the Inspector- General of Police in the state of Haryana, indicates that India does "not have any national [database] of criminals or gangs against which suspects can be identified" (Qureshi 9 Jan. 2020). The same source further indicates that police systems between districts and states are not integrated, creating "[i]slands of technology" which can only communicate within a state or district (Qureshi 9 Jan. -

Punjab: a Background

2. Punjab: A Background This chapter provides an account of Punjab’s Punjab witnessed important political changes over history. Important social and political changes are the last millennium. Its rulers from the 11th to the traced and the highs and lows of Punjab’s past 14th century were Turks. They were followed by are charted. To start with, the chapter surveys the Afghans in the 15th and 16th centuries, and by Punjab’s history up to the time India achieved the Mughals till the mid-18th century. The Sikhs Independence. Then there is a focus on the Green ruled over Punjab for over eighty years before the Revolution, which dramatically transformed advent of British rule in 1849. The policies of the Punjab’s economy, followed by a look at the Turko-Afghan, Mughal, Sikh and British rulers; and, tumultuous period of Naxalite-inspired militancy in the state. Subsequently, there is an account of the period of militancy in the state in the 1980s until its collapse in the early 1990s. These specific events and periods have been selected because they have left an indelible mark on the life of the people. Additionally, Punjab, like all other states of the country, is a land of three or four distinct regions. Often many of the state’s characteristics possess regional dimensions and many issues are strongly regional. Thus, the chapter ends with a comment on the regions of Punjab. History of Punjab The term ‘Punjab’ emerged during the Mughal period when the province of Lahore was enlarged to cover the whole of the Bist Jalandhar Doab and the upper portions of the remaining four doabs or interfluves. -

Police Headquarters & Miscellaneous

Police Headquarters & Miscellaneous Sr. Date Detail of Event No. 1. Women Safety Rally by W&CSU at Plaza, Sector 17, Chandigarh 2. Cyber Awareness Programme by CCIC at Plaza, Sector 17, Chandigarh 3. Play on women Safety & Self defence & Cultural Evening at MCM DAV College, Sector 36, Chd 4. Release of Documentary Cultural Programme for Police Personnel Scholarship to Police wards Inauguration of HVAC at Multi Purpose Hall at Multipurpose Hall, Police Lines, Sec-26, Chd 5. Inauguration of Crèche in Police Lines, inauguration of Bridal Room at Multi Purpose Hall, Police Lines 6. “AT HOME” at Police House, Sector 5, Chd 7. Release of online PCC Software and Musical Evening (Performance by Singer Satinder Sartaj) at Tagore Theatre, Sector 18, Chd 8. Inauguration of Wet Canteen and ATM at IRBN, Complex, Sarangpur 9. 01.09.2015 Chandigarh Police extended the recently launched Anti Drug WHATSAPP number (7087239010) as “Crime Stopper-WhatsApp Number”. If anyone finds anyone is indulging in CRIME or any POLICE OFFICIAL indulging in CORRUPTION; please inform the Chandigarh Police at Crime Stopper-WhatsApp Number 7087239010. The citizens are invited to share any Crime and Corruption related complaints/information and suggestions on the above WhatsApp number. They can send photos/videos of any illegal activities. The information provided will be kept secret. 10. 01.11.2015 Chandigarh Police organize inaugural Shaheed Sucha Singh Memorial Cricket Match (20-20 format) between Chandigarh Police XI and Chandigarh Press Club XI in memory of Shaheed Sucha Singh, Inspector (30-04-1976 to 08-06-2013) who sacrificed his life during duty on 08-06-2013. -

Role of Dalit Diaspora in the Mobility of the Disadvantaged in Doaba Region of Punjab

DOI: 10.15740/HAS/AJHS/14.2/425-428 esearch aper ISSN : 0973-4732 Visit us: www.researchjournal.co.in R P AsianAJHS Journal of Home Science Volume 14 | Issue 2 | December, 2019 | 425-428 Role of dalit diaspora in the mobility of the disadvantaged in Doaba region of Punjab Amanpreet Kaur Received: 23.09.2019; Revised: 07.11.2019; Accepted: 21.11.2019 ABSTRACT : In Sikh majority state Punjab most of the population live in rural areas. Scheduled caste population constitute 31.9 per cent of total population. Jat Sikhs and Dalits constitute a major part of the Punjab’s demography. From three regions of Punjab, Majha, Malwa and Doaba,the largest concentration is in the Doaba region. Proportion of SC population is over 40 per cent and in some villages it is as high as 65 per cent.Doaba is famous for two factors –NRI hub and Dalit predominance. Remittances from NRI, SCs contributed to a conspicuous change in the self-image and the aspirations of their families. So the present study is an attempt to assess the impact of Dalit diaspora on their families and dalit community. Study was conducted in Doaba region on 160 respondents. Emigrants and their families were interviewed to know about remittances and expenditure patterns. Information regarding philanthropy was collected from secondary sources. Emigration of Dalits in Doaba region of Punjab is playing an important role in the social mobility. They are in better socio-economic position and advocate the achieved status rather than ascribed. Majority of them are in Gulf countries and their remittances proved Authror for Correspondence: fruitful for their families. -

Kara Kaur Khalsa Baisakhi Gurdwara Singh Amrit Guru Nanak Kirpan Granthi Panj Pyare Gutkas Turban Guru Gobind Singh Akhand Path

Kara Kaur Khalsa Baisakhi Gurdwara Singh Amrit Guru Nanak Kirpan Granthi Panj pyare Gutkas Turban Guru Gobind Singh Akhand Path Teacher Chauri Romalas Kanga Amritsar Singh Kirpan Gurdwara Kara Granthi Chauri Gutkas Teacher Guru Gobind Singh Kanga Baisakhi Amritsar Khalsa Guru Nanak Kaur Akhand Path Teacher Amritsar Gutkas Baisakhi Gurdwara Akhand Path Guru Nanak Chauri Romalas Kara Kaur Gutkas Baisakhi Gurdwara Akhand Path Amrit Guru Nanak Romalas Granthi Panj pyare Singh Turban Guru Gobind Singh Kara Teacher Chauri Kanga Kanga Amritsar Gutkas Kirpan Gurdwara Khalsa Granthi Chauri Akhand Path Teacher Guru Gobind Singh Gutkas Baisakhi Amritsar Akhand Path Guru Nanak Kaur Romalas Teacher Amritsar Panj pyare Baisakhi Gurdwara Guru Gobind Singh Guru Nanak Chauri Kirpan Kara Granthi Guru Nanak Baisakhi Kaur Panj pyare Amrit Gurdwara Guru Gobind Singh Granthi Kara Kanga Turban Baisakhi Kirpan Teacher Amrit Granthi Kanga Chauri Teacher Kirpan Amritsar Baisakhi Granthi Gurdwara Guru Nanak Teacher Khalsa Gutkas Baisakhi Singh Akhand Path Guru Nanak Kirpan Romalas Teacher Kaur Singh Baisakhi Amritsar Kara Guru Nanak Gurdwara Gutkas Kara Chauri Kanga Baisakhi Gurdwara Khalsa Amrit Guru Nanak Akhand Path Amritsar Panj pyare Gutkas Gurdwara Guru Gobind Singh Akhand Path Chauri Gurdwara Romalas Kanga Amritsar Kara Kirpan Gurdwara Baisakhi Granthi Chauri Amrit Teacher Guru Gobind Singh Khalsa Baisakhi Amritsar Singh Guru Nanak Kaur Kirpan Teacher Amritsar Kanga Baisakhi Gurdwara Kirpan Guru Nanak Chauri Granthi Kara Kaur Granthi Baisakhi Gurdwara Turban -

The Khalsa and the Non-Khalsa Within the Sikh Community in Malaysia

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 8 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Khalsa and the Non-Khalsa within the Sikh Community in Malaysia Aman Daima Md. Zain1, Jaffary, Awang2, Rahimah Embong 1, Syed Mohd Hafiz Syed Omar1, Safri Ali1 1 Faculty of Islamic Contemporary Studies, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA) Malaysia 2 Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3222 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3222 Abstract In the pluralistic society of Malaysia, the Sikh community are categorised as an ethnic minority. They are considered as a community that share the same religion, culture and language. Despite of these similarities, they have differences in terms of their obedience to the Sikh practices. The differences could be recognized based on their division into two distintive groups namely Khalsa and non-Khalsa. The Khalsa is distinguished by baptism ceremony called as amrit sanskar, a ceremony that makes the Khalsa members bound to the strict codes of five karkas (5K), adherence to four religious prohibitions and other Sikh practices. On the other hand, the non-Khalsa individuals have flexibility to comply with these regulations, although the Sikhism requires them to undergo the amrit sanskar ceremony and become a member of Khalsa. However the existence of these two groups does not prevent them from working and living together in their religious and social spheres. This article aims to reveal the conditions of the Sikh community as a minority living in the pluralistic society in Malaysia. The method used is document analysis and interviews for collecting data needed. -

Festivals of the Sikh Faith

FESTIVALS OF THE SIKH FAITH Introduction Sikhism is the youngest of the great world faiths. There are 20-22 million Sikhs in the world, tracing the origin of their religion to Punjab, located in present-day Pakistan and northern India. Now the fifth largest in the world, the Sikh religion is strictly monotheistic, believing in one supreme God, free of gender, absolute, all pervading, eternal Creator. This universal God of love is obtained through grace, sought by service to mankind. Sikhism is a belief system that teaches justice, social harmony, peace and equality of all humanity regardless of religion, creed, and race. Sikhism places great value on human life as an opportunity to live the highest spiritual life through their religious commitment to honest living and hard work. Sikhs are students and followers of Guru Nanak (b.1469), the founder of the Sikh religious tradition, and the nine prophet-teachers – called Gurus – who succeeded him. Sikhs have their own divine scriptures collected in the Guru Granth Sahib, written by the Gurus themselves, which today serves as the eternal spiritual guide of the Sikhs. Besides the compositions of the Gurus, it also contains the writings of Hindu and Muslim saints. Sikh Festivals Sikh festivals are called gurpurabhs or days connected with important events in the lives of the Gurus. They are occasions for the re-dedication and revival of the Faith and are celebrated in a spirit of fellowship and devotion. They are usually celebrated at gurdwaras (Sikh place of worship), open to all men and women without distinction of caste, creed or colour. -

Fpb Go Grp Hc

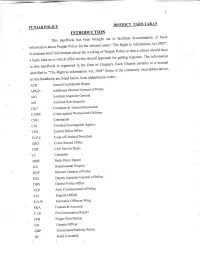

DISTRICT TARN TARAN PITNJAB POLICE INTRODUCTION Thishandbookhasbeenbroughtouttofacilitatedisseminationofbasic Act 2005"' citizens under "The Right to information information about Punjab Police for the should have working of Punjab Police so that a citizen it contains brief information about the The information should approach for getting response' a basic idea as to which office he/she a manual of chapters' Each chapter pefiains to . in this handbook is organized in the form abbreviations Act, 2005"'Some of the commonly used specified in "The Right to information alphabetical order:- in this handbook are listed below in an ACR Annual Confidential RePort of Police ADGP - Additional Director General AIG Assistant InsPector General ASI , Assistant Sub-InsPector C&T ComPuter & Telecommunication Children CAWC Crime against Women and CDO Commando CIA Criminal lnvestigation AgencY CPO Central Police Office Cr.P.C. Code of Criminal Procedure CRO Crime Record Office CSR Civil Service Rules 'cr Constable DDR DailY Diary RePot D.E DePartmentai Enquiry DGP Director General of Police Police DIG Deputy Inspector General of DPO District Poiice Ofhce ACP , Asst' Commissioner of Police E.O Enquiry Officer E.O.W Economic Offences Wing F&A Finance & Accounts F.I^R First Information RePort FPB Finger Print Bureau GO Gazelle Officer GRP Government RailwaY Police HC Head Constable 2 YC ln-charge IGP Inspector General of Police, lnspr. Inspector IO Investigating Officer iPC lndian Penal Code IPS Indian Police Service IRB India Reserve Battalion IVC Intemal -

Gurdwara Key Words Guru Granth Sahib 5 Ks in Sikhism Khalsa The

Gurdwara Key words A Gurdwara is a Sikhs place of worship. It houses the Memorise these key words. Guru Granth Sahib. Sikhs sit down in the prayer hall so they not above the Guru. They pray together as a Gurdwara – Sikh place of worship community. At the end of their service they will have a meal together. This is called the Langar. It is Guru – Religious teachers for Sikhs vegetarian food. Khalsa – Name given to Sikhs who are full members of the Sikh religion. Yr. 8 Learn Why do they serve vegetarian food? Sheet Guru Granth Sahib – Sikh holy book Assessment Baisakhi – Spring festival, which includes the Sikh point 2 New Year Sikhism In what other ways is the Gurdwara used? 1. Sewa – Service – helping others 2. 3. 4. 5 Ks in Sikhism The 5 Ks are: 1. Kesh (uncut hair) – a gift from God symbolises adoption of a simple life Guru Granth Sahib 2. Kara (a steel bracelet) – belief in a never ending God, every time Guru Gobind Singh decided that he would leave they look at it, it will remind them to avoid sin. the Sikh community to be guided by the writings 3. Kanga (a wooden comb) – it keeps the tangles out of their hair, gives and teachings of all the Gurus in written form. them hope that God will take the tangles out of their lives. The book is now treated in exactly the same way 4. Kaccha - also spelt, Kachh, Kachera (cotton underwear) – a symbol as a human leader would be. of chastity 5. Kirpan (steel sword) – a reminder to protect the faith and the vulnerable. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

Punjab, Haryana, Chandigarh and Himachal Pradesh, India

Punjab, Haryana, Chandigarh and Himachal Pradesh, India Market summary Golden Temple, Amritsar – The holiest shrine of the sikh religion Introduction Gurgaon - One of India’s largest Industrial/IT The region of Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal hubs. Its proximity to New Delhi means that it has Pradesh forms the heartland of Northern India and evolved as a major corporate hub with half of has amongst the highest per capita income in India. Fortune 500 companies having a base here The state of Punjab is the food basket and the Faridabad - Faridabad is an industrial hub of granary of India contributing to over 20 per cent of Haryana, for manufacturing tractors, motorcycles, India’s food production. Punjab is also the textile and and tyres manufacturing hub of Northern India. The state of Haryana has strong agricultural, food processing and education sectors. Together the states of Punjab & Punjab, Haryana, Chandigarh & Haryana have one of the largest dairy sectors. The state of Himachal Pradesh is renowned for Himachal – Key industry facts horticulture and tourism. Punjab Punjab produces around 10% of India's cotton, Quick facts 20% of India's wheat, and 11% of India's rice Punjab's dairy farming has 9% share in country's Area: 150349 sq. kms milk output with less than 2% livestock Population: 60.97 million Regional GDP: US$164 billion Haryana Haryana is 2nd largest contributor of wheat and Major cities 3rd largest contributor of rice to the national pool Haryana's dairy farming has 6% share in Chandigarh – Shared capital of the states of country's milk output Punjab and Haryana.