Pintail Owners' Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olympic Broach: E No Good Very Bad Windiest Day Two Races in Athens Shatter an Olympic Medal Dream

November 30th 2014 by Lenny Rudow Olympic Broach: e No Good Very Bad Windiest Day Two races in Athens shatter an Olympic medal dream. Day two of sailing at the 2004 Olympics started out just like day one: sunny and gaspingly hot, with only about three knots of wind. And just like the day before, I called up to the committee boat, “Good morning—USA.” At this regatta, I checked in not as myself or as the skipper of a three-person team, but as an entire country. What a rush. I remember that moment perfectly, but it’s taken me 10 years to swallow my pride enough to write about what followed. And I’m only going to do it once, so listen up. Day two started out very light and ended up very windy. Fortunately our Olympic branding held up to the change in conditions better than we did. Photo: ©DanielForster STARTING STRONG Th e Saronic Gulf rippled and heat-shimmered beneath the light easterly, which we hoped would build to meet the fi ve-knot minimum in time for racing. In similar conditions the day before, we’d fi nished second in the very fi rst race of our week-long event. So I’d chosen the same clothing: white long-sleeved shirt, light-colored leggings, white USA hat. Liz had gone with short sleeves and Nancy sported a tank top, but we were unifi ed by our Team USA regatta pinnies. And in case we forgot our last names, all we had to do was look up—they’d been stuck on the mainsail in bold letters, just below a large American fl ag. -

Wells/Kern Take Down Southern CC Regatta

Wells/Kern Take Down Southern CC Regatta Above: Wells/Kern (#1130) make a close cross as Hennon/Wallace tack away from the shore at the SCC. The 6th Southern Comfort Classic regatta kicked suited up five boats for the event, including one off Friday night with ASC members Lenny Wells helmed by Nicky Einthoven with crew Teri and Teri Fosmire sharing some alone time at the Fosmire, still glowing from her date with Lenny local pizza joint. We are still investigating the lack of enthusiasm for the annual darts and beer IN THIS ISSUE extravaganza, but preliminary indications point towards the absence of Dave “Plywood” Michos Southern Comfort Classic Pictures.……..…… 3 and Brent “It’s only a 5 hour drive to NC” Restoring a Classic (Part II) ………………4 Barbehenn as primary factors. Upcoming Regattas………………….…….…6 Classifieds…………………………..………… 6 The weather forecast was very promising for the President’s Corner……..…………………….7 entire weekend and did not disappoint. ASC Jet-14 Connect!.............……….……………...7 2 the previous evening. Lenny was joined by his ultimately could not recover and had to retire for rising junior star, Caswell Kern, while new Jet the day. Wells/Kern went on to take the next member Curtis Boyd was ready to give #203 its two races and secure the lead. first action of the year. Joining the ASC boats That night, the fleet enjoyed a wonderful was our regular traveler, Tom Grace and Paula evening at the local restaurant on the lake. They Pacheco (Lake Norman YC) in Wren, last were joined by several ASC club members for a renovated during the Eisenhower BBQ meal. -

Taming the Kite!

Taming the Kite! What goes wrong? Wineglass when launching – can happen in light or heavy weather Broaching on a reach – usually in heavy weather Death rolls – usually in heavy weather Gybing disasters – worse in heavy weather Wineglasses. Wineglasses occur when the top half of the kite fills before the bottom with a twist in the middle. Avoiding: Making sure the kite is not twisted before it is launched is a good start. Wineglasses can normally be avoided by getting the kite halyard up ASAP and opening the kite from the bottom by bringing pole back and then sheeting on as it goes up. Timing of sheet is important as filling the kite before it is fully up makes it difficult to get to the top! It is generally faster to pull the halyard from the mast rather than in the cockpit. If the kite is launched from a bag on the bow it is important to get the clews out and separated earlier. If the halyard is well on the way up before the clews are out of the bag then a wineglass is more likely to result. Fixing: If a wineglass occurs it can usually be fixed by the foreward hand pulling very hard down on the pole end luff from the bow (hanging their weight on it), at the same time easing the sheet a little. Letting a metre or so of halyard out sometimes helps as well (no idea why!!) In lighter winds the foreward hand can sometimes untwist the kite from the bow. If all else fails it will need to be partly dropped and re-launched. -

CATAMARAN POINTERS by Melcon June 2021

CATAMARAN POINTERS by Melcon June 2021 1. Basics a. Catamarans are intrinsically faster than monohulls because the narrow hulls do not produce bow and stern waves that limit the displacement speed max 푠푝푒푒푑 = 1.34√푤푎푡푒푟푙푖푛푒 b. Catamarans are intrinsically faster than monohulls because of their high righting moment due to the width of the boats. This righting moment allows them to carry more sail area. c. Monohulls can move out of displacement mode by planning but this still slow, approaching the speed of catamarans on boats like the Aussie 18s. d. Catamarans often have significantly greater sail area than monohulls because their width gives them tremendous righting moment. e. Catamarans “tip over easily” because they have a large canvas area and are often sailed poorly f. Catamarans do not point as high as monohulls because a higher VMG can be gained by footing. Catamarans can point as high as monohulls even though the often have l less efficient and smaller foils. g. The myth of catamarans being “difficult to tack” came about because of the popularity of two of the worst designs ever: Hobie 14 and Hobie 16. 2. Upwind a. Fast i. Flat is fast—keep the windward hull within 18 inches of the water ii. Keep the jib luff telltales streaming iii. Keep the main leech telltales streaming iv. Centerboards should be all the way down b. Depower i. Increase the downhaul to depower the main (flattening) ii. Increase the jib luff tension to depower the jib (flattening) iii. Progressively drop the traveler to depower iv. Increase twist in main (let out mainsheet) to depower v. -

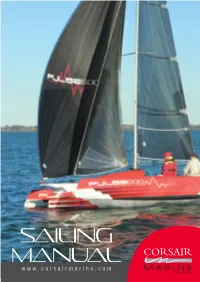

2017+Pulse-600-SAILING-MANUAL

SAILING MANUAL www.corsairmarine.com Sailing manual applicable to This manual has been compiled to help you to operate your craft with safety and enjoyment. It contains details of the craft; the equipment supplied or fitted; its systems, and information on its operation and maintenance. Please read it carefully and familiarize yourself with the craft before using it. If this is your first craft, or you are changing to a type of craft you are not familiar with, for your own comfort or safety, please ensure that you obtain handling and operating experience before assuming command of the craft. Your dealer or national sailing federation or yacht club will be pleased to advise you of local sailing schools or competent instructors. PLEASE KEEP THIS MANUAL IN SECURE PLACE, AND PASS ON TO THE NEW OWNER WHEN YOU SELL THE CRAFT Model: __________________________________________________________________________________________ Hull Number: _____________________________________________________________________________________ Owner1: _____________________ Owner2: _____________________ Owner3: _____________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ Built by: Corsair Marine International T: (+84 8) 3873 3620 | F: (+84 8) 3873 3621 E: [email protected] www.corsairmarine.com PAGE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL __________________________________________________________________ -

Fly Your Spinnaker with Confidence

Ex-Merchant Navy officer and Fellow of the Royal Institute of EXPERT ON BOARD Navigation, John Goode owned Southern Sailing School for 25 EXPERT ON BOARD years and is an RYA Examiner What goes where? TH EA H NE End for end pole XI a If you haven’t flown a spinnaker MS: M MS: before, you and your crew will put a R to sea with a lot more confidence if AG I d you work out where everything goes, Fly your spinnaker de. and that it all works, while still tied to oo the dock. Choose a berth with a light End for end n g n wind on the quarter and take as long pole with oh double as required to set the rig up to the sheets and pre-hoist stage – and even better if guys the wind is so light that the spinnaker all PHOTOS: j PHOTOS: all can be hoisted and dropped as well. with confidence Note that although the bottom two Advice from John Goode on corners of a spinnaker are labelled ‘tack’ and ‘clew’, these names change hoisting, trimming, dropping when the sail is gybed. Throughout this article, the tack is always named and packing your kite as the corner of the spinnaker being hauled back by the pole – and the n light conditions, a spinnaker should give clew the corner that’s attached to above: before flying a spinnaker for the first time, I advise better downwind performance than any the working sheet. practising setting it up before leaving the dock other sail. -

Corsair Sailing Manual

SAILING MANUAL 28 24 For All Corsair Models November, 1997 Sailing Manual For All Corsair Models Including F-24, F-28 and F-31 This manual has been compiled to help you to operate your craft with safety and enjoyment. It contains details of the craft, the equipment supplied or fitted, its systems, and information on its operation and maintenance. Please read it carefully and familiarize yourself with the craft before using it. If this is your first craft, or you are changing to a type of craft you are not familiar with, for your own comfort or safety, please ensure that you obtain handling and operating experience before assuming command of the craft. Your dealer or national sailing federation or yacht club will be pleased to advise you of local sailing schools or competent instructors. PLEASE KEEP THIS MANUAL IN A SECURE PLACE, AND PASS ON TO THE NEW OWNER WHEN YOU SELL THE CRAFT Model_____________________ Hull Number__________________________________ Owner 1. ___________________________ Owner 2. ___________________________ Owner 3. __________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ _________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ _________________________________ ___________________________________ __________________________________ _________________________________ Built By: Corsair Marine, Inc. 150 Reed Court, Chula Vista, CA 91911, U.S.A. CORSAIR MARINE, Inc. Page 1 Copyright © 1997 By Corsair Marine Contents General.............................................. -

Set-Up of Flysky FS-I6 Transmitter(Tx) and FS-Ia6b Receiver(Rx)

Set-up of FlySky FS-i6 Transmitter(Tx) and FS-iA6B Receiver(Rx) for DF65 RC Racing Sailboat (David Flakelar) Background The FlySky FS-i6 system operates under the Digital Proportional Protocol using an Automatic Frequency Hopping Digital System. It is a pulse digital system on carrier frequencies unique to a particular transmitter. You don’t need to know how that works. The manufacturer claims there is no risk of interference from another transmitter. These notes are written to help the beginner set-up the FlySky Tx/Rx system to operate with the DF65. There are also a few tips that have nothing to do with the FlySky system but may be of interest. Feedback would be much appreciated. Why I Bought the FlySky TX/Rx System 1. It appears to be used by most of the fast sailors! 2. The marginal cost is the cost of FS-i6 system less cost saving on buying DF65 without Tx and Rx. At current Hobby Warehouse prices this represents an extra cost of (76.4-(237-179)) which is $18. 3. Minimal risk of interference from other sources. 4. Using its built-in telemetry capability, the condition of both batteries is displayed on Tx monitor. Visual and audible alarms can be set. 5. Expo (exponential) and or proportional control can be used on rudder movements 6. Winch action can be desensitised 7. Using Dual Rate alternate rudder settings can be established. Compatibility The FlySky Tx will only operate with a FlySky Rx of which there are several types. The Turnigy and Park Fly products appear to be FlySky re-badged? Instruction Manual A 27-page Instruction Manual is available from the web. -

Nautical Glossary

NAUTICAL GLOSSARY A (Alfa) I have a diver down; keep well clear at slow speed. Aback. A sail sheeted so that the wind fills the "back" of the sail. Abeam. At right angles to the side of the boat. Aboard. Situated on the boat. Adrift. A boat drifting without being propelled. Aft. At or towards the stern or behind the boat. Aground. A boat whose keel is touching the bottom. Amidships. Towards the center of the boat. Apparent wind. The wind aboard a moving boat Astern. Behind the stern of the boat. Athwartships Across the boat from side to side. B (Bravo) I am taking in, or discharging, or carrying dangerous goods. Backstay. The standing rigging running from the stern to the top of the mast, keeping the mast from falling forward. Back. 1. To Sheet a sail to windward and fill the back of the sail and thus stop the boat or propel it backwards. 2. In the case of the wind - to shift counter clockwise from its previous direction. Bail. To empty the boat of water. Ballast. Weight in the keel of a boat that provides stability. Barometer. An instrument that measures air pressure, an aid to forecasting the weather. Batten. A thin wood or fiberglass slat that slides into a pocket in the leech of a sail, helping to maintain an aerodynamic shape. Beam. The width of a boat at its widest point. Beam reach (Point of sail) Sailing in a direction at approximately 90º to the wind. Bear away. To "fall off" or head away from the wind. -

ORC Speed Guide Explanation

OFFSHORE RACING CONGRESS ORC Speed Guide Explanation 1. INTRODUCTION The ORC Speed Guide is a custom-calculated manual for improving performance for an individual boat. It is intended to augment, not to replace, other books and articles which offer general suggestions for the improvement of sailing performance by providing you with specific performance targets for your boat. This Speed Guide will be of interest to both beginners and more experienced sailors who want to have a deeper understanding of the relationships between speed and factors such as sail selection, wind speed, and wind angle. The speed predictions for the individual boats which are central elements of the Speed Guide are derived in two steps: First, the hull and appendages are measured by use of an electronic device so as to put the hull lines into the computer data bank. The other elements of measurement - the rig and sail dimensions, the flotation and stability data, etc. - are also added to the data bank for this one boat. Second, a series of complex calculations are made to find the boat speeds at which all of the elements of drag come into equilibrium with the drive provided by the sails. This is what constitutes the Velocity Prediction Program, or VPP, which is annually updated and improved by ORC. The utility of these VPP-generated predictions and how they relate to the measured performance on board your boat will greatly depend on the steadiness of the sailing conditions, the abilities of the helmsman and crew, and the accuracy of the instrumentation on board. While you cannot necessarily control the weather, the skills of your team can be improved as well as the calibration of the instruments as described in Appendix C of this Guide. -

Blake Marriner, Sarah Hatsell, Paul Craine – 12/3/2008

Week 8 - Be Careful What You Wish For - Blake Marriner, Sarah Hatsell, Paul Craine – 12/3/2008 Two weeks ago, doing RC duty during the Fall Regatta, I was so envious of everyone sailing, as the wind and waves were the type that I enjoy. I silently wished we might get something similar before the fall season ended. Fast forward to Sunday – wish granted and then some.. With a solid, building breeze from the east, the waves kept building and stacking up during the day, to the point where in race 5, I found myself in a few sets that were more then I was looking for to play in and bailed out, looking for smaller waves to ride. By the end of race 5, I was spent and was headed in regardless if there was another race or not. Amnon Gitelson, the PRO for the day, mercifully sent us in after race 5. My game plan for the day was to focus on boat handling, thinking that my weight would provide an edge upwind. Tim Millhiser had other thoughts though and found the right combo of vang and sheet upwind to provide more then I could handle and had me working harder then I wanted and searching for the right settings myself. I ended up with less vang tension and more sheet ease then I would normally use in that wind strength, which seemed to make the groove wider upwind, and easier to steer around the waves. The times when I cranked on more vang, my pointing ability was compromised and could never generate enough speed thru the water to make up for it. -

NCSC Guidelines for Rigging and Tuning the Thistle

NCSC guidelines for rigging and tuning the Thistle Note: Additional information on safe sailing of Thistles is found in the Course Material and Safety sections of this manual SPRING PREPARATION OF THISTLES……………………………………………………...2 RIGGING THISTLES…………………………………………………………………………...4 THISTLE STOWAGE INFORMATION……………………………………………………….5 PROCEDURE FOR ROLLING SAILS…………………………………………………………6 PUTTING A THISTLE TO BED……………………………………………………….……....7 THISTLE TUNING GUIDE……………………….……………………………………………9 GYBING THE THISTLE IN HEAVY AIR….……………………………………….……….16 Section V - Thistles Page 5.1 Updated 2/6/05 SPRING PREPARATION OF THISTLES Hardware All hardware should be removed in the spring, and at a minimum, desanded and sprayed thoroughly with McLube dry lubricant. It is advisable to take apart all cam cleats, clean the insides, and reassemble (best done at home). Take care to keep track of the ball bearings. If you lose track, here is the count: Medium cleats with three layers (metal) : 11 bearings per level Medium cleats with two layers (plastic): 11 on top, 12 on bottom Small cleats with two layers (plastic): 12 bearings per level Traveler: 42 total bearings Leave the hardware off until after you have finished applying Cetol. Running Rigging Replace all worn halyards, sheets, etc. • The vang is set up for either a 12:1 purchase or 8:1. The rig can get confusing, so ask an expert for proper rigging. • There are at least two cam cleats on each 45-degree brace: Cunningham (closest to the mast) and topping lift. Selected Thistles have additional cleats on the 45 for the twing (Green) or the jib tensioner (Gold Rush). • Traveler lines: be sure they are long enough to reach the rails easily: otherwise the middle crew will have to lean into the boat to adjust them – which is exactly what you don’t want in a strong breeze.