Seanchas - an Inportant Irish Tradition Related to Memory, History and Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2003 Archipelago

archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 7, No. 3 Fall 2003 AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC An Exhibiton : Twenty-two Irish and Scottish Gaelic Poems, Translations and Artworks, with Essays and Recitations Fiction: PATRICIA SARRAFIAN WARD “Alaine played soccer with the refugees, she traded bullets and shrapnel around the neighborhood . .” from THE BULLET COLLECTION Poem: ELEANOR ROSS TAYLOR Our Lives Are Rounded With A Sleep Reflection: ANANT KUMAR The Mosques on the Banks of the Ganges: Apart or Together? tr. from the German by Rajendra Prasad Jain Photojournalism: PETER TURNLEY Seeing Another War in Iraq in 2003 and The Unseen Gulf War : Photographs Audio report on-line by Peter Turnley Endnotes: KATHERINE McNAMARA The Only God Is the God of War : On BLOOD MERIDIAN, an American myth printed from our pdf edition archipelago www.archipelago.org CONTENTS AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC 4 Introduction : Malcolm Maclean 5 On Contemporary Irish Poetry : Theo Dorgan 9 Is Scith Mo Chrob Ón Scríbainn ‘My hand is weary with writing’ 13 Claochló / Transfigured 15 Bean Dubh a’ Caoidh a Fir Chaidh a Mharbhadh / A Black Woman Mourns Her Husband Killed by the Police 17 M’anam do sgar riomsa a-raoir / On the Death of His Wife 21 Bean Torrach, fa Tuar Broide / A Child Born in Prison 25 An Tuagh / The Axe 30 Dan do Scátach / A Poem to Scátach 34 Èistibh a Luchd An Tighe-Se / Listen People Of This House 38 Maireann an t-Seanmhuintir / The Old Live On 40 Na thàinig anns a’ churach -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

Barristers on Panel

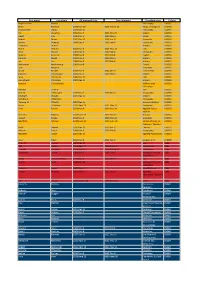

st Report Run Date: 21 Jun 2019 BARRISTERS ON PANEL The below list contains information on the number of payments* and the total amount paid to On Panel barristers for the period 1/07/18 – 31/12/18 Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments Buckley, Declan 417,945 52 McGrath, Imogen 43,604 15 Binchy, Michael 11,132 8 Fitzpatrick, Andrew 3,094 6 Egan, Emily 394,952 24 Boughton, David 43,480 86 Farrelly, Aoife 10,908 13 Fitzgerald, William 2,653 11 Hanratty, Patrick 385,932 11 Fleck, Kieran 43,142 7 Delaney, Michael Patrick 10,701 2 MacMahon, Noel A. 2,583 1 Halpin, Conor 337,833 26 Gayer, Sasha Louise 39,452 4 Lydon, Eileen 10,578 2 Roberts, Conor 2,030 3 O'Braonain, Luan 231,215 17 Ramsey, Michael 37,023 1 Hand, Derry 10,376 8 Cheatle, John 1,845 1 Kavanagh, James M. 187,198 6 Fahey, Grainne 36,678 73 Scully, Lorraine 9,696 6 Maher, Jeremy 1,538 2 Foley, Brian 181,914 20 McGuinness, Donal 29,223 5 Hogan, John 9,545 7 Keleher, Daniel 1,162 1 Woulfe, Donnchadh 179,160 9 Lowe, Robert 28,226 2 Walsh, Aidan 8,979 1 Hewson, Dermot G. 1,119 1 McCrann, Oonah 159,623 18 Barrington, Eileen 27,596 2 Kilfeather, Jonathan 8,642 4 Keane, Deirdre 1,076 4 McCullough, Eoin 143,268 14 White, Rory 27,032 14 Fleming, David 8,107 2 Danaher, Gerard 954 2 Corcoran, Sarah 139,707 104 Farren, Georgina 25,227 5 Tennyson, Lauren 7,679 3 Cullinane, Padraig J. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

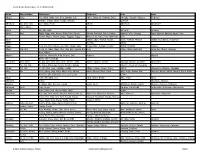

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/Area

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/area College Roger Garrett Barden Philosophy CACSSS Brian Bocking 2015 Nov 15 2016 March 14 Study of Religions CACSSS Desmond M Clarke 2007 Dec 11 Philosophy CACSSS Pat Coughlan 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 English CACSSS David Cox 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Music CACSSS Robert Devoy 2011 Dec 13 2012 Jan 11 Geograhy CACSSS Francis Douglas 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Thomas J Dunne History CACSSS Maire Herbert 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 Irish CACSSS Aine Hyland 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Colbert Kearney 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 English CACSSS Dermot Keogh 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 History CACSSS Joe Lee 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 History CACSSS Mathew M MacNamara 2005 Nov 8 French CACSSS John Maguire Sociology CACSSS Grace Neville 2012 Nov 6 2012 Dec 6 French/T&L CACSSS Eamonn O Carragain 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 English CACSSS Sean O Coileain 2006 Dec 12 Irish CACSSS Donnchadh O Corrain 2007 Dec 11 History CACSSS Gearóid Ó Crualaoich Folklore and CACSSS Ethnology Padraig O Riain irish CACSSS Patrick O'Flanagan 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Geography CACSSS Elisabeth Okasha 2007 Dec 11 English CACSSS Brendan E O'Mahony Philosophy CACSSS Terence W O'Reilly 2007 Dec 11 Hispanic Studies CACSSS Denis O'Sullivan 2011 April 19 2011 May 11 Education CACSSS Fred Powell 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Applied Social CACSSS Studies Geoffrey Roberts 2017 June 13 2017 Dec 01 History CACSSS Joseph Ruane 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Sociology CACSSS Manfred Schewe 2019 June 11 2019 June 18 School of Lang, Lit, CACSSS -

Interactive Multilinear Narratives and Real-Life Community Stories

Crossings - Volume 4, Issue 1 - Nisi et al. 09/29/2006 02:27 PM Crossings: eJournal of Art and raison d'être contribute gallery issues : 1.1 : 1.2 : 2.1 : 3.1 : 4.1 Technology Weird View: Interactive Multilinear Narratives and Real-Life Community Stories Valentina Nisi Story Networks Group Media Lab Europe Ireland Mads Haahr Department of Computer Science Trinity College, Dublin Ireland Abstract. This paper presents our experiences with Weird View, a multi-branching interactive narrative, harnessing the power of hyperlinked structures and oral storytelling. True stories were collected by word of mouth from inhabitants of a terrace of houses in Dublin, Ireland, and supplemented with video and photography to form a collection of narrative fragments. A computer application was built to allow the narratives to be navigated. In this way, Weird View attempts to capture part of the community folklore and re- present it to the community in the form of an interactive, nonlinear narrative. The viewer is presented with the fact that a community exists and is continually formed, around place, time, life conditions and social networks. When shown to the community, the Weird View project resulted in awakening community awareness through reappropriation of local, social and personal stories. Introduction A common use of information technologies is to make spatial separation of individuals irrelevant and thereby allow the formation of communities across geographical boundaries. Such online communities, made possible through the increased adoption of information and communication technologies, have received a significant amount of attention. However, the same technologies can also be used to reinforce more traditional types of communities, often based in shared spatial and cultural contexts. -

61574447.Pdf

Title Towards a regional understanding of Irish traditional music Author(s) Kearney, David Publication date 2009-09 Original citation Kearney, D. 2009. Towards a regional understanding of Irish traditional music. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b1985733~S0 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2009, David Kearney http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/977 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:09:41Z Towards a regional understanding of Irish traditional music David Kearney, B.A., H.Dip. Ed. Thesis presented for the award of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) National University of Ireland, Cork Supervisors: Professor Patrick O’Flanagan, Department of Geography Mel Mercier, Department of Music September 2009 Submitted to National University of Ireland, Cork 1 Abstract The geography of Irish traditional music is a complex, popular and largely unexplored element of the narrative of the tradition. Geographical concepts such as the region are recurrent in the discourse of Irish traditional music but regions and their processes are, for the most part, blurred or misunderstood. This thesis explores the geographical approach to the study of Irish traditional music focusing on the concept of the region and, in particular, the role of memory in the construction and diffusion of regional identities. This is a tripartite study considering people, place and music. Each of these elements impacts on our experience of the other. All societies have created music. Music is often associated with or derived from places. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

Ancient Greek Tragedy and Irish Epic in Modern Irish

MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Katherine Anne Hennessey, B.A., M.A. ____________________________ Dr. Susan Cannon Harris, Director Graduate Program in English Notre Dame, Indiana March 2008 MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE Abstract by Katherine Anne Hennessey Over the course of the 20th century, Irish playwrights penned scores of adaptations of Greek tragedy and Irish epic, and this theatrical phenomenon continues to flourish in the 21st century. My dissertation examines the performance history of such adaptations at Dublin’s two flagship theatres: the Abbey, founded in 1904 by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, and the Gate, established in 1928 by Micheál Mac Liammóir and Hilton Edwards. I argue that the potent rivalry between these two theatres is most acutely manifest in their production of these plays, and that in fact these adaptations of ancient literature constitute a “disputed territory” upon which each theatre stakes a claim of artistic and aesthetic preeminence. Partially because of its long-standing claim to the title of Ireland’s “National Theatre,” the Abbey has been the subject of the preponderance of scholarly criticism about the history of Irish theatre, while the Gate has received comparatively scarce academic attention. I contend, however, that the history of the Abbey--and of modern Irish theatre as a whole--cannot be properly understood except in relation to the strikingly different aesthetics practiced at the Gate. -

1 FIONN in HELL an Anonymous Early Sixteenth-Century Poem In

1 FIONN IN HELL An anonymous early sixteenth-century poem in Scots describes Fionn mac Cumhaill as having ‘dang þe devill and gart him ʒowle’ (‘struck the Devil and made him yowl’) (Fisher 1999: 36). The poem is known as ‘The Crying of Ane Play.’ Scots literature of the late medieval and early modern period often shows a garbled knowledge of Highland culture; commonly portraying Gaels and their language and traditions negatively. Martin MacGregor notes that Lowland satire of Highlanders can, ‘presuppose some degree of understanding of the language, and of attendant cultural and social practices’ (MacGregor 2007: 32). Indeed Fionn and his band of warriors, 1 collectively Na Fiantaichean or An Fhèinn0F in modern Scottish Gaelic, are mentioned a number of times in Lowland literature of the period (MacKillop 1986: 72-74). This article seeks to investigate the fate of Fionn’s soul in late medieval and early modern Gaelic literature, both Irish and Scottish. This is done only in part to consider if the yowling Devil and his encounter with Fionn from the ‘The Crying of Ane Play’ might represent something recognizable from contemporaneous Gaelic literature. Our yowling Devil acts here as something of a prompt for an investigation of Fionn’s potential salvation or damnation in a number of sixteenth-century, and earlier, Gaelic ballads. The monumental late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century (Dooley 2004) text Acallam na 2 Senórach (‘The Colloquy of the Ancients’) will also be considered here.1F Firstly, the Scots poem must be briefly investigated in order to determine its understanding of Gaelic conventions. -

Ansteorran College of Heralds Does Estrill Swet, Retiarius Pursuivant, Make Greetings

Here are the decisions about ILoI0009 made on December 9, 2000 (AS XXXV) at Stargate Yule Revel, as typed by Kathri (who has corrected the item headers where Bordure needed it, which explains why some of the comments seem to be about problems that don't exist.) Griffon, Bordure (and deputy-Asterisk-for-the-day) Unto the Ansteorran College of Heralds does Estrill Swet, Retiarius Pursuivant, make greetings. For information on commentary submission formats or to receive a copy of the collated commentary, you can contact me at: Deborah Sweet 824 E 8th, Stillwater, OK 74074 405/624-9344 (before 10pm) [email protected] Commenters for this issue: Magnus von Lübeck - Raven's Fort. All items were checked against the on-line O&A. Mari Elspeth nic Bryan - Solveig Throndardottir, Name Construction in Mediaeval Japan, Free Trumpet Studies in Heraldry & Onomastics 87 (Albuquerque, NM: The Outlaw Press, 1994). Andrew W. Nelson, The Compact Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary, abridged by John H. Haig. (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1999). The documentation for a number of the name submissions in this ILoI is not presented in enough detail to be reviewed by the College of Arms without problems. It is not simply enough to (for example) state that a name is in Withycombe. Even "Withycombe, page (page #)" is not enough. Different editions of Withycombe have the headers on different pages. Even the 3rd edition hardback has entries on different pages than the 3rd edition paperback. Name documentation has to be summarized clearly and completely enough that: 1) a commenter can quickly and easily look up the reference and 2) it is clear why this reference supports the registration of the submitted name In a number of the comments below, I refer to the Annals of Connacht. -

Sacred Space. a Study of the Mass Rocks of the Diocese of Cork and Ross, County Cork

Sacred Space. A Study of the Mass Rocks of the Diocese of Cork and Ross, County Cork. Bishop, H.J. PhD Irish Studies 2013 - 2 - Acknowledgements My thanks to the University of Liverpool and, in particular, the Institute of Irish Studies for their support for this thesis and the funding which made this research possible. In particular, I would like to extend my thanks to my Primary Supervisor, Professor Marianne Elliott, for her immeasurable support, encouragement and guidance and to Dr Karyn Morrissey, Department of Geography, in her role as Second Supervisor. Her guidance and suggestions with regards to the overall framework and structure of the thesis have been invaluable. Particular thanks also to Dr Patrick Nugent who was my original supervisor. He has remained a friend and mentor and I am eternally grateful to him for the continuing enthusiasm he has shown towards my research. I am grateful to the British Association for Irish Studies who awarded a research scholarship to assist with research expenses. In addition, I would like to thank my Programme Leader at Liverpool John Moores University, Alistair Beere, who provided both research and financial support to ensure the timely completion of my thesis. My special thanks to Rev. Dr Tom Deenihan, Diocesan Secretary, for providing an invaluable letter of introduction in support of my research and to the many staff in parishes across the diocese for their help. I am also indebted to the people of Cork for their help, hospitality and time, all of which was given so freely and willingly. Particular thanks to Joe Creedon of Inchigeelagh and local archaeologist Tony Miller.