Sacred Space. a Study of the Mass Rocks of the Diocese of Cork and Ross, County Cork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermarriage and Other Families This Page Shows the Interconnection

Intermarriage and Other Families This page shows the interconnection between the Townsend/Townshend family and some of the thirty-five families with whom there were several marriages between 1700 and 1900. It also gives a brief historical background about those families. Names shown in italics indicate that the family shown is connected with the Townsend/Townshend elsewhere. Baldwin The Baldwin family in Co Cork traces its origins to William Baldwin who was a ranger in the royal forests in Shropshire. He married Elinor, daughter of Sir Edward Herbert of Powys and went to Ireland in the late 16th century. His two sons settled in the Bandon area; the eldest brother, Walter, acquired land at Curravordy (Mount Pleasant) and Garrancoonig (Mossgrove) and the youngest, Thomas, purchased land at Lisnagat (Lissarda) adjacent to Curravordy. Walter’s son, also called Walter, was a Cromwellian soldier and it is through his son Herbert that the Baldwin family in Co Cork derives. Colonel Richard Townesend [100] Herbert Baldwin b. 1618 d. 1692 of Curravordy Hildegardis Hyde m. 1670 d. 1696 Mary Kingston Marie Newce Horatio Townsend [104] Colonel Bryan Townsend [200] Henry Baldwin Elizabeth Becher m. b. 1648 d. 1726 of Mossgrove 1697 Mary Synge m. 13 May 1682 b. 1666 d. 1750 Philip French = Penelope Townsend [119] Joanna Field m. 1695 m. 1713 b. 1697 Elizabeth French = William Baldwin John Townsend [300] Samuel Townsend [400] Henry Baldwin m. 1734 of Mossgrove b. 1691 d. 1756 b.1692 d. 1759 of Curravordy b.1701 d. 1743 Katherine Barry Dorothea Mansel m. 1725 b. 1701 d. -

15Th September

7 NIGHTS IN LISBON INCLUDINGWIN! FLIGHTS 2019 6th - 15th September www.atasteofwestcork.com Best Wild Atlantic Way Tourism Experience 2019 – Irish Tourism & Travel Industry Awards 1 Seaview House Hotel & Bath House Seaview House Hotel & Bath House Ballylickey, Bantry. Tel 027 50073 Join us for Dinner served nightly or Sunday [email protected] House in Hotel our Restaurant. & Bath House Perfect for Beara & Sheep’s Head walkingAfternoon or aHigh trip Tea to theor AfternoonIslands Sea served on Saturday by reservation. September 26th – 29th 2019 4 Star Country Manor House Enjoy an Organic Seaweed Hotel, set in mature gardens. Enjoy an Organic Seaweed Bath in one IARLA Ó LIONÁIRD, ANTHONY KEARNS, ELEANOR of Bathour Bath in one Suites, of our or Bath a Treatment Suites, in the Highly acclaimed by ornewly a Treatment developed in the Bath newly House. SHANLEY, THE LOST BROTHERS, YE VAGABONDS, Michelin & Good Hotel developed Bath House with hand Guides as one of Ireland’s top 4**** Manor House Hotel- Ideal for Small Intimate Weddings, JACK O’ROURKE, THOMAS MCCARTHY. craftedSpecial woodburning Events, Private Dining outdoor and Afternoon Tea. destinations to stay and dine saunaSet within and four ac rhotes of beaut tub;iful lya manicu perfectred and mature gardens set 4**** Manor House Hotel- Ideal for Small Intimate Weddings, back from the Sea. Seaview House Hotel is West Cork’s finest multi & 100 best in Ireland. recoverySpecial followingEvents, Private Diningactivities and Afternoon such Tea. award winning Country Manor Escape. This is a perfect location for discovering some of the worlds most spectacular scenery along the Wild ****************** Set withinas four walking acres of beaut andifully manicu cycling.red and mature gardens set Atlantic Way. -

Diocese : Cork and Ross

Diocese of CORK AND ROSS Parish Register Dates Film No. Abbeymahon see Lislea ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Aglish see Ovens ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Ardfield and Rathbarry Baptisms Jan. 1, 1801 - Apr. 5, 1837 P.4771 (Jan. 1802 - Jan. 1803 wanting) Marriages May 1800 - July 2, 1837 (1812 - 1816 wanting) Rathbarry and Ardfield Baptisms Apr. 7, 1832 - Dec. 27, 1876 Marriages May 17, 1832 - May 30, 1880 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Ardnageeha see Watergrasshill ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Athnowen see Ovens ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Aughadown Baptisms June, 1822 - Oct. 12, 1838 P.4775 (Very illegible) Oct. 20, 1838 - Jan. 28, 1865 Jan. 1, 1865 - Dec. 31, 1880 Marriages Oct. 15, 1822 - Feb. 28, 1865 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Ballinadee see Ringrone ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Ballincollig and Ballinore Baptisms Jan. 16, 1820 - Mar. 19, 1828 P.4791 Marriages Jan. 12, 1825 - Feb. 19, 1828 Baptisms Aug. 26, 1828 - Dec. 20, 1857 Marriages Aug. 28, 1828 - Nov. 28, 1857 Baptisms Jan. 3, 1858 - Dec. 24, 1880 Marriages Oct. 25, 1873 - Aug. 29, 1880 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Issue 91, Oct 1999

\ ~t>onsors Of che lRlsh ornencecc Compass Point ,,~ ," J, No.91 October .. November 1999 , REI.SO t.uJII.,.'li ...'!~:i ,J·l· ilS dl~ till', J', 17 \ hil l. (..1.1'''' (,tlt!(." ;)~lII' ( "lllj>"S' f'el III \. \ \ , )( ., ,II'" n,-' ':t,i t'- ,'~d"'\rt io' f'\11{' \illl\I ~'. ,...~\P" \\llIt I "Ii \ \ , (1Inll,t ...·, • • • • I' Itll!" .,1.1' 111"'" .. '.,h !,"-hOi'- t~ . CQMPIQ5~·l-\ • ,\I.,' 1 ~r"'1" I U!t Ih'.'~') f; '",.h -III ''':1 \.\ J-\1 ~.'h.,'· 11 "jI_"')f""1111~ 'tLh 'flit "ll'Ir"lIt~" !\.III,d.i. lIJ1:~ I 'Ju') h'" 1""111 tum .I·!:~~'\_ n"lWI,f It., '1!J! "II'I! 1"11{ IU vi 1',7i u N til 1'",,1-1) ...,.,. O' If ,.!.r rl,~;h ·H,"'I ...bl~~(\1 III \.il(IP ..,1 I h( ..... ,~ ~'l Lit.' ,llId Hit lI$h· I~·'.-II(JIr!Pf ...d\:" I 10 Market Square. Lvtham.Lancs FY8 5lW Tel: ()'1253 7!l5.'i97 Fax: 0 I'J53 i3<)4bO email: ri('kq,(,Of1lPil~~p...int.dernun.ru.uk ~ 1111)1'111(>1 & 111\ ()"'flhu'lil '" "ILVA olll'"II"""'\': "'Illlfl"lt'n' ~~~~~~~~~g~~~g The Irish Orienteer is available McOcOMN":lriNMoioicnoio (.J(,J~uUr')c.JWO_N(".INN from all Irish orienreering clubs t- W woIIOl/)wW w~ or by direer subscriprion from che IRISh oraenccec z8~o Io"1N EU) ci. ~W- UI/)~W ~cr E CD the Editor: John McCullougll, 9 No.9' October - November '999 UJ >' I-MW O-WI (I) -0 ~U)~U) a:<w a:a:l-u8~ <,.... Arran Road, Dublin 9 Q) 0..0 a:C)~3 j:;:~a: (I) Now What? - cr' w<cr": IUO (I) O.)t. -

BMH.WS1234.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,234 Witness Jack Hennessy, Knockaneady Cottage, Ballineen, Co. Cork. Identity. Adjutant Ballineen Company Irish Vol's. Co. Cork; Section Leader Brigade Column. Subject. Irish Volunteers, Ballineen, Co. Cork, 1917-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2532 Form BSM2 STATEMENT BY JOHN HENNESSY, Ballineen, Co. Cork. I joined the Irish Volunteers at Kilmurry under Company Captain Patrick O'Leary in 1917. I remained with that company until 1918 when I moved to Ballineen, where I joined the local company under Company Captain Timothy Francis. Warren. Shortly after joining the company I was appointed Company Adjutant. During 1918 and the early days of 1919 the company was. being trained and in 1918 we had preparations made. to resist conscription. I attended meetings of the Battalion Council (Dunmanway Battalion) along with the Company Captain. The Battalion Council discussed the organisation and training in each company area. In May, 1919, the Ballineen Company destroyed Kenniegh R.I.C. barracks. which had been vacated by the garrison.. Orders were issued by the brigade through each battalion that the local R.I.C. garrison was to be boycotted by all persons in the area. This order applied to traders, who were requested to stop supplying the R.I.C. All the traders obeyed the order, with the exception of one firm, Alfred Cotters, Ballineen, who continued to supply the R.I.C. with bread. The whole family were anti-Irish and the R.I.C. -

Scealta Scoile!

Scealta Scoile! Meitheamh 2015 It’s Summertime! School’s Out! Marymount Hospice Our rang a sé pupils gave us yet another reason to be proud by making a wonderful Confirmation commitment to improving the gardens around nearby Marymount Hospice. Gardening gloves, buckets, forks and hoes were to be seen in action on Friday mornings during the final term, in what is a heart-warming example of how young people can be a force for such good. Aside from the spectacular transformation of the beds and planted areas around Marymount, not to mention the addition of hundreds of euros worth of beautiful flowers, paid for by a cake-sale organised by the pupils, their lively presence around the facility was welcomed and enjoyed immensely by the community there. Sincere thanks to our trusty band of rang a sé parents who did so much to facilitate this work. Is álainn agus is iontach an saothar a deintear i Marymount. New Infants Induction Day / Ár Naonáin Nua The school welcomed in glimpse of “big school” while excess of forty incoming parents enjoyed a welcome junior infants to an “cupán tae” in the Scout induction afternoon recently. Den, courtesy of our PA. Ms. Cullen & Ms. Hourihan Céad fáilte romhaibh go gave their new recruits a very Scoil Bhailenóra, a pháistí warm Ballinora welcome agus a thuistí! and gave the children a Scoil Bhailenóra, Waterfall, Cork. Keep up to date with all the latest news and Tel: 021-4871664 information on our school website. E-Mail: [email protected] Ballinorans.ie or scan the QR code using a Twitter: @SBNORA smart phone. -

The Wesleyan Enlightenment

The Wesleyan Enlightenment: Closing the gap between heart religion and reason in Eighteenth Century England by Timothy Wayne Holgerson B.M.E., Oral Roberts University, 1984 M.M.E., Wichita State University, 1986 M.A., Asbury Theological Seminary, 1999 M.A., Kansas State University, 2011 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2017 Abstract John Wesley (1703-1791) was an Anglican priest who became the leader of Wesleyan Methodism, a renewal movement within the Church of England that began in the late 1730s. Although Wesley was not isolated from his enlightened age, historians of the Enlightenment and theologians of John Wesley have only recently begun to consider Wesley in the historical context of the Enlightenment. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between a man, John Wesley, and an intellectual movement, the Enlightenment. As a comparative history, this study will analyze the juxtaposition of two historiographies, Wesley studies and Enlightenment studies. Surprisingly, Wesley scholars did not study John Wesley as an important theologian until the mid-1960s. Moreover, because social historians in the 1970s began to explore the unique ways people experienced the Enlightenment in different local, regional and national contexts, the plausibility of an English Enlightenment emerged for the first time in the early 1980s. As a result, in the late 1980s, scholars began to integrate the study of John Wesley and the Enlightenment. In other words, historians and theologians began to consider Wesley as a serious thinker in the context of an English Enlightenment that was not hostile to Christianity. -

Sea Environmental Report the Three

SEA ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT FOR THE THREE PENINSULAS WEST CORK AND KERRY DRAFT VISITOR EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT PLAN for: Fáilte Ireland 88-95 Amiens Street Dublin 1 by: CAAS Ltd. 1st Floor 24-26 Ormond Quay Upper Dublin 7 AUGUST 2020 SEA Environmental Report for The Three Peninsulas West Cork and Kerry Draft Visitor Experience Development Plan Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................v Glossary ..................................................................................................................vii SEA Introduction and Background ..................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Terms of Reference ........................................................................... 1 1.2 SEA Definition ............................................................................................................ 1 1.3 SEA Directive and its transposition into Irish Law .......................................................... 1 1.4 Implications for the Plan ............................................................................................. 1 The Draft Plan .................................................................................... 3 2.1 Overview ................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Relationship with other relevant Plans and Programmes ................................................ 4 SEA Methodology .............................................................................. -

Audit Maritime Collections 2006 709Kb

AN THE CHOMHAIRLE HERITAGE OIDHREACHTA COUNCIL A UDIT OF M ARITIME C OLLECTIONS A Report for the Heritage Council By Darina Tully All rights reserved. Published by the Heritage Council October 2006 Photographs courtesy of The National Maritime Museum, Dunlaoghaire Darina Tully ISSN 1393 – 6808 The Heritage Council of Ireland Series ISBN: 1 901137 89 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Objective 4 1.2 Scope 4 1.3 Extent 4 1.4 Methodology 4 1.5 Area covered by the audit 5 2. COLLECTIONS 6 Table 1: Breakdown of collections by county 6 Table 2: Type of repository 6 Table 3: Breakdown of collections by repository type 7 Table 4: Categories of interest / activity 7 Table 5: Breakdown of collections by category 8 Table 6: Types of artefact 9 Table 7: Breakdown of collections by type of artefact 9 3. LEGISLATION ISSUES 10 4. RECOMMENDATIONS 10 4.1 A maritime museum 10 4.2 Storage for historical boats and traditional craft 11 4.3 A register of traditional boat builders 11 4.4 A shipwreck interpretative centre 11 4.5 Record of vernacular craft 11 4.6 Historic boat register 12 4.7 Floating exhibitions 12 5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 12 5.1 Sources for further consultation 12 6. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF RECORDED COLLECTIONS 13 7. MARITIME AUDIT – ALL ENTRIES 18 1. INTRODUCTION This Audit of Maritime Collections was commissioned by The Heritage Council in July 2005 with the aim of assisting the conservation of Ireland’s boating heritage in both the maritime and inland waterway communities. 1.1 Objective The objective of the audit was to ascertain the following: -

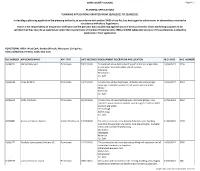

Report Weekly Lists Invalid Applications

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS INVALID APPLICATIONS FROM 28/03/2020 TO 03/04/2020 that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE INVALID DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION 20/00153 Ann and Ian Yellowlees Permission 30/03/2020 (i) Change of plan of extension to dwelling house previously approved under planning reference 19/00093, (ii) fenestration changes to dwelling, (iii) installation of new carport and open veranda and (iv) all associated site works Bocarnagh Glengarriff Co. Cork 20/00160 Robbie Ahern Permission 30/03/2020 The construction of dwelling house (change of design to that permitted under Planning Reg. No. 19/552) and all associated site works Camus Clonakilty Co. Cork 20/00168 Michael & Thomas Allen Permission for 30/03/2020 Retention of change of use of 2nd floor area to a 2 bedroom Retention apartment with external roof lights. Derrigra Enniskeane Co. Cork 20/04483 Pat and Mairead Donnelly Permission for 02/04/2020 Permission to retain variations to dwelling house which was Retention constructied under planning ref 503/75 Windsor Ovens Co. Cork 20/04486 Louise O'Mahony Permission for 30/03/2020 Permission to retain (I) alterations to rear elevation and (ii) Retention balcony to rear of existing dwelling. -

(2010) Records from the Irish Whale

INJ 31 (1) inside pages 10-12-10 proofs_Layout 1 10/12/2010 18:32 Page 50 Notes and Records Cetacean Notes species were reported with four sperm whales, two northern bottlenose whales, six Mesoplodon species, including a True’s beaked whale and two Records from the Irish Whale and pygmy sperm whales. This year saw the highest number of Sowerby’s beaked whales recorded Dolphin Group for 2009 stranded in a single year. Records of stranded pilot whales were down on previous years. Compilers: Mick O’Connell and Simon Berrow A total of 23 live stranding events was Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, recorded during this period, up from 17 in 2008 Merchants Quay, Kilrush, Co. Clare and closer to the 28 reported in 2007 by O’Connell and Berrow (2008). There were All records below have been submitted with however more individuals live stranded (53) adequate documentation and/or photographs to compared to previous years due to a two mass put identification beyond doubt. The length is a strandings involving pilot whales and bottlenose linear measurement from the tip of the beak to dolphins. Thirteen bottlenose dolphin strandings the fork in the tail fin. is a high number and it includes four live During 2009 we received 136 stranding stranding records. records (168 individuals) compared to 134 records (139 individuals) received in 2008 and Fin whale ( Balaenoptera physalus (L. 1758)) 144 records (149 individuals) in 2007. The Female. 19.7 m. Courtmacsherry, Co. Cork number of stranding records reported to the (W510429), 15 January 2009. Norman IWDG each year has reached somewhat of a Keane, Padraig Whooley, Courtmacsherry plateau (Fig. -

Report Weekly Lists Planning Applications Granted

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 19/06/2021 TO 25/06/2021 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Macroom, Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION M.O. DATE M.O. NUMBER 20/06555 Michael Hourigan Permission 18/11/2020 To construct a two storey dwelling with entrance, proprietary 24/06/2021 5156 waste water treatment plant and all services Demesne Newmarket Co. Cork 20/06608 Chloe Kelleher Permission 23/11/2020 Construction of dwelling house, detached domestic garage, 25/06/2021 5169 sewerage treatment system and all associated site works. Glinny Riverstick Co. Cork 20/06638 Cathy O'Sullivan Permission 25/11/2020 Construction of new dwellinghouse, domestic garage, new 23/06/2021 5143 entrance, waste water treatment system together with all other ancillary site works. Gortnaclogh Ballinhassig Co. Cork 20/06880 Aaron and Marina Durnin Outline Permission 17/12/2020 The construction of a new detached dormer scale dwelling 21/06/2021 5109 including all associated site works, new site entrance, drainage works and associated landscaping.