Railways in Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indiana Medical History Quarterly

INDIANA MEDICAL HISTORY QUARTERLY INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Volume IX, Number 1 March, 1983 R131 A1 15 V9 NOI 001 The Indiana Medical History Quarterly is published by the Medical History Section of the Indiana Historical Society, 315 West Ohio Street, Indianapolis Indiana 46202. EDITORIAL STAFF CHARLES A. BONSETT, M.D., Editor 6133 East 54th Place Indianapolis, Indiana 46226 ANN G. CARMICHAEL, M.D., Ph.D., Asst. Editor 130 Goodbody Hall Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana 47401 KATHERINE MANDUSIC MCDONELL, M.A., Managing Editor Indiana Historical Society 315 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 MEDICAL HISTORY SECTION COMMITTEE CHARLES A. BONSETT, M.D., Chairman JOHN U. KEATING, M.D. KENNETH G. KOHLSTAEDT, M.D. BERNARD ROSENAK, M.D. DWIGHT SCHUSTER, M.D. WILLIAM M. SHOLTY, M.D. W. D. SNIVELY, JR., M.D. MRS. DONALD J. WHITE Manuscripts for publication in the Quarterly should be submitted to Katherine McDonell, Indiana Medical History Section, Indiana Historical Society, 315 West Ohio Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202. All manuscripts (including footnotes) should be typewritten, double-spaced, with wide margins and footnotes at the end. Physicians’ diaries, casebooks and letters, along with nineteenth century medical books and photographs relating to the practice of medicine in Indiana, are sought for the Indiana Historical Society Library. Please contact Robert K. O’Neill, Director, In diana Historical Society Library, 315 West Ohio Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202. The Indiana Medical History Museum is interested in nineteenth century medical ar tifacts for its collection. If you would like to donate any of these objects to the Museum, please write to Dr. Charles A. -

Cancel Culture: Posthuman Hauntologies in Digital Rhetoric and the Latent Values of Virtual Community Networks

CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks Heather Palmer Rik Hunter Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Matthew Guy Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 By Austin Michael Hooks All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This study explores how modern epideictic practices enact latent community values by analyzing modern call-out culture, a form of public shaming that aims to hold individuals responsible for perceived politically incorrect behavior via social media, and cancel culture, a boycott of such behavior and a variant of call-out culture. As a result, this thesis is mainly concerned with the capacity of words, iterated within the archive of social media, to haunt us— both culturally and informatically. Through hauntology, this study hopes to understand a modern discourse community that is bound by an epideictic framework that specializes in the deconstruction of the individual’s ethos via the constant demonization and incitement of past, current, and possible social media expressions. The primary goal of this study is to understand how these practices function within a capitalistic framework and mirror the performativity of capital by reducing affective human interactions to that of a transaction. -

Mapa Del Cantón Santa Ana 09, Distrito 01 a 06

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 1 SAN JOSÉ CANTÓN 09 SANTA ANA 473200 475200 477200 479200 481200 483200 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos Belén Tajo por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 1 San José 1 09 03 U12 Heredia l a Monte Roca 1102400 n 1102400 a C Cantón 09 Santa Ana Almacenes Meco - Plantel Santa Ana Viñedo A Soda Hacienda Herrera B e Cond. Q l é n Cond. Los Sauces Cond. Residencias Los Olivos 1 09 03 U13/U14 Cond. Vista del Roble 1 09 03 U31 Honduras A G ua Ministerio de Hacienda Ebais ch ipe 1 09 03 U32 lín Cond. Corinto Cond. Alcázares Parque Comercial Lindora 1 09 03 U15 Cond. El Pueblo Órgano de Normalización Técnica Ofersa Vindi BlueFlame 1 09 03 U16/U17 e r 1 09 03 U33 b Cond. Altos de Pereira Gasolinera Uno m Hultec o N Puertas del Sol Radial San Antonio in S ombre Cond. Lago Mar Alajuela Planta Tratamiento Lagos de Lindora Sin N Residencial Lago Mar San José Colonia Bella Vista Lindora Park 1 09 03 R26 1 09 03 U27 1 09 03 R04 Servidumbre Eléctrica CTP de Santa Ana Urb. Quirós Centro Educativo Lagos de Lindora 1 09 03 U01/U02 a l Fundación GAD l Hotel Aloft Parque i Q r Iglesia Católica i u e Oracle V Lindora æ b o r í a Forum II d Residencial Valle Verde R Cond. Verdi a BCR P Casas Vita o z 1 09 03 U35 S Cerro Palomas ó 1 09 03 U34 in n Barrio Los Rodríguez N C 1 09 03 U11 om a 1 09 03 U44 b n Banco Lafise ez re al Quebrada Rodrigu ilas 1 09 03 U25 a P Cond. -

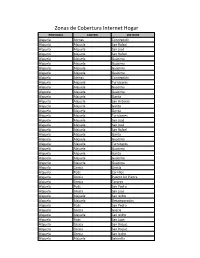

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Para Ver Libro Clic Aquí

JESÚSEL HOMBRE, EL T.POLÍ T PIÑEROICO, EL GOBERNADOR JESÚSEL HOMBRE, EL T.POLÍ T PIÑEROICO, EL GOBERNADOR Héctor Luis Acevedo Editor 2005 Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducida, almacenada o trasmitida en manera alguna, sin permiso de la Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico © Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico Recinto Metropolitano PO Box 191293 San Juan, Puerto Rico, 00919-1293 Héctor Luis Acevedo, editor Fotografías cortesía de: Familia Piñero Fundación Luis Muñoz Marín Archivo General de Puerto Rico Biblioteca de la Universidad de Puerto Rico Biblioteca del Tribunal Supremo de Puerto Rico Biblioteca Presidencial Harry S. Truman Diagramación y diseño: Taller de Ediciones Puerto Edición al cuidado de: José Carvajal ISBN 1-933352-27-2 Impreso en Colombia Printed in Colombia Índice Colaboradores ................................................................................................................ 99 Mensaje del Presidente ................................................................................................... 13 Mensaje de la Rectora .................................................................................................... 1515 Presentación de la Obra ................................................................................................. 1717 A Manera de Prólogo - Historia de un Nombramiento que Cambió la Historia por Héctor Luis Acevedo, Editor ..................................................... 23 I Testimonios y ensayos de sus familiares Recuerdos de la Infancia -

15-108 Puerto Rico V. Sanchez Valle (06/09/2016)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2015 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus COMMONWEALTH OF PUERTO RICO v. SANCHEZ VALLE ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF PUERTO RICO No. 15–108. Argued January 13, 2016—Decided June 9, 2016 Respondents Luis Sánchez Valle and Jaime Gómez Vázquez each sold a gun to an undercover police officer. Puerto Rican prosecutors indict ed them for illegally selling firearms in violation of the Puerto Rico Arms Act of 2000. While those charges were pending, federal grand juries also indicted them, based on the same transactions, for viola tions of analogous U. S. gun trafficking statutes. Both defendants pleaded guilty to the federal charges and moved to dismiss the pend ing Commonwealth charges on double jeopardy grounds. The trial court in each case dismissed the charges, rejecting prosecutors’ ar guments that Puerto Rico and the United States are separate sover eigns for double jeopardy purposes and so could bring successive prosecutions against each defendant. The Puerto Rico Court of Ap peals consolidated the cases and reversed. The Supreme Court of Puerto Rico granted review and held, in line with the trial court, that Puerto Rico’s gun sale prosecutions violated the Double Jeopardy Clause. -

A Study of the Significant Relationships Between the United States and Puerto Rico Since 1898

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1946 A Study of the Significant Relationships Between the United States and Puerto Rico Since 1898 Mary Hyacinth Adelson Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Adelson, Mary Hyacinth, "A Study of the Significant Relationships Between the United States and Puerto Rico Since 1898" (1946). Master's Theses. 26. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/26 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1946 Mary Hyacinth Adelson A STUDY OF THE SIGNIFICANT RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND PUERTO RICO SINCE 1898 By Sister Mary Hyacinth Adelson, O.P. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements tor the Degree ot Master ot Arts in Loyola University June 1946 TABLB OF CONTBNTS CHAPTER PAGE I. PUERTO RICO: OUR LATIN-AMERICAN POSSESSION • • • • 1 Geographical features - Acquisition of the island - Social status in 1898. II. GOVERNMENT IN PUERTO RICO • • • • • • • • • • • • 15 Military Government - Transition from Spanish regime to American control - Foraker Act - Jones Bill - Accomplishments of American occupation. III. PROGRESS IN PUERTO RICO • • • • • • • • • • • • • 35 Need for greater sanitation - Education since 1898 - Agricultural problems - Commercial re lations - Industrial problems - Go~ernmental reports. IV. PUERTO RICO TODAY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 66 Attitude of Puerto Ricans toward independence - Changing opinions - Administration of Tugwell. -

Hon. Rafael Hernández Colón Gobernador Del Estado Libre Asociado De Puerto Rico 1988 TOMO II MENSAJES DEL GOBERNADOR DE PUERTO RICO HON

MENSAJES Hon. Rafael Hernández Colón Gobernador del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico 1988 TOMO II MENSAJES DEL GOBERNADOR DE PUERTO RICO HON. RAFAEL HERNANDEZ COLON AÑO 1988 - TOMO II INDICE MENSAJE CON MOTIVO DE LA ENTREGA DE BECAS DE LA ADMINISTRACION DE FOMENTO ECONOMICO A ESTUDIANTES DE PUERTO RICO Y EL CARIBE 5 DE AGOSTO DE 1988 MENSAJE ANTE LA CONVENCION ANUAL DE LA ASOCIACION DE CONSTRUCTORES DE HOGARES 5 DE AGOSTO DE 1988 MENSAJE EN LA CEREMONIA DE FIRMA DE LA R. C. DEL S. 2213 PARA ASIGNAR 3.5 MILLONES DE DOLARES A LA AUTORIDAD DE ACUEDUCTOS Y ALCANTARILLADOS A FIN DE INSTALAR UNA LINEA SUBMARINA DE AGUA POTABLE DE VIEQUES A CULEBRA 9 DE AGOSTO DE 1988 MENSAJE EN LA CEREMONIA DE LA FIRMA DEL P. DEL S. 1436 QUE AUTORIZA EL CONTROL DE ACCESO COMO MEDIDA PARA COMBATIR EL CRIMEN Y ENTREGA DE DOS CLINICAS RODANTES AL DEPARTAMENTO DE SERVICIOS CONTRA LA ADICCION 10 DE AGOSTO DE 1988 MENSAJE EN CEREMONIA DE FIRMA DEL P. DE LA C. 1416 QUE AMPLIA LOS BENEFICIOS DE LOS SOCIOS DE LA ASOCIACION DE EMPLEADOS DEL ELA Y EL P. DEL S. 1420 PARA AUTORIZAR EL DESCUENTO VOLUNTARIO DE SALARIO PARA DONACIONES BENEFICAS. 11 DE AGOSTO DE 1988 MENSAJE SOBRE EL ESTADO Y FUTURO DE LA AGRICULTURA Y FIRMA DEL P. DEL S. 1233 SOBRE SEGUROS AGRICOLAS 11 DE AGOSTO DE 1988 MENSAJE CON MOTIVO DE FIRMAR LA PROCLAMA DE LA SEMANA DEL SEGURO SOCIAL 12 DE AGOSTO DE 1988 MENSAJE EN LA CEREMONIA DE FIRMA DEL PROYECTO P. -

The Insular Cases: the Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid

ARTICLES THE INSULAR CASES: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A REGIME OF POLITICAL APARTHEID BY JUAN R. TORRUELLA* What's in a name?' TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 284 2. SETFING THE STAGE FOR THE INSULAR CASES ........................... 287 2.1. The Historical Context ......................................................... 287 2.2. The A cademic Debate ........................................................... 291 2.3. A Change of Venue: The Political Scenario......................... 296 3. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ............................................ 300 4. THE PROGENY OF THE INSULAR CASES ...................................... 312 4.1. The FurtherApplication of the IncorporationTheory .......... 312 4.2. The Extension of the IncorporationDoctrine: Balzac v. P orto R ico ............................................................................. 317 4.2.1. The Jones Act and the Grantingof U.S. Citizenship to Puerto Ricans ........................................... 317 4.2.2. Chief Justice Taft Enters the Scene ............................. 320 * Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. This article is based on remarks delivered at the University of Virginia School of Law Colloquium: American Colonialism: Citizenship, Membership, and the Insular Cases (Mar. 28, 2007) (recording available at http://www.law.virginia.edu/html/ news/2007.spr/insular.htm?type=feed). I would like to recognize the assistance of my law clerks, Kimberly Blizzard, Adam Brenneman, M6nica Folch, Tom Walsh, Kimberly Sdnchez, Anne Lee, Zaid Zaid, and James Bischoff, who provided research and editorial assistance. I would also like to recognize the editorial assistance and moral support of my wife, Judith Wirt, in this endeavor. 1 "What's in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet." WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, ROMEO AND JULIET act 2, sc. 1 (Richard Hosley ed., Yale Univ. -

La Masacre De Ponce: Una Revelación Documental Inédita

LUIS MUÑOZ MARÍN, ARTHUR GARFIELD HAYS Y LA MASACRE DE PONCE: UNA REVELACIÓN DOCUMENTAL INÉDITA Por Carmelo Rosario Natal Viejos enfoques, nuevas preguntas Al destacar el cultivo de la historia de la memoria como uno de los tópicos en auge dentro la llamada “nueva historia cultural”, el distinguido académico de la Universidad de Cambridge, Peter Burke, hace el siguiente comentario en passant: “En cambio disponemos de mucho menos investigación…sobre el tema de la amnesia social o cultural, más escurridizo pero posiblemente no menos importante.”1 Encuentro en esta observación casual de Burke la expresión de una de mis preocupaciones como estudioso. Efectivamente, hace mucho tiempo he pensado en la necesidad de una reflexión sistemática sobre las amnesias, silencios y olvidos en la historia de Puerto Rico. La investigación podría contribuir al aporte de perspectivas ignoradas, consciente o inconscientemente, en nuestro acervo historiográfico. Lo que divulgo en este escrito es un ejemplo típico de esa trayectoria de amnesias y olvidos. La Masacre de Ponce ha sido objeto de una buena cantidad de artículos, ensayos, comentarios, breves secciones en capítulos de libros más generales y algunas memorias de coetáneos. Existe una tesis de maestría inédita (Sonia Carbonell, Blanton Winship y el Partido Nacionalista, UPR, 1984) y dos libros publicados recientemente: (Raúl Medina Vázquez, Verdadera historia de la Masacre de Ponce, ICPR, 2001 y Manuel E. Moraza Ortiz, La Masacre de Ponce, Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas, 2001). No hay duda de que los eventos de marzo de 1937 en Ponce se conocen hoy con mucho más detalles en la medida en que la historiografía y la memoria patriótica nacional los han mantenido como foco de la culminación a que conducía la dialéctica de la violencia entre el estado y el nacionalismo en la compleja década de 1930. -

Sitios Arqueológicos De Ponce

Sitios Arqueológicos de Ponce RESUMEN ARQUEOLÓGICO DEL MUNICIPIO DE PONCE La Perla del Sur o Ciudad Señorial, como popularmente se le conoce a Ponce, tiene un área de aproximadamente 115 kilómetros cuadrados. Colinda por el oeste con Peñuelas, por el este con Juana Díaz, al noroeste con Adjuntas y Utuado, y al norte con Jayuya. Pertenece al Llano Costanero del Sur y su norte a la Cordillera Central. Ponce cuenta con treinta y un barrios, de los cuales doce componen su zona urbana: Canas Urbano, Machuelo Abajo, Magueyes Urbano, Playa, Portugués Urbano, San Antón, Primero, Segundo, Tercero, Cuarto, Quinto y Sexto, estos últimos seis barrios son parte del casco histórico de Ponce. Por esta zona urbana corren los ríos Bucaná, Portugués, Canas, Pastillo y Matilde. En su zona rural, los barrios que la componen son: Anón, Bucaná, Canas, Capitanejo, Cerrillos, Coto Laurel, Guaraguao, Machuelo Arriba, Magueyes, Maragüez, Marueño, Monte Llanos, Portugués, Quebrada Limón, Real, Sabanetas, San Patricio, Tibes y Vallas. Ponce cuenta con un rico ajuar arquitectónico, que se debe en parte al asentamiento de extranjeros en la época en que se formaba la ciudad y la influencia que aportaron a la construcción de las estructuras del casco urbano. Su arquitectura junto con los yacimientos arqueológicos que se han descubierto en el municipio, son parte del Inventario de Recursos Culturales de Ponce. Esta arquitectura se puede apreciar en las casas que fueron parte de personajes importantes de la historia de Ponce como la Casa Paoli (PO-180), Casa Salazar (PO-182) y Casa Rosaly (PO-183), entre otras. Se puede ver también en las escuelas construidas a principios del siglo XX: Ponce High School (PO-128), Escuela McKinley (PO-131), José Celso Barbosa (PO-129) y la escuela Federico Degetau (PO-130), en sus iglesias, la Iglesia Metodista Unida (PO-126) y la Catedral Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (PO-127) construida en el siglo XIX. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimosexta Asamblea Legislativa Quinta Sesion Ordinaria Año 2011 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOSEXTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA QUINTA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 2011 VOL. LIX San Juan, Puerto Rico Miércoles, 12 de enero de 2011 Núm. 2 A las once y treinta y ocho minutos de la mañana (11:38 a.m.) de este día, miércoles, 12 de enero de 2011, el Senado reanuda sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia de la señora Margarita Nolasco Santiago, Vicepresidenta. ASISTENCIA Senadores: Roberto A. Arango Vinent, Luz Z. Arce Ferrer, Luis A. Berdiel Rivera, Eduardo Bhatia Gautier, Norma E. Burgos Andújar, José L. Dalmau Santiago, José R. Díaz Hernández, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora, Alejandro García Padilla, Sila María González Calderón, José E. González Velázquez, Juan E. Hernández Mayoral, Héctor Martínez Maldonado, Angel Martínez Santiago, Luis D. Muñiz Cortés, Eder E. Ortiz Ortiz, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Itzamar Peña Ramírez, Kimmey Raschke Martínez, Carmelo J. Ríos Santiago, Thomas Rivera Schatz, Melinda K. Romero Donnelly, Luz M. Santiago González, Lawrence Seilhamer Rodríguez, Antonio Soto Díaz, Lornna J. Soto Villanueva, Jorge I. Suárez Cáceres, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Carlos J. Torres Torres, Evelyn Vázquez Nieves y Margarita Nolasco Santiago, Vicepresidenta. SRA. VICEPRESIDENTA: Se reanudan los trabajos del Senado de Puerto Rico hoy, miércoles, 12 de enero de 2011, a las once y treinta y ocho de la mañana (11:38 a.m.). SR. ARANGO VINENT: Señora Presidenta. SRA. VICEPRESIDENTA: Señor Portavoz. SR. ARANGO VINENT: Señora Presidenta, solicitamos que se comience con la Sesión Especial en homenaje a Roberto Alomar Velázquez, por haber sido exaltado al Salón de la Fama del Béisbol de las Grandes Ligas.