Sacred Sites of the Dalai Lamas / Glenn H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tibetan Monastery Immersion Retreat February Losar 2020

Tibetan Monastery Immersion Retreat February Losar 2020 Organized by the Panchen Lama Tashi Lhunpo Project 1 DISCOVER WITH US this journey of a lifetime. Join the Panchen Lama Tashi Lhunpo Project for a unique immersion experience at the Tashi Lhunpo Monastery India, one of the largest Learning Centers of Tibetan Buddhism in India, and participate in Losar 2020, an incredible celebration of the Tibetan New Year! We are very excited to present a unique opportunity to live within a Tibetan monastery and make a meaningful contribution to the lives of over 400 scholarly monks. By attending this retreat you will be supporting a global cause that is far-reaching for the benefit of all sentient beings. You will experience true generosity of spirit during the many activities including your meal offering for the monks and an individual book offering to the new library. By no means an ordinary monastery, Tashi Lhunpo Monastery India is steeped in historical significance. The original Tashi Lhunpo Monastery in Tibet was founded by His Holiness the 1st Dalai Lama, Gyalwa Gedun Drupe in 1447, and became the largest, most vibrant teaching monastery in Shigatse, Tibet at that time. “Namla Nyi-ma Dawa, Sa la Gyawa-Panchen.” Thus goes the age-old Tibetan saying that is well known and recited often in all 3 provinces of Tibet. It means, “Just as the Sun and the Moon in the Sky, thus Gyawa-Panchen on Earth,” alluding to the great and consequential relationship between the two Lamas, His Holiness the Dalai Lama and His Holiness the Panchen Lama, who have shared a special bond, strengthened by their shared desire to ensure the wellbeing of the Tibetan people and the continued preservation of the Buddha Dharma. -

Dangerous Truths

Dangerous Truths The Panchen Lama's 1962 Report and China's Broken Promise of Tibetan Autonomy Matthew Akester July 10, 2017 About the Project 2049 Institute The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s mid-point. Located in Arlington, Virginia, the organization fills a gap in the public policy realm through forward-looking, region-specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its interdisciplinary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. About the Author Matthew Akester is a translator of classical and modern literary Tibetan, based in the Himalayan region. His translations include The Life of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, by Jamgon Kongtrul and Memories of Life in Lhasa Under Chinese Rule by Tubten Khetsun. He has worked as consultant for the Tibet Information Network, Human Rights Watch, the Tibet Heritage Fund, and the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, among others. Acknowledgments This paper was commissioned by The Project 2049 Institute as part of a program to study "Chinese Communist Party History (CCP History)." More information on this program was highlighted at a conference titled, "1984 with Chinese Characteristics: How China Rewrites History" hosted by The Project 2049 Institute. Kelley Currie and Rachael Burton deserve special mention for reviewing paper drafts and making corrections. The following represents the author's own personal views only. TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Image: Mao Zedong (centre), Liu Shaoqi (left) meeting with 14th Dalai Lama (right 2) and 10th Panchen Lama (left 2) to celebrate Tibetan New Year, 1955 in Beijing. -

Radiant Transmission Is an October Gallery Touring Exhibition

RICHARD WILLIAMSON, Vajra-Kilaya, 1992, Height 37cm, Gilt Bronze, Iron and Polychrome Cover: CHEWANG DORJE LAMA (Boudnath, Kathmandu, Nepal), Chemchog Heruka (Mahottara), 2002, Gold and Gouache on Black Cotton Ground, 82cm x 59cm A LONG LOOK HOMEWARD Acknowledgements Photographic Images of Tibet In association with Tibet House Trust The October Gallery extends particular thanks to: Tibet House Trust, UK charity no 1037230 Robert Beer Tibet House, 1 Culworth Street, Zara Fleming London NW8 7AF Mrs Kesang Takla (Representative of the Dalai Lama in tel: 020 77225378, fax: 020 7722 0362 Northern Europe) email: [email protected], The Venerable Chime Rinpoche www.tibet-housetrust.co.uk Anthony Aris Right: Joseph Houseal, Core of Culture GONKAR GYATSO, Sue Byrne, Tibet Foundation Ecdysis II, 2003. Chewang Dorje Lama Photographic Installation Phunsok Tshering Lama (One of Four). Karen Boston The Royal Academy Below: Peacock Productions CHAM: Tibetan Sacred Dance Lamayuru, Ladakh, 2000 The October Gallery gratefully acknowledges the Photograph by Joseph support of the Arts Council England for the financial Houseal, CORE OF CULTURE. assistance that enabled this exhibition to take place. The October Gallery Education Department is supported by JP Morgan Fleming Charities and the Lloyds TSB Foundation. We acknowledge the kind permission to screen the following films: Himalaya - Momentum Films, London Tantra of Gyuto - Mystic Fire Video, New York Radiant Transmission is an October Gallery Touring Exhibition A LONG HOMEWARD, Photograph, Tibet Museum, Dharamsala. Meanwhile, in Nepal, the tantric artistic tradition has continued uninterrupted for over a thousand years and is currently undergoing a renaissance. Exquisite masterpieces of tantric art by outstanding contemporary Newar artists form the main core of this exhibition. -

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora Beyond Tibet

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora beyond Tibet Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Dias- pora beyond Tibet.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 7–32. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/uranchimeg. Abstract This article discusses a Khalkha reincarnate ruler, the First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar, who is commonly believed to be a Géluk protagonist whose alliance with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas was crucial to the dissemination of Buddhism in Khalkha Mongolia. Za- nabazar’s Géluk affiliation, however, is a later Qing-Géluk construct to divert the initial Khalkha vision of him as a reincarnation of the Jonang historian Tāranātha (1575–1634). Whereas several scholars have discussed the political significance of Zanabazar’s rein- carnation based only on textual sources, this article takes an interdisciplinary approach to discuss, in addition to textual sources, visual records that include Zanabazar’s por- traits and current findings from an ongoing excavation of Zanabazar’s Saridag Monas- tery. Clay sculptures and Zanabazar’s own writings, heretofore little studied, suggest that Zanabazar’s open approach to sectarian affiliations and his vision, akin to Tsongkhapa’s, were inclusive of several traditions rather than being limited to a single one. Keywords: Zanabazar, Géluk school, Fifth Dalai Lama, Jebtsundampa, Khalkha, Mongo- lia, Dzungar Galdan Boshogtu, Saridag Monastery, archeology, excavation The First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar (1635–1723) was the most important protagonist in the later dissemination of Buddhism in Mongolia. Unlike the Mongol imperial period, when the sectarian alliance with the Sakya (Tib. -

The Life and Times of Mingyur Peldrön: Female Leadership in 18Th Century Tibetan Buddhism

The Life and Times of Mingyur Peldrön: Female Leadership in 18th Century Tibetan Buddhism Alison Joyce Melnick Ann Arbor, Michigan B.A., University of Michigan, 2003 M.A., University of Virginia, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia August, 2014 ii © Copyright by Alison Joyce Melnick All Rights Reserved August 2014 iii Abstract This dissertation examines the life of the Tibetan nun Mingyur Peldrön (mi 'gyur dpal sgron, 1699-1769) through her hagiography, which was written by her disciple Gyurmé Ösel ('gyur med 'od gsal, b. 1715), and completed some thirteen years after her death. It is one of few hagiographies written about a Tibetan woman before the modern era, and offers insight into the lives of eighteenth century Central Tibetan religious women. The work considers the relationship between members of the Mindröling community and the governing leadership in Lhasa, and offers an example of how hagiographic narrative can be interpreted historically. The questions driving the project are: Who was Mingyur Peldrön, and why did she warrant a 200-folio hagiography? What was her role in her religious community, and the wider Tibetan world? What do her hagiographer's literary decisions tell us about his own time and place, his goals in writing the hagiography, and the developing literary styles of the time? What do they tell us about religious practice during this period of Tibetan history, and the role of women within that history? How was Mingyur Peldrön remembered in terms of her engagement with the wider religious community, how was she perceived by her followers, and what impact did she have on religious practice for the next generation? Finally, how and where is it possible to "hear" Mingyur Peldrön's voice in this work? This project engages several types of research methodology, including historiography, semiology, and methods for reading hagiography as history. -

Source 10:10 Kopi

Back to Source Journeying Tibet 22th of April to the 11th of May 2019 Back to Source Journeying Tibet 22th of April to the 11th of May 2019 Yamdrok Lake This is an invitation to a rare and fantastic journey, into one of the most important and deep spirituel cultures, in the world – the ancient Tibetan culture. Monastory of Ganden Journeying Tibet 22th of April to the 11th of May 2019 The Invitation The culture on the top of the Everything experienced in a world – is a culture that for human life, is experienced many years have lived an through one self and witnessed isolated life – it is going deep from the consciousness through into the very core of human and awareness – that’s the individual beyond human experiences. journey. It is also an invitation into Together, we travel on our own spirituality - exploring the only individual journey. This spirituality there is – your own. togetherness gives everyone support and courage to accept This journey will day by day all the gifts, that Tibetan culture lead you deeper and deeper into has to offer. the unknown By doing this things starts to By accepting this invitation you build up and our common will be a part of a group that journey becomes the vehicle for will be traveling together, on this deeper and higher experiences, 21 days journey and possible transformations. - a journey that might be, the journey of your life Monastory of Sera Journeying Tibet 22th of April to the 11th of May 2019 The journey This is fantastic ! Fantastic because of the beauty By connecting with this of the culture – fantastic environment and such a deep because of the energy ruling on tradition for energy work, as the the different places. -

WHV- Protect Swayambhu, Nepal, Volunteers Initiative Nepal

WHV – Protect Swayambhu Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Cultural property inscribed on the 17/09/2016 - 29/09/2016 World Heritage List since 1979 Located in the foothills of the Himalayas, the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage property is inscribed as seven Monument Zones. As Buddhism and Hinduism developed and changed over the centuries throughout Asia, both religions prospered in Nepal and produced a powerful artistic and architectural fusion beginning at least from the 5th century AD, but truly coming into its own in the three-hundred-year-period between 1500 and 1800 AD. These monuments were defined as the outstanding cultural traditions of the Newars, manifested in their unique urban settlements, buildings and structures with intricate ornamentation displaying outstanding craftsmanship in brick, stone, timber and bronze that are some of the most highly © TTC developed in the world. Project objectives: Swayambhu stupa and its surroundings have been dramatically damaged by the 2015 earthquake, and a first World Heritage Volunteers camp has successfully taken place in December of the same year. Following up on the work and partnerships developed, the project aims at supporting the local authorities and experts in the important reconstruction and renovation work ongoing, and at running promotional, and educational activities to further sensitize the local population and visitors about the protection of the site. Project activities: The volunteers will be directly involved in the undergoing renovation work, supporting the local experts and authorities to preserve the area and continue the reconstruction work started after the earthquake. After receiving targeted training by local experts, the participants will also run an educational campaign on the history and importance of the site and its needs and threats, aiming at reaching out to the community and in particular to the students of local universities and colleges. -

The All-In-One Audiobook

When it comes to meditation, Pema Chödrön is widely regarded as one of the world’s foremost teachers. Yet she’s never offered an introductory course on audio—until now. In How THE ALL-IN-ONE AUDIOBOOK to Meditate with Pema Chödrön, the American-born Tibetan Buddhist nun and bestselling author presents her first complete spoken-word course for those new to meditation. In these 12 sitting sessions, Pema Chödrön will help you honestly meet and compassionately relate with your mind as you explore: • The basics of mindfulness awareness practice, from proper posture to learning to settle to breathing and relaxation • Gentleness, patience, and humor—three ingredients for a well-balanced practice • Shamatha (or calm abiding), the art of stabilizing the mind to remain present with whatever arises • Thoughts and emotions as “sheer delight”—instead of obstacles—in meditation “From my own experience and from listening to many people over the years, I’ve tried to offer here what I feel are the essential points of meditation,” explains Pema Chödrön. Now this beloved voice shares with you her accessible approach—simple and down-to-earth while informed by the highest traditions of Tibetan Buddhism—on How to Meditate with Pema Chödrön. Ani Pema Chödrön was born Deirdre Blomfield-Brown in 1936, in New York City. She attended Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut and graduated from the University of California at Berkeley. She taught as an elementary school teacher for many years in both New Mexico and California. While in her mid-thirties, Ani Pema traveled to the French Alps and encountered Lama Chime Rinpoche, with whom she studied for several years. -

Brief History of Dzogchen

Brief History of Dzogchen This is the printer-friendly version of: http: / / www.berzinarchives.com / web / en / archives / advanced / dzogchen / basic_points / brief_history_dzogchen.html Alexander Berzin November 10-12, 2000 Introduction Dzogchen (rdzogs-chen), the great completeness, is a Mahayana system of practice leading to enlightenment and involves a view of reality, way of meditating, and way of behaving (lta-sgom-spyod gsum). It is found earliest in the Nyingma and Bon (pre-Buddhist) traditions. Bon, according to its own description, was founded in Tazig (sTag-gzig), an Iranian cultural area of Central Asia, by Shenrab Miwo (gShen-rab mi-bo) and was brought to Zhang-zhung (Western Tibet) in the eleventh century BCE. There is no way to validate this scientifically. Buddha lived in the sixth century BCE in India. The Introduction of Pre-Nyingma Buddhism and Zhang-zhung Rites to Central Tibet Zhang-zhung was conquered by Yarlung (Central Tibet) in 645 CE. The Yarlung Emperor Songtsen-gampo (Srong-btsan sgam-po) had wives not only from the Chinese and Nepali royal families (both of whom brought a few Buddhist texts and statues), but also from the royal family of Zhang-zhung. The court adopted Zhang-zhung (Bon) burial rituals and animal sacrifice, although Bon says that animal sacrifice was native to Tibet, not a Bon custom. The Emperor built thirteen Buddhist temples around Tibet and Bhutan, but did not found any monasteries. This pre-Nyingma phase of Buddhism in Central Tibet did not have dzogchen teachings. In fact, it is difficult to ascertain what level of Buddhist teachings and practice were introduced. -

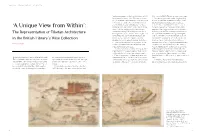

'A Unique View from Within'

Orientations | Volume 47 Number 7 | OCTOBER 2016 ‘projects in progress’ at the time of his death in 1999. (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 5). The sixth picture-map shows In my research, I use the Wise Collection as a case a 1.9-metre-long panorama of the Zangskar valley. study to examine the processes by which knowledge In addition, there are 28 related drawings showing of Tibet was acquired, collected and represented detailed illustrations of selected monasteries, and the intentions and motivations behind these monastic rituals, wedding ceremonies and so on. ‘A Unique View from Within’: processes. With the forthcoming publication of the Places on the panoramic map are consecutively whole collection and the results of my research numbered from Lhasa westwards and southwards (Lange, forthcoming), I intend to draw attention to in Arabic numerals. Tibetan numerals can be found The Representation of Tibetan Architecture this neglected material and its historical significance. mainly on the backs of the drawings, marking the In this essay I will give a general overview of the order of the sheets. Altogether there are more than in the British Library’s Wise Collection collection and discuss the unique style of the 900 numbered annotations on the Wise Collection drawings. Using examples of selected illustrations drawings. Explanatory notes referring to these of towns and monasteries, I will show how Tibetan numbers were written in English on separate sheets Diana Lange monastic architecture was embedded in picture- of paper. Some drawings bear additional labels in maps and represented in detail. Tibetan and English, while others are accompanied The Wise Collection comprises six large picture- neither by captions nor by explanatory texts. -

The Mirror No

No. 137 THE MIRROR September 2017 The Total Space of Vajrasattva The Shang Shung Foundation The Vajra Dance of Space The Community Retreats Contents Editorial. 3 The Total Space of Vajrasattva – Dorje Sempa Namkhai Che . 4 Offering Your Service to The Dzogchen Community . 9 All Hands Meeting of the Worldwide Shang Shung Foundation . 10 Five Years of the Shang Shung Institute in Russia. 18 ASIA . 22 Khaita on the Hill of the Muses. 24 Dzamling Gar . 25 Merigar West . 25 The Vajra Dance of Space . 26 Third Jewel Sangha Retreat at Merigar West. 30 Kumar Kumari All Year in School . 31 Sangha Retreats in Germany and Austria . 32 Merigar East. 33 Samtengar . 35 Japanese Sangha Retreat . 36 Tsegyalgar East . 36 Tashigar North .. 38 Journey Into Eastern Tibet . 39 Artists in the Dzogchen Community . 42 The Four Applications Above: East Tibet. Mantras on the hillside written using white cloth. of Presence . 44 Front cover: Om mani padme hum mantra carved in rock at Yihun Lhatso lake, East Tibet. Back cover: Woodblock printing press in Derge Parkhang. How I Met . 46 2 THE MIRROR · No. 137 · September 2017 of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu to reunite for Editorial five days and also introduce the Teachings to many newcomers to the Dzogchen Com- munity in the beautiful setting of Kyoto . The Resilience of the What can we learn from this? We can Dzogchen Community learn about our own capacity and resil- ience as an enormous international, often rcidosso, Paris, Munich, Vienna and unwieldy, Sangha . The Community rose Kyoto, what is the common thread to the occasion and allowed Rinpoche the Afound in all these places for the senior students and instructors, and the space to relax in the knowledge that the International Dzogchen Community? The generosity of the Sangha Rimay of Denys Dzogchen Community can take care of it- common thread is that each of these plac- Rinpoche in Paris who kindly offered their self when the need arises . -

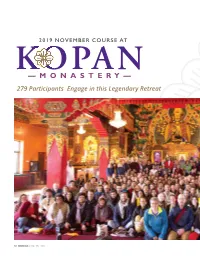

— M O N a S T E R

2019 NOVEMBER COURSE AT KOPAN —MONASTERY— 279 Participants Engage in this Legendary Retreat 52 MANDALA | Issue One 2020 Every year, the November Course, a month-long lamrim meditation course at Kopan Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal, draws diverse students from around the world. What started in 1971 with a dozen students in attendance, reached a record 279 participants from forty-nine countries this year with Ven. Robina Courtin teaching the course for the first time. This was also the first course held in Kopan’s new Chenrezig gompa. Mandala editor, Carina Rumrill asked Ven. Robina about this year’s course, and we share this beautiful account of her experience and history with this style of retreat. THIS YEAR’S RECORD NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS — 279 PEOPLE FROM FORTY-NINE COUNTRIES — WITH KOPAN’S ABBOT KHEN RINPOCHE THUBTEN CHONYI, VEN. ROBINA COURTIN, AND OTHER TEACHERS AND MEDITATION LEADERS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). Issue One 2020 | MANDALA 53 VEN. ROBINA COURTIN OFFERED A MANDALA TO RINPOCHE REQUESTING TEACHINGS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). AND THE BLESSINGS: YOU COULDN’T HELP BUT FEEL THEM BY VEN. ROBINA COURTIN The Kopan November Course is legendary. The first of what But the beauty of the place was its saving grace: a hill became an annual event, one month of lamrim teachings by surrounded on all sides by the terraced fields of the magnifi cent Lama Zopa Rinpoche to a dozen Westerners fifty years ago, Kathmandu Valley, with mountains to the north and the holy quickly became a magnet for spiritual seekers worldwide.