Four Strategies for Additions to Historic Settings “DIFFERENTIATED” and “COMPATIBLE”: FOUR STRATEGIES for ADDITIONS to HISTORIC SETTINGS by Steven W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The View from Rome

4/26/2019 The View From Rome » 2010 » April http://traditional-building.com/Steve_Semes/?m=201004 Go JAN FEB MAY ⍰ ❎ 51 captures 18 f 18 Feb 2012 - 8 Apr 2016 2011 2012 2013 ▾ About this capture The View From Rome Steven W. Semes Home About Steven W. Semes Our Other Blogs Clem Labine’s Traditional Building Clem Labine’s Period Homes Switcher Archive Archive for April, 2010 Can’t We Just Get Along? New and Old Buildings in Context April 15th, 2010 No comments What is the proper relationship between historical architecture and the production of new buildings and cities? Are architects and preservationists inevitably at odds, or is there a common objective that potentially unites them? Why do we assume that the architecture of the present and the architecture of the past are entirely different things that must be handled by entirely separate sets of experts? It is necessary to examine these questions in the light of a recovered traditional architecture and urbanism. The Louvre, Paris, shows how an architectural ensemble can grow over the course of centuries while maintaining essentially the same style. Within the courtyard, the central pavilion and the right half of the facade were designed by Jacques Lemercier to continue (and, in the case of the bays to the right of the center tower, to precisely imitate) the facade on the left half, built to the design of Pierre Lescot a century earlier. Photo: Steven W. Semes Historically, restoration or completion of old buildings and the design of new buildings were simply different aspects of a single discipline. -

Bulletin Trimestriel 3Ème Trimestre 2014 10.15 Mo

juin 2014 – 3e trimestre 2014 ÉDITORIAL Le Président, Marc FUMAROLI, de l’Académie française la société des amis du louvre Chers Amis du Louvre, a offert au musée À l’occasion de notre Assemblée générale qui s’est tenue à l’Auditorium du Louvre le n Deux dessins de Giovanni Francesco 6 mai dernier, le Président Martinez a fait connaître aux Amis du Louvre venus nombreux Romanelli : L’Enlèvement des Sabines ce jour-là, l’acquisition majeure que nous venons de faire en partenariat avec le Musée et et La Continence de Scipion dont je vous avais déjà parlé à mots couverts dans notre précédent Bulletin. n Nicolas Besnier Il s’agit d’un chef-d’œuvre de l’orfèvrerie parisienne du XVIIIe siècle : deux pots à oille Deux pots à oille du service Walpole datés de 1726 signés de l’orfèvre du Roi Nicolas Besnier (1685-1754). Ils proviennent du service de table du grand homme d’Etat anglais et grand collectionneur, Robert Walpole . Cet achat prestigieux a été fi nancé à parts égales entre le Musée et notre Société pour un montant total de 5,5 millions d’euros. Je remercie Madame Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, conservateur en chef au département des Objets d’art, de nous présenter dans ce Bulletin cette merveille de style de transition Louis XIV-Louis XV et que nous avons souhaité offrir au Musée pour compléter la fête qui se prépare lors de l’ouverture le 6 juin prochain des nouvelles salles des Arts décoratifs XVIIe-XVIIIe. Les deux pots à oille du service Walpole seront exposés en hommage aux Amis du Louvre dans la Chambre du duc de Chevreuse. -

Assessment Actions

Assessment Actions Borough Code Block Number Lot Number Tax Year Remission Code 1 1883 57 2018 1 385 56 2018 2 2690 1001 2017 3 1156 62 2018 4 72614 11 2018 2 5560 1 2018 4 1342 9 2017 1 1390 56 2018 2 5643 188 2018 1 386 36 2018 1 787 65 2018 4 9578 3 2018 4 3829 44 2018 3 3495 40 2018 1 2122 100 2018 3 1383 64 2017 2 2938 14 2018 Page 1 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions Owner Name Property Address Granted Reduction Amount Tax Class Code THE TRUSTEES OF 540 WEST 112 STREET 105850 2 COLUM 226-8 EAST 2ND STREET 228 EAST 2 STREET 240500 2 PROSPECT TRIANGLE 890 PROSPECT AVENUE 76750 4 COM CRESPA, LLC 597 PROSPECT PLACE 23500 2 CELLCO PARTNERSHIP 6935500 4 d/ CIMINELLO PROPERTY 775 BRUSH AVENUE 329300 4 AS 4305 65 REALTY LLC 43-05 65 STREET 118900 2 PHOENIX MADISON 962 MADISON AVENUE 584850 4 AVENU CELILY C. SWETT 277 FORDHAM PLACE 3132 1 300 EAST 4TH STREET H 300 EAST 4 STREET 316200 2 242 WEST 38TH STREET 242 WEST 38 STREET 483950 4 124-469 LIBERTY LLC 124-04 LIBERTY AVENUE 70850 4 JOHN GAUDINO 79-27 MYRTLE AVENUE 35100 4 PITKIN BLUE LLC 1575 PITKIN AVENUE 49200 4 GVS PROPERTIES LLC 559 WEST 164 STREET 233748 2 EP78 LLC 1231 LINCOLN PLACE 24500 2 CROTONA PARK 1432 CROTONA PARK EAS 68500 2 Page 2 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions 1 1231 59 2018 3 7435 38 2018 3 1034 39 2018 3 7947 17 2018 4 370 1 2018 4 397 7 2017 1 389 22 2018 4 3239 1001 2018 3 140 1103 2018 3 1412 50 2017 1 1543 1001 2018 4 659 79 2018 1 822 1301 2018 1 2091 22 2018 3 7949 223 2018 1 471 25 2018 3 1429 17 2018 Page 3 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions DEVELOPM 268 WEST 84TH STREET 268 WEST 84 STREET 85350 2 BANK OF AMERICA 1415 AVENUE Z 291950 4 4710 REALTY CORP. -

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 As a Masterpiece of Late Gothic Architecture

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 as a masterpiece of late Gothic architecture. The church’s reputation was strong enough of the time for it to be chosen as the location for a young Louis XIV to receive communion. Mozart also Church of Saint 2 Impasse Saint- chose the sanctuary as the location for his mother’s funeral. Among ** Unknown Eustace Eustache those baptised here as children were Richelieu, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, future Madame de Pompadour and Molière, who was also married here in the 17th century. Amazing façade. Mon-Fri (9.30am-7pm), Sat-Sun (9am-7pm) Japanese architect Tadao Ando has revealed his plans to convert Paris' Bourse de Commerce building into a museum that will host one of the world's largest contemporary art collections. Ando was commissioned to create the gallery within the heritage-listed building by French Bourse de Commerce ***** Tadao Ando businessman François Pinault, who will use the space to host his / Collection Pinault collection of contemporary artworks known as the Pinault Collection. A new 300-seat auditorium and foyer will be set beneath the main gallery. The entire cylinder will be encased by nine-metre-tall concrete walls and will span 30 metres in diameter. Opening soon The Jardin du Palais Royal is a perfect spot to sit, contemplate and picnic between boxed hedges, or shop in the trio of beautiful arcades that frame the garden: the Galerie de Valois (east), Galerie de Montpensier (west) and Galerie Beaujolais (north). However, it's the southern end of the complex, polka-dotted with sculptor Daniel Buren's Domaine National du ***** 8 Rue de Montpensier 260 black-and-white striped columns, that has become the garden's Palais-Royal signature feature. -

The Story of Architecture

A/ft CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 062 545 193 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1992. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924062545193 o o I I < y 5 o < A. O u < 3 w s H > ua: S O Q J H HE STORY OF ARCHITECTURE: AN OUTLINE OF THE STYLES IN T ALL COUNTRIES • « « * BY CHARLES THOMPSON MATHEWS, M. A. FELLOW OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS AUTHOR OF THE RENAISSANCE UNDER THE VALOIS NEW YORK D. APPLETON AND COMPANY 1896 Copyright, 1896, By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY. INTRODUCTORY. Architecture, like philosophy, dates from the morning of the mind's history. Primitive man found Nature beautiful to look at, wet and uncomfortable to live in; a shelter became the first desideratum; and hence arose " the most useful of the fine arts, and the finest of the useful arts." Its history, however, does not begin until the thought of beauty had insinuated itself into the mind of the builder. -

Architecture: the Museum As Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12

Architecture: The Museum as Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12 Program Outline & Volunteer Resource Package Single Visit Program Option : 2 HOURS Contents of Resource Package Contents Page Program Development & Description 1 Learning Objectives for Students & Preparation Guidelines 2 One Page Program Outline 3 Powerpoint Presentation Overview 4 - 24 Glossary – Architectural Terms 24 - 27 Multimedia Resource Lists (Potential Research Activities) 27 - 31 Field Journal Sample 32 - 34 Glossary – Descriptive Words Program Development This programme was conceived in conjunction with the MOA Renewal project which expanded the Museum galleries, storages and research areas. The excitement that developed during this process of planning for these expanded spaces created a renewed enthusiasm for the architecture of Arthur Erickson and the landscape architecture of Cornelia Oberlander. Over three years the programme was developed with the assistance of teacher specialists, Jane Kinegal, Cambie Secondary School and Russ Timothy Evans, Tupper Secondary School. This programme was developed under the direction of Jill Baird, Curator of Education & Public Programmes, with Danielle Mackenzie, Public Programs & Education Intern 2008/09, Jennifer Robinson, Public Programs & Education Intern 2009/10, Vivienne Tutlewski, Public Programs & Education Intern 2010/2011, Katherine Power, Public Programs & Education Workstudy 2010/11, and Maureen Richardson, Education Volunteer Associate, who were all were key contributors to the research, development and implementation of the programme. Program Description Architecture: The Museum as Muse, Grades 6 - 12 MOA is internationally recognized for its collection of world arts and culture, but it is also famous for its unique architectural setting. This program includes a hands-on phenomenological (sensory) activity, an interior and exterior exploration of the museum, a stunning visual presentation on international museum architecture, and a 30 minute drawing activity where students can begin to design their own museum. -

Renaissance Walking Tour 4

King François I, France’s “Renaissance Prince”, and his Italian-born daughter-in- law Catherine de Medici, dominated 16th-century France both politically and architecturally. François I had his hand in buildings of every kind from the Louvre palace, to the huge church of Saint-Eustache, to the Paris city hall, the Hôtel de Ville. You’ll visit these sites on this tour. Catherine de Medici shared her father-in-law’s passion for building, although almost none of her construction projects survived. But you can and will visit the Colonne de l’Horoscope, a strange remnant of what was once Catherine’s grand Renaissance palace just to the west of Les Halles market. From there, the walk takes you through the bustling Les Halles quarter, stopping to admire the elegant Renaissance-style Fontaine des Innocents and the beautifully restored Tour Saint-Jacques. The walk ends in the trendy Marais, where three Renaissance style mansions can still be admired today. Start: Louvre (Métro: Palais-Royal/Musée du Louvre) Finish: Hôtel Carnavalet/ Musée de l’Histoire de Paris (Métro: Saint-Paul) Distance: 3 miles Time: 3 - 3.5 hours Best Days: Tuesday - Sunday Copyright © Ann Branston 2011 HISTORY Religious wars dominated the age of Catherine de Medici and her three Politics and Economics sons. As the Protestant reformation spread in France, animosities and hostilities between Protestants and Catholics grew, spurred on by old family The sixteenth century was a tumultuous time in France. The country was nearly feuds and ongoing political struggles. In 1562, the Huguenots (as French bankrupted by wars in Italy and torn apart repeatedly by internal political intrigue Protestants were called) initiated the first of eight religious civil wars. -

Dissertation, Full Draft V. 3

Inventing Architectural Identity: The Institutional Architecture of James Renwick, Jr., 1818-95 Nicholas Dominick Genau Amherst, New York BA, University of Virginia, 2006 MA, University of Virginia, 2009 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McIntire Department of Art University of Virginia May, 2014 i TABLE OF CONTENTS ! ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .......................................................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1! An Architectural Eclectic:!! A Survey of the Career of James Renwick, Jr. .......................................................................................................................................................... 9! CHAPTER 2! “For the Dignity of Our Ancient and Glorious Catholic Name”:!! Renwick and Archbishop Hughes!at St. Patrick’s Cathedral ....................................................................................................................................................... -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

Domaine National Du Palais Royal -Bury Fountain

LOCATIONS N°49914 updated: 05/28/2020 Domaine National du Palais Royal -Bury fountain 75001 Paris France Contact the commission Film Paris Region, Ile-de-France Film Commission | +33 (0)1 75 62 58 07 Credits: www.l'artnouveau.com Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Caption: Caption: Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Caption: Caption: Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Caption: LOCATION TYPE CATEGORIES YARD Fountain ENVIRONMENT City GENERAL PRESENTATION LOCATION CONDITION TYPE Well maintained LOCATION HISTORY After the wall Charles V had built around Paris was torn down, Cardinal de Richelieu asked Jacques Lemercier to construct a monumental palace with a large garden near the Louvre (1634). For a long time, the palace was called the Palais Cardinal, before becoming what it is today: the Palais Royal. The prelate gave the house to the crown in 1636, and it was the residence of the Orléans family from 1661 and even became a center of power during the Regency. The main wing, which faces the Louvre, was finished and remodeled by Contant d’Ivry in the 18th century, then by Fontaine in the 19th century. The theater, today the seat of the Théâtre français, burned down on several occasions and was rebuilt in 1791. At the end of the 18th century, Louis-Philippe d’Orléans (the future Philippe-Egalité) needed money and launched a major real estate development project in 1780. He commissioned Victor Louis to build apartment buildings with identical facades around the three sides of the garden. -

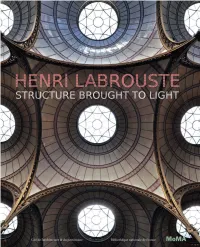

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light Is the Condensed Result of Several Years of Research, Goers Are Plunged

HENRI LABROUSTE STRUCTURE BROUGHT TO LIGHT With essays by Martin Bressani, Marc Grignon, Marie-Hélène de La Mure, Neil Levine, Bertrand Lemoine, Sigrid de Jong, David Van Zanten, and Gérard Uniack The Museum of Modern Art, New York In association with the Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine et the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the special participation of the Académie d’architecture and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. This exhibition, the first the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine has devoted to Since its foundation eighty years ago, MoMA’s Department of Architecture (today the a nineteenth-century architect, is part of a larger series of monographs dedicated Department of Architecture and Design) has shared the Museum’s linked missions of to renowned architects, from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau to Claude Parent and showcasing cutting-edge artistic work in all media and exploring the longer prehistory of Christian de Portzamparc. the artistic present. In 1932, for instance, no sooner had Philip Johnson, Henry-Russell Presenting Henri Labrouste at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine carries with Hitchcock, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., installed the Department’s legendary inaugural show, it its very own significance, given that his name and ideas crossed paths with our insti- Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, than plans were afoot for a show the following tution’s history, and his works are a testament to the values he defended. In 1858, he year on the commercial architecture of late-nineteenth-century Chicago, intended as the even sketched out a plan for reconstructing the Ecole Polytechnique on Chaillot hill, first in a series of shows tracing key episodes in the development of modern architecture though it would never be followed through. -

The Architectural Practice of Gerard Wight and William Lucas from 1885 to 1894

ABPL90382 Minor Thesis Jennifer Fowler Student ID: 1031421 22 June 2020 Boom Mannerism: The Architectural Practice of Gerard Wight and William Lucas from 1885 to 1894 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Urban and Cultural Heritage, Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne Frontispiece: Herbert Percival Bennett Photograph of Collins Street looking east towards Elizabeth Street, c.1894, glass lantern slide, Gosbel Collection, State Library of Victoria. Salway, Wight and Lucas’ Mercantile Bank of 1888 with dome at centre above tram. URL: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/54894. Abstract To date there has been no thorough research into the architectural practice of Wight and Lucas with only a few of their buildings referred to with brevity in histories and articles dealing with late nineteenth-century Melbourne architecture. The Boom era firm of Wight and Lucas from 1885 to 1894 will therefore be investigated in order to expand their catalogue of works based upon primary research and field work. Their designs will be analysed in the context of the historiography of the Boom Style outlined in various secondary sources. The practice designed numerous branches for the Melbourne Savings Bank in the metropolitan area and collaborated with other Melbourne architects when designing a couple of large commercial premises in the City of Melbourne. These Mannerist inspired classical buildings fit the general secondary descriptions of what has been termed the Boom Style of the 1880s and early 1890s. However, Wight and Lucas’ commercial work will be assessed in terms of its style, potential overseas influences and be compared to similar contemporary Melbourne architecture to firstly reveal their design methods and secondly, to attempt to give some clarity to the overall definition of Melbourne’s Boom era architecture and the firm’ place within this period.