Vector 274 Worthen 2013-Wi BSFA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

177 Mental Toughness Secrets of the World Class

177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold Published by London House www.londonhousepress.com © 2005 by Steve Siebold All Rights Reserved. Printed in Hong Kong. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Ordering Information To order additional copies please visit www.mentaltoughnesssecrets.com or visit the Gove Siebold Group, Inc. at www.govesiebold.com. ISBN: 0-9755003-0-9 Credits Editor: Gina Carroll www.inkwithimpact.com Jacket and Book design by Sheila Laughlin 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the three most important people in my life, for their never-ending love, support and encouragement in the realization of my goals and dreams. Dawn Andrews Siebold, my beautiful, loving wife of almost 20 years. You are my soul mate and best friend. I feel best about me when I’m with you. We’ve come a long way since sub-man. I love you. Walter and Dolores Siebold, my parents, for being the most loving and supporting parents any kid could ask for. Thanks for everything you’ve done for me. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

1: for Me, It Was Personal Names with Too Many of the Letter "Q"

1: For me, it was personal names with too many of the letter "q", "z", or "x". With apostrophes. Big indicator of "call a rabbit a smeerp"; and generally, a given name turns up on page 1... 2: Large scale conspiracies over large time scales that remain secret and don't fall apart. (This is not *explicitly* limited to SF, but appears more often in branded-cyberpunk than one would hope for a subgenre borne out of Bruce Sterling being politically realistic in a zine.) Pretty much *any* form of large-scale space travel. Low earth orbit, not so much; but, human beings in tin cans going to other planets within the solar system is an expensive multi-year endevour that is unlikely to be done on a more regular basis than people went back and forth between Europe and the americas prior to steam ships. Forget about interstellar travel. Any variation on the old chestnut of "robots/ais can't be emotional/creative". On the one hand, this is realistic because human beings have a tendency for othering other races with beliefs and assumptions that don't hold up to any kind of scrutiny (see, for instance, the relatively common belief in pre-1850 US that black people literally couldn't feel pain). On the other hand, we're nowhere near AGI right now and it's already obvious to everyone with even limited experience that AI can be creative (nothing is more creative than a PRNG) and emotional (since emotions are the least complex and most mechanical part of human experience and thus are easy to simulate). -

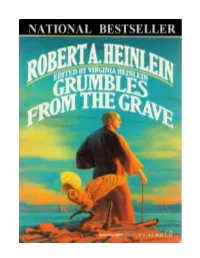

Grumbles from the Grave

GRUMBLES FROM THE GRAVE Robert A. Heinlein Edited by Virginia Heinlein A Del Rey Book BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK For Heinlein's Children A Del Rey Book Published by Ballantine Books Copyright © 1989 by the Robert A. and Virginia Heinlein Trust, UDT 20 June 1983 All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint the following material: Davis Publications, Inc. Excerpts from ten letters written by John W. Campbell as editor of Astounding Science Fiction. Copyright ® 1989 by Davis Publications, Inc. Putnam Publishing Group: Excerpt from the original manuscript of Podkayne of Mars by Robert A. Heinlein. Copyright ® 1963 by Robert A. Heinlein. Reprinted by permission of the Putnam Publishing Group. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 89-6859 ISBN 0-345-36941-6 Manufactured in the United States of America First Hardcover Edition: January 1990 First Mass Market Edition: December 1990 CONTENTS Foreword A Short Biography of Robert A. Heinlein by Virginia Heinlein CHAPTER I In the Beginning CHAPTER II Beginnings CHAPTER III The Slicks and the Scribner's Juveniles CHAPTER IV The Last of the Juveniles CHAPTER V The Best Laid Plans CHAPTER VI About Writing Methods and Cutting CHAPTER VII Building CHAPTER VIII Fan Mail and Other Time Wasters CHAPTER IX Miscellany CHAPTER X Sales and Rejections CHAPTER XI Adult Novels CHAPTER XII Travel CHAPTER XIII Potpourri CHAPTER XIV Stranger CHAPTER XV Echoes from Stranger AFTERWORD APPENDIX A Cuts in Red Planet APPENDIX B Postlude to Podkayne of Mars—Original Version APPENDIX C Heinlein Retrospective, October 6, 1988 Bibliography Index FOREWORD This book does not contain the polished prose one normally associates with the Heinlein stories and articles of later years. -

Nicoletti Emma 2014.Pdf

Reading Literature in the Anthropocene: Ecosophy and the Ecologically-Oriented Ethics of Jeff Noon’s Nymphomation and Pollen Emma Nicoletti 10012001 B.A. (Hons), The University of Western Australia, 2005 Dip. Ed., The University of Western Australia, 2006 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (English and Cultural Studies) 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the science fiction novels Nymphomation and Pollen by Jeff Noon. The reading brings together ideas from the eco-sciences, environmental humanities and ecocriticism in order to analyse the ecological dimensions of these texts. Although Noon’s work has been the subject of academic critique, critical discussions of his oeuvre have overlooked the engagement of Nymphomation and Pollen with ecological issues. This is a gap in the scholarship on Noon’s work that this thesis seeks to rectify. These novels depict landscapes and communities as being degraded because of the influence of information technologies and homogeneous ideologies, making them a productive lens through which to consider and critically respond to some of the environmental and social challenges faced by humanity in an anthropogenic climate. In order to discuss the ecological dimensions of these novels, the thesis advances the notion of an “ecosophical reading practice.” This idea draws on Felix Guattari’s concept of “ecosophy,” and combines it with the notions of “ecological thinking” developed in the work of theorists Timothy Morton, Lorraine Code and Gregory Bateson. While Morton’s work is extensively cited in ecocritical scholarship, with a few exceptions, the work of the other theorists is not. -

Organizing Books and Did This Process, I Discovered That Two of Them Had a Really Yucky Feeling to Them

Jennifer Hofmann Inspired Home Office © 2014 This graphic is intentionally small to save your printer ink.:) 1 Inspired Home Office: The Book First edition Copyright 2014 Jennifer E. Hofmann, Inspired Home Office All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded, or otherwise without written permission by the author. This publication contains the opinion and ideas of the author. It is intended to provide helpful and informative material on the subject matter covered, and is offered with the understanding that the author is not engaged in rendering professional services in this publication. If the reader requires legal, financial or other professional assistance or advice, a qualified professional should be consulted. No liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. Although every precaution has been taken to produce a high quality, informative, and helpful book, the author makes no representation or warranties of any kind with regard to the completeness or accuracy of the contents of the book. The author specifically disclaims any responsibility for any liability, loss or risk, personal or otherwise, which is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, from the use and application of any of the contents of this publication. Jennifer Hofmann Inspired Home Office 3705 Quinaby Rd NE Salem, OR 97303 www.inspiredhomeoffice.com 2 Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................. -

Vector 273 Worthen 2013-Fa BSFA

VECTOR 273 — AUTUMN 2013 Vector The critical journal of the British Science Fiction Association Best of 2012 Issue No. 273 Autumn 2013 £4.00 page 1 VECTOR 273 — AUTUMN 2013 Vector 273 The critical journal of the British Science Fiction Association ARTICLES Torque Control Vector Editorial by Shana Worthen ........................ 3 http://vectoreditors.wordpress.com BSFA Review: Best of 2012 Features, Editorial Shana Worthen Edited by Martin Lewis ................................ 4 and Letters: 127 Forest Road, Loughton, Essex IG10 1EF, UK [email protected] In Review: The Best of US Science Fiction Book Reviews: Martin Lewis Television, 2012 14 Antony House, Pembury Sophie Halliday ........................................... 10 Place, London E5 8GZ Production: Alex Bardy UK SF Television 2012: Dead things that [email protected] will not die Alison Page ..................................................12 British Science Fiction Association Ltd The BSFA was founded in 1958 and is a non-profitmaking organisation entirely staffed by unpaid volunteers. Registered in England. Limited 2012 in SF Audio by guarantee. Tony Jones ................................................... 15 BSFA Website www.bsfa.co.uk Company No. 921500 Susan Dexter: Fantasy Bestowed Registered address: 61 Ivycroft Road, Warton, Tamworth, Mike Barrett ................................................ 19 Staffordshire B79 0JJ President Stephen Baxter Vice President Jon Courtenay Grimwood RECURRENT Foundation Favourites: Andy Sawyer ... 24 Chair Ian Whates [email protected] Kincaid in Short: Paul Kincaid ................. 26 Treasurer Martin Potts Resonances: Stephen Baxter ................... 29 61 Ivy Croft Road, Warton, Nr. Tamworth B79 0JJ [email protected] THE BSFA REVIEW Membership Services Peter Wilkinson Inside The BSFA Review ............................ 33 Flat 4, Stratton Lodge, 79 Bulwer Rd, Barnet, Hertfordshire EN5 5EU Editorial by Martin Lewis........................... -

April 2018 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle April 2018 The Next NASFA Meeting is 6P Saturday 21 April 2018 at the New Church Location All other months are definitely open.) d Oyez, Oyez d FUTURE CLUB MEETING DATES/LOCATIONS At present, all 2018 NASFA Meetings are expected to be at The next NASFA Meeting will be 21 April 2018, at the reg- the normal meeting location except for October (due to Not-A- ular meeting location and the NEW regular time (6P). The Con 2018). Most 2018 meetings are on the normal 3rd Saturday. Madison campus of Willowbrook Baptist Church is at 446 Jeff The only remaining meeting currently not scheduled for the Road—about a mile from the previous location. See the map normal weekend is: below for directions to the church. See the map on page 2 for a •11 August—a week earlier (2nd Saturday) to avoid Worldcon closeup of parking at the church as well as how to find the CHANGING SHUTTLE DEADLINES meeting room (“The Huddle”), which is close to one of the In general, the monthly Shuttle production schedule has been back doors toward the north side of the church. Please do not moved to the left a bit (versus prior practice). Though things try to come in the (locked) front door. are a bit squishy, the current intent is to put each issue to bed APRIL PROGRAM about 6–8 days before each month’s meeting. Les Johnson will speak on “Graphene—The Superstrong, Please check the deadline below the Table of Contents each Superthin, and Superversatile Material That Will Revolutionize month to submit news, reviews, LoCs, or other material. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

BSFG News 482 November 2011

NOVACON 41 will be held over the Brum Group News weekend of November 11th to the 13th at The Monthly Newsletter of the The Park Inn, 296 Mansfield Road, BIRMINGHAM SCIENCE FICTION GROUP Nottingham. NG5 2BT. The Guest of November 2011 Issue 482 Honour will be SF author JOHN Honorary Presidents: BRIAN W ALDISS, O.B.E. MEANEY. Further details can be found & HARRY HARRISON on the website http://novacon.org.uk/ Committee: Vernon Brown (Chairman); Pat Brown (Treasurer); Theresa Derwin (Secretary); Rog Peyton (Newsletter Editor); Dave Corby (publicity Officer); William McCabe (Website); Vicky Stock (Membership secretary); BRUM GROUP NEWS #481 (October 2011) copyright 2011 for Birmingham NOVACON 41 Chairman: Steve Lawson SF Group. Designed by Rog Peyton (19 Eves Croft, Bartley Green, Birmingham, website: Email: www.birminghamsfgroup.org.uk/ [email protected] B32 3QL – phone 0121 477 6901 or email rog [dot] peyton [at] btinternet [dot] com). Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the committee or the general membership or, for that matter, the person giving the ‘opinion’. th Thanks to all the named contributors in this issue and to William McCabe who Friday 4 November sends me reams of news items every month which I sift through for the best/most entertaining items. IAN WHATES Ian Whates’ earliest memories of science fiction are fragmented. He remembers loving Dr Who and other TV SF shows from an early age, but a defining moment came when he heard a radio adaptation of John Wyndham’s THE CHRYSALIDS. From that moment on he was hooked and haunted the local library, voraciously devouring the contents of their SF section. -

IRS December 2012 Was Prepared in Melbourne, Australia, for Display on Efanzines At

2 December 2012 for display on eFanzines at: www.efanzines.com Feedback encouraged Please e-mail your letter of comment to: [email protected] Editorial At the back of IRS September 2012 is a report on an important Australian breakthrough in quantum computing. This time, authored by the editor and scientist Dick (Ditmar) Jenssen who does cover graphics for this excellent journal, we put right up front the literary and mathematical dimensions of Special Relativity. Find out what are the best SF stories on relativistic travel and revel in the elegant math. It starts on Page 8. Contents This issue’s cover ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 CSIRAC and Science Fiction ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Relativistic travel .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Letters from (North) America ............................................................................................................................................. 15 Norma K Hemming Award 2013 ....................................................................................................................................... 16 Andrew Porter encourages last minute fanac on the 2013 GUFF race .............................................................................. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Semiotext SF by Rudy Rucker Semiotext SF by Rudy Rucker

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Semiotext SF by Rudy Rucker Semiotext SF by Rudy Rucker. ISBN 0-936756-43-8 (US pbk), ISSN 0-093-95779 (US pbk) Anthology edited by Peter Lamborn Wilson, Rudy Rucker, Robert Anton Wilson. Front cover art, Mike Saenz. Design, Sue Ann Harkey. Back cover art & design, Steve Jones. " The Toshiba H-P Waldo " ad art by Mike Saenz; " Metamorphosis No.89 " by Don Webb, " We See Things Differently " by Bruce Sterling (short story. also contained in the collection Globalhead by Bruce Sterling, 1992), " Portfolio " collages by Freddie Baer, " America Comes " poem by Bruce Boston, " Frankenstein Penis " by Ernest Hogan (short story. followed by the sequel: "The Dracula Vagina"), " Six Kinds of Darkness " excerpt from A Song Called Youth by John Shirley (short story. also contained in the collection Heatseeker by John Shirley, 1989), " On Eve of Physics Symposium, More Sub-Atomic Particles Found " by Nick Herbert, " Burning Sky " by Rachel Pollack, " Day " poem by Bob McGlynn, " Rapture in Space " by Rudy Rucker (short story, written in Lynchburg, Fall 1984. re-issued in the collection Transreal! by Rudy Rucker, WCS, 1991), " Quent Wimpel Meets Bigfoot " by Kerry Thornley, " Hippie Hat Brain Parasite " by William Gibson, " The Great Escape " by Sol Yurick, " Portfolio " collages by James Koehnline, " Jane Fonda's Augmentation Mammoplasty " by J.G.Ballard, " Report on an Unidentified Space Station " by J.G.Ballard (originally published in the magazine City Limits , December 1982), " Is This True? Well, Yes and No " by Sharon Gannon