Millions on the Move Understanding Climate Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slow-Onset Processes and Resulting Loss and Damage

Publication Series ADDRESSING LOSS AND DAMAGE FROM SLOW-ONSET PROCESSES Slow-onset Processes and Resulting Loss and Damage – An introduction Table of contents L 4 22 ist of a bbre Summary of Loss and damage via tio key facts and due to slow-onset ns definitions processes AR4 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report 6 22 What is loss and damage? Introduction AR5 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report COP Conference of the Parties to the 23 United Nations Framework Convention on 9 What losses and damages IMPRINT Climate Change can result from slow-onset Slow-onset ENDA Environment Development Action Energy, processes? Authors Environment and Development Programme processes and their Laura Schäfer, Pia Jorks, Emmanuel Seck, Energy key characteristics 26 Oumou Koulibaly, Aliou Diouf ESL Extreme Sea Level What losses and damages Contributors GDP Gross Domestic Product 9 can result from sea level rise? Idy Niang, Bounama Dieye, Omar Sow, Vera GMSL Global mean sea level What is a slow-onset process? Künzel, Rixa Schwarz, Erin Roberts, Roxana 31 Baldrich, Nathalie Koffi Nguessan GMSLR Global mean sea level rise 10 IOM International Organization on Migration What are key characteristics Loss and damage Editing Adam Goulston – Scize Group LLC of slow-onset processes? in Senegal due to IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sea level rise Layout and graphics LECZ Low-elevation coastal zone 14 Karin Roth – Wissen in Worten OCHA Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs What are other relevant January 2021 terms for the terminology on 35 RCP Representative -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

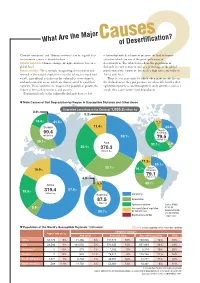

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Assessing Climate Change's Contribution to Global Catastrophic

Assessing Climate Change’s Contribution to Global Catastrophic Risk Simon Beard,1,2 Lauren Holt,1 Shahar Avin,1 Asaf Tzachor,1 Luke Kemp,1,3 Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh,1,4 Phil Torres, and Haydn Belfield1 5 A growing number of people and organizations have claimed climate change is an imminent threat to human civilization and survival but there is currently no way to verify such claims. This paper considers what is already known about this risk and describes new ways of assessing it. First, it reviews existing assessments of climate change’s contribution to global catastrophic risk and their limitations. It then introduces new conceptual and evaluative tools, being developed by scholars of global catastrophic risk that could help to overcome these limitations. These connect global catastrophic risk to planetary boundary concepts, classify its key features, and place global catastrophes in a broader policy context. While not yet constituting a comprehensive risk assessment; applying these tools can yield new insights and suggest plausible models of how climate change could cause a global catastrophe. Climate Change; Global Catastrophic Risk; Planetary Boundaries; Food Security; Conflict “Understanding the long-term consequences of nuclear war is not a problem amenable to experimental verification – at least not more than once" Carl Sagan (1983) With these words, Carl Sagan opened one of the most influential papers ever written on the possibility of a global catastrophe. “Nuclear war and climatic catastrophe: Some policy implications” set out a clear and credible mechanism by which nuclear war might lead to human extinction or global civilization collapse by triggering a nuclear winter. -

Re-Thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification

Overcoming One of the Greatest Environmental Challenges of Our Times: Re-thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification Authors: Zafar Adeel, Janos Bogardi, Christopher Braeuel, Pamela Chasek, Maryam Niamir-Fuller, Donald Gabriels, Caroline King, Friederike Knabe, Ahang Kowsar, Boshra Salem, Thomas Schaaf, Gemma Shepherd, and Richard Thomas Overcoming One of the Greatest Environmental Challenges of Our Times: Re-thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification A Policy Brief based on The Joint International Conference: “Desertification and the International Policy Imperative” Algiers, Algeria, 17-19 December, 2006 Authors: Zafar Adeel, Janos Bogardi, Christopher Braeuel, Pamela Chasek, Maryam Niamir-Fuller, Donald Gabriels, Caroline King, Friederike Knabe, Ahang Kowsar, Boshra Salem, Thomas Schaaf, Gemma Shepherd, and Richard Thomas Partners: Algerian Ministry of Land Planning and Environment Foreword ver the past few dwindling interest in addressing this issue as a Oyears, it has become full-blown global challenge. Policies, whether increasingly clear that implemented at the national or international level, desertification is one of are failing to take full account of this slow, creeping the most pressing global problem when addressing poverty and economic environmental challenges development at large. Some forces of globalization, of our time, threatening while striving to reduce economic inequality and to reverse the gains in eliminate poverty, are in actuality contributing to the sustainable development worsening desertification. Perverse agricultural subsidies that we have seen emerge are one such example. in many parts of the world. It is a process that UNU has a mission to bridge the divide between can inherently destabilize the research and policy-making communities in societies by deepening order to address pressing global challenges such as poverty and creating environmental refugees who can desertification. -

Download Global Catastrophic Risks 2020

Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES FOUNDATION (GCF) ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2020 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Ulrika Westin, editor-in-chief Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Victoria Wariaro, coordinator Weber Shandwick, creative director and graphic design. CONTRIBUTORS Kennette Benedict Senior Advisor, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Joana Castro Pereira Postdoctoral Researcher at Portuguese Institute of International Relations, NOVA University of Lisbon Philip Osano Research Fellow, Natural Resources and Ecosystems, Stockholm Environment Institute David Heymann Head and Senior Fellow, Centre on Global Health Security, Chatham House, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Romana Kofler, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs Lindley Johnson, NASA Planetary Defense Officer and Program Executive of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office Gerhard Drolshagen, University of Oldenburg and the European Space Agency Stephen Sparks Professor, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol Ariel Conn Founder and -

Global Catastrophic Risks 2017 INTRODUCTION

Global Catastrophic Risks 2017 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2017 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Carin Ism, project leader Elinor Hägg, creative director Julien Leyre, editor in chief Kristina Thyrsson, graphic designer Ben Rhee, lead researcher Erik Johansson, graphic designer Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Jesper Wallerborg, illustrator Elizabeth Ng, copywriter Dan Hoopert, illustrator CONTRIBUTORS Nobuyasu Abe Maria Ivanova Janos Pasztor Japanese Ambassador and Commissioner, Associate Professor of Global Governance Senior Fellow and Executive Director, C2G2 Japan Atomic Energy Commission; former UN and Director, Center for Governance and Initiative on Geoengineering, Carnegie Council Under-Secretary General for Disarmament Sustainability, University of Massachusetts Affairs Boston; Global Challenges Foundation Anders Sandberg Ambassador Senior Research Fellow, Future of Humanity Anthony Aguirre Institute Co-founder, Future of Life Institute Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament Tim Spahr Mats Andersson and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, CEO of NEO Sciences, LLC, former Director Vice chairman, Global Challenges Foundation Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative of the Minor Planetary Center, Harvard- for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Smithsonian -

Our Planet, Our Health, Our Future

DISCUSSION PAPER Our Planet, Our Health, Our Future Human health and the Rio Conventions: biological diversity, climate change and desertification Our Planet, Our Health, Our Future Our Planet, Our Health, Our Future Human health and the Rio Conventions: biological diversity, climate change and desertification Coordinating lead authors: Jonathan Patz1, Carlos Corvalan2, Pierre Horwitz3, Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum4 Lead authors: Nick Watts5, Marina Maiero4, Sarah Olson1,6, Jennifer Hales7, Clark Miller8, Kathryn Campbell9, Cristina Romanelli9, David Cooper9 Reviewers: Daniele Violetti10, Fernando Castellanos Silveira10, Dan Bondi Ogolla10, Grant Kirkman10, Tiffany Hodgson10, Sergio Zelaya-Bonilla11, Elena Villalobos-Prats4 1 University of Wisconsin, USA; 2 Pan-American Health Organization and World Health Organization; 3 Edith Cowan University, Australia; 4 World Health Organization; 5 The University of Western Australia, Australia; 6 Wildlife Conservation Society; 7 Independent Consultant, Reston, VA, USA; 8 Arizona State University, USA; 9 Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; 10 Secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; 11 Secretariat of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. © World Health Organization 2012 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). -

The International Crime of Ecocide the INTERNATIONAL CRIME of ECOCIDE

Gray: The International Crime of Ecocide THE INTERNATIONAL CRIME OF ECOCIDE MARK ALLAN GRAY* INTRODUCTION And I have felt A presence that disturbs me with the joy Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime Of somethingfar more deeply interfused, Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns, And the round ocean and the living air, And the blue sky, and in the mind of man ...Therefore am I still A lover of the meadows and the woods, And mountains; and of all that we behold From this green earth William Wordsworth From earliest times, humans have demonstrated a remarkable capacity to subdue and alter their physical environment. What began as a struggle for survival became a predominance among living things, then, in wealthier societies, a relentless drive for comfort and pleasure. Even, perhaps especially, in less-developed countries (LDCs), where for many survival remains a struggle, the conquest of nature proceeds apace. "Development" is now a worldwide synonym for progress.' It is therefore ironic that the scope and effects of human activity actually threaten our survival as a species. Scientists and politicians cannot agree on the precise causes and implications of, let alone solutions to, such internation- al catastrophes as ozone layer depletion, global warming and species extinction. There is nevertheless growing acceptance of the notion that arrogance, ignorance and greed, combined with overpopulation and powered by technology, are responsible for such severe resource exploitation and * LL.B. (Toronto), LL.M. (Monash). First Secretary, Australian Permanent Mission to the United Nations, New York. Former Head of the Environmental Law Unit, Legal Office, Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra. -

Drought and Desertification in Iran

hydrology Article Drought and Desertification in Iran Iraj Emadodin *, Thorsten Reinsch and Friedhelm Taube Institute for Crop Science and Plant Breeding, Group of Grass and Forage Science/Organic Agriculture, Hermann-Rodewald-Straße 9, 24118 Kiel, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-431-880-1516 Received: 1 April 2019; Accepted: 5 August 2019; Published: 7 August 2019 Abstract: Iran has different climatic and geographical zones (mountainous and desert areas), mostly arid and semi-arid, which are suffering from land degradation. Desertification as a land degradation process in Iran is created by natural and anthropogenic driving forces. Meteorological drought is a major natural driving force of desertification and occurs due to the extended periods of low precipitation. Scarcity of water, as well as the excessive use of water resources, mainly for agriculture, creates negative water balances and changes in plant cover, and accelerates desertification. Despite various political measures having been taken in the past, desertification is still a serious environmental problem in many regions in Iran. In this study, drought and aridity indices derived from long-term temperature and precipitation data were used in order to show long-term drought occurrence in different climatic zones in Iran. The results indicated the occurrence of severe and extremely severe meteorological droughts in recent decades in the areas studied. Moreover, the De Martonne Aridity Index (IDM) and precipitation variability index (PVI) showed an ongoing negative trend on the basis of long-term data and the conducted regression analysis. Rapid population growth, soil salinization, and poor water resource management are also considered as the main anthropogenic drivers. -

Desertification: the Broader Context

INVITED LECTURED Desertification: the broader context M.J. Kirkby University of Leeds (United Kingdom) ABSTRACT After over twenty years of research, there is still not complete consensus on even how to define desertification. This is reflected in the changing emphasis of UNCCD and EU programmes. The focus on physical processes in the 1990s has changed, first to an emphasis on the impacts of desertification and global change, and more recently towards sustainability rather than degradation as the core of most research effort, although much is still concerned with scenarios of possible future change. Different research tools are able to survey different windows on changing degradation status. Remote sensing methods, for example, provide an excellent window on the recent past, but little forecasting potential beyond projecting linear trends. Dynamic models add some understanding of the interaction of different components, and are increasingly engaging with socio-economic as well as strictly bio-physical processes, but are still limited by the intervention of the unexpected – the boom in biofuel demand, the credit crunch etc – that severely limit their forecasting horizons. This survey examines some of the over-arching relationships that must always constrain the relationships between population, food, land, water and energy, constraining the overall sustainability of global systems in a way that can only temporarily be ignored through irreversible mining of resources and exploitation of one region at the expense of another. The land sets constraints on food production that can partially be overcome through technological development, linked as both cause and effect to population growth, and may also be reduced by degradation. -

Climate Torts and Ecocide in the Context of Proposals for an International Environmental Court

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Climate Torts and Ecocide in the Context of Proposals for an International Environmental Court Patrick Foster CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/40 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Climate Torts and Ecocide in the Context of Proposals for an International Environmental Court Patrick Foster Graduating June, 2011 Advisor: Professor Jürgen Dedring Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ..........................................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER ONE: NECESSITY AND FEASIBILITY...................................................................................4 CAUSES OF ACTION AND THEORIES OF JUSTICE...............................................................................................5 DIPLOMATIC THEORY IN THE CONTEXT OF ENVIRONMENTAL TREATY MAKING ...........................................7 CHAPTER TWO: INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL TORTS: CLIMATE CHANGE LITIGATION .......................................................................................................................................................9