Desertification: a Visual Synthesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the Risks: International Level and 7 Integration Across Scales

Managing the Risks: International Level and 7 Integration across Scales Coordinating Lead Authors: Ian Burton (Canada), O. Pauline Dube (Botswana) Lead Authors: Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum (Switzerland), Ian Davis (UK), Richard J.T. Klein (Sweden), Joanne Linnerooth-Bayer (USA), Apurva Sanghi (USA), Ferenc Toth (Austria) Review Editors: Joy Jacqueline Pereira (Malaysia), Linda Sygna (Norway) Contributing Authors: Neil Adger (UK), Thea Dickinson (Canada), Kris Ebi (USA), Md. Tarik ul Islam (Canada / Bangladesh), Clarisse Kehler Siebert (Sweden) This chapter should be cited as: Burton, I., O.P. Dube, D. Campbell-Lendrum, I. Davis, R.J.T. Klein, J. Linnerooth-Bayer, A. Sanghi, and F. Toth, 2012: Managing the risks: international level and integration across scales. In: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation [Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, pp. 393-435. 393 Managing the Risks: International Level and Integration across Scales Chapter 7 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................396 7.1. The International Level of Risk Management..........................................................................398 -

Projected Sea Level Rise and Its Impact on Barrier Islands Along the East Coast, USA Cara Johnson Gettysburg College

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Life without the Beach: Projected Sea Level Rise and its Impact on Barrier Islands Along the East Coast, USA Cara Johnson Gettysburg College Gabrielle N. Kase Gettysburg College Samantha B. Pfeffer Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Johnson, Cara; Kase, Gabrielle N.; and Pfeffer, Samantha B., "Life without the Beach: Projected Sea Level Rise and its Impact on Barrier Islands Along the East Coast, USA" (2019). Student Publications. 707. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/707 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 707 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Life without the Beach: Projected Sea Level Rise and its Impact on Barrier Islands Along the East Coast, USA Abstract As climate change is becoming a global issue, the impact of sea level rise is increasingly becoming a threat to humans, wildlife, infrastructure, and ecosystems. To evaluate the effects of sea level rise on barrier islands and coastal regions, we studied future projections of sea level rise at Ocean City and Assateague Island, Maryland. -

Extinction Is Inevitable in the Globalized World

Extinction is inevitable in the globalized world Aishwarya Maheshwari1 1Banda University of Agriculture and Technology July 23, 2020 Abstract No abstract - Extinction is a natural process and every species on this planet has an expiration date except Homo sapiens because we are extending our expiry at the cost of other species (Brook and Alroy 2017, Pimm et al. 2014, Ceballos et al. 2015). In contrast, biodiversity loss is not natural but a global issue and it is not caused by the globalization, but as a result of human activities at the global level (Pimm et al. 2014, Ceballos et al. 2015). Eventually, severe biodiversity losses lead to anthropogenic die-off and extinction of naturally occurring species (Pimm et al. 2014, Ceballos et al. 2015, DeVos et al. 2014). The previous, current and future extinction rates have been estimated using a variety of measures and their estimation methodologies vary (to be between 100 to 10,000 times higher than the natural extinction rate) but they clearly demonstrate that current extinction rates are far above than the \background" rates (Brook and Alroy 2017, Pimm et al. 2014, Ceballos et al. 2015, DeVos et al. 2014, Lamkin and Miller 2016). Aggravatedly, population declines and extirpations are appearing to be more graving than species extinction and negative cascading consequences on ecosystem services (Ceballosa et al. 2020). Substantial information is available on over-exploitation of natural resources by humans in the globalization perspective (Ceballosa et al. 2020, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, Groom et al. 2006, Ehrnfeld 2003) and we have lost an estimated US$ 4-20 trillion per year in ecosystem services owing to land-cover change and US$ 6-11 trillion per year from land degradation during 1997 to 2011 (OECD 2019). -

Slow-Onset Processes and Resulting Loss and Damage

Publication Series ADDRESSING LOSS AND DAMAGE FROM SLOW-ONSET PROCESSES Slow-onset Processes and Resulting Loss and Damage – An introduction Table of contents L 4 22 ist of a bbre Summary of Loss and damage via tio key facts and due to slow-onset ns definitions processes AR4 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report 6 22 What is loss and damage? Introduction AR5 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report COP Conference of the Parties to the 23 United Nations Framework Convention on 9 What losses and damages IMPRINT Climate Change can result from slow-onset Slow-onset ENDA Environment Development Action Energy, processes? Authors Environment and Development Programme processes and their Laura Schäfer, Pia Jorks, Emmanuel Seck, Energy key characteristics 26 Oumou Koulibaly, Aliou Diouf ESL Extreme Sea Level What losses and damages Contributors GDP Gross Domestic Product 9 can result from sea level rise? Idy Niang, Bounama Dieye, Omar Sow, Vera GMSL Global mean sea level What is a slow-onset process? Künzel, Rixa Schwarz, Erin Roberts, Roxana 31 Baldrich, Nathalie Koffi Nguessan GMSLR Global mean sea level rise 10 IOM International Organization on Migration What are key characteristics Loss and damage Editing Adam Goulston – Scize Group LLC of slow-onset processes? in Senegal due to IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sea level rise Layout and graphics LECZ Low-elevation coastal zone 14 Karin Roth – Wissen in Worten OCHA Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs What are other relevant January 2021 terms for the terminology on 35 RCP Representative -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

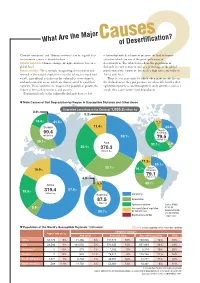

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Assessing Climate Change's Contribution to Global Catastrophic

Assessing Climate Change’s Contribution to Global Catastrophic Risk Simon Beard,1,2 Lauren Holt,1 Shahar Avin,1 Asaf Tzachor,1 Luke Kemp,1,3 Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh,1,4 Phil Torres, and Haydn Belfield1 5 A growing number of people and organizations have claimed climate change is an imminent threat to human civilization and survival but there is currently no way to verify such claims. This paper considers what is already known about this risk and describes new ways of assessing it. First, it reviews existing assessments of climate change’s contribution to global catastrophic risk and their limitations. It then introduces new conceptual and evaluative tools, being developed by scholars of global catastrophic risk that could help to overcome these limitations. These connect global catastrophic risk to planetary boundary concepts, classify its key features, and place global catastrophes in a broader policy context. While not yet constituting a comprehensive risk assessment; applying these tools can yield new insights and suggest plausible models of how climate change could cause a global catastrophe. Climate Change; Global Catastrophic Risk; Planetary Boundaries; Food Security; Conflict “Understanding the long-term consequences of nuclear war is not a problem amenable to experimental verification – at least not more than once" Carl Sagan (1983) With these words, Carl Sagan opened one of the most influential papers ever written on the possibility of a global catastrophe. “Nuclear war and climatic catastrophe: Some policy implications” set out a clear and credible mechanism by which nuclear war might lead to human extinction or global civilization collapse by triggering a nuclear winter. -

Re-Thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification

Overcoming One of the Greatest Environmental Challenges of Our Times: Re-thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification Authors: Zafar Adeel, Janos Bogardi, Christopher Braeuel, Pamela Chasek, Maryam Niamir-Fuller, Donald Gabriels, Caroline King, Friederike Knabe, Ahang Kowsar, Boshra Salem, Thomas Schaaf, Gemma Shepherd, and Richard Thomas Overcoming One of the Greatest Environmental Challenges of Our Times: Re-thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification A Policy Brief based on The Joint International Conference: “Desertification and the International Policy Imperative” Algiers, Algeria, 17-19 December, 2006 Authors: Zafar Adeel, Janos Bogardi, Christopher Braeuel, Pamela Chasek, Maryam Niamir-Fuller, Donald Gabriels, Caroline King, Friederike Knabe, Ahang Kowsar, Boshra Salem, Thomas Schaaf, Gemma Shepherd, and Richard Thomas Partners: Algerian Ministry of Land Planning and Environment Foreword ver the past few dwindling interest in addressing this issue as a Oyears, it has become full-blown global challenge. Policies, whether increasingly clear that implemented at the national or international level, desertification is one of are failing to take full account of this slow, creeping the most pressing global problem when addressing poverty and economic environmental challenges development at large. Some forces of globalization, of our time, threatening while striving to reduce economic inequality and to reverse the gains in eliminate poverty, are in actuality contributing to the sustainable development worsening desertification. Perverse agricultural subsidies that we have seen emerge are one such example. in many parts of the world. It is a process that UNU has a mission to bridge the divide between can inherently destabilize the research and policy-making communities in societies by deepening order to address pressing global challenges such as poverty and creating environmental refugees who can desertification. -

Conference Report: Arctic Warming, Deadly Dance

MURROW CENTER 2013 INTERNATIONAL INQUIRY A WITCH’S BREW ARCTIC WARMING + GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE The Arctic—at the center of the The grounding of Shell Oil’s huge security issues plaguing the region. sky-blue flag of the United Nations— ocean drilling rig during a winter Some more is required: is more a focus of governments storm in the Gulf of Alaska on New 1. An ambitious international and peoples today than ever before. Year’s Eve 2012 underscores the campaign of public awareness and This is partly because of the region’s need for more careful, even skeptical, public diplomacy to better educate abundant resources and its growing international attention rather than peoples and governments around the impact on global climate change. any posture of benign neglect world to the vital stakes involved. The mostly frigid, ice- 2. The U.S. Congress to bound Arctic is warmer sign the International now than it has been in Law of the Seas, first recorded human memory. approved in 1983 and Because of atmospheric signed by 164 countries change, the Arctic Sea’s since, to allow the U.S. temperature is rising, and to protect its sovereign the glaciers and ice packs rights in the area and are melting. The warming gain some “street cred” of the permafrost which for its concern about covers much of the environmental protection. Arctic, is unleashing long-frozen methane 3. United Nations greenhouse gases into support of the Arctic the atmosphere, thus Council to undertake compounding its effect on more rigorous regulations climate change. The mix is a witch’s brew. -

A Global Early Warning System for Pandemics Mobilizing Surveillance for Emerging Pathogens

A Global Early Warning System for Pandemics Mobilizing Surveillance for Emerging Pathogens ESTHER KROFAH, CARLY GASCA, AND ANNA DEGARMO About the Milken Institute The Milken Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank. For the past three decades, the Milken Institute has served as a catalyst for practical, scalable solutions to global challenges by connecting human, financial, and educational resources to those who need them. Guided by a conviction that the best ideas, under-resourced, cannot succeed, we conduct research and analysis and convene top experts, innovators, and influencers from different backgrounds and competing viewpoints. We leverage this expertise and insight to construct programs and policy initiatives. These activities are designed to help people build meaningful lives in which they can experience health and well-being, pursue effective education and gainful employment, and access the resources required to create ever-expanding opportunities for themselves and their broader communities. About FasterCures FasterCures, a center of the Milken Institute, is working to build a system that is effective, efficient, and driven by a clear vision: patient needs above all else. We believe that transformative and lifesaving science should be fully realized and deliver better treatments to the people who need them. ©2021 Milken Institute This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. CONTENTS -

Download Global Catastrophic Risks 2020

Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES FOUNDATION (GCF) ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2020 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Ulrika Westin, editor-in-chief Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Victoria Wariaro, coordinator Weber Shandwick, creative director and graphic design. CONTRIBUTORS Kennette Benedict Senior Advisor, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Joana Castro Pereira Postdoctoral Researcher at Portuguese Institute of International Relations, NOVA University of Lisbon Philip Osano Research Fellow, Natural Resources and Ecosystems, Stockholm Environment Institute David Heymann Head and Senior Fellow, Centre on Global Health Security, Chatham House, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Romana Kofler, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs Lindley Johnson, NASA Planetary Defense Officer and Program Executive of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office Gerhard Drolshagen, University of Oldenburg and the European Space Agency Stephen Sparks Professor, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol Ariel Conn Founder and -

Swelling Oceans: Planning for Sea Level Rise

Swelling Seas: Planning for sea level rise Westley Owers Bachelor of Town Planning Faculty of the Built Environment University of New South Wales November 2006 Abstract Emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere over the last hundreds of years have placed us in a precarious position, in that we have forced change upon one of the world’s most important systems: climate. This climate change will have devastating impacts around the world. Of all the impacts of human induced climate change, it is sea level rise that is regarded as the most certain. Sea level is expected to rise in a best case scenario of one metre by the year 2100. However, there is still uncertainty surrounding how the environment will react to greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore a sea level rise of up to six metres above current levels by the year 2100 cannot be ruled out. As sea level rises it will bring with it debilitating impacts such as inundation of coastal areas, increased coastal erosion and an increased flooding of inland areas in storm surge occurrences. The scope and magnitude of this environmental issue is such that these impacts will seriously alter human settlement and fragile ecosystems in nations throughout the world. The only way of reducing the impacts of this environmental issue is for government to prepare coastal policy and legislation to address this issue now. The extent at which the impacts of sea level rise are experienced at a local, state and national level within nations will be a direct result of the adaptive response that governments implement to address this environmental issue.