Slow-Onset Processes and Resulting Loss and Damage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

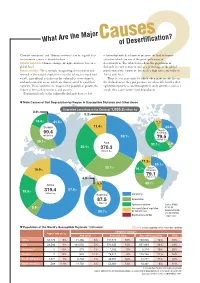

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Assessing Climate Change's Contribution to Global Catastrophic

Assessing Climate Change’s Contribution to Global Catastrophic Risk Simon Beard,1,2 Lauren Holt,1 Shahar Avin,1 Asaf Tzachor,1 Luke Kemp,1,3 Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh,1,4 Phil Torres, and Haydn Belfield1 5 A growing number of people and organizations have claimed climate change is an imminent threat to human civilization and survival but there is currently no way to verify such claims. This paper considers what is already known about this risk and describes new ways of assessing it. First, it reviews existing assessments of climate change’s contribution to global catastrophic risk and their limitations. It then introduces new conceptual and evaluative tools, being developed by scholars of global catastrophic risk that could help to overcome these limitations. These connect global catastrophic risk to planetary boundary concepts, classify its key features, and place global catastrophes in a broader policy context. While not yet constituting a comprehensive risk assessment; applying these tools can yield new insights and suggest plausible models of how climate change could cause a global catastrophe. Climate Change; Global Catastrophic Risk; Planetary Boundaries; Food Security; Conflict “Understanding the long-term consequences of nuclear war is not a problem amenable to experimental verification – at least not more than once" Carl Sagan (1983) With these words, Carl Sagan opened one of the most influential papers ever written on the possibility of a global catastrophe. “Nuclear war and climatic catastrophe: Some policy implications” set out a clear and credible mechanism by which nuclear war might lead to human extinction or global civilization collapse by triggering a nuclear winter. -

Re-Thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification

Overcoming One of the Greatest Environmental Challenges of Our Times: Re-thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification Authors: Zafar Adeel, Janos Bogardi, Christopher Braeuel, Pamela Chasek, Maryam Niamir-Fuller, Donald Gabriels, Caroline King, Friederike Knabe, Ahang Kowsar, Boshra Salem, Thomas Schaaf, Gemma Shepherd, and Richard Thomas Overcoming One of the Greatest Environmental Challenges of Our Times: Re-thinking Policies to Cope with Desertification A Policy Brief based on The Joint International Conference: “Desertification and the International Policy Imperative” Algiers, Algeria, 17-19 December, 2006 Authors: Zafar Adeel, Janos Bogardi, Christopher Braeuel, Pamela Chasek, Maryam Niamir-Fuller, Donald Gabriels, Caroline King, Friederike Knabe, Ahang Kowsar, Boshra Salem, Thomas Schaaf, Gemma Shepherd, and Richard Thomas Partners: Algerian Ministry of Land Planning and Environment Foreword ver the past few dwindling interest in addressing this issue as a Oyears, it has become full-blown global challenge. Policies, whether increasingly clear that implemented at the national or international level, desertification is one of are failing to take full account of this slow, creeping the most pressing global problem when addressing poverty and economic environmental challenges development at large. Some forces of globalization, of our time, threatening while striving to reduce economic inequality and to reverse the gains in eliminate poverty, are in actuality contributing to the sustainable development worsening desertification. Perverse agricultural subsidies that we have seen emerge are one such example. in many parts of the world. It is a process that UNU has a mission to bridge the divide between can inherently destabilize the research and policy-making communities in societies by deepening order to address pressing global challenges such as poverty and creating environmental refugees who can desertification. -

Loss and Damage to Ecosystem Services

Loss and Damage to Ecosystem Services Zinta Zommers, David Wrathall and Kees van der Geest December 2014 UNU-EHS Institute for Environment and Human Security This paper is part of a set of working papers that resulted from the Resilience Academy 2013-2014. United Nations University Institute of Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS) publishes these papers as part of its UNU-EHS Working Paper series. Series title: Livelihood Resilience in the Face of Global Environmental Change Paper title: Loss and Damage to Ecosystem Services Authors: Zinta Zommers, David Wrathall and Kees van der Geest Publication date: December 2014 This paper should be cited as: Zommers, Z., Wrathall, D. and van der Geest, K. (2014). Loss and Damage to Ecosystem Services. UNU-EHS Working Paper Series, No.2. Bonn: United Nations University Institute of Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS). Loss and Damage to Ecosystem Services Zommers, Z.1, Wrathall, D2, van der Geest, K2 1 Division of Early Warning and Assessment, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya 2 United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), Environmental Migration, Social Vulnerability and Adaptation (EMSVA), Bonn, Germany Abstract Loss and damage has risen to global attention with the establishment of the ‘Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts’. While much of the discussion has focused on loss and damage to human livelihoods, climate change is also having a significant impact on ecosystems. The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (2014) indicates that adaptation options for ecosystems may be more limited than for human systems and consequently loss and damage both to ecosystems, and to ecosystem services, may be expected. -

Ocean Acidification in Washington State

University of Washington • Washington Sea Grant Ocean Acidification in Washington State What is Ocean Acidification? OA in Washington State cean Acidification (or ‘OA’) is a long-term decrease ur region is experiencing ocean acidification sooner Oin seawater pH that is primarily caused by the Oand more severely than expected, due to a combina- ocean’s uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2 ) from the atmo- tion of human and natural causes. In the spring and sum- sphere. CO2 generated by humans’ use of fossil fuels and mer, acidification along our coast is compounded by up- deforestation has been accumulating in the atmosphere welling, which mixes deep, naturally low-pH seawater into since the industrial revolution. About one quarter of this the already acidified surface layer. In Puget Sound, nutri- CO2 is absorbed by the oceans, pH describes the acidity of a liquid ents generated by human activities (mostly where it reacts with water to form nitrogen and phosphorus from sewage, carbonic acid. As a result, the aver- fertilizers and manure) fuel processes that age pH of seawater at the ocean add even more CO2 to this ‘doubly-acidified’ surface has already dropped by ~0.1 seawater. The combination can be deadly units, a 30% increase in acidity. If to vulnerable organisms. pH levels as low atmospheric CO2 levels continue as 7.4 have been recorded in Hood Canal, to climb at the present rate, ocean an important shellfish-growing region. acidity will double by the end of this State and federal agencies, scientists, tribes, century. shellfish growers and NGOs are working together to address OA in our region. -

Download Global Catastrophic Risks 2020

Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES FOUNDATION (GCF) ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2020 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Ulrika Westin, editor-in-chief Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Victoria Wariaro, coordinator Weber Shandwick, creative director and graphic design. CONTRIBUTORS Kennette Benedict Senior Advisor, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Joana Castro Pereira Postdoctoral Researcher at Portuguese Institute of International Relations, NOVA University of Lisbon Philip Osano Research Fellow, Natural Resources and Ecosystems, Stockholm Environment Institute David Heymann Head and Senior Fellow, Centre on Global Health Security, Chatham House, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Romana Kofler, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs Lindley Johnson, NASA Planetary Defense Officer and Program Executive of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office Gerhard Drolshagen, University of Oldenburg and the European Space Agency Stephen Sparks Professor, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol Ariel Conn Founder and -

Ocean Acidification Due to Increasing Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide

Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide Policy document 12/05 June 2005 ISBN 0 85403 617 2 This report can be found at www.royalsoc.ac.uk ISBN 0 85403 617 2 © The Royal Society 2005 Requests to reproduce all or part of this document should be submitted to: Science Policy Section The Royal Society 6-9 Carlton House Terrace London SW1Y 5AG email [email protected] Copy edited and typeset by The Clyvedon Press Ltd, Cardiff, UK ii | June 2005 | The Royal Society Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide Contents Page Summary vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to the report 1 1.2 The oceans and carbon dioxide: acidification 1 1.3 Acidification and the surface oceans 2 1.4 Ocean life and acidification 2 1.5 Interaction with the Earth systems 2 1.6 Adaptation to and mitigation of ocean acidification 2 1.7 Artificial deep ocean storage of carbon dioxide 3 1.8 Conduct of the study 3 2 Effects of atmospheric CO2 enhancement on ocean chemistry 5 2.1 Introduction 5 2.2 The impact of increasing CO2 on the chemistry of ocean waters 5 2.2.1 The oceans and the carbon cycle 5 2.2.2 The oceans and carbon dioxide 6 2.2.3 The oceans as a carbonate buffer 6 2.3 Natural variation in pH of the oceans 6 2.4 Factors affecting CO2 uptake by the oceans 7 2.5 How oceans have responded to changes in atmospheric CO2 in the past 7 2.6 Change in ocean chemistry due to increases in atmospheric CO2 from human activities 9 2.6.1 Change to the oceans -

Loss and Damage: Roadmap to Relevance for the Warsaw International Mechanism

THINK TANK & RESEARCH Briefing Paper Loss and Damage: Roadmap to Relevance for the Warsaw International Mechanism – First Version – Laura Schäfer & Sönke Kreft 2 Germanwatch Brief Summary The topic of loss and damage has seen substantial advancements from Bali onwards. With the establishment of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM) in decision 2/CP. 19, loss and damage finally gets embedded institutionally within the interna- tional climate regime – providing a platform to explore and identify effective responses to climate change induced loss and damage, to expand the understanding of climate conse- quences and to find an appropriate mix of tools to address loss and damage. The Workplan for the WIM, to be elaborated by the ExCom in its initial meeting, has to ensure that the mechanism develops into a meaningful, relevant and utile institution. One way to achieve this is to structure the work into key phases (1. Understanding and needs gathering, 2. Link- ing up, 3. Leadership and facilitating approaches), building on existing outputs provided by the Work Programme on Loss and Damage in 2011-2013. Imprint Authors: Laura Schäfer & Sönke Kreft Publisher: Germanwatch e.V. Office Bonn Office Berlin Kaiserstr. 201 Stresemannstr. 72 D-53113 Bonn D-10963 Berlin Phone +49 (0) 228 60492-0, Fax -19 Phone +49 (0) 30 2888 356-0, Fax -1 Internet: http://www.germanwatch.org E-mail: [email protected] March 2014 Purchase order number: 14-2-05e This publication can be downloaded at: www.germanwatch.org/en/8366 The policy brief is an output of the Germanwatch “Klima- und Entwicklungspolitik für die be- Bread for the World Partnership sonders Verwundbaren in einer dynami- schen Welt: Kapazitätenaufbau, Allianzbildung und Politikgestaltung“ Roadmap to Relevance for the Warsaw International Mechanism 3 Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ -

9. AM Ecocide

Amendments to draft resolution On the crime of Ecocide № Party Line Action Current Text Proposed Amendment Explanation 1 Bündnis 90/ 1 replace On an international recognition of the Tackle environmental destruction: Die Grünen crime of ecocide: 2 Bündnis 90/ 25 replace that global warming must be limited to agreed to holding the increase in the global Die Grünen 1,5°C. average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognising that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change. Amendments on Draft Resolution on an international recognition of the crime of ecocide European Green Party - 5th Congress, Liverpool, UK, 30 March-2 April 2017 1 № Party Line Action Current Text Proposed Amendment Explanation 3 Vihreät - De 30-36 delete According to environmental scientists Not necessary for making the point, Gröna Johan Rockström (Stockholm Resilience the chapter draws the attention Centre) and Will Steffen (Australian away from the point of the National University), these are two among resolution making it unnecessarily four “planetary boundaries” that have long. 4 Strana 30-36 replace already been exceeded. These “planetary These present two out of nine “planetary The original text presents the zelenych boundaries” involve nine thresholds on boundaries”, or nine thresholds on core concept of "planetary boundaries" (Czech core environmental issues (greenhouse gas environmental issues, beyond which human only as an opinion of Rockstrom Greens) amount in atmosphere, biodiversity, but existence would be threatened. The concept and Steffen and, moreover, it does also ocean acidification, land use for crop, has been introduced by a group of not state any source, that this consumption of freshwater...) beyond international scientists, led by Johan opinion is based on. -

Global Catastrophic Risks 2017 INTRODUCTION

Global Catastrophic Risks 2017 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2017 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Carin Ism, project leader Elinor Hägg, creative director Julien Leyre, editor in chief Kristina Thyrsson, graphic designer Ben Rhee, lead researcher Erik Johansson, graphic designer Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Jesper Wallerborg, illustrator Elizabeth Ng, copywriter Dan Hoopert, illustrator CONTRIBUTORS Nobuyasu Abe Maria Ivanova Janos Pasztor Japanese Ambassador and Commissioner, Associate Professor of Global Governance Senior Fellow and Executive Director, C2G2 Japan Atomic Energy Commission; former UN and Director, Center for Governance and Initiative on Geoengineering, Carnegie Council Under-Secretary General for Disarmament Sustainability, University of Massachusetts Affairs Boston; Global Challenges Foundation Anders Sandberg Ambassador Senior Research Fellow, Future of Humanity Anthony Aguirre Institute Co-founder, Future of Life Institute Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament Tim Spahr Mats Andersson and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, CEO of NEO Sciences, LLC, former Director Vice chairman, Global Challenges Foundation Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative of the Minor Planetary Center, Harvard- for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Smithsonian -

Ocean Acidification and the Permo- Triassic Mass Extinction: Process and Manifestation

Goldschmidt2015 Abstracts Ocean acidification and the permo- Triassic mass extinction: Process and manifestation S. A. KASEMANN1, R. WOOD2*, M. O. CLARKSON3, T. M. LENTON4, S. J. DAINES4, S. RICHOZ5, F. OHNEMUELLER1, A. MEIXNER1, S. W. POULTON6 AND E. T. TIPPER7 1Department of Geosciences & MARUM-Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, Univ. of Bremen, Germany 2School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, UK (*[email protected]) 3Department of Chemistry, Univ. of Otago, New Zealand 4College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Univ. of Exeter 5Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Graz, Austria 6School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK 7Dept. of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, UK Ocean acidification triggered by Siberian Trap volcanism was a possible kill mechanism for the Permian-Triassic Boundary (PTB) mass extinction, but direct evidence for an acidification event is lacking. We present a high resolution seawater pH record across this interval, utilizing boron isotope data (δ11B) combined with petrographic analysis and a quantitative modeling approach. Through this integration we are able to produce an envelope that encompasses the most realistic range in pH, which then allows us to resolve three distinct chronological phases of carbon cycle perturbation, each with very different environmental consequences for the Late Permian-Early Triassic Earth system. In the latest Permian, increased ocean alkalinity, primed the Earth system with a low level of atmospheric CO2 and a high ocean buffering capacity. The first phase of extinction was coincident with a slow injection of carbon into the atmosphere and ocean pH remained stable. During the second extinction pulse, however, a rapid and large injection of carbon caused an abrupt acidification event that drove the preferential loss of heavily calcified marine biota.