Torso-Notes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interview with Sergio Martino: an American in Rome

1 An interview with Sergio Martino: An American in Rome Giulio Olesen, Bournemouth University Introduction Sergio Martino (born Rome, 1938) is a film director known for his contribution to 1970s and 1980s Italian filone cinema. His first success came with the giallo Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (Next!) (1971), from which he moved to spaghetti westerns (Mannaja [A Man Called Blade], 1977), gialli (I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale [Torso], 1973), poliziotteschi (Milano trema: la polizia vuole giustizia [The Violent Professionals], 1973), horror movies (La montagna del dio cannibale [The Mountain of the Cannibal God], 1978; L’isola degli uomini pesce [Island of Mutations], 1979), science fiction movies (2019, dopo la caduta di New York [2019, After the Fall of New York], 1983) and comedies (Giovannona Coscialunga disonorata con onore [Giovannona Long-Thigh], 1973). His works witness the hybridization of international and local cinematic genres as a pivotal characteristic of Italian filone cinema. This face-to-face interview took place in Rome on 26 October 2015 in the venues premises of Martino’s production company, Dania Film, and addresses his horror and giallo productions. Much scholarship analyses filone cinema under the lens of cult or transnational cinema studies. In this respect, the interview aims at collecting Martino’s considerations regarding the actual state of debate on Italian filone cinema. Nevertheless, e Emphasis is put on a different approach towards this kind of cinema; an approach that aims at analysing filone cinema for its capacity to represent contemporaneous issues and concerns. Accordingly, introducing Martino’s relationship with Hollywood, the interview focuses on the way in which his horror movies managed to intercept register fears and neuroses of Italian society. -

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985 By Xavier Mendik Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985, By Xavier Mendik This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Xavier Mendik All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5954-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5954-7 This book is dedicated with much love to Caroline and Zena CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Foreword ................................................................................................... xii Enzo G. Castellari Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Bodies of Desire and Bodies of Distress beyond the ‘Argento Effect’ Chapter One .............................................................................................. 21 “There is Something Wrong with that Scene”: The Return of the Repressed in 1970s Giallo Cinema Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

Le Commedie Sexy All’Italiana Girate In

| 1 LE COMMEDIE SEXY ALL’ITALIANA GIRATE IN ABRUZZO CHE SALVARONO IL CINEMA IN CRISI di Piercesare Stagni* L’AQUILA – La “commedia sexy” nasce intorno alla metà degli anni Settanta come www.virtuquotidiane.it | 2 sottogenere del filone principale della commedia all’italiana: in quel periodo il cinema viveva nel nostro paese una profonda crisi di spettatori e si corse quindi ai ripari cercando nuove idee. Questo nuovo genere fondeva l’erotismo con la comicità ed era ispirato ai personaggi lanciati in quegli anni da Lando Buzzanca e Carlo Giuffrè, efficacissimi rappresentanti di quel “maschio italico” che spesso consolava le vedove inconsolabili. La novità era la presenza contemporanea nelle storie di diverse categorie di interpreti: l’attore brillante principale, il comico di spalla a cui affidare battute più o meno grevi e ovviamente l’immancabile bomba erotica. Era nata la commedia sexy, con registi come Sergio Martino, Michele Massimo Tarantino, Nando Cicero, Mariano Laurenti e tutta la loro schiera di improbabili ed audaci “dottoresse”, “insegnanti”, “liceali”, “professoresse”, “cameriere”, “soldatesse”, “infermiere” e “poliziotte”. Tra gli attori come non citare Lino Banfi, Renzo Montagnani, Aldo Maccione, Mario Carotenuto, tra i comici ovviamente Alvaro Vitali e Gianfranco D’Angelo, con le dive sexy la memoria va subito ad Edwige Fenech, Annamaria Rizzoli, Nadia Cassino, Barbara Bouchet, Pamela Miti, Lilli Carati, Carmen Russo, Carmen Villani. Nel 1981 ben tre di queste pellicole, che, non dimentichiamolo mai, salvarono per anni il cinema italiano dal disastro con i loro incassi stellari, furono girate quasi completamente in Abruzzo: La maestra di sci, C’è un fantasma nel mio letto e Bollenti spiriti. -

Westerns…All'italiana

Issue #70 Featuring: TURN I’ll KILL YOU, THE FAR SIDE OF JERICHO, Spaghetti Western Poster Art, Spaghetti Western Film Locations in the U.S.A., Tim Lucas interview, DVD reviews WAI! #70 The Swingin’ Doors Welcome to another on-line edition of Westerns…All’Italiana! kicking off 2008. Several things are happening for the fanzine. We have found a host or I should say two hosts for the zine. Jamie Edwards and his Drive-In Connection are hosting the zine for most of our U.S. readers (www.thedriveinconnection.com) and Sebastian Haselbeck is hosting it at his Spaghetti Westerns Database for the European readers (www.spaghetti- western.net). Our own Kim August is working on a new website (here’s her current blog site http://gunsmudblood.blogspot.com/ ) that will archive all editions of the zine starting with issue #1. This of course will take quite a while to complete with Kim still in college. Thankfully she’s very young as she’ll be working on this project until her retirement 60 years from now. Anyway you can visit these sites and read or download your copy of the fanzine whenever you feel the urge. Several new DVD and CD releases have been issued since the last edition of WAI! and co-editor Lee Broughton has covered the DVDs as always. The CDs will be featured on the last page of each issue so you will be made aware of what is available. We have completed several interviews of interest in recent months. One with author Tim Lucas, who has just recently released his huge volume on Mario Bava, appears in this issue. -

“I Should Not Have Come to This Place”: Complicating Ichabod‟S Faith

“I SHOULD NOT HAVE COME TO THIS PLACE”: COMPLICATING ICHABOD‟S FAITH IN REASON IN TIM BURTON‟S SLEEPY HOLLOW A Project Paper Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By JOEL KENDRICK FONSTAD Keywords: film, adaptation, rationality, reason, belief, myth, folktale, horror, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, The Pit and the Pendulum, La Maschera del Demonio Copyright Joel Kendrick Fonstad, November 2010. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this project in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this project in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my project work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my project work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this project or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my project. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this project paper in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i ABSTRACT Tim Burton‟s films are largely thought to be exercises in style over content, and film adaptations in general are largely thought to be lesser than their source works. -

Descargar Catálogo 2017

PLATAFORMA: FINANCIA FUNDADORA Y ORGANIZADORA PRODUCE INVITAN ALIADOS PRINCIPALES AUSPICIADORES OFICIALES PATROCINAN AUSPICIADORES MEDIA PARTNERS MEDIOS COLABORADORES COLABORADORES DIRAC Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores Gobierno de Chile Palabras 09 Words FILMS DE Film de Apertura 22 INAUGURACIÓN & Opening Feature CLAUSURA Film de Clausura 26 OPENING & CLOSING FILMS Closing Feature P. 22 Selección Oficial 28 EN COMPETENCIA Largometraje Internacional Official International IN COMPETITION Feature Selection P. 27 Selección Oficial 43 Largometraje Chileno Official Chilean Feature Selection Selección Oficial 53 Cortometraje Latinoamericano Official Latin American Short Film Selection Selección Oficial Cortometraje Infantil Latinoamericano FICVin FICVin Official Latin American 67 Children’s Short Film Selection CINEASTAS Sion Sono 75 INVITADOS Deborah Stratman 85 GUEST Socavón Cine FILMAKERS 92 P. 74 MUESTRA HOMENAJES MUESTRA RETROSPECTIVA PARALELA TRIBUTES RETROSPECTIVE SERIES OUT OF COMPETITION Alice Guy 102 La Lección de Cine 229 PROGRAM Lotte Reiniger 113 The Film Lesson Clásicos 232 P. 101 Maya Deren 121 Classics Colectivo del 126 Cabo Astica Totalmente Salvaje 236 Private Astica’s Collective Totally Wild Claudio Arrau 133 Vhs Erótico 239 Víctor Jara 137 Erotic Vhs 50 años 141 Wavelength MUESTRA UACH Wavelength 50 Years UACH PROGRAM La Gran Ola de Tokio 146 Muestra Facultad de 243 The Great Tokyo Wave Filosofía y Humanidades Espadas Voladoras: 156 Philosophy and Humanities School El Wuxia Taiwanés Program Flying Swords: Taiwanese Wuxia Muestra Facultad de 246 Giallo: Terror a la 166 Arquitectura y Arte Uach Italiana UACH Arquitecture and Arts Faculty Program MUESTRA DE CINE MUESTRA INFANTIL FICVin CONTEMPORANEO FICVin CHILDREN’S PROGRAM CONTEMPORARY CINEMA SERIES CINEMAS 261 Gala 176 CINEMAS Gala Nuevos Caminos 186 INDUSTRIA New Pathways INDUSTRY Disidencias 197 Dissidences P. -

“We're Not Rated X for Nothin', Baby!”

CORSO DI DOTTORATO IN “LE FORME DEL TESTO” Curriculum: Linguistica, Filologia e Critica Ciclo XXXI Coordinatore: prof. Luca Crescenzi “We’re not rated X for nothin’, baby!” Satire and Censorship in the Translation of Underground Comix Dottoranda: Chiara Polli Settore scientifico-disciplinare L-LIN/12 Relatore: Prof. Andrea Binelli Anno accademico 2017/2018 CONTENTS CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 1: FROM X-MEN TO X-RATED ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 1. “DEPRAVITY FOR CHILDREN – TEN CENTS A COPY!” ......................................................... 12 1.1. A Nation of Stars and Comic Strips ................................................................................................................... 12 1.2. Comic Books: Shades of a Golden Age ............................................................................................................ 24 1.3. Comics Scare: (Self-)Censorship and Hysteria ................................................................................................. 41 Chapter 2. “HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN?”: RISE AND FALL OF A COUNTERCULTURAL REVOLUTION ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Tutti I Segreti Della Suspense

LA NOSTRA DOMENICA 41 DOMENICA 1 FEBBRAIO Home Video 2009 Musical italiano Noir milanese Sexy nostrano Mina e Celentano Un Calibro di culto Fenech da giovane Io bacio tu baci Milano Calibro 9 Giovannona Regia di Piero Vivarelli Regia: Fernando Di Leo Coscialunga… Con Mina, Adriano Celentano, Interpreti: Gastone Moschin, Regia: Sergio Martino Mario Carotenuto, Umberto Barbara Bouchet, Mario Adorf. Interpreti: Edwige Fenech, Orsini Italia, 1972 Pippo Franco, Gigi Ballista Italia, 1961 - Surf Video Nocturno/RaroVideo Italia, 1973 - Aegida/Sony ***Cecchi Gori **** ** SESSANTA Piero Vivarelli, tra il ’60 e il ’61, dirige i due Da un racconto di Scerbanenco, forse il Il titolo, da completarecon…disonora- più grandi talenti del beat italiano - Mina e miglior noir italiano di sempre, un film ta con onore, è fra i più proverbiali del E SETTANTA Celentano - in due film, Sanremo la grande d’azione e d’atmosfera degno della grande sexy anni ’70. Visto il tema (un industria- Alberto Crespi sfida e Io bacio tu baci. Il primo è un «musi- serieB hollywoodiana.Le musiche (di Baca- le inquinatore assume una prostituta carello» classico, questo ha un sottotesto an- love degli Osanna)contribuiscono a uncul- per corrompere un giudice) potrebbe ti-capitalista tutt’altro che banale. Spuntano to che ha in Quentin Tarantino uno degli essere rivalutato come precursore di anche Peppino Di Capri e Tony Renis. «adepti». Edizione ottima, con ricchi extra. Vallettopoli. precedenti precettori, arriva alle Suspense estreme conseguenze. Regia di Jack Clayton Questo breve racconto gotico ha Con Deborah Kerr, Martin Stephens, Pamela dato luogo a una serie «infinita» di in- Franklin terpretazioni e adattamenti. -

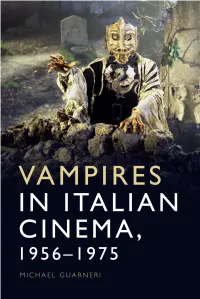

9781474458139 Vampires in It

VAMPIRES IN ITALIAN CINEMA, 1956–1975 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd i 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iiii 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM VAMPIRES IN ITALIAN CINEMA, 1956–1975 Michael Guarneri 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iiiiii 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Michael Guarneri, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/12.5 pt Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5811 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5813 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5814 6 (epub) The right of Michael Guarneri to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iivv 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM CONTENTS Figures and tables vi Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 PART I THE INDUSTRIAL CONTEXT 1. The Italian fi lm industry (1945–1985) 23 2. Italian vampire cinema (1956–1975) 41 PART II VAMPIRE SEX AND VAMPIRE GENDER 3. -

Download October 2013 Movie Schedule

Movie Museum OCTOBER 2013 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY Hawaii Premiere! NOBODY TO WATCH CYBORG SHE IRON MAN 3 THIS IS THE END SOMETHING FOR (2013-US) OVER ME (2008-Japan) (2013-US) in widescreen EVERYONE Japanese w/Eng subtitles, ws in widescreen 12:00, 4:15 & 8:30pm only (1970-US) (2008-Japan) with Robert Downey Jr., Japanese w/Eng subtitles, ws 12:00 & 6:15pm only ------------------------------------ 12:00, 4:15 & 8:30pm only ------------------------------------ Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Kingsley, Hawaii Premiere! ------------------------------------ 12, 2 & 6:30pm only Don Cheadle, Guy Pearce. ------------------------------------ THIS IS THE END NOBODY TO WATCH Hawaii Premiere! CYBORG SHE (2013-US) in widescreen Directed by Shane Black. OVER ME Satyajit Ray Double Feature! (2008-Japan) with Seth Rogen, James (2008-Japan) THE COWARD (1965-India) Japanese w/Eng subtitles, ws Franco, Jonah Hill. 12:00, 2:15, 4:30, 6:45 Japanese w/Eng subtitles, ws DELIVERANCE (1984-India) 2:00 & 6:15pm only 2:00 & 6:15pm only 4:15 & 8:45pm only 3 2:15, 4:15 & 8:30pm only4 & 9:00pm 567 2 by Georges Franju! MUCH ADO ABOUT EYES WITHOUT A FACE SOMETHING FOR MUCH ADO ABOUT BEHIND THE (1960-France/Italy) EVERYONE NOTHING CANDELABRA NOTHING French w/Eng subtitles, w.s (1970-US) (2012-US) in widescreen (2013-US) in widescreen (2012-US) in widescreen Pierre Brasseur, Alida Valli. with Angela Lansbury. Directed by Joss Whedon. Michael Douglas, Matt Damon Directed by Joss Whedon. 12:00, 3:30 & 7:00pm only 12:00, 3:45 & 7:30pm only 12:30, 4:30 & 8:30pm only 12:00, 2:15, 4:30 & 6:45pm 12:30 & 8:45pm ------------------------------------ ------------------------------------ ------------------------------------ ------------------------------------ ------------------------------------ JUDEX THE CONSEQUENCES CYBORG SHE EYES WITHOUT A FACE BEHIND THE (1963-France/Italy) OF LOVE (2008-Japan) (1960-France/Italy) CANDELABRA French w/Eng subtitles, w.s (2004-Italy) Japanese w/Eng subtitles, ws French w/Eng subtitles, w.s (2013-US) in widescreen Channing Pollock, Edith Scob. -

EDWIGE FENECH (Edwige Sfenek) Filmografia Essenziale Dal 1968 Al 1975

EDWIGE FENECH (Edwige Sfenek) Filmografia essenziale dal 1968 al 1975 ANNO TITOLO TITOLO ORIGINALE REGIA VOTO 1968 IL FIGLIO DI AQUILA NERA IDEM JAMES REED 6,5 1968 SAMOA - REGINA DELLA GIUNGLA IDEM JAMES REED 6 1968 SUSANNA E I SUOI DOLCI VIZI ALLA CORTE DEL RE FRAU WEIRTIN HAT AUCH EINEN GRAFEN FRANZ ANTEL 1969 ALLE DAME DEL CASTELLO PIACE MOLTO FARE... KOMM, LIEBE MAID UND MACHE JOSEF ZACHAR 5 1969 DESIDERI, VOGLIE PAZZE DI TRE INSAZIABILI... ALLE KATZCHEN NASCHEN GERN JOZEF ZACHAR 6 1969 MIA NIPOTE...LA VERGINE MADAME UND IHRE NICHTE EBERHARD SCHROEDER 1969 I PECCATI DI MADAME BOVARY IDEM JOHN SCOTT 5 1969 TESTA O CROCE IDEM PIERO PIEROTTI 5 1969 TOP SENSATION IDEM OTTAVIO ALESSI 6,5 1969 IL TRIONFO DELLA CASTA SUSANNA FRAU WIRTIN HAT AUCH EINE NICHTE FRANZ ANTEL 6,5 1969 L' UOMO DAL PENNELLO D' ORO DER MANN MIT DEM GOLDENEN PINSEL FRANZ MARISCHKA 5 1970 5 BAMBOLE PER LA LUNA D' AGOSTO IDEM MARIO BAVA 7 1970 DON FRANCO E DON CICCIO NELL' ANNO... IDEM MARINO GIROLAMI 6,5 1970 LE MANS - SCORCIATOIA PER L' INFERNO IDEM RICHARD KEAN 6 1970 SATIRICOSISSIMO IDEM MARIANO LAURENTI 6,5 1971 LE CALDE NOTTI DI DON GIOVANNI IDEM AL BRADLEY 6,5 1971 DESERTO DI FUOCO IDEM RENZO MERUSI 1971 LO STRANO VIZIO DELLA SIGNORA WARDH IDEM SERGIO MARTINO 7 1972 LA BELLA ANTONIA, PRIMA MONICA E POI DIMONIA IDEM MARIANO LAURENTI 5,5 1972 PERCHE` QUELLE STRANE GOCCE DI SANGUE... IDEM ANTHONY ASCOTT 6,5 1972 QUANDO LE DONNE SI CHIAMAVANO MADONNE IDEM ALDO GRIMALDI 6,5 1972 QUEL GRAN PEZZO DELL' UBALDA TUTTA NUDA.. -

Jugend Medienschutz-Report

Jugend Medien Schutz-Report 2/07 Fachzeitschrift zum Jugendmedienschutz mit Newsletter April 2007 Inhaltsverzeichnis Heftmitte/Beihefter: Aktuelle Entscheidungen im April 2007 AUFSÄTZE / BERICHTE (INDIZIERUNGEN / BESCHLAGNAHMEN) 2 Christiane Pröhl: Beschwerdeflut beim Werberat – Mehr Eingaben gegen weniger Werbekampagnen 3 Dirk Nolden: KJM-Test zeigt: Jugendschutzfilter genügen INDIZIERUNGS-LISTEN bisher nicht den gesetzlichen Anforderungen 4 Jörg Weigand: Vom Leihbuchschreiber zum Bestsellerautor: 13 Listenteile A und B (gem. § 18 Abs. 2 Nr. 1, 2 JuSchG) Heinz G. Konsalik – Ein Autorenporträt sowie sog. Liste E (Einträge vor dem 01.04.2003) 13 1. Filme (Videos/DVDs/Laser-Disks): 2958 STATISTIKEN 35 2. Spiele (Computer-/Video-/Automatenspiele): 476 2 Beschwerdestatistik 2006 des Deutschen Werberates 39 3. Printmedien (Bücher/Broschüren/Comics etc.): 224 10 Jahresstatistik 2006 der Bundesprüfstelle (BPjM) 42 4. Tonträger (Schallplatten/CDs/MCs): 650 RECHTSPRECHUNG 48 Listenteile C und D (gem. § 18 Abs. 2 Nr. 3, 4 JuSchG) 65 BGH, Urteil vom 15.03.07, Az.: 3 StR 486/06: Durchgestrichenes Hakenkreuz kein verbotenes Kenn- 48 5. Telemedien zeichen nach § 86 a StGB – Nichtöffentliche Listenteile, daher kein Abdruck – 68 VG München, Beschluss vom 31.01.2007, Az.: M 17 S 07.144: Pornographische Angebote im Internet ohne wirksame Zugangsbeschränkung BESCHLAGNAHME-LISTE 72 OLG Celle, Beschluss vom 13. Februar 2007, 48 6. Sonderübersicht Az.: 322 Ss 24/07: Unzulässige Posendarstellung von beschlagnahmter/eingezogener Medien: 601 Kindern und Jugendlichen im Internet Regelmäßige Anordnungsgründe/Straftatbestände: • Volksverhetzung, §§ 86a, 130, 130a StGB KURZNACHRICHTEN • Gewaltverherrlichung, § 131 StGB 5 BGH: Durchgestrichenes Hakenkreuz kein verbotenes • harte Pornographie, §§ 184a, 184b StGB Kennzeichen ◆ BGH: Forenbetreiber haften für fremde Beiträge ab Kenntnis ◆ Holocaust-Leugner Rudolf ver- ◆ SONDERÜBERSICHTEN urteilt ULR/HAM: Neue Medienanstalt hat Arbeit auf- genommen ◆ Bei Europas größter Schülerplattform steht 55 7.