Editor's Column: the Polyphony Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

English Polyphony and the Roman Church David Greenwood

caec1 1a English Polyphony and the Roman Church David Greenwood VOLUME 87, NO. 2 SUMMER, 1960 . ~5 EIGHTH ANNUAL LITURGICAL MUSIC WORKSHOP Flor Peeters Francis Brunner Roger Wagner Paul Koch Ermin Vitry Richard Schuler August 14-26, 1960 Inquire MUSIC DEPARTMENT Boys Town, Nebraska CAECILIA Published four times a year, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Second-Class Postage Paid at Omaha, Nebraska. Subscription price--$3.00 per year All articles for publication must be in the hands of the editor, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska, 30 days before month of publication. Business Manager: Norbert Letter Change of address should be sent to the circulation manager: Paul Sing, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska Postmaster: Form 3579 to Caecilia, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebr. CHANT ACCOMPANIMENTS by Bernard Jones KYRIE XVI " - .. - -91 Ky - ri - e_ * e - le -i - son. Ky - ri - e_ e - le - i - son •. " -.J I I I I J I I J I j I J : ' I I I " - ., - •· - - Ky-ri - e_ e - le -i - son. Chri-ste_ e - le -i - son. Chi-i-ste_ e - le- i - son.· I ( " .., I I j .Q. .0. I J J ~ ) : - ' ' " - - 9J Chri - ste_ e - le - i - son. Ky - ri - e __ e - le - i - son. " .., j .A - I I J J I I " - ., - . Ky -ri - e_ e - le - i - son. Ky- ri - e_* e -le - i - son. " I " I I I ~ I J I I J J. _J. J.,.-___ : . T T l I I M:SS Suppkmcnt to Caecilia Vol. 87, No. 2 SANCTUS XVI 11 a II I I I 2. -

Sound and Place at Central Public Squares in Belo Horizonte (Brazil)

Invisible Places 18–20JULY 2014, VISEU, PORTUGAL Polyphony of the squares: Sound and Place at Central Public Squares in Belo Horizonte (Brazil) Luiz Henrique Assis Garcia [email protected] Professor at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil Pedro Silva Marra [email protected] Phd candidate at Universidade Federal Fluminense,Belo Horizonte, Brazil Abstract This article aims to understand and compare the use of sounds and music as a tool to disput- ing, sharing and lotting space in two squares in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. In order to do so, citizens manipulate sounds and their parameters, such as intensity, frequency and spatiality. We refer to research data collected by Nucleurb/CCNM-UFMG constituted by a set of methodological procedures that involve field observation, sound recording, photo- graphs, field notesand research on archives, gathering and cross analyzing texts, pictures and sounds, in order to grasp the dynamics of conformation of “place” within the urban space. Keywords: Sonorities, Squares, Urban Space provisional version 1. Introduction A street crier screams constantly, as pedestrians pass by him, advertising a cellphone chip store’s services. During his intervals, another street crier asks whether people want to cut their hair or not. On the background, a succession of popular songs are played on a Record store, and groups of friends sitting on benches talk. An informal math teacher tries to sell a DVD in which he teaches how to solve fastly square root problems. The other side of the square, beyond the crossing of two busy avenues, Peruvian musicians prepare their con- cert, connecting microfones and speakers through cables, as street artists finish their circus presentation. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PRISMS and POLYPHONY

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PRISMS AND POLYPHONY: THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF HIGH SCHOOL BAND STUDENTS AND THEIR DIRECTOR AS THEY PREPARE FOR AN ADJUDICATED PERFORMANCE Stephen W. Miles Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 Dissertation directed by: Professor Francine Hultgren Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership College of Education University of Maryland This hermeneutic phenomenological inquiry is called by the question: What are the lived experiences of high school band students and their director as they prepare for an adjudicated performance? While there are many lenses through which the phenomenon of music preparation and music making has been explored, a relatively untapped aspect of this phenomenon is the experience as lived by the students themselves. The experiences and behaviors of the band director are so inexorably intertwined with the student experience that this essential contextual element is also explored as a means to understand the phenomenon more fully. Two metaphorical constructs – one visual, one musical – provide a framework upon which this exploration is built. As a prism refracts a single color of light into a wide spectrum of hues, views from within illumine a variety of unique perspectives and uncover both divergent and convergent aspects of this experience. Polyphony (multiple contrasting voices working independently, yet harmoniously, toward a unified musical product) enables understandings of the multiplicity of experiences inherent in ensemble performance. Conversations with student participants and their director, notes from my observations, and journal offerings provide the text for phenomenological reflection and interpretation. The methodology underpinning this human science inquiry is identified by Max van Manen (2003) as one that “involves description, interpretation, and self-reflective or critical analysis” (p. -

June 1918) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1918 Volume 36, Number 06 (June 1918) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 36, Number 06 (June 1918)." , (1918). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/647 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE JUNE 1918 THE ETUDE Page 361 Prepare Now More Corns than Ever Putting a Chinese Wall Around Your But They Do Not Stay” The Story That Millions Tell FOR NEXT SEASON THIS is not a way to prevent corns. That Educational Opportunities would mean no dainty slippers, no close- fitting shoes. And that would be worse than corns. | Order Teaching Material Early Our plea is to end corns as soon as they appear. Do it in a gentle, scientific way. Do it easily, quickly, completely, by apply¬ Protest Against an Enormously Increased Tax Abundant Reasons and Convincing Argu¬ ing a Blue-jay plaster. ments can be Advanced in Favor of this Modern footwear creates more corns than ever. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

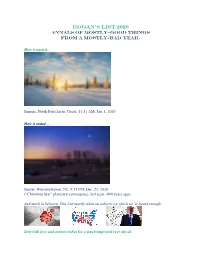

Rogan's List 2020

Rogan’s List 2020 Annals of mostly-good things from a mostly-bad year. How it started… Sunrise, North Pole/Arctic Circle, 11:11 AM, Jan. 1, 2020 How it ended… Sunset, Winston-Salem, NC, 5:11 PM, Dec. 21, 2020 (“Christmas Star” planetary convergence, last seen ~800 years ago). And much in between. This List mostly silent on subjects on which we’ve heard enough. Sent with love and ardent wishes for a much-improved year ahead. 2020 Books: Fiction 22. Ernest Cline, Ready Player Two. Fans of original (me, yep) will thrill to the story continued. 21. Curtis Sittenfield, Rodham. Brilliant conceit—Hillary spurns Bill, her/America’s future unspools much differently—runs out of steam over latter third, but ‘A’ for imagination. 20. Carl Hiaasen, Squeeze Me. Signature madcap Hiaasen/S-Florida joint, topically timely. 19. Jeanine Cummins, American Dirt. Riveting & violent borderland tale. 18. Lily King, Writers & Lovers. “I have a pact with myself not to think about money in the morning.” Heroine(ish) Casey wonderfully drawn; reminder that Gen Xers had ¼-life crises too. 17. Cara Black, Three Hours in Paris. 2nd-best thriller of a year when escapism mattered most. 16. Chip Schorr, The After. Best thriller—and by a newcomer to the genre, no less! 15. Jill McCorkle, Hieroglyphics. Dean of NC storytellers centers her latest on—a storied house. 14. Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Mexican Gothic. After Untamed Shore, her best work. 13. Richard Ford, Sorry For Your Trouble. Bard of New Jersey’s stories; not a clinker in the lot. 12. Tola Rotimi Abraham, Black Sunday. -

History of Barbershop

HISTORY OF BARBERSHOP By David Krause and David Wright Definition of barbershop harmony. Read: Definition of Barbershop Harmony, from the Forward of the Contest and Judging Handbook. The Purpose Of This Course. We will attempt to trace the roots and the evolution of barbershop harmony from well before its actual beginnings up to the present. We will try to answer these questions: What were the tides of history which spawned the birth of the barbershop quartet, and what environment allowed this style of music to flourish? What were its musical forerunners? What are its defining characteristics? What other types of music were fostered contemporaneously, and how did they influence the growth of quartet singing? Which styles are similar, and how are they similar? How did the term "barbershop" arise? How long did the historical era of the barbershop quartet last? What other kinds of music sprang forth from it? Why did the style eventually need preservation? How was SPEBSQSA formed, and how did it become a national movement? What other organizations have joined the cause? How have they coped with the task of preservation? Are current day efforts still on course in preserving the style? How has the style changed since the Society was formed? We will spend the next few hours contemplating and attempting to answer these questions. Overtones. As barbershoppers, we are very conscious of the "ringing" effect which complements our singing. We consider it our reward for singing well- defined pitches in tune. The fact that a tone produced by a voice or an instrument is accompanied by a whole series of pitches in addition to the fundamental one which our ear most easily detects has been known for centuries. -

Religare Arts Initiative Ltd. 7 Atmaram Mansion, Level 1, Scindia House, K

Religare arts initiative Ltd. 7 Atmaram Mansion, Level 1, Scindia House, K. G. Marg, CP, New Delhi - 110001 T + 91-11-43727000 / 7001 email: [email protected] website: www.religarearts.com Religare arts initiative presents the an exhibition showcasing works created by the resident artists of the Curated by Sumakshi Singh and Paola Cabal 2010 Connaught Place: The WhyNot Place residency programme Tuesday 10th August - Tuesday 31st August, 2010 during the months of June and July, 2010 Artwork by Raffaella Della Olga Qutub Minar, Devi Art Foundation Direct Connect Direct Connect Talk: Ravi Agarwal, Paola Cabal Talk: Vivan Sundaram, Sumakshi Singh NGMA Dinner at Sumakshi’s Khoj Opening Slide show - Sumakshi 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Field Trip, Connaught Place - led by Gagandeep Singh Direct Connect Old Mehrauli walk Talk: Atul Bhalla - led by Sohail Hashmi Old Delhi, Shajahanabad Sarai Foundation Opening - led by Atul Bhalla Open Studio Night Purnna Behera Brad Biancardi Becky Brown Rebecca Carter The 2010 WhyNot Place Summer Residency Programme at arts.i Raffaella Della Olga Garima Jayadevan The Transforming State 2010 Greg Jones Kavita Singh Kale Table of Contents 20 Purnna Behera by Sumakshi Singh 84 Megha Katyal by Sumakshi Singh Megha Katyal Nidhi Khurana 28 Brad Biancardi by Sumakshi Singh 92 Nidhi Khurana by Paola Cabal Jitesh Malik Koustav Nag [front end-pages] Residency Activities June 36 Becky Brown by Paola Cabal 100 Jitesh Malik by Paola Cabal Rajesh Kr Prasad 9 The Religare -

AMS/SMT Milwaukee 2014 Abstracts Thursday Afternoon

AMS/SMT American Musicological Society Society for Music Theory Program & Abstracts & Abstracts Program 2014 Milwaukee Milwaukee 6-9 November 2014 Abstracts g Abstracts of Papers Read at the American Musicological Society Eightieth Annual Meeting and the Society for Music Theory Thirty-seventh Annual Meeting 6–9 November 14 Hilton Hotel and Wisconsin Center Milwaukee, Wisconsin g AMS/SMT 2014 Annual Meeting Edited by Judy Lochhead and Richard Will Chairs, 14 SMT and AMS Program Committee Local Arrangements Committee Mitchell Brauner, Chair, Judith Kuhn, Rebecca Littman, Timothy Miller, Timothy Noonan, Gillian Rodger Performance Committee Catherine Gordon-Seifert, Chair, Mitchell Brauner, ex officio, David Dolata, Steve Swayne Program Committees AMS: Richard Will, Chair, Suzanne Cusick, Daniel Goldmark, Heather Hadlock, Beth E. Levy, Ryan Minor, Alejandro Planchart SMT: Judy Lochhead, Chair, Poundie Burstein, ex officio, Michael Klein, Sherry Lee, Alexander Rehding, Adam Ricci, Leigh VanHandel The AMS would like to thank the following people and organizations for their generous support: Calvary Presbyterian Church, Milwaukee Joan Parsley Charles Sullivan and Early Music Now Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Program and Abstracts of Papers Read (ISSN 9-1) is published annually for the An- nual Meeting of the American Musicological Society and the Society for Music Theory, where one copy is distributed to attendees free of charge. Additional copies may be purchased from the American Musicological Society for $1. per copy plus $. U.S. shipping and handling (add $. shipping for each additional copy). For international orders, please contact the American Musicological Society for shipping prices: AMS, 61 College Station, Brunswick ME 411-41 (e-mail [email protected]). -

Table of Contents

iv Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................ i Mani Shekhar Singh Editorial ......................................................................................................... ii Dikshit Bhagabati, Malini Chidambaram, Neeta Stephen A Lexicon of Law and Listening ..................................................................... 2 James Parker The Dreaming, Never to be Lost .................................................................. 24 Upendra Baxi Indian Necropolitics and Weaponizing Covid-19 in Kashmir ...................... 78 Ather Zia Hopeful Rantings of a Dalit-Queer Person ................................................... 91 Dhiren Borisa Queerings .................................................................................................... 97 Oishik Sircar Writing Against the Violence of History ..................................................... 103 Shals Mahajan The Ineffable Somethingness of Love and Revolution ................................. 108 Rahul Rao “But No One Gets Used to Living Here” ..................................................... 113 Jordy Rosenberg The Ministry for the Unconsoled ................................................................ 123 Arundhati Roy Seasons of Life and Seasons of Law .............................................................. 129 Dolly Kikon Pandemic Diary in Three Parts.................................................................... 140 Vasuki Nesiah Where -

Inventory of Genealogy Rm ( 8324).Xls

0 2015 - Inventory of Genealogy Rm ( 8324).xls Author/ Compiler/ Editor / Year # Index Subject Bk # in series / Notes TITLE ASHTABULA COUNTY SORTED by Title Subject Author / Yr Pub TITLE Index BK ASH CO # 001 1883 Ashtabula Colony to Kansas - BK ASH CO # 002 1973 Samuel Hendry “Register of His Papers” 1807 – 1911 Index By: Pat L. Smyth BK ASH CO # 003 1975 Volunteer Fire Service in Ashtabula County, Growth & - Development By: William E. Loomis BK ASH CO # 004 2003 Merchants, Tradesmen & Manufacturers; Financial - Conditions - Ashtabula County 1921 By: Jan and Naomi McPeek (Original in Archives - Copied for Genealogy ) BK ASH CO # 005 Ashtabula County Miscellaneous News - BK ASH CO # 006 Ohio Historical Review Featuring Ashtabula County - BK ASH CO # 007 Early Years – Ashtabula Chapter 0624 Index BK ASH CO # 008 Ex-Slaves & Early Black Settlers in Ashtabula County Index BK ASH CO # 009 Ashtabula County Tool Chest - BK ASH CO # 010 - Historical Collections of Ohio, Ashtabula County Only - BK ASH CO # 011 1993 Charley Garlick “Black Strings” – “Underground - Railroad” By: Sandra Westfall BK ASH CO # 012 - Ashtabula Township Governments - taken from the internet BK ASH CO # 013 Artists with Ashtabula County Connections, Index working before 1900 BK ASH CO # 014 Ashtabula County Pioneer Association Index BK ASH CO # 015 2003 Ashtabula County Roads, by Name or Number - BK ASH CO # 016 1968 Salute To The Industry of Ashtabula County - BK ASH CO # 017 Business Review of Ashtabula County 1887 - BK ASH CO # 018 Ashtabula County – Indian Lore by