History of Barbershop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

A MESSAGE from NATIONAL PRESIDENT HAL STAAB Every Member of Our Society Should Be Interested in the Requests, and Close Co'operation with All Chapters

E l\ R B E S II 0 P The Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop !!(uartet Singing in America, [nc. SEPTEMBER, 1942 VOL. 2 CARROLL P. ADAMS. National Secretary-Treasurer. 50 Fairwood Blvd., Pleasant Ridge. Mich. NO. 1 A MESSAGE FROM NATIONAL PRESIDENT HAL STAAB Every member of our Society should be interested in the requests, and close cO'operation with all chapters. (I plans that have been formulated by our National Officers am glad to state that the national office has already and Board of Directors. These plans in reality form a been established in Detroit with Immediate Past Pres· comprehensive program for the development of our poten· ident Carroll Adams as our Executive Secretary. tialities, which if carried through, cannot help but make Chapter Secretaries will receive full information on our Society a thoroughly national 1942-43 NATIONAL PRESIDENT reports this month, and com' organization and a potent force in munications and requests are the life of our great democracy. now receiving immediate atten' We have suffered from growing tion.) pains. An inherent love for barber· 2-To issue a quality quarterly shop harmony that seems to be publication that we will all broadspread in the United States, want to read. has caused us to grow in spite of The quarterly chapter activo the fact that up to now our na' ities reports will form the basis tional set·up has been inadequate to for much of the publication. It handle the situation. We have will be replete with interesting reached a point in our history photographs, and one feature when it is imperative that we will be a page on "Barber Shop , create order out of chaos, that we Harmony". -

Music Educator's Guide & Songbook

MUSIC EDUCATOR’S GUIDE & SONGBOOKIncludes: Barbershop Harmony Teaching Guide, Seven RoyaltyFree Songs, Barbershop Tags, and Accompanying Learning CD 2014 SPEBSQSA, Inc. 110 7th Ave. No., Nashville, TN 37203-3704, USA. Tel. (800) 876-7464 Permission granted to reproduce for personal and educational use only. Commercial copying, hiring, and lending is prohibited. www.barbershop.org #209532 Dear Music Educator: Thank you for your interest in Barbershop Harmony—one of the truly American musical art foorms! I think you will be surprised at the depth of instructional material and opportunities the Barbershop Harmony Society offers. More importantly, you’ll be pleased with the way your students accept this musical style. This guide contains a significant amount of information aboutt the barbershop style, as well as many helpful suggestions on how to teach it to your students. The songs included in this guide are an introduction to the barbershop style and include a part-predominant learning CD, all of which may be copied at no extra charge. For more barbershop music, our Harmony Marketplace offers thousands of barbershop arrangements, including PDF and mp3 demos, at www.barbershop.org/arrangementts. Songbooks, manuals, part-predominant learning CDs, educational videos and DVDs, merchandise, and more can be found at www.harmonymarketplace.com. For those who are not familiar with the Society or if you would like further information, please feel free to contact us at 1-800-876-SING or at [email protected]. Thanks again for your interest in the -

The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 Nominees Are in

The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 Nominees Are In ... Kanye West Leads The Pack With Nine Nominations As Hip-Hop's Crowning Night Returns to Atlanta on Saturday, October 10 and Premieres on BET Tuesday, October 27 at 8:00 p.m.* NEW YORK, Sept.16 -- The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 nominations were announced earlier this evening on 106 & PARK, along with the highly respected renowned rapper, actor, screenwriter, film producer and director Ice Cube who will receive this year's "I AM HIP-HOP" Icon Award. Hosted by actor and comedian Mike Epps, the hip-hop event of the year returns to Atlanta's Boisfeuillet Jones Civic Center on Saturday, October 10 to celebrate the biggest names in the game - both on the mic and in the community. The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 will premiere Tuesday, October 27 at 8:00 PM*. (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20070716/BETNETWORKSLOGO ) The Hip-Hop Awards Voting Academy which is comprised of journalists, industry executives, and fans has nominated rapper, producer and style aficionado Kanye West for an impressive nine awards. Jay Z and Lil Wayne follow closely behind with seven nominations, and T.I. rounds things off with six nominations. Additionally, BET has added two new nomination categories to this year's show -- "Made-You-Look Award" (Best Hip Hop Style) which will go to the ultimate trendsetter and "Best Hip-Hop Blog Site," which will go to the online site that consistently keeps hip-hop fans in the know non-stop. ABOUT ICE CUBE Veteran rapper, Ice Cube pioneered the West Coast rap movement back in the late 80's. -

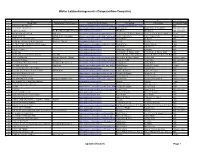

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

1St First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern

1st First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern. arr. Ozzie Westley (1944) BPC The Barberpole Cat Program and Song Book. (1987) BB1 Barber Shop Ballads: a Book of Close Harmony. ed. Sigmund Spaeth (1925) BB2 Barber Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1940) CBB Barber Shop Ballads. (Cole's Universal Library; CUL no. 2) arr. Ozzie Westley (1943?) BC Barber Shop Classics ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1946) BH Barber Shop Harmony: a Collection of New and Old Favorites For Male Quartets. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1942) BM1 Barber Shop Memories, No. 1, arr. Hugo Frey (1949) BM2 Barber Shop Memories, No. 2, arr. Hugo Frey (1951) BM3 Barber Shop Memories, No. 3, arr, Hugo Frey (1975) BP1 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 1. (1946) BP2 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 2. (1952) BP Barbershop Potpourri. (1985) BSQU Barber Shop Quartet Unforgettables, John L. Haag (1972) BSF Barber Shop Song Fest Folio. arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1948) BSS Barber Shop Songs and "Swipes." arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1946) BSS2 Barber Shop Souvenirs, for Male Quartets. New York: M. Witmark (1952) BOB The Best of Barbershop. (1986) BBB Bourne Barbershop Blockbusters (1970) BB Bourne Best Barbershop (1970) CH Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle (1936) CHR Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle. Revised (1941) CH1 Close Harmony: Male Quartets, Ballads and Funnies with Barber Shop Chords. arr. George Shackley (1925) CHB "Close Harmony" Ballads, for Male Quartets. (1952) CHS Close Harmony Songs (Sacred-Secular-Spirituals - arr. -

2018 FWD President Craig Hughes INSIDE: Conventions • Moh • Lou Laurel • Camp Fund 2 X Match • 2018 Officer Reports Ray S

Westunes Vol. 68 No. 1 Spring 2018 2018 FWD President Craig Hughes INSIDE: Conventions • MoH • Lou Laurel • Camp Fund 2 x Match • 2018 Officer Reports Ray S. Rhymer, Editor • Now in his 17th year EDITORIAL STAFF Editor in Chief Northeast Division Editor Ray S. Rhymer [email protected] Roger Perkins [email protected] Marketing & Advertising Northwest Division Editor David Melville [email protected] Don Shively [email protected] Westags Newsletter Southeast Division Editor Jerry McElfresh [email protected] Greg Price [email protected] Arizona Division Editor Southwest Division Editor Bob Shaffer [email protected] Justin McQueen [email protected] Westunes Vol. 68 No. 1 Features Spring 2018 2018 Spring Convention Remembering Lou Laurel International Quartet Preliminary Contest, Southeast A Past International President and Director of & Southwest Division Quartet and Chorus Contests, two different International Champion chapters is 3 and the FWD High School Quartet Contest. 8 remembered by Don Richardson. 2018 Arizona Division Convention 2018 Harmony Camp Celebrating the 75th year of Barbershop in Mesa, AZ Hamony Camp will be held again in Sly Park, CA with with Harmony Platoon, AZ Division Quartet and Chorus Artistic License and Capitol Ring assisting. Tell the 4 & Harmony Inc. Chorus Contests & AFTERGLOW. 9 young men in your area about it. 2018 NE & NW Division Convention Lloyd Steinkamp Endowment Fund Northeast and Northwest Division Quartet and Cho- A major donor stepped up to “double” match 5 rus Contests in Brentwood, CA, a new location. 10 contributions in 2018. 2017 Int’l Champion Masters of Harmony Marketing Wisely on a Shoe-String Budget A Masters of Harmony update after winning their first David Melville brings a different view of marketing - gold medal in San Francisco in 1990 and their ninth in you may rethink your procedures after reading this 6 Las Vegas in 2017 .. -

Four Rascals Story

GradyGrady Kerr’sKerr’s PreservationPreservation ProjectProject The Lost Quartet Series MastersMasters ofof MischiefMischief See Page 9 The Preservation Project Lost Quartet Series October 2016 TheThe PreservationPreservation ProjectProject is published as a continuation and adaptation of the award winning magazine, PRESERVATION, created by Barbershop Historian Grady Kerr. It is our goal to promote, educate, and pay tribute to those who came before and made it possible for us to enjoy the close harmony performed by thousands of men and women today. Your Preservation Crew Society Historian / Researcher / Writer / Editor / Layout Our sincere thanks to the following people Grady Kerr who helped gather information in this issue: [email protected] Don Dobson Patient Proofreaders & Fantastic Fact Checkers Jimmy & Lois Vienneau Ann McAlexander Haley Vienneau Bob Sutton Fran & Sheila Page Nancy Hertz Ellis Bobby & Kathy Pierce Lisa Spirito Graphic Supervisor Production Supervisor Steve Spirito Bruce Checca Leo Larivee Terry Clarke Rich Knapp All articles herein, unless otherwise credited, are written by the editor and do not necessarily reflect the opinions Jim Bader of the Barbershop Harmony Society, any District, any historian, any barbershopper, the BHS HQ Staff , Richard Millard Jr. or the EDITOR. Ken Thomas Daniel Costello Carl Hancuff Did you see Bob Franklin our last issue Harlan Wilson on the Norm Mendenhall Jax of Joe Schlesinger Harmony? Bob Sutton Leo Larivee READ IT Elizabeth Davies HERE James Given Curtis Terry Eddie Holt Lorin May PRESERVATION Tom Emmert John Scott Crawford Online! Robert Kelly All past 23 issues of PRESERVATION Robert Disney are available for FREE Guy Haas Ryan Iorio 2 The Preservation Project Lost Quartet Series October 2016 The TRUETRUE Story Behind the FoundingTRUETRUE of S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. -

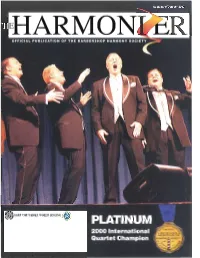

~Keep the Wiiole World Singing

~ KEEP THE WIIOLE WORLD SINGING (i) The 2000 Intemational Chorus and Quartet Contests..... Videos, Cassettes and Compact Discs. Order now and save!! tttM'~ 'tv1 tM'ketp1..c«:.e- Stock # Item Description Qty Each Total SPEBSQSA, Inc. 4652 2000 Quartet Cassette $11.95 6315 Harmony Lane 4653 2000 Chorus Cassette $11.95 Kenosha. WI 53143-5199 order both· save $4.00 (800) 876-7464 Pax: (262) 654-5552 4654 2000 Quartet CD $14.95 Delivery in time for Christmas giving in 4655 2000 Chorus CD $14.95 2000. order both - save $5.00 4165 2000 VHS Quartet Video $24.95 Please ship my order to: 4166 2000 VHS Chorus Video $24.95 Name, _ order both· save $5.00 4118 2000 *PAL Quartet Video $30.00 Sireel _ 4119 2000 *PAL Chorus Video $30.00 City _ order both· save $10.00 Total for merchandise SlalelProv ZIP _ 5% Sales Tax (Wis. residents only) Subtotal SPEBSQSA membership no. _ Shipping and handling (see below) Chapler name & no. _ Total Amount enclosed US FUNDS ONLY Use yOll MBNA America credit card! *pAL (European Formal) !,YISA.,! ..... PackClges set" to separate (ufdresses require separate pOS/(lge. Please mId: Credit card cuslomers only: US Dnd Canadian shipments Foreign shipments (your card wifl be charged /Jrior to the anticipated 56.00 shipping and handling charge $15.00 overseas shipping and handling charge de/il'el)' date) Please charge my _ Mastercard _Visa Account No. Expires _ Soptomborl Oclobor 2000 T VOLUME EHARMONl~R LX NUMBER • : f • •• ••• • 5 THE SMOOTH TRANSFER OF POWER. Exhausted from their year as champs, FRED graciously passes the title to PLATINUM. -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

Flee SOC Iely for the PRESERVATION and ENCOURAGEMENT of ~ARBER SHOP QUARTET SINGING in AMERICA, INC

JUNE, 1950 VOL. IX No. 4 DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF BARBER SHOP QUARTET HARMONY OMAHA Published By 12 t h flEe SOC IElY FOR THE PRESERVATION AND ENCOURAGEMENT ANNUAL UNE 7-11 CONVENTION OF ~ARBER SHOP QUARTET SINGING IN AMERICA, INC, IN TUIC ICCIIC III IlI.InIC TUC D. A DD.CDCUnD U AD AAnll.lV rCII.ITCD nc TL.lC WnDI n "THE 1950 REVIEW OF ARMY QUARTETS" 1", s. Arm~ lwt":o;onnd (·"t·rywhl'l"l' h'ls taken to barlwr!>hop harmony. For additional picIures of Army C\ uart~lS and choruses see inside back cover. THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION AND ENCOURAGEMENT Or BARBER SHOP QUARTET SINGING IN AMERICA. INC. VOLUME IX NO.4 JUNE. 1950 OMAHA WELCOMES S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. GEN'L CHAIRMAN "SONGS FOR MEN OMAHA MEDAL WINNERS VOL. III" TO APPEAR TO BE HEARD OVER CLARE WILSON SAYS, "RED CARPET IS OUT" The 1950 edition of "SONGS FOR MUTUAL NET MEN" should prove to have a little A transcription of the Medalist Int'I Vice-president and Convention bit of just about everything for just Contest at Omaha Saturday General Chairman Clare Wilson, of about everybody. night, June 10th, will be broad Omaha, reports that even the beef-on cast over the l\'Iutual Network the~hoof in the Omaha stockyards bellow in harmony these days. Like Of a standard, patriotic nature de~ Sunday Night, June 11th from sig:led for use by chapter choruses and 10:30 to 11 :00 P.M., Eastern all the rest of the Omahans they've Daylight Saving Time. -

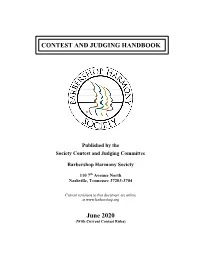

Contest and Judging Handbook

CONTEST AND JUDGING HANDBOOK Published by the Society Contest and Judging Committee Barbershop Harmony Society 110 7th Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37203-3704 Current revisions to this document are online at www.barbershop.org June 2020 (With Current Contest Rules) Ed. Note: This is a complex document with a lot of content. Please help with the challenging job of managing it by advising of any typos, incorrect references, broken hyperlinks, or suggestions for improvement. Send a note to [email protected] with page number and suggestion. Thank you! Approved by the Society Contest and Judging Committee. Published: 25 June 2020 Contest Rules, Chapter 3, contains all rules approved/authorized by the Society Board of Directors, CEO, and SCJC through 25 June 2020. TABLE OF CONTENTS (Click on chapter title or page number for direct link.) Table of Contents (06/25/20) ............................................................................................. 1-1 Definition of the Barbershop Style (8/19/18) ................................................................... 2-1 Contest Rules (6/25/20) ...................................................................................................... 3-1 The Judging System (10/25/19) ......................................................................................... 4-1 Music Category Description (2/11/20) .............................................................................. 5-1 Performance Category Description (1/19/20) .................................................................