Towards a New Lexicon of Fear: a Quantitative and Grammatical Analysis of Pertimescere in Cicero Emma Vanderpool Monmouth College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin Literature

Latin Literature By J. W. Mackail Latin Literature I. THE REPUBLIC. I. ORIGINS OF LATIN LITERATURE: EARLY EPIC AND TRAGEDY. To the Romans themselves, as they looked back two hundred years later, the beginnings of a real literature seemed definitely fixed in the generation which passed between the first and second Punic Wars. The peace of B.C. 241 closed an epoch throughout which the Roman Republic had been fighting for an assured place in the group of powers which controlled the Mediterranean world. This was now gained; and the pressure of Carthage once removed, Rome was left free to follow the natural expansion of her colonies and her commerce. Wealth and peace are comparative terms; it was in such wealth and peace as the cessation of the long and exhausting war with Carthage brought, that a leisured class began to form itself at Rome, which not only could take a certain interest in Greek literature, but felt in an indistinct way that it was their duty, as representing one of the great civilised powers, to have a substantial national culture of their own. That this new Latin literature must be based on that of Greece, went without saying; it was almost equally inevitable that its earliest forms should be in the shape of translations from that body of Greek poetry, epic and dramatic, which had for long established itself through all the Greek- speaking world as a common basis of culture. Latin literature, though artificial in a fuller sense than that of some other nations, did not escape the general law of all literatures, that they must begin by verse before they can go on to prose. -

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate from the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate From the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty By Jessica J. Stephens A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, chair Professor Bruce W. Frier Professor Richard Janko Professor Nicola Terrenato [Type text] [Type text] © Jessica J. Stephens 2016 Dedication To those of us who do not hesitate to take the long and winding road, who are stars in someone else’s sky, and who walk the hillside in the sweet summer sun. ii [Type text] [Type text] Acknowledgements I owe my deep gratitude to many people whose intellectual, emotional, and financial support made my journey possible. Without Dr. T., Eric, Jay, and Maryanne, my academic career would have never begun and I will forever be grateful for the opportunities they gave me. At Michigan, guidance in negotiating the administrative side of the PhD given by Kathleen and Michelle has been invaluable, and I have treasured the conversations I have had with them and Terre, Diana, and Molly about gardening and travelling. The network of gardeners at Project Grow has provided me with hundreds of hours of joy and a respite from the stress of the academy. I owe many thanks to my fellow graduate students, not only for attending the brown bags and Three Field Talks I gave that helped shape this project, but also for their astute feedback, wonderful camaraderie, and constant support over our many years together. Due particular recognition for reading chapters, lengthy discussions, office friendships, and hours of good company are the following: Michael McOsker, Karen Acton, Beth Platte, Trevor Kilgore, Patrick Parker, Anna Whittington, Gene Cassedy, Ryan Hughes, Ananda Burra, Tim Hart, Matt Naglak, Garrett Ryan, and Ellen Cole Lee. -

Caesar's Legion: the Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion

CAESAR’S LEGION : THE EPIC SAGA OF JULIUS CAESAR’S ELITE TENTH LEGION AND THE ARMIES OF ROME STEPHEN DANDO-COLLINS John Wiley & Sons, Inc. flast.qxd 12/5/01 4:49 PM Page xiv ffirs.qxd 12/5/01 4:47 PM Page i CAESAR’S LEGION : THE EPIC SAGA OF JULIUS CAESAR’S ELITE TENTH LEGION AND THE ARMIES OF ROME STEPHEN DANDO-COLLINS John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Copyright © 2002 by Stephen Dando-Collins. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authoriza- tion through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158-0012, (212) 850-6011, fax (212) 850-6008, email: [email protected]. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. This title is also available in print as ISBN 0-471-09570-2. -

The Lives of the Caesars

The Lives of the Caesars Suetonius The Lives of the Caesars Table of Contents The Lives of the Caesars...........................................................................................................................................1 Suetonius........................................................................................................................................................2 The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius................................................................................................3 The Lives of the Caesars—The Deified Augustus.......................................................................................23 The Lives of the Caesars—Tiberius.............................................................................................................53 The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula....................................................................................................72 The Lives of the Caesars: Claudius..............................................................................................................89 The Lives of the Caesars: Nero..................................................................................................................105 The Lives of the Caesars: Galba................................................................................................................124 The Lives of the Caesars: Otho..................................................................................................................131 -

Matthew W. Dickie, Magic and Magicians in the Greco-Roman World

MAGIC AND MAGICIANS IN THE GRECO- ROMAN WORLD This absorbing work assembles an extraordinary range of evidence for the existence of sorcerers and sorceresses in the ancient world, and addresses the question of their identities and social origins. From Greece in the fifth century BC, through Rome and Italy, to the Christian Roman Empire as far as the late seventh century AD, Professor Dickie shows the development of the concept of magic and the social and legal constraints placed on those seen as magicians. The book provides a fascinating insight into the inaccessible margins of Greco- Roman life, exploring a world of wandering holy men and women, conjurors and wonder-workers, prostitutes, procuresses, charioteers and theatrical performers. Compelling for its clarity and detail, this study is an indispensable resource for the study of ancient magic and society. Matthew W.Dickie teaches at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He has written on envy and the Evil Eye, on the learned magician, on ancient erotic magic, and on the interpretation of ancient magical texts. MAGIC AND MAGICIANS IN THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD Matthew W.Dickie LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in hardback 2001 by Routledge First published in paperback 2003 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 2001, 2003 Matthew W.Dickie All rights reserved. -

Repertoire of Characters in Roman Comedy: New Classification Approaches

GRAECO-LATINA BRUNENSIA 19, 2014, 2 ŠÁRKA HURBÁNKOVÁ (MASARYK UNIVERSITY, BRNO) REPERTOIRE OF CHARACTERS IN ROMAN COMEDY: NEW CLASSIFICATION APPROACHES What is Roman comedy? Which ancient theatre forms can be included under this term? How to classify the characters of palliatae, togatae, atellanae and mimi, having mostly complete texts of Plautus’s and Terence’s palliatae available on the one hand, and palliatae, togatae, atellanae and mimi preserved only fragmentally on the other? This study presents a method of classifying a repertoire of characters in Roman comedy which I used in my disserta- tion. Complete texts were analyzed in terms of contrasts and correspondences, allowing me to determine the correspondences and similarities not only among dramatic characters or types separately in Plautus’s and separately in Terence’s comedies, but also point out certain correspondences and similarities in the entire historical corpus of texts mapping a specific period or genre. Therefore, I determined structural functions of individual types and their roles in the corpus of texts, which, at the same time, provided me with a summary of typical traits of various types of characters, manifested in antagonism or cooperation with other types of characters. I compared this set of “words-signs” with words describing the characters from fragments, using clear arrangement into contingency tables. Due to this comparison and other partial findings enabled by this method and tools used, it was possible to describe, at least partially, not only a repertoire of characters of individual comic forms, but also compare them with each other and determine how the “dramatis personae” of Ro- man comedy changed diachronically. -

Suetonius the Life of Julius Caesar Translated By

SUETONIUS THE LIFE OF JULIUS CAESAR TRANSLATED BY ALEXANDER THOMSON, M.D. REVISED AND CORRECTED BY T. FORESTER, ESQ., A.M. ________________________________________ VITA DIVI IULI [* Numbers in parentheses indicate the pagination of the English translation.] PREFACE C. Suetonius Tranquillus was the son of a Roman knight who commanded a legion, on the side of Otho, at the battle which decided the fate of the empire in favour of Vitellius. From incidental notices in the following History, we learn that he was born towards the close of the reign of Vespasian, who died in the year 79 of the Christian era. He lived till the time of Hadrian, under whose administration he filled the office of secretary; until, with several others, he was dismissed for presuming on familiarities with the empress Sabina, of which we have no further account than that they were unbecoming his position in the imperial court. How long he survived this disgrace, which appears to have befallen him in the year 121, we are not informed; but we find that the leisure afforded him by his retirement, was employed in the composition of numerous works, of which the only portions now extant are collected in the present volume. Several of the younger Pliny's letters are addressed to Suetonius, with whom he lived in the closest friendship. They afford some brief, but generally pleasant, glimpses of his habits and career; and in a letter, in which Pliny makes application on behalf of his friend to the emperor Trajan, for a mark of favour, he speaks of him as "a most excellent, honourable, and learned man, whom he had the pleasure of entertaining under his own roof, and with whom the nearer he was brought into communion, the more he loved him." [1] The plan adopted by Suetonius in his Lives of the Twelve Caesars, led him to be more diffuse on their personal conduct and habits than on public events. -

Histo Ry: Legio XIIII GM V

Legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix Cohors I Batavorum Cohors I Hamiorum Via Romana Caesar's Fourteenth Legion. Legio XIIII, the fourteenth legion, was probably estab- lished by Gaius Iulius Caesar in 57 BC to replace recent losses during the war in Gaul before continuing the offensive against the Belgae. Caesar certainly implies the existence of a fourteenth legion in his account of the battle against another Gallic tribe, the Nervii. It is highly likely, although not readily attested, that Legio XIIII continued to play an active part in Caesar’s conquests up to the end of 54 BC. In the winter of 54/53BC, the previously pacified Eburones, a Germanic speaking tribe living between the river Meuse and the Rhenus (river Rhein), revolted against the Roman presence. The Eburones, led by Ambiorix who had been in receipt of great gifts from Gaius Iulius Caesar, attacked and destroyed Legio XIIII and five newly-enrolled cohorts encamped in their territory near Tongres. The legates, Titurius Sabinus and Arunculeius Cotta, made the mistake of leaving the safety of their encampment and the Roman garri- son, some 7,000 men, was all but annihilated. The Aquilifer of Legio XIIII saved the unit’s eagle standard from immediate capture by hurling it over the ramparts of the Roman camp, just before he was cut down. The resistance was to no avail, for that night all the remaining legionary survivors committed suicide. In the winter of the following season, 53/52BC, the newly-formed Legio XIIII, under the command of Quintus Cicero [the brother of the orator], was attacked in its winter quarters by a large contingent of marauding Germanic cavalry. -

Volker Washington 0250E 10346.Pdf (1.510Mb)

©Copyright 2012 Jaime Volker Caesarian Conflict: Portrayals of Julius Caesar in narratives of civil war Jaime Volker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Alain Gowing, Chair James J. Clauss Catherine Connors Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Classics University of Washington Abstract Caesarian Conflict: Portrayals of Julius Caesar in narratives of civil war Jaime Volker Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Alain Gowing Department of Classics This dissertation investigates the poignancy of civil war for Rome in the late Republican through early Imperial period, as focalized through depictions of Julius Caesar and, to a more limited degree, the Caesar-like Catiline. My comparative examination of Sallust’s Bellum Catilinae, Velleius Paterculus’ Historiae, and Lucan’s Pharsalia centers on how each author treats qualities and catchwords found in Caesar’s self-portrait in the Bellum Civile. By reading each portrayal of Caesar against the general’s own account of civil war, I contend that one finds shifts in issues and traits according to their relevance to an author’s own times, aims, and view of the relationship between Republic and Principate. Moreover, I suggest that whether an author portrays Julius Caesar in a positive or negative light is likely a consequence of his view of the current “Caesar” (i.e., Octavian, Tiberius, or Nero). TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Caesar on Caesar and Civil War ............................................................................... 1 0.1 Julius Caesar, the man himself? ............................................................................................ 1 0.2 The scope of this study .......................................................................................................... 5 0.3 Past scholarship .................................................................................................................. -

Ketan Ramakrishnan's Lit Notes, Expanded

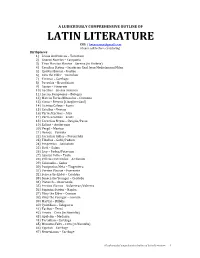

A LUDICROUSLY COMPREHENSIVE OUTLINE OF LATIN LITERATURE KHR / [email protected] Please ask before circulating. Birthplaces 1) Livius Andronicus – Tarentum 2) Gnaeus Naevius – Campania 3) Titus Maccius Plautus – Sarsina (in Umbria) 4) Caecilius Statius – Insubrian Gaul from Mediolanum/Milan 5) Quintus Ennius – Rudiae 6) Cato the Elder – Tusculum 7) Terence – Carthage 8) Pacuvius – Brundisium 9) Accius – Pisaurum 10) Lucilius – Suessa Aurunca 11) Lucius Pomponius – Bologna 12) Marcus Furius Bibaculus – Cremona 13) Cinna – Brescia (Cisapline Gaul) 14) Licinius Calvus – Rome 15) Catullus – Verona 16) Varro Atacinus – Atax 17) Varro Reatinus – Reate 18) Cornelius Nepos – Ostiglia/Pavia 19) Sallust – Amiternum 20) Vergil – Mantua 21) Horace – Venusia 22) Cornelius Gallus – Forum Iulii 23) Tibullus – Gabii/Pedum 24) Propertius – Assissium 25) Ovid – Sulmo 26) Livy – Padua/Patavium 27) Asinius Pollo – Teate 28) Velleius Paterculus – Aeclanum 29) Columella – Gades 30) Pomponius Mela – Tingentera 31) Verrius Flaccus – Praeneste 32) Seneca the Elder – Cordoba 33) Seneca the Younger – Cordoba 34) Plutarch – Chaeroneia 35) Persius Flaccus – Volaterrae/Volterra 36) Papinius Statius – Naples 37) Pliny the Elder – Comum 38) Pliny the Younger – Comum 39) Martial – Bilbilis 40) Quintilian – Calagurris 41) Tacitus – Terni 42) Fronto – Cirta (in Numidia) 43) Apuleius – Madaura 44) Tertullian – Carthage 45) Minucius Felix – Cirta (in Numidia) 46) Cyprian – Carthage 47) Nemesianus – Carthage A Ludicrously Comprehensive Outline of Latin Literature 1 48) Arnobius -

Dio's Rome an Historical Narrative Originally Composed in Greek

Dio's Rome An Historical Narrative Originally Composed in Greek During the Reigns of Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla, Macrinus, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus; And Now Presented in English Form. Second Volume Extant Books 36-44 (B.C. 69-44). Cassius Dio The Project Gutenberg EBook of Dio's Rome, by Cassius Dio This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Dio's Rome An Historical Narrative Originally Composed in Greek During the Reigns of Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla, Macrinus, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus; And Now Presented in English Form. Second Volume Extant Books 36-44 (B.C. 69-44). Author: Cassius Dio Release Date: March 17, 2004 [EBook #11607] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DIO'S ROME *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Jayam Subramanian and PG Distributed Proofreaders DIO'S ROME AN HISTORICAL NARRATIVE ORIGINALLY COMPOSED IN GREEK DURING THE REIGNS OF SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS, GETA AND CARACALLA, MACRINUS, ELAGABALUS AND ALEXANDER SEVERUS: AND Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. NOW PRESENTED IN ENGLISH FORM BY HERBERT BALDWIN FOSTER, A.B. (Harvard), Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins), Acting Professor of Greek in Lehigh University SECOND VOLUME _Extant Books 36-44 (B.C. 69-44)_. 1905 PAFRAETS BOOK COMPANY TROY NEW YORK VOLUME CONTENTS Book Thirty-six Book Thirty-seven Book Thirty-eight Book Thirty-nine Book Forty Book Forty-one Book Forty-two Book Forty-three Book Forty-four DIO'S ROMAN HISTORY 36 Metellus subdues Crete by force (chapters 1, 2)[1] Mithridates and Tigranes renew the war (chapter 3). -

A History of Roman Literature, but Inas¬ Hilarius

^ - 7X/ZVra'XWP - V* ^ ■ , *, ^ V1 * ■A a ■>- * *5 2*. •* ^ C>v ■* , 'ismjr+r \ N V ' 0 a y o * x * A> C A^ 0>V v - - '<* ■ «,% .,0* *C°JL ^% ,%* 1 ^ a p oox r WvVs^ * V **•, * 'Zr ■>” .# % \ * *Vflf,v- ^ A * ' *r i?/, *,% - S' ■* ^ =>' ° 1 A> ^ ° V/ \vv> c. -, !* * P ^ ^ - \- A A * : A \ ss A o, ft ft ,\\ « V I « z, AV■ **/%"*1 >'.<• -st»<% v *• , / / . ■>* V a /T\ ''*■' v^ -1 ^ 7 *f* f * •* o o' « « <*- v , ^ E5pd^<^0 o A ’A - > A ^ * c °t *'* . o’° A ^ » aAoV ,CT ss*«. <V * S' x 0 ’ >#’ ❖ cv V *A < 0' > M \% *" V</> ,\V.0.V' QQ* av <$» ° WWW+ -v* ^ *• . ^,**., , . » _A A^K * V A *> '■ A >5'■' , V, ■4 «V ^ y. N rj* » <b 2> -A A V * ^ .»».ca * *'' a . >1 •« \ ,,'i*0^t»"‘, ^ ■ <..' • ^ ^ r\ (~, ■ A * j |i4 r- ^ A ♦ « ^ A « * AV ,J^. « * S A ''•If y 0 * X * AX /y y ss A 'xD * 0 « X /V^> cP- •bo' r«^l0L'. ^ > 'SmiSp* >rooi * \° ^ 5 ° ^ ^ ^ * .0 n 0 ^ A" y it o ^ ^ . # # I ' C »^A'0 s- *- *- k~* * bi MN 0 0<’ " *^'Vs ^ ' vS - ^O. \> A* (A ^ <» .c, O aV <%> a WMW* ^ ^ <X ^ A 4 oV ^ - - < » ^ •/0«x'i> A S' ' b a\V , V I ^ A1^,* 1 °o G0> ° J ‘ % % '* wv * / ."“ '-1 - ^ ^ v0 o^ /? i *w3l \ ^ n\v \00^ * V 0J ii‘ A v»aT>*\a \>rr~'V «v0> s-> s,^? ' 'f O \; « < 0 A > * 1 Ss * * / ^ A /jsfe\ % ^ a- *' * i ° v\^' ^ a ' v> "%■ » o \V ./> ^ A O' y„ . -fc Av ^ z ^ * «rvV ^ ^ ^ , 0 * V xir* * v * * * S A v| (V^ C° 0 « A* , *V A ” ■**-, ^ '^C/J/-ar 'f r\ fv y '^vS-’ <.