Structure, Function, and Control of the Musculoskeletal Network Arxiv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Larynx Anatomy

LARYNX ANATOMY Elena Rizzo Riera R1 ORL HUSE INTRODUCTION v Odd and median organ v Infrahyoid region v Phonation, swallowing and breathing v Triangular pyramid v Postero- superior base àpharynx and hyoid bone v Bottom point àupper orifice of the trachea INTRODUCTION C4-C6 Tongue – trachea In women it is somewhat higher than in men. Male Female Length 44mm 36mm Transverse diameter 43mm 41mm Anteroposterior diameter 36mm 26mm SKELETAL STRUCTURE Framework: 11 cartilages linked by joints and fibroelastic structures 3 odd-and median cartilages: the thyroid, cricoid and epiglottis cartilages. 4 pair cartilages: corniculate cartilages of Santorini, the cuneiform cartilages of Wrisberg, the posterior sesamoid cartilages and arytenoid cartilages. Intrinsic and extrinsic muscles THYROID CARTILAGE Shield shaped cartilage Right and left vertical laminaà laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple) M:90º F: 120º Children: intrathyroid cartilage THYROID CARTILAGE Outer surface à oblique line Inner surface Superior border à superior thyroid notch Inferior border à inferior thyroid notch Superior horns à lateral thyrohyoid ligaments Inferior horns à cricothyroid articulation THYROID CARTILAGE The oblique line gives attachement to the following muscles: ¡ Thyrohyoid muscle ¡ Sternothyroid muscle ¡ Inferior constrictor muscle Ligaments attached to the thyroid cartilage ¡ Thyroepiglottic lig ¡ Vestibular lig ¡ Vocal lig CRICOID CARTILAGE Complete signet ring Anterior arch and posterior lamina Ridge and depressions Cricothyroid articulation -

The Muscular System Views

1 PRE-LAB EXERCISES Before coming to lab, get familiar with a few muscle groups we’ll be exploring during lab. Using Visible Body’s Human Anatomy Atlas, go to the Views section. Under Systems, scroll down to the Muscular System views. Select the view Expression and find the following muscles. When you select a muscle, note the book icon in the content box. Selecting this icon allows you to read the muscle’s definition. 1. Occipitofrontalis (epicranius) 2. Orbicularis oculi 3. Orbicularis oris 4. Nasalis 5. Zygomaticus major Return to Muscular System views, select the view Head Rotation and find the following muscles. 1. Sternocleidomastoid 2. Scalene group (anterior, middle, posterior) 2 IN-LAB EXERCISES Use the following modules to guide your exploration of the head and neck region of the muscular system. As you explore the modules, locate the muscles on any charts, models, or specimen available. Please note that these muscles act on the head and neck – those that are located in the neck but act on the back are in a separate section. When reviewing the action of a muscle, it will be helpful to think about where the muscle is located and where the insertion is. Muscle physiology requires that a muscle will “pull” instead of “push” during contraction, and the insertion is the part that will move. Imagine that the muscle is “pulling” on the bone or tissue it is attached to at the insertion. Access 3D views and animated muscle actions in Visible Body’s Human Anatomy Atlas, which will be especially helpful to visualize muscle actions. -

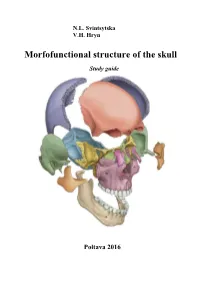

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

Head & Neck Muscle Table

Robert Frysztak, PhD. Structure of the Human Body Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine HEAD‐NECK MUSCLE TABLE PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT DISTAL ATTACHMENT MUSCLE INNERVATION MAIN ACTIONS BLOOD SUPPLY MUSCLE GROUP (ORIGIN) (INSERTION) Anterior floor of orbit lateral to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), inferior Abducts, elevates, and laterally Inferior oblique Lateral sclera deep to lateral rectus Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular nasolacrimal canal division rotates eyeball Inferior aspect of eyeball, posterior to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), inferior Depresses, adducts, and laterally Inferior rectus Common tendinous ring Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular corneoscleral junction division rotates eyeball Lateral aspect of eyeball, posterior to Lateral rectus Common tendinous ring Abducent nerve (CN VI) Abducts eyeball Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular corneoscleral junction Medial aspect of eyeball, posterior to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), inferior Medial rectus Common tendinous ring Adducts eyeball Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular corneoscleral junction division Passes through trochlea, attaches to Body of sphenoid (above optic foramen), Abducts, depresses, and medially Superior oblique superior sclera between superior and Trochlear nerve (CN IV) Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular medial to origin of superior rectus rotates eyeball lateral recti Superior aspect of eyeball, posterior to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), superior Elevates, adducts, and medially Superior rectus Common tendinous ring Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular the corneoscleral junction division -

A Note Ontwo Abnormal Laryngeal

A NOTE ON TWO ABNORMAL LARYNGEAL MUSCLES IN A ZULU BY LAWRENCE H. WELLS AND EDRIC A. THOMAS Department of Anatomy, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg CHARLES, a Zulu labourer, aged 69, died of pulmonary tuberculosis on September 2nd, 1925. His body was dissected in the Department of Anatomy of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. In the course of the dissection there were observed, in addition to various pathological conditions, numerous structural abnormalities not referable to pathological causes. Of the pathological conditions, the principal were ad- vanced pulmonary tuberculosis accompanied byenlargementof the rightatrium of the heart, duodenal ulcer, and degenerative changes in the small intestine, accompanied by widespread haemorrhages into the submucous coat, which were regarded by Dr A. Sutherland Strachan, Senior Lecturer in Pathology, as due to anthrax. There were also present an enlarged liver, complete fibrosis of the left vertebral artery, and appearances in the kidney suggesting paren- chymatous nephritis. Among the abnormalities observed were the following: The hemiazygos vein emerged from the substance of the kidney near the upper pole, and formed with the accessory hemiazygos and left superior intercostal veins a continuous venous trunk opening into the left innominate vein. On the left side the subscapular and posterior circumflex humeral arteries had a common origin from the third part of the axillary artery. On the right side the subscapular artery arose from the second part of the axillary artery instead of from the third part. On the right side also the radial artery divided into its two terminal branches some distance proximal to the wrist joint. -

Trapezius Origin: Occipital Bone, Ligamentum Nuchae & Spinous Processes of Thoracic Vertebrae Insertion: Clavicle and Scapul

Origin: occipital bone, ligamentum nuchae & spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae Insertion: clavicle and scapula (acromion Trapezius and scapular spine) Action: elevate, retract, depress, or rotate scapula upward and/or elevate clavicle; extend neck Origin: spinous process of vertebrae C7-T1 Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula Minor Action: adducts & performs downward rotation of scapula Origin: spinous process of superior thoracic vertebrae Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula from Major spine to inferior angle Action: adducts and downward rotation of scapula Origin: transverse precesses of C1-C4 vertebrae Levator Scapulae Insertion: vertebral border of scapula near superior angle Action: elevates scapula Origin: anterior and superior margins of ribs 1-8 or 1-9 Insertion: anterior surface of vertebral Serratus Anterior border of scapula Action: protracts shoulder: rotates scapula so glenoid cavity moves upward rotation Origin: anterior surfaces and superior margins of ribs 3-5 Insertion: coracoid process of scapula Pectoralis Minor Action: depresses & protracts shoulder, rotates scapula (glenoid cavity rotates downward), elevates ribs Origin: supraspinous fossa of scapula Supraspinatus Insertion: greater tuberacle of humerus Action: abduction at the shoulder Origin: infraspinous fossa of scapula Infraspinatus Insertion: greater tubercle of humerus Action: lateral rotation at shoulder Origin: clavicle and scapula (acromion and adjacent scapular spine) Insertion: deltoid tuberosity of humerus Deltoid Action: -

MIDFACE FRACTURES – an OVERVIEW Correspondance To: Dr

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 7, Issue 4, 2020 MIDFACE FRACTURES – AN OVERVIEW Correspondance to: Dr. Visalakshi kaleeswaran1, Post graduate in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. Author Details: Dr. Visalakshi kaleeswaran1, Dr. Balakrishnan Ramalingam2, Post graduate in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. professor in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. 1. INTRODUCTION Fractures of the midface pose a significant medical problem as for his or her complexity, frequency and their socio-economic impact. Inter disciplinary approaches and up-to-date diagnostic and surgical techniques provide favorable results in the majority of cases though. Traffic accidents are the leading cause and male adults in their thirties are affected most often. Treatment algorithms for nasal fractures, maxillary and zygoma fractures are widely prescribed whereas trauma to the sinus and therefore the orbital apex are matter of current debate. As for the fractures of the sinus a robust tendency towards minimized approaches are often seen. Obliteration and cranialization seem to decrease in numbers. Some critical remarks in terms of high dose methyl prednisolone therapy for traumatic optic nerve injury seem to be appropriate. Intraoperative cone beam radiographs and pre shaped titanium mesh implants for orbital reconstruction are new techniques and essential aspects in midface traumatology. Fractures of the anterior skull base with cerebrospinal fluid leaks show very promising results in endonasal endoscopic repair. The main focus is placed on bony injuries. -

Coracoid Process Anatomy: a Cadaveric Study of Surgically Relevant Structures Jorge Chahla, M.D., Ph.D., Daniel Cole Marchetti, B.A., Gilbert Moatshe, M.D., Márcio B

Quantitative Assessment of the Coracoacromial and the Coracoclavicular Ligaments With 3-Dimensional Mapping of the Coracoid Process Anatomy: A Cadaveric Study of Surgically Relevant Structures Jorge Chahla, M.D., Ph.D., Daniel Cole Marchetti, B.A., Gilbert Moatshe, M.D., Márcio B. Ferrari, M.D., George Sanchez, B.S., Alex W. Brady, M.Sc., Jonas Pogorzelski, M.D., M.H.B.A., George F. Lebus, M.D., Peter J. Millett, M.D., M.Sc., Robert F. LaPrade, M.D., Ph.D., and CAPT Matthew T. Provencher, M.D., M.C., U.S.N.R. Purpose: To perform a quantitative anatomic evaluation of the (1) coracoid process, specifically the attachment sites of the conjoint tendon, the pectoralis minor, the coracoacromial ligament (CAL), and the coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments in relation to pertinent osseous and soft tissue landmarks; (2) CC ligaments’ attachments on the clavicle; and (3) CAL attachment on the acromion in relation to surgically relevant anatomic landmarks to assist in planning of the Latarjet procedure, acromioclavicular (AC) joint reconstructions, and CAL resection distances avoiding iatrogenic injury to sur- rounding structures. Methods: Ten nonpaired fresh-frozen human cadaveric shoulders (mean age 52 years, range 33- 64 years) were included in this study. A 3-dimensional coordinate measuring device was used to quantify the location of pertinent bony landmarks and soft tissue attachment areas. The ligament and tendon attachment perimeters and center points on the coracoid, clavicle, and acromion were identified and subsequently dissected off the bone. Coordinates of points along the perimeters of attachment sites were used to calculate areas, whereas coordinates of center points were used to determine distances between surgically relevant attachment sites and pertinent bony landmarks. -

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and Main Principals Of

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and main principals of anatomical, pharmaceutical and clinical terminology (Student's book) Simferopol, 2017 Contents No. Topics Page 1. UNIT I. Latin language history. Phonetics. Alphabet. Vowels and consonants classification. Diphthongs. Digraphs. Letter combinations. 4-13 Syllable shortness and longitude. Stress rules. 2. UNIT II. Grammatical noun categories, declension characteristics, noun 14-25 dictionary forms, determination of the noun stems, nominative and genitive cases and their significance in terms formation. I-st noun declension. 3. UNIT III. Adjectives and its grammatical categories. Classes of adjectives. Adjective entries in dictionaries. Adjectives of the I-st group. Gender 26-36 endings, stem-determining. 4. UNIT IV. Adjectives of the 2-nd group. Morphological characteristics of two- and multi-word anatomical terms. Syntax of two- and multi-word 37-49 anatomical terms. Nouns of the 2nd declension 5. UNIT V. General characteristic of the nouns of the 3rd declension. Parisyllabic and imparisyllabic nouns. Types of stems of the nouns of the 50-58 3rd declension and their peculiarities. 3rd declension nouns in combination with agreed and non-agreed attributes 6. UNIT VI. Peculiarities of 3rd declension nouns of masculine, feminine and neuter genders. Muscle names referring to their functions. Exceptions to the 59-71 gender rule of 3rd declension nouns for all three genders 7. UNIT VII. 1st, 2nd and 3rd declension nouns in combination with II class adjectives. Present Participle and its declension. Anatomical terms 72-81 consisting of nouns and participles 8. UNIT VIII. Nouns of the 4th and 5th declensions and their combination with 82-89 adjectives 9. -

The Age Order of Epiphyseal Union Around Elbow Joint - a Radiological Study in Vidarbha

International Journal of Recent Trends in Science And Technology, ISSN 2277-2812 E-ISSN 2249-8109, Volume 10, Issue 2, 2014 pp 251-255 The Age Order of Epiphyseal Union around Elbow Joint - A Radiological Study in Vidarbha Nemade K. S.1*, Kamdi N. Y.2, Meshram M. M.3 1Assistant Professor, 2Associate Professor, 3Professor, Department of Anatomy, GMC, Nagpur, Maharashtra, INDIA. *Corresponding Address: [email protected] Research Article Abstract: Age of union of epiphysis is an important objective even by the workers from the various provinces of the method of age determination which is a difficult task for medico- Indian subcontinent ( Lal and Nat 1934 11 ; Pillai 1936 15 ; legal person. However, this age varies with racial, geographic, Galstaun 1937 9; Basu and Basu 1938 3,4 ; Lal and climatic and various other factors. Study of various text books in 12 et al 8 Anatomy and Radiology exhibits a glaring discrepancy as regards Townsend 1939 ; Gupta . 1974 ). Because of the the ages at which the different epiphyses fuse with the respective existence of such racial, geographic and climatic diaphyses in long bones. These variations have suggested need of variations, need for separate standards of ossification for separate standard of ossification for separate regions. This leads us separate regions have been suggested (Loder et al 1993 14 ; to study ages of epiphyseal union around elbow joint, a rarely Koc et al. 2001 10 ; Crowder et al. 2005 6). So, the present studied joint. Study was performed in total 320 healthy subjects work is undertaken as a pilot study to investigate the ages having ages from 13 to 23 years and length of residence in Vidarbh more than 10 years. -

Sesamoid Bone in the Tendon of the Supinator Muscle of Dogs: Incidence and Comparison of Radiographic and Computed Tomographic Features

Sesamoid bone in the tendon of the supinator muscle of dogs: incidence and comparison of radiographic and computed tomographic features Word count: 8473 Manon Dorny Student number: 01609678 Supervisor: Dr. Ingrid Gielen Supervisor: Prof. dr. Wim Van Den Broeck Supervisor: Dr. Aquilino Villamonte Chevalier A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Veterinary Medicine Academic year: 2018 - 2019 Ghent University, its employees and/or students, give no warranty that the information provided in this thesis is accurate or exhaustive, nor that the content of this thesis will not constitute or result in any infringement of third-party rights. Ghent University, its employees and/or students do not accept any liability or responsibility for any use which may be made of the content or information given in the thesis, nor for any reliance which may be placed on any advice or information provided in this thesis. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the people that helped me accomplish this thesis and helped me achieve my degree in veterinary science. First of all I would like to thank Dr. Ingrid Gielen, Dr. Aquilino Villamonte Chevalier and Prof. Dr. Wim Van Den Broeck. I thank them all for their time spend in helping me with my research, their useful advice and their endless patience. Without their help, I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish this thesis. Next I would like to thank my family and friends for their continuing support and motivation during the last years of vet school. My parents and partner especially, for all the mental breakdowns they had to endure in periods of exams and deadlines. -

Morphology and Evolution of Sesamoid Elements in Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera)

Morphology and Evolution of Sesamoid Elements in Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) Author(s): http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7292-3256Lucila Inés Amador, Norberto Pedro Giannini, http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8807-7499Nancy B. Simmons and http:// orcid.org/0000-0002-4615-5011Virginia Abdala Source: American Museum Novitates, (3905):1-40. Published By: American Museum of Natural History https://doi.org/10.1206/3905.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1206/3905.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Number 3905, 38 pp. August 17, 2018 Morphology and Evolution of Sesamoid Elements in Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) LUCILA INÉS AMADOR,1 NORBERTO PEDRO GIANNINI,1, 2, 3 NANCY B. SIMMONS,2 AND VIRGINIA ABDALA4 ABSTRACT Sesamoids are skeletal elements found within a tendon or ligament as it passes around a joint or bony prominence.