Persistence of Transported Lichen at a Hummingbird Nest Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes Fulgens Donald R

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Department of Biology and Chemistry Chemistry 6-27-2018 Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes fulgens Donald R. Powers George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/bio_fac Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, and the Poultry or Avian Science Commons Recommended Citation Powers, Donald R., "Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes fulgens" (2018). Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Chemistry. 123. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/bio_fac/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Chemistry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rivoli's Hummingbird Eugenes fulgens Order: CAPRIMULGIFORMES Family: TROCHILIDAE Version: 2.1 — Published June 27, 2018 Donald R. Powers Introduction Rivoli's Hummingbird was named in honor of the Duke of Rivoli when the species was described by René Lesson in 1829 (1). Even when it became known that William Swainson had written an earlier description of this species in 1827, the common name Rivoli's Hummingbird remained until the early 1980s, when it was changed to Magnificent Hummingbird. In 2017, however, the name was restored to Rivoli's Hummingbird when the American Ornithological Society officially recognized Eugenes fulgens as a distinct species from E. spectabilis, the Talamanca Hummingbird, of the highlands of Costa Rica and western Panama (2). See Systematics: Related Species. -

Aullwood's Birds (PDF)

Aullwood's Bird List This list was collected over many years and includes birds that have been seen at or very near Aullwood. The list includes some which are seen only every other year or so, along with others that are seen year around. Ciconiiformes Great blue heron Green heron Black-crowned night heron Anseriformes Canada goose Mallard Blue-winged teal Wood duck Falconiformes Turkey vulture Osprey Sharp-shinned hawk Cooper's hawk Red-tailed hawk Red-shouldered hawk Broad-winged hawk Rough-legged hawk Marsh hawk American kestrel Galliformes Bobwhite Ring-necked pheasant Gruiformes Sandhill crane American coot Charadriformes Killdeer American woodcock Common snipe Spotted sandpiper Solitary sandpiper Ring-billed gull Columbiformes Rock dove Mourning dove Cuculiformes Yellow-billed cuckoo Strigiformes Screech owl Great horned owl Barred owl Saw-whet owl Caprimulgiformes Common nighthawk Apodiformes Chimney swift Ruby-throated hummingbird Coraciformes Belted kinghisher Piciformes Common flicker Pileated woodpecker Red-bellied woodpecker Red-headed woodpecker Yellow-bellied sapsucker Hairy woodpecker Downy woodpecker Passeriformes Eastern kingbird Great crested flycatcher Eastern phoebe Yellow-bellied flycatcher Acadian flycatcher Willow flycatcher Least flycatcher Eastern wood pewee Olive-sided flycatcher Tree swallow Bank swallow Rough-winged swallow Barn swallow Purple martin Blue jay Common crow Black-capped chickadee Carolina chickadee Tufted titmouse White-breasted nuthatch Red-breasted nuthatch Brown creeper House wren Winter wren -

Energy Metabolism and Body Temperature in the Blue-Naped Mousebird (Urocolius Macrourus) During Torpor

Ornis Fennica 76:211-219 . 1999 Energy metabolism and body temperature in the Blue-naped Mousebird (Urocolius macrourus) during torpor Ralph Schaub, Roland Prinzinger and Elke Schleucher Schaub, R., Prinzinger, R. &Schleucher, E., AK Stoffwechselphysiologie, Zoologisches Institut, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universitdt, Siesmayerstra²e 70, 60323 Frankfurt/ Main, Germany Received 13 March 1998, accepted IS September 1999 Mousebirds (Coliiformes) respond to cold exposure and food limitation with nightly bouts of torpor. During torpor, metabolic rate and body temperature decrease mark- edly, which results in energy savings. The decrease in body temperature is a regulated phenomenon as is also the arousal which occurs spontaneously without external stimuli. During arousal, Blue-naped Mousebirds warm at a rate of 1 °C/min . This process requires significant amounts of energy . Our calculations show that the overall savings for the whole day are 30% at an ambient temperature of 15°C when daylength is 10 hours . Using glucose assays and RQ measurements, we found that during fasting, the birds switch to non-carbohydrate metabolism at an early phase of the day . This may be one of triggers eliciting torpor. By using cluster analysis of glucose levels we could clearly divide the night phase into a period of effective energy saving (high glucose levels) and arousal (low glucose levels) . 1 . Introduction 1972) . This kind of nutrition is low in energy, so the birds may face periods of energy deficiency The aim of this study is to get information about (Schifter 1972). To survive these times of starva- the daily energy demand and the thermal regula- tion, they have developed a special physiological tion in small birds. -

Bird Checklist

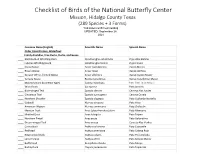

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Conjugate and Disjunctive Saccades in Contrasting Oculomotor

0270-6474/0506-i 418$02.00/O The Journal of Neuroscmce Copyright 0 Society for Neuroscience Vol. 5. No. 6 pp. 1418-1428 Printed m U.S.A. June 1985 Conjugate and Disjunctive Saccades in Two Avian Species with Contrasting Oculomotor Strategies’ JOSH WALLMAN* AND JOHN D. PETTIGREWS3 *Department of Biology, City College of City University of New York, New York, New York 10031, and *National Vision Research institute of Australia, 386 Cardigan Street, Car/ton 3052, Australia Abstract intervals. We hypothesize that saccades have such an endogenous pattern in time and space, and that this pattern represents an We have recorded with the magnetic search coil method oculomotor strategy for a species. the spontaneous saccades of two species of predatory birds, As a start in investigating this hypothesis, we have taken advan- which differ in the relative importance of panoramic and tage of the diversity of avian visual adaptations by studying spon- fovea1 vision. The little eagle (Haliaetus morphnoides) hunts taneous saccades made by two species, the tawny frogmouth and from great heights and has no predators, whereas the tawny the little eagle, which we presume have different oculomotor require- frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) hunts from perches near the ments, particularly with respect to binocular coordination. The sac- ground, is preyed upon, and frequently adopts an immobile cades of both eyes were studied as the animals freely viewed the camouflage posture. laboratory with their heads restrained. Although this situation is of We find that both birds spend most of the time with their course far from what the animals would experience in their natural eyes confined to a small region of gaze, the primary position circumstances, it provides an opportunity to compare the two of gaze; in this position, the visual axes are much more species under identical conditions without the complication of differ- diverged in the frogmouth than in the eagle, thereby giving it ences in head movements. -

The Origin and Diversification of Birds

Current Biology Review The Origin and Diversification of Birds Stephen L. Brusatte1,*, Jingmai K. O’Connor2,*, and Erich D. Jarvis3,4,* 1School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Grant Institute, King’s Buildings, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh EH9 3FE, UK 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3Department of Neurobiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA 4Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD 20815, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] (S.L.B.), [email protected] (J.K.O.), [email protected] (E.D.J.) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.003 Birds are one of the most recognizable and diverse groups of modern vertebrates. Over the past two de- cades, a wealth of new fossil discoveries and phylogenetic and macroevolutionary studies has transformed our understanding of how birds originated and became so successful. Birds evolved from theropod dino- saurs during the Jurassic (around 165–150 million years ago) and their classic small, lightweight, feathered, and winged body plan was pieced together gradually over tens of millions of years of evolution rather than in one burst of innovation. Early birds diversified throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous, becoming capable fliers with supercharged growth rates, but were decimated at the end-Cretaceous extinction alongside their close dinosaurian relatives. After the mass extinction, modern birds (members of the avian crown group) explosively diversified, culminating in more than 10,000 species distributed worldwide today. Introduction dinosaurs Dromaeosaurus albertensis or Troodon formosus.This Birds are one of the most conspicuous groups of animals in the clade includes all living birds and extinct taxa, such as Archaeop- modern world. -

MD-Birds-2021-Envirothon-3Pp

3/23/2021 Maryland Envirothon: Class Aves KERRY WIXTED WILDLIFE AND HERITAGE SERVICE March 2021 1 Aves Overview •> 450 species in Maryland •Extirpated species include: ◦Bewick’s Wren ◦Greater Prairie Chicken ◦Red-cockaded Woodpecker American Woodcock (Scolopax minor) chick by Kerry Wixted Note: This guide is an overview of select species found in Maryland. The taxonomy and descriptions are based off Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America, 6th Ed. 2 Order: Anseriformes • Web-footed waterfowl • Family Anatidae • Ducks, geese & swans Male Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) Order: Anseriformes; Family Anatidae 3 1 3/23/2021 Cygnus- Swans Mute Swan Tundra Swan Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus olor) (Cygnus columbianus) (Cygnus buccinator) Invasive. Adult black-knobbed orange Winter resident. Adult bill black, usually Winter resident. Adult all black bill bill tilts down; immature is dingy with with small yellow basal spot; immature with straight ridge; more nasal calls is dingy in color with pinkish bill; makes than tundra swan pinkish bill; makes hissing sounds mellow-high pitched woo-ho, woo-woo noise Order: Anseriformes; Family Anatidae By Matthew Beziat CC by NC 2.0 By Jen Goellnitz CC by NC 2.0 4 Dabbling Ducks- feed by dabbling & upending Male Female , Maryland Biodiversity Project Biodiversity ,Maryland Hubick By Bill Bill By By Kerry Wixted Kerry By American Black Duck (Anas rubripes) Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) Year-round resident. Dusky black duck with white wing linings Year-round resident. Adult males have green head w/ evident in flight; resembles a female mallard but has black white neck ring & females are mottled in color ; borders on secondary wing feathers; can hybridize with resembles an American Black Duck mallard but has mallards white borders on secondary wing feathers Order: Anseriformes; Family Anatidae 5 Diving Ducks- feed by diving; legs close to tail CC by NC NC 2.0CC by Beziat By Judy Gallagher CC by by 2.0CC Gallagher Judy By By Matthew Matthew By Canvasback (Aythya valisneria) Redhead (Aythya americana) Winter resident. -

Developmental Origins of Mosaic Evolution in the Avian Cranium

Developmental origins of mosaic evolution in the SEE COMMENTARY avian cranium Ryan N. Felicea,b,1 and Anjali Goswamia,b,c aDepartment of Genetics, Evolution, and Environment, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5DB, United Kingdom; and cDepartment of Earth Sciences, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom Edited by Neil H. Shubin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved December 1, 2017 (received for review September 18, 2017) Mosaic evolution, which results from multiple influences shaping genes. For example, manipulating the expression of Fgf8 generates morphological traits and can lead to the presence of a mixture of correlated responses in the growth of the premaxilla and palatine ancestral and derived characteristics, has been frequently invoked in in archosaurs (11). Similarly, variation in avian beak shape and describing evolutionary patterns in birds. Mosaicism implies the size is regulated by two separate developmental modules (7). hierarchical organization of organismal traits into semiautonomous Despite the evidence for developmental modularity in the avian subsets, or modules, which reflect differential genetic and develop- skull, some studies have concluded that the cranium is highly in- mental origins. Here, we analyze mosaic evolution in the avian skull tegrated (i.e., not subdivided into semiautonomous modules) (9, using high-dimensional 3D surface morphometric data across a 10, 12). In light of recent evidence that diversity in beak mor- broad phylogenetic sample encompassing nearly all extant families. phology may not be shaped by dietary factors (12), it is especially We find that the avian cranium is highly modular, consisting of seven critical to investigate other factors that shape the evolution of independently evolving anatomical regions. -

A New Short-Legged Landbird from the Early Eocene of Wyoming and Contemporaneous European Sites

A new short-legged landbird from the early Eocene of Wyoming and contemporaneous European sites GERALD MAYR and MICHAEL DANIELS Mayr, G. & Daniels, M. 2001. A new short-legged landbird from the early Eocene of Wy- oming and contemporaneous European sites. -Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 46, 3, 393-402. Fluvioviridavisplatyrhamphus, a new genus and species of short-legged landbirds from the Lower Eocene Green fiver Formation (Wyoming, USA) is described. The taxon is known from a single, nearly complete and slightly dissociated skeleton which was made the paratype of the putative oilbird Prefica nivea Olson, 1987 (Steatornithidae, Capri- mulgiformes). Apart from the greatly abbreviated tarsometatarsus,Fluvioviridavis espe- cially corresponds to recent oilbirds in the unusually wide proximal end of the humerus. However, in other features, e.g., the shape of its much longer beak, the Eocene taxon is clearly distinguished from the recent oilbird (Steatornis). In contrast, Prefica nivea agrees with Steatornis in the shape of the mandible but differs in the much narrower proximal end of the humerus. At present, no derived character convincingly supports a classification of E platyrhamphus into any of the higher avian taxa. The species is here classified 'order and family incertae sedis'. An isolated skull from the Middle Eocene of Messel (Hessen, Germany) is tentatively assigned to ?Fluvioviridavissp., and associated bones from the Lower Eocene London Clay of Walton-on-the-Naze (Essex, England) might also be related to the genus Fluvioviridavis. Key words : Fossil birds, Eocene, Fluvioviridavis, Green fiver Formation, Messel, London Clay. Gerald Mayr [[email protected]&rt.de], Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Division of Ornithology, Senckenberganlage 25,D-60325 Franert a.M., Germany; Michael Daniels [nazeman @ beeb.net], 118 Dulwich Road, Holland-on-Sea, Clacton- on-Sea, C015 5LU Essex, England. -

Owls: Formidable Predators of the Kenai Peninsula by Toby Burke

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 9, No. 6 • February 16, 2007 Owls: Formidable predators of the Kenai Peninsula by Toby Burke Late winter is the time of the year when residents accounting for an incredible one to five percent of their of the Kenai Peninsula often become aware of our res- total body mass, depending on the species. Their pro- ident owls. Why? Because their annual breeding cy- portionately large eyes improve their sight especially cle begins a new when owls start vocalizing to at- under low light conditions by enabling them to collect tract mates and establish and defend breeding terri- more light. The eye itself contains an abundance of tories. There are eight species of owls that frequent “rod” cells that aid them in processing the light. These the Kenai Peninsula either as winter visitants, sum- cells are very sensitive to light and movement. Cells mer breeders, or year-round residents. They are Great that are very sensitive to color are known as “cone” Gray Owl, Great Horned Owl, Snowy Owl, Short- cells. Owls possess few cone cells and these cells are eared Owl, Northern Hawk Owl, Boreal Owl, North- not very sensitive in low light conditions so most owls ern Saw-whet Owl, and Western Screech-owl. While see in limited color or in monochrome. most species of owls can be characterized as nocturnal Furthermore, the exceptional light gathering abil- and a few as diurnal almost all of our owl species are ity is enhanced by the reflective layer behind the eye crepuscular to some degree, exhibiting increased ac- called the tapetum lucidum. -

Bird Nests – Non-Passeriformes, Part 2

Glime, J. M. 2017. Bird Nests – Non-Passeriformes, part 2. Chapt. 16-5. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 2. Bryological 16-5-1 Interaction. eBook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 19 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology2/>. CHAPTER 16-5 BIRD NESTS – NON-PASSERIFORMES, PART 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Columbiformes: Pigeons & Doves ................................................................................................................. 16-5-2 Columbidae – Pigeons & Doves ............................................................................................................... 16-5-2 Cuculiformes: Cuckoos, etc. ........................................................................................................................... 16-5-2 Cuculidae – Typical Cuckoos ................................................................................................................... 16-5-2 Strigiformes: Owls .......................................................................................................................................... 16-5-3 Strigidae – Typical Owls ........................................................................................................................... 16-5-3 Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus) .......................................................................................................... 16-5-3 Burrowing Owls (Athene cunicularia) ..............................................................................................