Mental Health in This Country. He Also Discussed Therapeutic Case Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

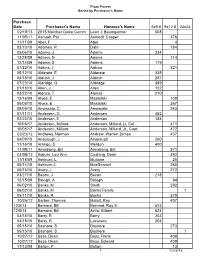

Armed Forces Plaza Paver

Plaza Pavers Sorted by Purchaser's Name Purchase Date Purchaser's Name Honoree's Name 6x9 # 9x12 # 24x24 02/18/13 2013 Member Guest Comm Leon J. Baumgartner 508 11/05/11 Aamodt, Pat Aamodt, Casper 376 11/11/09 Abel, F Abel 4 03/10/10 Adamek, R Dalin 184 05/06/10 Adams, J Adams 334 12/28/09 Adams, N Adams 114 12/14/09 Adams, S Adams 119 07/22/10 Adkins, J Adkins 321 05/12/10 Alderete, E Alderete 335 04/18/10 Aldrich, J Aldrich 297 07/23/10 Aldridge, G Aldridge 399 01/18/10 Allen, J Allen 152 03/22/10 Alonzo, T Alonzo 210 12/16/09 Alyea, E Mastalski 100 05/06/10 Alyea, E Mastalski 267 05/06/10 Amoscato, C Amoscato 263 07/11/11 Andersen, G Andersen 452 02/23/10 Anderson, E Anderson 184 10/05/17 Anderson, Millard Anderson, Millard, Lt. Col. 471 10/05/17 Anderson, Millard Anderson, Millard, Jr., Capt. 472 03/23/13 Andrews, Norman Andrew, Warren James 437 04/09/10 Anspaugh, J Anspaugh 260 11/16/10 Arango, S Weldon 400 11/08/11 Armstrong, Bill Armstrong, Bill 371 03/05/12 Asburn, Lou Ann Cushing, Dean 392 11/18/09 Ashburn, L Mullane 25 05/14/10 Ashburn, L MacDonnell 265 05/15/10 Avery, J Avery 272 03/27/10 Bacon, J Bacon 218 12/15/09 Balogh, A Balogh 94 06/02/10 Banks, M Smith 292 06/02/10 Banks, M Banks Family 1 05/11/10 Banks, R Banks 270 10/26/12 Barber, Thomas Malott, Ray 407 12/0/13 Barnard, Bill Barnard, Roy S. -

FERC PDF (Unofficial) 5/11/2016 5:09:03 PM

20160512-5033 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 5/11/2016 5:09:03 PM May 11, 2016 Ms. Kimberly D. Bose Secretary Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Office of the Secretary 888 First Street, NE Washington, D.C. 20426 Dear Secretary Bose, We, the undersigned organizations from New Jersey and Pennsylvania, are delivering to FERC today the petition signatures of over 8,000 people who are joining us to express our opposition to the PennEast Pipeline (CP15-558), an unneeded and damaging project. The petition signed by these individuals reads as follows: We call on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to reject the proposed PennEast Pipeline. This pipeline is environmentally destructive, unnecessary and unwanted. The pipeline would cut through preserved open spaces and sensitive waterways, result in an enormous surplus of gas that we don’t need, and is opposed by landowners and municipalities along its route. We urge you to reject this proposal. Representatives from our organizations have come to FERC in person today, joined by seven local mayors opposed to the pipeline, to stress the importance of hearing the voices of the many organizations, local officials and thousands of citizens opposed to the project. The vast majority of the more than 1,400 intervenors and landowners in the path of the pipeline oppose it. Many municipalities in Pennsylvania and every New Jersey municipality along the route has officially opposed the project. The PennEast Pipeline would cut through one of the most environmentally sensitive regions in the Delaware River watershed, damaging thousands of acres of preserved open space and some of the cleanest streams in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. -

Nassau County Website Nct Public Notice of County

NASSAU COUNTY WEBSITE NCT PUBLIC NOTICE OF COUNTY TREASURER'S SALE OF TAX LIENS ON REAL ESTATE Notice is hereby given that I shall, commencing on February 18, 2020, sell at public on-line auction the tax liens on real estate herein-after described, unless the owner, mortgagee, occupant of or any other party-in- interest in such real estate shall pay to the County Treasurer by February 13, 2020 the total amount of such unpaid taxes or assessments with the interest, penalties and other expenses and charges, against the property. Such tax liens will be sold at the lowest rate of interest, not exceeding 10 per cent per six month's period, for which any person or persons shall offer to take the total amount of such unpaid taxes as defined in section 5-37.0 of the Nassau County Administrative Code. Effective with the February 18, 2020 lien sale, Ordinance No. 175-2015 requires a $175.00 per day registration fee for each person who intends to bid at the tax lien sale. Ordinance No. 175-2015 also requires that upon the issuance of the Lien Certificate there is due from the lien buyer a Tax Certificate Issue Fee of $20.00 per lien purchased. Pursuant to the provisions of the Nassau County Administrative Code at the discretion of the Nassau County Treasurer the auction will be conducted online. Further information concerning the procedures for the auction is available at the website of the Nassau County Treasurer at: https://www.nassaucountyny.gov/526/County-Treasurer Should the Treasurer determine that an in-person auction shall be held, same will commence on the 18th day of February, 2020 at the Office of The County Treasurer 1 West Street, Mineola or at some other location to be determined by the Treasurer. -

To Keep Creating!

TO KEEP CREATING! LA LETTRE DE L’ACADÉMIE DES BEAUX-ARTS NUMBER 93 4 | | 1 Editorial • page 3 numéro 93 News : Editorial Emmanuel Guibert, “Comic-Strip Biographies” Exhibition | Palais de l’Institut de France hiver 2020-2021 “Peder Severin Krøyer’s Blue Hour” Exhibition | Musée Marmottan Monet To keep creating! Flore, “L’odeur de la nuit était celle du jasmin” 2018 Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière Photography Prize Of the Académie des Beaux-Arts’ important missions, come out of these Capuan delights with very few new in partnership with the Académie des Beaux-Arts we have always felt that those promoting creation were works to their name. Exhibition | Palais de l’Institut de France a priority. This starts with supporting artists at the For a residency to be useful, it is not enough simply Jan Vičar, “Un cœur dans la rivière” beginning of their careers. Mario Avati – Académie des Beaux-Arts Engraving to provide a workshop and a scholarship. It must be Prize While one might imagine that it has become easier, in integrated into a general plan that enables young artists Exhibition | Palais de l’Institut de France the age of the internet, for creators to make their work to realize a project, to present it and to interact with • pages 4 to 11 known and to promote it, unfortunately that is actually other creators. not so. With this in mind, the Académie des Beaux-Arts is The internet can be a “jungle”; as a famous producer Dossier : To keep creating! currently setting up twenty artists’ workshops spread commented, tongue-in-cheek: “the internet is like a “A project of unparalleled ambition” over several sites in Paris, in Boulogne-Billancourt, and Chinese buffet, there’s a countless selection of dishes An interview with Bénédicte Alliot, by Nadine Eghels in Chars, in the Val-d’Oise. -

Media Info.Indd

UNIVERSITY INFORMATION ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS Location ................................................................................................. Corvallis, Ore. Asst. AD/Communications ..........................................................Steve Fenk Founded ................................................................................................................. 1868 Office Phone ........................................................................... (541) 737-3720 Enrollment..........................................................................................................20,100 Office Fax ................................................................................. (541) 737-3072 Nickname.......................................................................................................... Beavers Assistant/Wrestling Contact ..........................................Melody Stockwell Colors ...............................................................................................Orange and Black Office Phone ........................................................................... (541) 737-3720 President ............................................................................................ Dr. Edward Ray E-mail ...............................................melody.stockwell@oregonstate.edu Director of Athletics .......................................................................Bob De Carolis Website ............................................................................www.osubeavers.com -

Bellagio Forum 10Th Anniv Meeting Summary.Pdf

10th Anniversary Members Meeting April 27-29, 2006 Bellagio, Italy MEETING SUMMARY Perspectives for the Future: Beyond Traditional Partnerships 1 PARTICIPANTS Jens Ambsdorf Lighthouse Foundation www.lighthouse-foundation.org Joao Amorin Fundacao Oriente www.foriente.pt Michèle Boccoz Institut Pasteur www.pasteur.fr Marta Bonifert Regional Environmental Centre for www.rec.org Central and Eastern Europe Charles A. Buchanan, Jr. Luso American Foundation www.flad.pt Cheryl Campbell Television Trust for the Environment www.tve.org Michael E. Conroy Rockefeller Brothers Fund www.rbf.org Will Day UNDP www.undp.org Xavier de Bayser I.DE.A.M www.ideam.fr Carol-Anne De Carolis Institut Veolia Environnement www.institutveoliaenvironnement.org Foster Deibert WestLB AG www.westlb.de Dario Disegni Compagnia di San Paolo www.compagnia.torino.it Jed Emerson Generation Foundation www.generationim.com/foundation Steve Falci Calvert Group www.calvert.com Hans Friederich IUCN www.iucn.org Ralf Frye Bellagio Forum www.bfsd.org Hans-Joachim Gericke Foundation for Music, Art and Nature www.stiftung-mkn.com Somak Ghosh Yesbank Ltd. www.yesbank.in Peter Goldmark Environmental Defense www.environmentaldefense.org Michael Hanssler G. Henkel-Stiftung www.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de Michael Hoelz Deutsche Bank www.umwelt.deutsche-bank.de Michaela Hoelz Heidelberg University www.uni-heidelberg.de Kurt Hoffman Shell Foundation www.shellfoundation.org Leslie Hoffman Earth pledge www.earthpledge.org Dirk Hoffmann Bosch and Siemens Home Appliances www.bsh-group.com Oliver -

Expatriate Entrepreneurship

Expatriate Entrepreneurship Expatriate Entrepreneurship Expatriate Entrepreneurship Entrepreneurship among immigrants is an increasingly important The Role of Accelerators in Network Formation socio-economic phenomenon. To date, immigrant entrepreneurship and Resource Acquisition research has focused on immigrants that decide to engage in self- employment after having established themselves in the host country. Whereas this is arguably the case for the vast majority of immigrant entrepreneurs, it does not cover the field in its totality. This disser- tation is devoted to the study and analysis of those that emigrate Nedim Efendic in order to launch a new venture. I denote this novel group of en- trepreneurs as expatriate entrepreneurs, and I place them into the context of research on entrepreneurship among immigrants. This dissertation also examines how accelerators impact expatriate entre- preneurship. Using a multiple case study at the world’s three first government-funded acceleration programmes that target expatriate entrepreneurs, I show that by their ability to support network forma- tion and resource acquisition, accelerators are major facilitators of expatriate entrepreneurship. Nedim Efendic is a researcher at the Department of Mana- gement and Organization at the Stockholm Nedim Efendic School of Economics. • 201 6 ISBN 978-91-7731-021-1 Doctoral Dissertation in Business Administration Stockholm School of Economics Sweden, 2016 Expatriate Entrepreneurship Expatriate Entrepreneurship Expatriate Entrepreneurship Entrepreneurship among immigrants is an increasingly important The Role of Accelerators in Network Formation socio-economic phenomenon. To date, immigrant entrepreneurship and Resource Acquisition research has focused on immigrants that decide to engage in self- employment after having established themselves in the host country. Whereas this is arguably the case for the vast majority of immigrant entrepreneurs, it does not cover the field in its totality. -

4 Workshop on Emotions and Personality in Personalized

4th Workshop on Emotions and Personality in Personalized Systems (EMPIRE) 2016 Boston, MA, USA, September 16th, 2016 Proceedings edited by Marko Tkalčič Berardina de Carolis Marco de Gemmis Andrej Košir in conjunction with 10th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems (RecSys 2016) ii Preface This volume contains the papers presented at the 4th Workshop on Emotions and Personality in Personalized Systems (EMPIRE), hold as part of the 10th ACM Conference on Recommender System (RecSys), in Boston, MA, USA. RecSys is the premier international forum for the presentation of new research results, systems and techniques in the broad field of recommender systems. Recommendation is a particular form of information filtering, that exploits past behaviors and user similarities to generate a list of information items that is personally tailored to an end-user’s preferences. The EMPIRE workshop focuses on the usage of psychologically-based constructs, such as emotions and personality, in delivering personalized content. The 9 (5 long, 4 short) technical papers included in the proceedings were selected through a rigorous reviewing process, where each paper was reviewed by three PC members. The EMPIRE chairs would like to thank the RecSys workshop chairs, Elizabeth Daly and Dietmar Jannach, for their guidance during the workshop organization. We also wish to thank all authors and all workshops participants for fruitful discussions, the members of the program committee and the external reviewers. All of them secured the workshop’s high quality standards. -

5–6 September 2019

Abstracts of Papers Presented at the 20th European Conference on Knowledge Management ECKM 2019 Hosted By Universidade Europeia de Lisboa Lisbon, Portugal 5–6 September 2019 Copyright The Authors, 2019. All Rights Reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission may be made without written permission from the individual authors. Review Process Papers submitted to this conference have been double-blind peer reviewed before final acceptance to the conference. Initially, abstracts were reviewed for relevance and accessibility and successful authors were invited to submit full papers. Many thanks to the reviewers who helped ensure the quality of all the submissions. Ethics and Publication Malpractice Policy ACPIL adheres to a strict ethics and publication malpractice policy for all publications – details of which can be found here: http://www.academic-conferences.org/policies/ethics-policy-for-publishing-in-the- conference-proceedings-of-academic-conferences-and-publishing-international-limited/ Conference Proceedings The Conference Proceedings is a book published with an ISBN and ISSN. The proceedings have been submitted to a number of accreditation, citation and indexing bodies including Thomson ISI Web of Science and Elsevier Scopus. Author affiliation details in these proceedings have been reproduced as supplied by the authors themselves. The Electronic version of the Conference Proceedings is available to download from DROPBOX http://tinyurl.com/ECKM19 Select Download and then Direct Download to access the Pdf file. Free download is available -

Abstracts of Papers Presented at the 18Th European Conference On

Abstracts of Papers Presented at the 18th European Conference on Knowledge Management ECKM 2017 Hosted By International University of Catalonia Barcelona, Spain 7-8 September 2017 Copyright The Authors, 2017. All Rights Reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission may be made without written permission from the individual authors. Review Process Papers submitted to this conference have been double-blind peer reviewed before final acceptance to the conference. Initially, abstracts were reviewed for relevance and accessibility and successful authors were invited to submit full papers. Many thanks to the reviewers who helped ensure the quality of all the submissions. Ethics and Publication Malpractice Policy ACPIL adheres to a strict ethics and publication malpractice policy for all publications – details of which can be found here: http://www.academic-conferences.org/policies/ethics-policy-for-publishing-in-the- conference-proceedings-of-academic-conferences-and-publishing-international-limited/ Conference Proceedings The Conference Proceedings is a book published with an ISBN and ISSN. The proceedings have been submitted to a number of accreditation, citation and indexing bodies including Thomson ISI Web of Science and Elsevier Scopus. Author affiliation details in these proceedings have been reproduced as supplied by the authors themselves. The Electronic version of the Conference Proceedings is available to download from DROPBOX http://tinyurl.com/eckm2017 Select Download and then Direct Download to access the Pdf file. Free download -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Deleuzean Hybridity in the Films of Leone and Argento Keith Hennessey Brown PhD Film Studies University of Edinburgh 2012 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors, Professor Martine Beugnet, Dr Daniel Yacavone, and the late Professor John Orr. I would then like to thank my parents, Alex and Mary Brown; all my friends, but especially Li-hsin Hsu, John Neilson and Tracey Rosenberg; and my cats, Bebert and Lucia. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................... 5-20 Theory ............................................................................................................. 21-62 -

Specifying and Animating Facial Signals for Discourse in Embodied Conversational Agents

Specifying and Animating Facial Signals for Discourse in Embodied Conversational Agents Doug DeCarlo, Matthew Stone Dpt. of Computer Science and Ctr. for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University fdecarlo,[email protected] http://www.cs.rutgers.edu/˜village/ruth Corey Revilla Entertainment Technology Center, Carnegie Mellon University [email protected] Jennifer J. Venditti Dpt. of Computer Science, Columbia University [email protected] July 3, 2003 Abstract People highlight the intended interpretation of their utterances within a larger discourse by a diverse set of nonverbal signals. These signals represent a key challenge for animated con- versational agents because they are pervasive, variable, and need to be coordinated judiciously in an effective contribution to conversation. In this paper, we describe a freely-available cross- platform real-time facial animation system, RUTH, that animates such high-level signals in syn- chrony with speech and lip movements. RUTH adopts an open, layered architecture in which fine-grained features of the animation can be derived by rule from inferred linguistic structure, allowing us to use RUTH, in conjunction with annotation of observed discourse, to investigate the meaningful high-level elements of conversational facial movement for American English speakers. Keywords: Facial Animation, Embodied Conversational Agents Running head: Animating Facial Conversational Signals This research was supported in part by NSF research instrumentation grant 9818322 and by Rutgers ISATC. Dan DeCarlo drew the original RUTH concept. Radu Gruian and Niki Shah helped with programming; Nathan Folsom-Kovarik and Chris Dymek, with data. Thanks to Scott King for discussion. 1 TEXT far greater than any similar object ever discovered INTONATION L+H* !H*H- L+H* !H*L- L+H* L+!H*L-L% BROWS [ 1+2 ] HEAD [ TL ] D* U* Figure 1: Natural conversational facial displays (a, top), a high-level symbolic annotation (b, mid- dle), and a RUTH animation synthesized automatically from the annotation (c, bottom).