Pattullo Bridge Replacement Project EAC Application: Part B Section 7.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day of September 19 11

Orders in Council approved on the 2n day of September 19_11. PURPORT. 1201 Public Utilities Act - Proposed issuance of bond end debenture issues to the Pacific Power and Water Co. Ltd and its subsidiaries Quesnel Light and Power Co. Ltd., The Elk Creek Waterworks Co. Ltd and Hope Utilities Ltd. c on f iden t Orders in Council approved on the 2nd day of September , 19...39. So PURPORT. 12,:12 lacer-Yining Act - Please-mining leases Nos 96A, 102A and 106A in the Atlin Mining Division extended for a further period of 20 years, effective November 29, 1939. ■ Orders in C wpcil approved on the. 5th day of September PURPORT. 120z 1t,lic Libraries Act - Providing for the holding of a plebiscite on the withdrawal of the Mara Rural School District from the Okanagan Union Library District. 1204 Provincial Elections Act - Apptmt of Provincial Elections Commrs. 120!: -lacer-Lining Act - Consolidation of placer-mining leases in the Atlin Mining Division. 1206 Small Debts Courts - George S. McCarter of Golden, Stipendiary Magistrate in and for the County of Kootenay apptd Small Debts Courts Magistrate. 1207 ninicipal Act - Hugh H. Worthington, Justice of the Peace, of ',:nderby apptd Acting Police Magistrate of the Corporation of the City of Enderby in place of Mr. G. Rosoman during his absence owing to illness. 128 Evidence Act - Nathaniel B. Runnalls, Relief Officer, Municipality ' of Penticton apptd a Commissioner under the Act. 1209 Highway Act - Peace Arch Highway designated es an arterial highway 1210 Health - 4ptmts of Constable J.W. Todd as Marriage Commissioner and District Registrar of B.D. -

Barker Letter Books Volume 1

Barker Letter Book Volume 1 Page(s) 1 - 4 AEmilius Jarvis November 8, 1905 McKinnon Building, Toronto, Ont. Dear Sir:- None of your valued favors unanswered. I have heard nothing recently from Mr. R. Kelly regarding any action taken by Mr. Sloan, as the result of your meeting the Government. As I informed you, I called on Mr. Kelly immediately on receipt of your letter containing the memorandum of what the Government agreed to do, providing Mr. Sloan endorsed it, and the request that he wire his endorsement, or better, that he go East and stay there until the Order in Council was made. I told Mr. Kelly that our Company would guarantee any expense attached to the trip. The next day Mr. Kelly sent up for a copy of the Memorandum for Mr. Sloan: I sent it together with extracts from your letter, and asked Mr. Kelly to arrange for a meeting with Mr. Sloan, as I would like to talk over the matter with him, but have heard nothing from either Mr. Kelly or Mr. Sloan. I however, have seen both the Wallace Bros., and Mr. R. Drainey and they have seen both Kelly and Sloan, they and the Bell-Irvings have given me to understand that they have endorsed all we have said and done. I have seen Mr. Sweeny several times since his return, he seems to agree with what has been done, but seems to think the newly appointed Commission should act in the matter and that the Government will follow their recommendations. In the meantime the people who intend building at Rivers Inlet and Skeena are going ahead with their preparations. -

Order in Council 1349/1937

1349 Approved and ordered this 13th day of Novembe; A.D. 19 37 At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, LleutenantGovernor. PRESENT: 1\ The Honourable in the Chair. ki 4 Mr. Pattullo Mr. ;;eir Mr. racPherson LacDonald Mn Pearson Mn Hart Mr. Mr. Mr. Mr. Mr. To His Honour The Lieutenant-Governor in Council: The undersigned has the honour to recommend: TEAT Regulations respecting the use and operation of the Pattullo Bridge recently constructed over the Fraser River at New Westminster, pursuant to the "Fraser River (New Westminster Bridge) Act", in terms of the draft regulations attached hereto, be made pursuant to the said Act. AND FURTHER TO RECOMMEND that Regulations Nos. 1 to 11 inclusive shall take effect at 12 o'clock in the forenoon on Monday the 15th day of November, 1937, and that Regulation No. 12 shall take effect at one minute past twelve o'clock in the forenoon on Tuesday/ the 16th day of November, 1937. J,; RECOMMENDED this 6 'day of A.D. 1937. MINISTER F PUBLIC WORKS. APPROVED this oil/day of Ak0,1(4/ A.D.1937. PREL,IDING MEMBER OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. ofe. 14-7%/37; /676/37;i44/3/3i5;725/1/43;15-745D; 3 7- /5-2., a. Regulations respecting th_. use and operation of the PATTULLO BRIDGE, NEB WASMEINSTER, pursuant to Section 8 of the "Fraser River Now Westminster) Bridge Act". 1. Interpretation. In these Regulations, unle.3s the context otherwise requires, "Minister" means the sinister of Public Works, and, in respect of the granting of permits, includes any person designated by him in writing for that purpose; "Bridge" means the Pattullo highway-traffic bridge recently constructed over the Fraser River at NewWestminster, pur- suant to the "Praiser River (New Westminster) Bridge Ant," and includes its approaches from the southerly limit at intersection with Scott Road immediately south of Toll Cates to the northerly at intersection with Columbia Avenue, East and West, and LicHride Avenue. -

Advocates Push for Passenger Rail Stop in Blaine | the Northern Light

Advocates push for passenger rail stop in Blaine | The Northern Light https://web.archive.org/web/20190718003404/https://www.thenort... JJuullyy 1177,, 22001199 Bookmark This Site Advocates push for passenger rail stop in Blaine By Jami Makan Advocates of an Amtrak passenger rail stop in Blaine met over the weekend, but organizers cautioned that much work remains to be done before it becomes a reality. A meeting hosted by rail advocacy group All Aboard Washington (AAWA) took place on July 13 at the Semiahmoo Resort. The turnout was high, with many in the audience arguing that an Amtrak passenger rail stop in Blaine is long overdue. On the Amtrak Cascades service, there are currently no stops between Fairhaven Station in Bellingham and Pacific Central Station in Vancouver, B.C. The event featured presentations by Bruce Agnew, director of the Cascadia Center; Dr. Laurie Trautman, director of Western Washington University’s Border Policy Research Institute (BPRI); and others. Audience members including Blaine city manager Michael Jones, Blaine mayor Bonnie Onyon, state representative Luanne Van Werven and White Rock city councilor Scott Kristjanson also addressed the gathering. The consensus was that a rail stop in Blaine would not only serve north Whatcom County, but would also serve those living in southern B.C. According to statistics presented at the meeting, there are almost a million B.C. residents who live south of the Fraser River. “That’s bigger than Snohomish County, which has three rail stops,” said Agnew. In order to determine how many of those B.C. residents would use a Blaine rail stop, the next step is for an “investment grade” ridership 1 of 3 2/5/20, 10:23 AM Advocates push for passenger rail stop in Blaine | The Northern Light https://web.archive.org/web/20190718003404/https://www.thenort.. -

Boris Karloff in British Columbia by Greg Nesteroff

British Columbia Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation | Vol.39 No.1 2006 | $5.00 This Issue: Karloff in BC | World War One Mystery | Doctors | Prison Escapes | Books | Tokens | And more... British Columbia History British Columbia Historical Federation Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation A charitable society under the Income Tax Act Organized 31 October 1922 Published four times a year. ISSN: print 1710-7881 !online 1710-792X PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 British Columbia History welcomes stories, studies, and news items dealing with any aspect of the Under the Distinguished Patronage of Her Honour history of British Columbia, and British Columbians. The Honourable Iona Campagnolo. PC, CM, OBC Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia Please submit manuscripts for publication to the Editor, British Columbia History, Honourary President Melva Dwyer John Atkin, 921 Princess Avenue, Vancouver BC V6A 3E8 e-mail: [email protected] Officers Book reviews for British Columbia History,, AnneYandle, President 3450 West 20th Avenue, Jacqueline Gresko Vancouver BC V6S 1E4, 5931 Sandpiper Court, Richmond, BC, V7E 3P8 !!!! 604.733.6484 Phone 604.274.4383 [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] First Vice President Patricia Roy Subscription & subscription information: 602-139 Clarence St., Victoria, B.C., V8V 2J1 Alice Marwood [email protected] #311 - 45520 Knight Road Chilliwack, B. C.!!!V2R 3Z2 Second Vice President phone 604-824-1570 Bob Mukai email: [email protected] 4100 Lancelot Dr., Richmond, BC!! V7C 4S3 Phone! 604-274-6449!!! [email protected]! Subscriptions: $18.00 per year Secretary For addresses outside Canada add $10.00 Ron Hyde #20 12880 Railway Ave., Richmond, BC, V7E 6G2!!!!! Phone: 604.277.2627 Fax 604.277.2657 [email protected] Single copies of recent issues are for sale at: Recording Secretary Gordon Miller - Arrow Lakes Historical Society, Nakusp BC 1126 Morrell Circle, Nanaimo, BC, V9R 6K6 [email protected] - Book Warehouse, Granville St. -

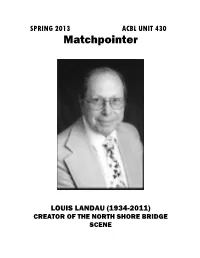

Matchpointer

SPRING 2013 ACBL UNIT 430 Matchpointer LOUIS LANDAU (1934-2011) CREATOR OF THE NORTH SHORE BRIDGE SCENE VANCOUVER UNIT 430 SPRING SECTIONAL May 10-12, 2013, Engineers Hall, 4333 Ledger Ave. Burnaby, BC Friday Afternoon May 10, 1:30 PM Open Pairs (0-750/ 750-2000/ 2000 +) 0-750 Pairs (0-100/100-300/ 300-750) Celebrity Speaker: DAN WATSON, 6:45 PM-7:15 PM Friday Evening May 10, 7:30 PM Open Pairs (0-750 /750-2000 /2000 +) 0-750 Pairs (0-100/ 100-300/300-750) Ben Lapidus Trophy Bracketed Knockout Teams (1 of 3) Saturday Afternoon May 11, 12:30 PM Open Pairs: First Session (single session (0-750/ 750-2000 /2000 +) accepted) 0-750 Pairs (0-100/ 100-300/ 300-750) Ben Lapidus Trophy Bracketed Knockout Teams (2 of 3) Unit 430 Annual General Meeting To be held immediately after the afternoon session. Members are urged to provide input and vote for new board candidates. Saturday Evening May 11, 6:30 PM Open Pairs: Final Session (single session (0-750/ 750-2000/ 2000 + ) accepted) Future Master Pairs (0-100/ 100-300/ 300-500) Ben Lapidus Trophy Bracketed Knockout Teams (3 of 3) Sunday Morning and Afternoon May 12 10:00 & TBA Flight A/X Swiss Teams (0-2000/ 2000+) Flight B/C/D Swiss Teams (0-200; 200-500; 500-1500) A short Lunch break: A box lunch is available for $5 prepaid. Partnerships: Kathy Bye, 604-320-7390; [email protected] Tournament Chairs: Chris Moore, [email protected], 604-581-0277 Clay Connolly, [email protected]; 778-839-8354 Card Fees: $11/Session ($1 discount for paid ACBL members) Stratification by average, but all players must be below the event limit. -

Historical Heritage Study

PATTULLO BRIDGE REPLACEMENT PROJECT EAC APPLICATION Note to the Reader This report was finalized before the Pattullo Bridge Replacement Project was transferred from TransLink (South Coast British Columbia Transportation Authority) to the BC Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure (MoTI). References to TransLink should be read as MoTI unless referring specifically to TransLink policies or other TransLink-related aspects. Translink Hatfield Consultants Pattullo Bridge Replacement Project Historical Heritage Study April 2018 Submitted by: Denise Cook Design Team: Denise Cook, Denise Cook Design Project contact: Denise Cook, CAHP Principal, Denise Cook Design #1601-1555 Eastern Avenue North Vancouver BC V7N 2X7 Telephone: 604-626-2710 Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 1 2.0 OBJECTIVES .................................................................................... 1 3.0 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................. 3 3.1 General Methodology ....................................................... 3 3.2 Planning and policy context .............................................. 4 4.0 HISTORICAL CONTEXT .................................................................... 4 4.1 Brief Historical Context of Bridge and Environs ............... 4 4.2 Early Land Uses ................................................................. 5 4.3 Transportation networks ............................................... -

Research Note SS Beaver on the Lower Fraser River Route, 1898

Research Note The Cruise of the Steel Steamer: SS Beaver on the Lower Fraser River Route, 1898–1926 Trevor Williams* n British Columbia, newly named vessels earn the “Beaver” mat- ronymic under the weight of great expectations. This single word swells with the spirit of colonial-era trading and exploration, arising from the first such-named vessel, the original Beaver, a steamer built in I 1835 England in and owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company. This wooden side-wheeler plied the rivers and oceans of precolonial British Columbia before being marooned upon the rocks at Prospect Point, near Vancouver, in 1870. As she rotted and was slowly looted, this much- photographed steamboat was only beginning to be transformed, through the tributes and eulogies given by historians, into a cultural icon of the frontier explo- ration and conquest of British Columbia by newcomer settlers. Because of the heritage and culture embedded within the name “Beaver,” only one paddlewheel steamer could be given the same name of this evolving cultural icon, and such a boat had to be known as a special vessel, even before it was built.1 In 1898, at Albion Iron Works, in the inner harbour of Victoria, British Columbia, “a new shipyard has sprung into existence, in which the first stern-wheeled, steel vessel ever put together in this province is to be built!” This was an unprecedented year for shipbuilding in British Columbia, where several new sternwheel boats designed to conquer the Yukon rivers were being assembled in Victoria and New Westminster. Of course, most boat builders were also woodworkers, but this new steel steamer being built for Canada Pacific Navigation (CPN) mainly needed ironworkers * Thank you to Jude Angione, Merlin Bunt, George Duddy, and John MacFarlane for their assistance. -

CN Construction Notice: June 21, 2021

Construction Notice: June 21, 2021 Construction Notice: June 21, 2021 Yale 118.7, New Westminster Rail Bridge, CN Seismic Retrofit of Rail Bridge – PER 18-218 Overview of the Project Canadian National Railway Company (CN) is completing a seismic retrofit of the rail bridge located at Mile 118.7 on the Fraser River, directly upstream of the existing Pattullo Bridge. The purpose of the project is to strengthen the substructure and foundations for increased seismic capacity. The retrofit program will require the installation of 13 new 2,750 mm diameter steel piles. Two (2) piles each will be installed at pier 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 and three (3) piles will be installed at the refurbished Protection Pier. New piles will be connected to the in-water concrete piers using steel girder collars, pile sleeves and caps. The 2,750 mm diameter piles will be driven in segments, using an impact hammer with the bulk of the work conducted from a temporary construction trestle and barges. Pattullo Bridge City of New Westminster City of Surrey Pier 10 New Westminster Bridge: Yale 118.7 Pier 9 Pier 8 Pier 7 Pier 6 and Protection Pier Fraser River Construction Notice: June 21, 2021 What you can Expect Timing Traffic Work is anticipated to start on July 6, 2021 and to be No vehicle traffic impacts are expected. completed in the fall of 2022. The overall schedule is subject to river conditions and execution of in water works in accordance with regulatory agency requirements. Hours of Work Impacts Short, intermittent periods of pile driving will occur Nearby businesses and residents may hear some over the project duration, from Monday through noise from the intermittent pile driving and may also Saturday as follows: see temporary construction lights used to illuminate • Monday – Friday 7am–8pm the work area through the night. -

THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE of the LOWER FRASER RIVER July 2014

THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE LOWER FRASER RIVER July 2014 Prepared by the Richmond Chamber of Commerce with the assistance of D.E. Park & Associates Ltd. and with the support of: Richmond Chamber of Commerce Burnaby Board of Trade Maple Ridge & Pitt Meadows Chamber of Commerce Surrey Board of Trade Greater Langley Chamber of Commerce Chilliwack Chamber of Commerce The Vancouver Board of Trade Delta Chamber of Commerce Hope & District Chamber of Commerce Tri-Cities Chamber of Commerce Mission Regional Chamber of Commerce Province of British Columbia, Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure Abbotsford Chamber of Commerce New Westminster Chamber of Commerce THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE LOWER FRASER RIVER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Recognition goes to those organizations that funded this endeavour: • Richmond Chamber of Commerce • Surrey Board of Trade • Vancouver Board of Trade • Tri-Cities Chamber of Commerce • Abbotsford Chamber of Commerce • Burnaby Board of Trade • Greater Langley Chamber of Commerce • Delta Chamber of Commerce • Mission Regional Chamber of Commerce • New Westminster Chamber of Commerce • Maple Ridge and Pitt Meadows Chamber of Commerce • Province of British Columbia, Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure Special thanks go to the report’s principal researcher and co-author, Dave Park, of D.E. Park & Associates Ltd., and to co-author Matt Pitcairn, Manager of Policy and Communications at the Richmond Chamber of Commerce, who provided extensive support in data gathering, stakeholder engagement, document preparation and drafting report sections. The experience and detailed knowledge of Allen Domaas, retired CEO of the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, has also added significantly to this report. A number of organizations and knowledgeable individuals were consulted and generously provided input and perspective to this work. -

Guidelines Short-Term Vessel Waivers

GUIDELINES SHORT-TERM VESSEL WAIVERS The Pacific Pilotage Regulations state that every vessel (or combination of vessels) over 350 gross tons (ITC) is subject to compulsory pilotage. Under Section 10(3) of the Pacific Pilotage Regulations, the Authority may waive compulsory pilotage provided that the following conditions are met: 1. The vessel is under 10,000 gross tons (ITC). 2. As of the day on which the application is made, every person in charge of the deck watch: (a) holds the certificates that are required by Part 2 of the Marine Personnel Regulations or, if the ship is not Canadian, equivalent certificates; (b) has completed, as a person in charge of the deck watch on voyages in the region, at least (i) 150 days of service in the preceding 18 months, or (ii) 365 days of service in the preceding 60 months, including at least 60 days in the preceding 24 months; and (c) has served as a person in charge of the deck watch in the compulsory pilotage area for which the waiver is sought on at least one occasion within the preceding 24 months. In addition, under PPA’s Standard of Care, an officer of the watch who navigates your vessels in BC pilotage waters must have documented trips associated with the zones for which the waiver is being sought, time which may be accumulated as any member of the deck watch under the supervision of a qualified waiver holder or pilot, as follows by zone: Zone 1 Fraser River, below the New Westminster bridge: 5 round trips Zone 2 Fraser River, above the New Westminster bridge: 10 round trips Zone 3 Second -

John Hendry and the Vancouver, Westminster and Yukon Railway: "It Would Put Us on Easy Street" PHYLLIS VEAZEY

John Hendry and the Vancouver, Westminster and Yukon Railway: "It Would Put Us on Easy Street" PHYLLIS VEAZEY For the first decade of the twentieth century John Hendry was British Columbia's foremost lumberman and leading industrialist — the first British Columbian, indeed, to be elected President of the Canadian Man ufacturers' Association (hereafter CMA). From the head office of his resource-based empire's foundation, the British Columbia Mills Timber and Trading Company (hereafter the BCMT&T) in Vancouver,1 he presided over a host of activities. One of these, the Vancouver, West minster and Yukon Railway Company (hereafter the VW&Y) has a particular interest for students of British Columbian and Canadian busi ness history, for it involved him in complex negotiations with real estate speculators, railway promoters, steamship company owners, wholesalers, manufacturers, American lumbermen and governments at the municipal, provincial and federal levels. Examining his promotion of it, therefore, sheds much light not only on one businessman's modus operandi', it also conveys a sense of the manner in which businessmen generally sought to get their way in the difficult world created by large companies, rival political parties, conflicting jurisdictions and a belief in the almost limit less opportunity open to them if they acted with speed and efficiency. What follows, in concerning itself with the politics of railway promotion as revealed by Hendry's activities on behalf of the VW&Y, has relevance for those interested in a particular type of entrepreneurial behaviour as much as it has for those desiring to know more of the structuring of the province's business life.