Historical Heritage Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigrant Demographics New Westminster, B.C. - 2018

IMMIGRANT DEMOGRAPHICS NEW WESTMINSTER, B.C. - 2018 - New Westminster Immigrant Demographics I Page 1 IMMIGRANT DEMOGRAPHICS Your quick and easy look at facts and figures around NEW WESTMINSTER immigration. Newcomers are an important and growing IMMIGRANT DEMOGRAPHICS part of your community. Here’s what you need to know. GLOSSARY OF TERMS: New Westminster is the oldest community in Metro Vancouver and is CENSUS refers to the population Census of Canada, which is taken at five-year intervals and counts located near its geographical centre. It persons and households and a wide variety of characteristics to provide a statistical portrait of the is bordered by Burnaby to the west and country. north, by Coquitlam to the east, and by the Fraser River to the south. TOTAL POPULATION refers to the total population counts in private households of a specific geographic area, regardless of immigration status. The New Westminster Public Library has IMMIGRANTS includes persons who are, or who have ever been, landed immigrants or permanent two locations. residents. In the 2016 Census of Population, ‘Immigrants’ includes immigrants who landed in Canada on or prior to May 10, 2016. RECENT IMMIGRANTS are immigrants who arrived in Canada between January 1, 2011 and May 10, 2016. METRO VANCOUVER comprises 21 municipalities, one electoral district and one First Nation located in the southwest corner of British Columbia’s mainland. It is bordered by the Strait of Georgia to the west, the U.S. border to the south, Abbotsford and Mission to the east, and unincorporated mountainous areas to the north. NOTES: ■ Total population data in each chart or table may vary slightly due to different data sources, i.e. -

Crown Lands: a History of Survey Systems

CROWN LANDS A History of Survey Systems W. A. Taylor, B.C.L.S. 1975 Registries and Titles Department Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management Victoria British Columbia 5th Reprint, 2004 4th Reprint, 1997 3rd Reprint, 1992 2nd Reprint and Edit, 1990 1st Reprint, 1981 ii To those in the Provincial Archives who have willingly supplied information, To those others who, knowingly and unknowingly, have contributed useful data, and help, and To the curious and interested who wonder why things were done as they were. W. A. Taylor, B.C.L.S. 1975 iii - CONTENTS - Page 1 Evolution of Survey Systems in British Columbia 4 First System 1851 - Hudson's Bay Company Sections. 4 Second System 1858 - Sections and Ranges Vancouver Island. 9 Third System 1858 - Sections, Ranges, Blocks. 13 Fourth System - Variable Sized District Lots. 15 Fifth System 1873 - Townships in New Westminster District. 20 Sixth System - Provincial Townships. 24 Seventh System - Island Townships. 25 Eighth System - District Lot System. 28 Ninth System - Dominion Lands. 31 General Remarks 33 Footnotes - APPENDICES - 35 Appendix A - Diary of an early surveyor, 1859. 38 Appendix B - Scale of fees, 1860. 39 Appendix C - General Survey Instructions. 40 Appendix D - E. & N. Railway Company Survey Rules, 1923. 43 Appendix E - Posting - Crown Land Surveys. 44 Appendix F - Posting - Dominion Land Surveys. 45 Appendix G - Posting - Land Registry Act Surveys. 46 Appendix H - Posting - Mineral Act Surveys. 47 Appendix I - Official Map Acts. 49 Appendix J - Lineal and Square Measure. iv - LIST OF PLATES - Page 2 Events Affecting Early Survey Systems 5 Plate 1. Victoria District Official Map. -

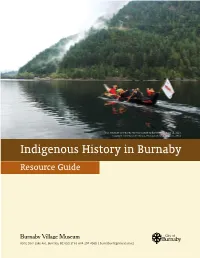

Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide

Tsleil-Waututh community members paddling Burrard Inlet, June 18, 2014. Copyright Tsleil-Waututh Nation, Photograph by Blake Evans, 2014. Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide 6501 Deer Lake Ave, Burnaby, BC V5G 3T6 | 604-297-4565 | burnabyvillagemuseum.ca 2019-06-03 The Burnaby School District is thankful to work, play and learn on the traditional territories of the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwxwú7mesẖ speaking people. As we inquire into learning more about the history of these lands, we are grateful to Burnaby Village Museum for working with our host First Nation communities. The knowledge being shared in this resource guide through our local communities supports the teaching and learning happening in our classrooms. It deepens our understanding of the history of our community and will increase our collective knowledge of our host First Nations communities’ history in Burnaby. In our schools, this guide will assist in creating place-based learning opportunities that will build pride for our Indigenous learners through the sharing of this local knowledge, but also increase understanding for our non-Indigenous learners. Through this guide, we can move closer to the Truth and Reconciliation’s Call to Action 63 (i and iii): 63. We call upon the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada to maintain an annual commitment to Indigenous education issues, including: i. Developing and implementing Kindergarten to Grade Twelve curriculum and learning resources on Indigenous peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools. iii. Building student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy, and mutual respect. We would like extend thanks to Burnaby Village Museum staff for their time and efforts in creating this resource guide. -

Order in Council 282/1981

BRITISH COLUMBIA 282 APPROVED AND ORDERED -4.1981 JFL ieutenant-Governor EXECUTIVE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, VICTORIA FEB. -4.1981 On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant-Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that the trans fer of the interest of the Crown in the lands, equipment and property in items 6, 11 and 15 in the Schedule' titled Victoria Land Registration District in order in council 1131/79Jis resc inded. Provincial Secretary and Minister of Government Services Presiding Member of t ye Council ( Thu part ii for administrative purposes and is riot part o/ the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: British Columbia Buildings Corporation Act, a. 15 Act and section Other (specify) R. J. Chamut Statutory authority checked by . .... ...... _ _ . .... (Signature and typed or firtnWd name of Legal °Aker) January 26, 1981 4 2/81 1131 APPROVED AND ORDERED Apa ion 444114,w-4- u EXECUTIVE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, VICTORIA kpR. 121979 On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant-Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that 1. the Lands listed on the Schedules attached hereto be hereby transferred to the British Columbia Buildings Corporation together with all equipment, movable and immovable property as may be on or related to the said Lands belonging to the Crown. 2. the Registrar of the Land Registry Office concerned, on receipt of a certified copy of this Order—in—Council, make all necessary amendments to the register as required under Section 14(2) of the British Columbia Buildings Corporation Act. -

Day of September 19 11

Orders in Council approved on the 2n day of September 19_11. PURPORT. 1201 Public Utilities Act - Proposed issuance of bond end debenture issues to the Pacific Power and Water Co. Ltd and its subsidiaries Quesnel Light and Power Co. Ltd., The Elk Creek Waterworks Co. Ltd and Hope Utilities Ltd. c on f iden t Orders in Council approved on the 2nd day of September , 19...39. So PURPORT. 12,:12 lacer-Yining Act - Please-mining leases Nos 96A, 102A and 106A in the Atlin Mining Division extended for a further period of 20 years, effective November 29, 1939. ■ Orders in C wpcil approved on the. 5th day of September PURPORT. 120z 1t,lic Libraries Act - Providing for the holding of a plebiscite on the withdrawal of the Mara Rural School District from the Okanagan Union Library District. 1204 Provincial Elections Act - Apptmt of Provincial Elections Commrs. 120!: -lacer-Lining Act - Consolidation of placer-mining leases in the Atlin Mining Division. 1206 Small Debts Courts - George S. McCarter of Golden, Stipendiary Magistrate in and for the County of Kootenay apptd Small Debts Courts Magistrate. 1207 ninicipal Act - Hugh H. Worthington, Justice of the Peace, of ',:nderby apptd Acting Police Magistrate of the Corporation of the City of Enderby in place of Mr. G. Rosoman during his absence owing to illness. 128 Evidence Act - Nathaniel B. Runnalls, Relief Officer, Municipality ' of Penticton apptd a Commissioner under the Act. 1209 Highway Act - Peace Arch Highway designated es an arterial highway 1210 Health - 4ptmts of Constable J.W. Todd as Marriage Commissioner and District Registrar of B.D. -

Barker Letter Books Volume 1

Barker Letter Book Volume 1 Page(s) 1 - 4 AEmilius Jarvis November 8, 1905 McKinnon Building, Toronto, Ont. Dear Sir:- None of your valued favors unanswered. I have heard nothing recently from Mr. R. Kelly regarding any action taken by Mr. Sloan, as the result of your meeting the Government. As I informed you, I called on Mr. Kelly immediately on receipt of your letter containing the memorandum of what the Government agreed to do, providing Mr. Sloan endorsed it, and the request that he wire his endorsement, or better, that he go East and stay there until the Order in Council was made. I told Mr. Kelly that our Company would guarantee any expense attached to the trip. The next day Mr. Kelly sent up for a copy of the Memorandum for Mr. Sloan: I sent it together with extracts from your letter, and asked Mr. Kelly to arrange for a meeting with Mr. Sloan, as I would like to talk over the matter with him, but have heard nothing from either Mr. Kelly or Mr. Sloan. I however, have seen both the Wallace Bros., and Mr. R. Drainey and they have seen both Kelly and Sloan, they and the Bell-Irvings have given me to understand that they have endorsed all we have said and done. I have seen Mr. Sweeny several times since his return, he seems to agree with what has been done, but seems to think the newly appointed Commission should act in the matter and that the Government will follow their recommendations. In the meantime the people who intend building at Rivers Inlet and Skeena are going ahead with their preparations. -

10472 Scott Road, Surrey, BC

FOR SALE 10472 Scott Road, Surrey, BC 3.68 ACRE INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT PROPERTY WITH DIRECT ACCESS TO THE SOUTH FRASER PERIMETER ROAD PATULLO BRIDGE KING GEORGE BOULEVARD SOUTH FRASER PERIMETER ROAD (HIGHWAY #17) 10472 SCOTT ROAD TANNERY ROAD SCOTT ROAD 104 AVENUE Location The subject property is located on the corner of Scott Road and 104 Avenue, situated in the South Westminster area of Surrey, British Columbia. This location benefits from direct access to the South Fraser Perimeter Road (Highway #17) which connects to all locations in Metro Vancouver via Highways 1, 91, and 99. The location also provides convenient access south to the U.S. border, which is a 45 minute drive away via the SFPR and either Highway 1 or Highway 91. The property is surrounded by a variety of restaurants and neighbours, such as Williams Machinery, BA Robinson, Frito Lay, Lordco, Texcan and the Home Depot. SCOTT ROAD Opportunity A rare opportunity to acquire a large corner Scott Road frontage property that has been preloaded and has a development permit at third reading for a 69,400 SF warehouse. 104 AVENUE Buntzen Lake Capilano Lake West Vancouver rm A n ia North d n I 99 Vancouver BC RAIL Pitt Lake 1 Harrison Lake Bridge Lions Gate Ir o Port Moody n 99 W o PORT METRO r VANCOUVER Burrard Inlet k e r s M e m o r i a l B C.P.R. English Bay r i d g e 7A Stave Lake Port Coquitlam Vancouver Maple Ridge 7 Key Features CP INTERMODAL Coquitlam 7 1 7 9 Burnaby Pitt 7 Meadows 7 VANCOUVER P o r t M a C.P.R. -

9930 197Th Street, Langley, Bc Port Kells Industrial Area

FOR SALE 14.54 ACRE INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE 9930 197TH STREET, LANGLEY, BC PORT KELLS INDUSTRIAL AREA GOLDEN EARS BRIDGE GOLDEN EARS WAY CHRIS MACCAULEY JOE INKSTER PERSONAL REAL ESTATE CORPORATION PERSONAL REAL ESTATE CORPORATION 604.662.5190 604.662.5134 [email protected] [email protected] OPPORTUNITY CBRE has been engaged by Trimac Transportation to facilitate this exceedingly rare opportunity to list for sale industrial land in Metro Vancouver. THE LOCATION The subject property is located in the well established Port Kells industrial area, and is considered the Industrial Hub of the lower mainland. Port Kells (781.1 acres) is located on the border of Surrey and Langley, on the south side of the Fraser River, north of Highway 1 and east of Highway 15. The industrial lands are in high demand due to the area’s strategic location within Metro Vancouver and access to key transportation corridors including the east/west Highway 1 and the north/south Highway 15 that provides a direct link to the US commercial border crossing. The South Fraser CIVIL & LEGAL ADDRESSES Perimeter Road (SFPR) provides excellent access to the port, the gateway to Asia Pacific. Port Kells is home to a diverse range of industries with a high 9930 197TH STREET, LANGLEY, BC concentration of manufacturing, PID: 001-618-148 PARCEL A (Y68082) DISTRICT LOT 122 GROUP 2 NEW WESTMINSTERDISTRICT PLAN 54498 TENANCY Lafarge Canada currently leases 4.013 acres from Trimac Transportation. SITE SIZE Trimac Transportation will also consider a leaseback of the property. 14.54 ACRES PROPERTY TAXES (2018) SUBMISSION GUIDELINE $349,755.40 Potential purchasers that require access to additional information such as environmental documents, site plans, purchase and sale agreement, leases, and leaseback agreement, must complete the non-disclosure agreement. -

Winter 2004 Volume 18

CON TROVERSY LOOKOUT #18 • a forum for writers 3516 W. 13th Ave., Vancouver, BC V6R 2S3 LOOKOUTLOOKOUTLOOKOUT s Richard Heinberg recounts in Power A Down: Options and Actions for a Post- Petroleum is Carbon World (New Society $22.95), America was the world’s foremost oil producer during the period when mankind evolved from ox carts to jet planes. For much of that century, USSR production of oil ranked second. $ According to Heinberg, oil discovery in America peaked in the 1930s; its oil pro- water. You notice now that the raft is surrounded by many sound-looking canoes, each duction peaked around 1970; but by then America hadP established its linksO with the carrying aWER family of indigenous fishers. Men on the raft are systematically forcing peo- Middle East for oil imports. Soviet oil production peaked in 1987. During the Eight- ple out of the canoes and onto the raft at gunpoint, and shooting holes in the bottoms ies, the CIA fomented proxy wars in Soviet territories (i.e. Osama bin Laden in Af- of the canoes. This is clearly insane behaviour: the canoes are the only possible sources ghanistan) and Saudi Arabia was persuaded to flood the world oil market with cheap of escape or rescue if the raft goes down, and taking more people on board the already oil. The Soviet Union crumbled. overcrowded raft is gradually bringing its deck even with the water line. You reckon The lone superpower left standing was determined to keep it that way. “If, instead that there must now be four hundred souls aboard. -

Comparing Municipal Government Finances in Metro Vancouver

Comparing Municipal Government Finances in Metro Vancouver October 2014 WEST DISTRICT OF VANCOUVER NORTH VANCOUVER CITY OF NORTH VANCOUVER COQUITLAM PORT MOODY BURNABY PORT COQUITLAM VANCOUVER PITT MAPLE MEADOWS RIDGE NEW WESTMINSTER RICHMOND DISTRICT OF LANGLEY DELTA SURREY CITY OF LANGLEY WHITE ROCK Charles Lammam, Joel Emes, and Hugh MacIntyre fraserinstitute.org Contents Summary / iii Introduction / 1 1 Background / 3 2 Municipal Spending / 7 3 Municipal Revenue / 15 4 Municipal Debt and Interest Expenditures / 35 Conclusion / 39 Appendix 1 Description of the Local Government Statistics / 41 Appendix 2 Spending and Revenue per Person by Major Category / 45 Appendix 3 Municipal Summary Profiles, 2012 / 47 References / 56 About the Authors / 59 Publishing Information 60 Acknowledgments / 60 Supporting the Fraser Institute 61 Purpose, Funding, and Independence / 62 About the Fraser Institute / 63 Editorial Advisory Board / 64 fraserinstitute.org / i fraserinstitute.org Summary Municipal governments play an important role in the lives of British Columbians by providing important services and collecting taxes. But municipal finances do not receive the same degree of public scrutiny as more senior governments. This can pose a problem for taxpayers and voters who want to understand how their municipal government performs, especially compared to other municipalities. To help create awareness and encourage debate, this report provides a summary analysis of important financial information for 17 of the 21 municipal- ities in Metro Vancouver, spanning a 10-year period (2002–2012). The intention is not to make an assessment of any municipality’s finances—for instance, whether taxes or spending are too high or whether municipal governments produce good value for taxpayers. -

SURREY RELOCATION GUIDE: Doing Business in Surrey

SURREY BOARD OF TRADE FURTHERING THE INTERESTS OF BUSINESSES SINCE 1918 Surrey Board of Trade SURREY RELOCATION GUIDE: Doing Business in Surrey Surrey Board of Trade supports and attracts companies by: ■ Providing data on all aspects of local ■ Connecting universities and colleges that infrastructure including highway and air offer customized training programs for new connections, human capital and commercial workers to match industry needs to curriculum real estate. development. ■ Identifying real estate options including ■ Providing information and facilitating contacts office space for new building construction in with federal, provincial & local authorities. collaboration with local real estate firms. Exploring financial incentive programs and ■ Business match-making. venture capital programs. ■ Developing contacts with foreign-owned ■ Conducting city tours. companies. businessinsurrey.com SURREY BOARD OF TRADE Overview Surrey’s business landscape, growth opportunities and why it’s a prime location for businesses urrey is known for being one thing: WHERE SURREY STANDS WITHIN METRO VANCOUVER a powerful, Population by each municipality in Metro Vancouver (2011 v. 2015) progressive economic engine of Metro Vancouver in which to do business and invest. SIt could be the largest city in British Columbia in the next 20 years. Surrey’s population, which currently sits at almost 520,000, is projected to increase by an additional 250,000 people in the next 30 years. By 2041, one in five Metro Vancouver residents will live in Surrey. It has the highest median family income, it is centrally located between the commercial hub of Vancouver and the U.S. border (in fact, Surrey is a U.S. border city) and it is close to two international airports. -

Pattullo Bridge Replacement

L P PATTULLO BRIDGE REPLACEMENT Date: Monday, July 15, 2013 Location: Annacis Room Time: 4:15 - 4:45 pm Presentation: Steven Lan, Director of Engineering Background Materials: Memorandum from the Director of Engineering dated July 9, 2013. i. MEMORANDUM The Corporation of Delta Engineering To: Mayor and Council From: Steven Lan, P.Eng., Director of Engineerin g Date: July 9, 201 3 Subject: Council Workshop: Pattullo Bri dge Replacement File No.: 1220·20/PATT CC: George V. Harvi e, Chief Administrative Officer TransLink recently completed the initial round of public consultation sessions in New Westminster and Surrey to solicit feedback from the public on the Pattullo Bridge. A number of alternative crossings were developed for three possible corridors: 1. Existing Pattullo Bridge Corridor 2. Sapperton Bar Corridor • New crossing located east of the existing Pattullo Bridge that would provide a more direct connection between Surrey and Coquitlam 3. Tree Island Corridor • New crossing located west of the existing Pattullo Bridge that would essentially function as an alternative to the Queensborough Bridge Based on the initial screening work that has been undertaken, six alternatives have been identified for further consideration: 1. Pattullo Bridge Corridor - Rehabilitated Bridge (3 lanes) 2. Pattullo Bridge Corridor - Rehabilitated Bridge (4 lanes) 3. Pattullo Bridge Corridor - New Bridge (4 lanes) 4. Pattullo Bridge Corridor - New Bridge (5 lanes) 5. Pattullo Bridge Corridor - New Bridge (6 lanes) 6. Sapperton Bar Corridor - New Bridge (4 lanes) coupled with Rehabilitated Pattullo Bridge (2-3 lanes) Options involving a new bridge are based on the implementation of user based charges (tolls) to help pay for the bridge upgrades.