Jai-Bhim Lal-Salaam”: the Language of Student Protest in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Media and Film Studies Annual Report 2019-2020

Department of Media and Film Studies Annual Report 2019-2020 - 1 - Introduction The Media Studies department at Ashoka University is led by journalists, commentators, researchers, academics and investigative reporters who have wide experience in teaching, reporting, writing and broadcasting. The academic team led by Professor Vaiju Naravane, teaches approximately 25 audio- visual and writing elective courses in a given academic year in the Undergraduate Programme. These range from news writing, audio-visual production, social media, media metrics, film appreciation and cinema, digital storytelling to specialized courses in research methodology, political coverage and business journalism. In a spirit of interdisciplinarity, these courses are cross-listed with other departments like Computer Science, Creative Writing, Political Science or Sociology. The Media Studies department also collaborates with the Centre for Social and Behaviour Change to produce meaningful communication messaging to further development goals. The academic year 2019/2020 was rich in terms of the variety and breadth of courses offered and an enrolment of 130 students from UG to ASP and MLS. Several YIF students also audited our courses. Besides academics, the department also held colloquia on various aspects of the media that explored subjects like disinformation and fake news, hate speech, changing business models in the media, cybersecurity and media law, rural journalism, journalism and the environment, or how the media covers rape and sexual harassment. Faculty published widely, were invited speakers at conferences and events and also won recognition and awards. The department organized field trips that allowed students to hone their journalistic and film-making skills in real life situations. Several graduating students found employment in notable mainstream media organisations and production hubs whilst others pursued postgraduate studies at prestigious international universities. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=4... Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada India: Treatment of Dalits by society and authorities; availability of state protection (2016- January 2020) 1. Overview According to sources, the term Dalit means "'broken'" or "'oppressed'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). Sources indicate that this group was formerly referred to as "'untouchables'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). They are referred to officially as "Scheduled Castes" (India 13 July 2006, 1; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). The Indian National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) identified that Scheduled Castes are communities that "were suffering from extreme social, educational and economic backwardness arising out of [the] age-old practice of untouchability" (India 13 July 2006, 1). The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) [1] indicates that the list of groups officially recognized as Scheduled Castes, which can be modified by the Parliament, varies from one state to another, and can even vary among districts within a state (CHRI 2018, 15). According to the 2011 Census of India [the most recent census (World Population Review [2019])], the Scheduled Castes represent 16.6 percent of the total Indian population, or 201,378,086 persons, of which 76.4 percent are in rural areas (India 2011). The census further indicates that the Scheduled Castes constitute 18.5 percent of the total rural population, and 12.6 percent of the total urban population in India (India 2011). -

Mr #Ramnathkovind the President of India of #Modigovt

Mr #RamNathKovind the President of India of #ModiGovt: #RogueIAS of #ModiGovt be Publicly Hanged at the Entrance of Supreme Court of India for Crime of Misuse of Positional Power to Overnight Transfer the Chief Secretary to Govt of West Bengal. I am Babubhai Vaghela from Ahmedabad on Signal and Whatsapp Number 9409475783. Thanks.$ 1 message Babubhai Vaghela <[email protected]> Mon, 31 May 2021 at 4:06 pm To: Prez <presidentofi[email protected]> Cc: BDVY <[email protected]>, IAS Rajiv Gauba <[email protected]>, [email protected], RajivGauba CS to GOI <[email protected]>, Kumar Arun India Heritage USA <[email protected]>, arunaroy <[email protected]>, GHAA1 Yatin Oza <[email protected]>, Prashant Bhushan <[email protected]>, Tushar Mehta <[email protected]>, [email protected], krishnkant unadkat <[email protected]>, KKNiralaIAS <[email protected]>, KKVenu Madan Prasad Clerk <[email protected]>, Jitendra Singh MoS PMO <[email protected]>, PRO Pranav Patel <pro-collector- [email protected]>, PMF <kirjaamo@vnk.fi>, PMCanada Justin Trudeau <[email protected]>, PMN <[email protected]>, PMAustralia <[email protected]>, PMD <[email protected]>, PMCanada <[email protected]>, AMMF <[email protected]>, Mukesh Ambani <[email protected]>, Mamlatdar Vejlpur <[email protected]>, Nita Ambani <[email protected]>, Mamlatdar Lakhtar VB Patel <[email protected]>, RIL Paresh Davey Vraj 9099002828 <[email protected]>, so-d- [email protected], Vejalpur BJP MLA Kishor Chauhan 9879605844 <[email protected]>, -

Petition (Civil) No

5 IN THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI AT NEW DELHI (EXTAORDINARY CIVIL ORIGNAL JURISDICTION) Writ Petition (Civil) No. _________ of 2021 IN THE MATTER OF: FOUNDATION FOR INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM & ORS …Petitioners Versus UNION OF INDIA & ANR …Respondents MEMO OF PARTIES 1. Foundation For Independent Journalism Through its Director & Founding Editor, ‘The Wire’, Mr. M.K. Venu Having Registered Address At K-2, Bk Dutt Colony, New Delhi South Delhi Dl 110003 2. Mangalam Kesavan Venu S/O (Late) Mangalam Parameswaran, Director, Foundation For Independent Journalism having its Registered Address At K-2, B K Dutt Colony, New Delhi – 110003 3. Dhanya Rajendran Founder & Editor-In-Chief The News Minute Spunklane Media Pvt Ltd No 6, Sbi Road (Madras Bank Road) Bengaluru- 560001 …Petitioners Versus 6 1. Union Of India Through The Secretary (MEITY) Ministry Of Electronics And Information Technology Electronics Niketan, 6, Cgo Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi – 110003 2. Secretary, Ministry Of Information & Broadcasting Shastri Bhavan New Delhi - 110001 …Respondents FILED BY: - Filed on:- 06.03.2021 Place: - New DelhI PRASANNA S, VINOOTHNA VINJAM & BHARAT GUPTA ADVOCATES FOR THE PETITIONERS 7 SYNOPSIS The present Petition challenges the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (“IT Rules, 2021” or “Impugned Rules”) as being ultra vires the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“parent Act”), in as much as they set up a classification of ‘publishers of news and current affairs content’ (“digital news portals”) as part of ‘digital media’, and seek to regulate these news portals under Part III of the Rules (“Impugned Part”) by imposing Government oversight and a ‘Code of Ethics’, which stipulates such vague conditions as ‘good taste’, ‘decency’ etc. -

India's 2019 National Election and Implications for U.S. Interests

India’s 2019 National Election and Implications for U.S. Interests June 28, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45807 SUMMARY R45807 India’s 2019 National Election and Implications June 28, 2019 for U.S. Interests K. Alan Kronstadt India, a federal republic and the world’s most populous democracy, held elections to seat a new Specialist in South Asian lower house of parliament in April and May of 2019. Estimates suggest that more than two-thirds Affairs of the country’s nearly 900 million eligible voters participated. The 545-seat Lok Sabha (People’s House) is seated every five years, and the results saw a return to power of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who was chief minister of the west Indian state of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014. Modi’s party won decisively—it now holds 56% of Lok Sabha seats and Modi became the first Indian leader to win consecutive majorities since Indira Gandhi in 1971. The United States and India have been pursuing an expansive strategic partnership since 2005. The Trump Administration and many in the U.S. Congress welcomed Modi’s return to power for another five-year term. Successive U.S. Presidents have deemed India’s growing power and influence a boon to U.S. interests in Asia and globally, not least in the context of balancing against China’s increasing assertiveness. India is often called a preeminent actor in the Trump Administration’s strategy for a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” Yet there are potential stumbling blocks to continued development of the partnership. -

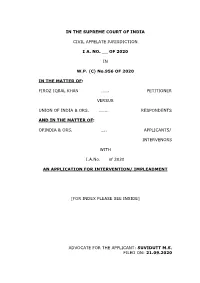

Impleadment Application

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELATE JURISDICTION I A. NO. __ OF 2020 IN W.P. (C) No.956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: OPINDIA & ORS. ….. APPLICANTS/ INTERVENORS WITH I.A.No. of 2020 AN APPLICATION FOR INTERVENTION/ IMPLEADMENT [FOR INDEX PLEASE SEE INSIDE] ADVOCATE FOR THE APPLICANT: SUVIDUTT M.S. FILED ON: 21.09.2020 INDEX S.NO PARTICULARS PAGES 1. Application for Intervention/ 1 — 21 Impleadment with Affidavit 2. Application for Exemption from filing 22 – 24 Notarized Affidavit with Affidavit 3. ANNEXURE – A 1 25 – 26 A true copy of the order of this Hon’ble Court in W.P. (C) No.956/ 2020 dated 18.09.2020 4. ANNEXURE – A 2 27 – 76 A true copy the Report titled “A Study on Contemporary Standards in Religious Reporting by Mass Media” 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION I.A. No. OF 2020 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) No. 956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1. OPINDIA THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, C/O AADHYAASI MEDIA & CONTENT SERVICES PVT LTD, DA 16, SFS FLATS, SHALIMAR BAGH, NEW DELHI – 110088 DELHI ….. APPLICANT NO.1 2. INDIC COLLECTIVE TRUST, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, 2 5E, BHARAT GANGA APARTMENTS, MAHALAKSHMI NAGAR, 4TH CROSS STREET, ADAMBAKKAM, CHENNAI – 600 088 TAMIL NADU ….. APPLICANT NO.2 3. UPWORD FOUNDATION, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, L-97/98, GROUND FLOOR, LAJPAT NAGAR-II, NEW DELHI- 110024 DELHI …. -

Democracy in the Balance

DEMOCRACY IN THE BALANCE August 13, 2020 at 4:00pm Hawaii Speaker Biographies Khaldoun BARGHOUTI Israeli Affairs Editor, Alhayat Aljadida, Ramallah, Palestine @KHBarghouti Khaldoun Barghouti is a Palestinian journalist and Israeli affairs editor for the Alhayat Aljadida newspaper in Ramallah. He also hosts a daily radio program on Ajyal Radio Network where he reviews Israeli news. In addition, Mr. Barghouti contributes analysis of Israeli events and news to a quarterly research publication for the P.L.O. Research Center. He will soon join The Palestinian Forum for Israeli Studies as a permanent writer. Mr. Barghouti previously worked as a project coordinator at Birzeit University Media Development Center and was named a fellow of the East-West Center Senior Journalists Seminar in 2014. He holds a master’s in Israeli studies from Al-Quds University and a bachelor’s in journalism from Birzeit University. Lillian CUNNINGHAM Creator and Host “Presidential” and “Constitutional” podcasts, The Washington Post, Washington, DC, USA @lily_cunningham Lillian Cunningham is a journalist with The Washington Post, focusing on American politics and history. She is the creator and host of three of The Post’s most popular podcasts: “Presidential,” “Constitutional” and “Moonrise.” “Presidential” explored the past leadership and current legacy of each American president, through interviews, reporting and research into their administrations. Previously a feature writer for and editor of The Washington Post's On Leadership section, Ms. Cunningham received two Emmy Awards for her interviews with leaders in politics, business and the arts. Additionally, she is a Webby Award honoree, an Academy of Podcasters finalist, and a former Jefferson Fellow with the East-West Center. -

Reel to Realpolitik: the Golden Years of Indian Cinema Overseas

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 10 Issue 5 Ser. II || May 2021 || PP 09-16 Reel To Realpolitik: The Golden Years Of Indian Cinema Overseas Saumya Singh School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India ABSTRACT This paper seeks to establish the links between cinema and foreign policy of a state. An important illustration is the popular reception of Bollywood abroad in the heydays of cold war. In a world simmering with tensions, the nascent film industry of India reflected the crisis of existence that its newly independent state faced. The imagination of India seeped into the consciousness of the country’s artistic, cultural, political and social scene. Bollywood had produced the best movies like Awaara and Mother India with stars such as Raj Kapoor and Nargis winning the hearts of Turkish, Russians and Nigerians alike. The aim here is to connect the acceptance of Indian cinema in the corners of the world during the 1950s and 1960s as a success of the idea of third world. Now, in a multipolar order, when India seeks to acquire a global ascendancy, it can judiciously conceive it's hard and soft power resources to woo the world. Taking cue from history, we propose a cautious utilisation of cultural resources for foreign policy ends. KEYWORDS- soft power, diplomacy, foreign policy, Bollywood, Indian Culture --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 08-05-2021 Date of Acceptance: 22-05-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION The aim of this paper is to study how Bollywood functioned as a tool of promoting India’s soft power interests in the decade of 1950’s and 1960’s. -

Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India (P Ilbu Sh Tniojde Llyy Iw Tthh I

REUTERS INSTITUTE for the STUDY of SELECTED RISJ PUBLICCATIONSATIONSS REPORT JOURNALISM Abdalla Hassan Raymond Kuhn and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (eds) Media, Reevvolution, and Politics in Egyyppt: The Story of an Po lacitil Journalism in Transition: Western Europe in a Uprising Comparative Perspective (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri (published tnioj llyy htiw I.B.Tau s)ri Robert G. Picard (ed.) Nigel Bowles, James T. Hamilton, David A. L. Levvyy )sde( The Euro Crisis in the Media: Journalistic Coverage of Transparenccyy in Politics and the Media: Accountability and Economic Crisis and European Institutions Open Government (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tauris) (published tnioj llyy htiw I.B.Tau s)ri Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (ed.) Julian Pettl ye (e ).d Loc Jla naour lism: The Decli ofne News pepa rs and the Media and Public Shaming: Drawing the Boundaries of Rise of Digital Media Di usolcs re Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri (publ(publ si heed joi tn llyy tiw h II.. T.B aur )si Wendy N. Wy de(tta .) La ar Fi le dden The Ethics of Journalism: Individual, stIn itutional and Regulating ffoor Trust in Journalism: Standards Regulation Cu nIlarutl fflluences in the Age of Blended Media (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri Arijit Sen and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen David A. L eL. vvyy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (eds) The Changing Business of Journalism and its Implications for Demo arc ccyy May 2016 CHALLENGES Robert G. Picard and Hannah Storm Nick Fras re The Kidnapping of Journalists: Reporting -

“Shoot the Traitors” WATCH Discrimination Against Muslims Under India’S New Citizenship Policy

HUMAN RIGHTS “Shoot the Traitors” WATCH Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy “Shoot the Traitors” Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8202 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8202 “Shoot the Traitors” Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 An Inherently Discriminatory -

A Peek Into Ahmedabad's Soul – a Female Perspective

A Peek Into Ahmedabad's Soul – A Female Perspective Notebook: office Created: 08-Oct-18 12:04 PM URL: https://thewire.in/urban/a-peak-into-ahmedabads-soul-a-female-perspective URBAN A Peek Into Ahmedabad's Soul – A Female Perspective A look at contemporary Ahmedabad's cultural fabric, its violence, its poets, its food culture, its queer movement and the usage of religiosity by women to resist marginalisation. Credit: YouTube Sharik Laliwala 92 interactions B O O K S C O M M U N A L I S M L G B T Q I A + U R B A N W O M E N 30/SEP/2018 The first part of this series dealt with broad movements in Ahmedabad’s history until India’s independence in 1947 keeping in mind and reviewing Saroop Dhruv’s recent work in Gujarati, Shahernama (Darshan, 2018). The second article outlined the post-colonial journey of Ahmedabad while continuing to examine Shahernama. This article reviews selected themes covered in Seminar magazine’s July 2018 issue titled ‘Ahmedabad: the city & her soul’. How do women imagine a city? What are the ways in which they can claim its public spaces? Seminar magazine’s July 2018 issue titled ‘Ahmedabad: The city & her soul’ is rooted in addressing these concerns by placing perspectives by women at the centre-stage of scholarly discourse of visualising Ahmedabad, as its editor Harmony Siganporia proposes. In this piece, I review themes covered in a selected set of articles from this issue by all-women writers who have spent (at least) some period of their lives in the city. -

Rohingyas in India State of Rohingya Muslims in India in Absence of Refugee Law

© File photo, open source Rohingyas in India State of Rohingya Muslims in India in absence of Refugee Law ©Report by Stichting the London Story Kvk 77721306; The Netherland [email protected] www.thelondonstory.org Twitter 1 Foundation London Story is a registered NGO based in Netherlands with a wide network of friends and colleagues working in India. Our focus lies in documenting hate speech and hate crimes against Indian minorities. The report on Rohingya report was prepared by Ms. Snehal Dote with inputs from Dr. Ritumbra Manuvie (corresponding author). The report was internally reviewed for editorial and content sanctity. The facts expressed in the report are sourced from reliable sources and checked for their authenticity. The opinions and interpretations are attributed to the authors alone and the Foundation can not be held liable for the same. Foundation London Story retains all copyrights for this report under a CC license. For concerns and further information, you can reach us out at [email protected] 2 Contents Background ........................................................................................................... 3 Data ....................................................................................................................... 3 India’s International Law Obligations .................................................................... 4 Timeline of Neglect and Discrimination on Grounds of Religion ..................... 5 Rationalizing exclusion, neglect, and dehumanizing of Rohingyas........................