Petition (Civil) No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India's Starvation Measures

Pandemic—4 n. r. musahar INDIA’S STARVATION MEASURES ndia is currently in the early stages of a three-week lockdown imposed by the Modi government to control the covid-19 pan- demic. National and state borders have been sealed and swathes of the economy shut down.1 Workers have been laid off and day Ilabourers have lost their incomes. Sanitation workers and other key employees are struggling to get to work without public transport. Those in the informal sector have been particularly hard hit. Migrant workers are desperately trying to return to their villages, in some cases walking hundreds of miles along now empty highways, carrying their children in their arms. Students, too, are trying to get home as their colleges and universities have shut. Those who succeed may be carrying the virus into areas of rural India it has not so far reached. But for many the dis- tances are just too great and they are stuck without an income, facing hunger in the cities that will no longer support them. The ngo sector is trying to step in, and some local-government agencies are supplying food and shelter. But the risk of overcrowding and the spread of disease imperils such interventions. Meanwhile, a combination of disrupted supply chains and panic buy- ing has led to empty shelves in shops. Food prices have risen and some commodities are unavailable. It did not take long for stories of lock- down-related violence to emerge: social media—and increasingly, the mainstream media too—is awash with evidence of the police assaulting people for supposed infractions: shoppers trying to buy essential goods, delivery staff, journalists, doctors and transport workers. -

Department of Media and Film Studies Annual Report 2019-2020

Department of Media and Film Studies Annual Report 2019-2020 - 1 - Introduction The Media Studies department at Ashoka University is led by journalists, commentators, researchers, academics and investigative reporters who have wide experience in teaching, reporting, writing and broadcasting. The academic team led by Professor Vaiju Naravane, teaches approximately 25 audio- visual and writing elective courses in a given academic year in the Undergraduate Programme. These range from news writing, audio-visual production, social media, media metrics, film appreciation and cinema, digital storytelling to specialized courses in research methodology, political coverage and business journalism. In a spirit of interdisciplinarity, these courses are cross-listed with other departments like Computer Science, Creative Writing, Political Science or Sociology. The Media Studies department also collaborates with the Centre for Social and Behaviour Change to produce meaningful communication messaging to further development goals. The academic year 2019/2020 was rich in terms of the variety and breadth of courses offered and an enrolment of 130 students from UG to ASP and MLS. Several YIF students also audited our courses. Besides academics, the department also held colloquia on various aspects of the media that explored subjects like disinformation and fake news, hate speech, changing business models in the media, cybersecurity and media law, rural journalism, journalism and the environment, or how the media covers rape and sexual harassment. Faculty published widely, were invited speakers at conferences and events and also won recognition and awards. The department organized field trips that allowed students to hone their journalistic and film-making skills in real life situations. Several graduating students found employment in notable mainstream media organisations and production hubs whilst others pursued postgraduate studies at prestigious international universities. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=4... Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada India: Treatment of Dalits by society and authorities; availability of state protection (2016- January 2020) 1. Overview According to sources, the term Dalit means "'broken'" or "'oppressed'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). Sources indicate that this group was formerly referred to as "'untouchables'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). They are referred to officially as "Scheduled Castes" (India 13 July 2006, 1; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). The Indian National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) identified that Scheduled Castes are communities that "were suffering from extreme social, educational and economic backwardness arising out of [the] age-old practice of untouchability" (India 13 July 2006, 1). The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) [1] indicates that the list of groups officially recognized as Scheduled Castes, which can be modified by the Parliament, varies from one state to another, and can even vary among districts within a state (CHRI 2018, 15). According to the 2011 Census of India [the most recent census (World Population Review [2019])], the Scheduled Castes represent 16.6 percent of the total Indian population, or 201,378,086 persons, of which 76.4 percent are in rural areas (India 2011). The census further indicates that the Scheduled Castes constitute 18.5 percent of the total rural population, and 12.6 percent of the total urban population in India (India 2011). -

Mr #Ramnathkovind the President of India of #Modigovt

Mr #RamNathKovind the President of India of #ModiGovt: #RogueIAS of #ModiGovt be Publicly Hanged at the Entrance of Supreme Court of India for Crime of Misuse of Positional Power to Overnight Transfer the Chief Secretary to Govt of West Bengal. I am Babubhai Vaghela from Ahmedabad on Signal and Whatsapp Number 9409475783. Thanks.$ 1 message Babubhai Vaghela <[email protected]> Mon, 31 May 2021 at 4:06 pm To: Prez <presidentofi[email protected]> Cc: BDVY <[email protected]>, IAS Rajiv Gauba <[email protected]>, [email protected], RajivGauba CS to GOI <[email protected]>, Kumar Arun India Heritage USA <[email protected]>, arunaroy <[email protected]>, GHAA1 Yatin Oza <[email protected]>, Prashant Bhushan <[email protected]>, Tushar Mehta <[email protected]>, [email protected], krishnkant unadkat <[email protected]>, KKNiralaIAS <[email protected]>, KKVenu Madan Prasad Clerk <[email protected]>, Jitendra Singh MoS PMO <[email protected]>, PRO Pranav Patel <pro-collector- [email protected]>, PMF <kirjaamo@vnk.fi>, PMCanada Justin Trudeau <[email protected]>, PMN <[email protected]>, PMAustralia <[email protected]>, PMD <[email protected]>, PMCanada <[email protected]>, AMMF <[email protected]>, Mukesh Ambani <[email protected]>, Mamlatdar Vejlpur <[email protected]>, Nita Ambani <[email protected]>, Mamlatdar Lakhtar VB Patel <[email protected]>, RIL Paresh Davey Vraj 9099002828 <[email protected]>, so-d- [email protected], Vejalpur BJP MLA Kishor Chauhan 9879605844 <[email protected]>, -

India's 2019 National Election and Implications for U.S. Interests

India’s 2019 National Election and Implications for U.S. Interests June 28, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45807 SUMMARY R45807 India’s 2019 National Election and Implications June 28, 2019 for U.S. Interests K. Alan Kronstadt India, a federal republic and the world’s most populous democracy, held elections to seat a new Specialist in South Asian lower house of parliament in April and May of 2019. Estimates suggest that more than two-thirds Affairs of the country’s nearly 900 million eligible voters participated. The 545-seat Lok Sabha (People’s House) is seated every five years, and the results saw a return to power of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who was chief minister of the west Indian state of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014. Modi’s party won decisively—it now holds 56% of Lok Sabha seats and Modi became the first Indian leader to win consecutive majorities since Indira Gandhi in 1971. The United States and India have been pursuing an expansive strategic partnership since 2005. The Trump Administration and many in the U.S. Congress welcomed Modi’s return to power for another five-year term. Successive U.S. Presidents have deemed India’s growing power and influence a boon to U.S. interests in Asia and globally, not least in the context of balancing against China’s increasing assertiveness. India is often called a preeminent actor in the Trump Administration’s strategy for a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” Yet there are potential stumbling blocks to continued development of the partnership. -

Kerala's Tryst

n Kerala’s Tryst with COVID 19 Psycho social support APP to combat fake news “Break The Chain” Campaign Batting and prepping for foreign arrivals Patient Rout Map Plan C- Preparing for Stage 3 Quarantine Comfort Enhanced internet connectivity Resource Management Mid-day meal delivery Officials Field visits Awareness among migrant workers Screening Sanitizer Production COVID Control Teams Use of Robot Contact Tracing Food Security and Nutrition IEC Materials Social Distancing Checking rail and road entry points Mask production by women SHGs Batting and prepping for foreign arrivals Volunteers for Help Daily Press Conferences 1 | Kerala’s Tryst with COVID 19 Kerala’s Tryst with COVID 19 Co ntents Role of KSDMA Role of Health Department Screening Contact Tracing Hospital Based and Home-Based Quarantine Working with the LSGIS/ Kudumbasree/ Jails/ CBOs For Better Resource Management Social Distancing Educational Institutions Food Security and Nutrition Plan C- Preparing for Stage 3 State Level Corona Virus Control Teams Up Information Sharing Break The Chain Campaign Screening, Mask Utilization Use of Robot Route Maps Quarantine Comfort Psycho-Social Support / Focus on Mental Health Visits from Govt Officials Daily Press Conferences Increasing Internet Connectivity Sanitiser Production App to Combat Fake News Mid-Day Meal Delivery Checking Rail and Road Entry Points Awareness Among Migrant Workers Enlisting Volunteers for Help Batting and Prepping for Foreign Arrivals 2 | Kerala’s Tryst with COVID 19 t is, perhaps, rightly said that every reports of the infection in China started disaster is an opportunity. This has been coming in. The initial area of concern was the I proved apt for Kerala, backed by the safe return of the medical students from experience of two successful battles with the Kerala, studying from Wuhan and the Nipah Virus, in its current tryst with the delegates returning from official visits to globally feared Corona Virus or the COVID-19. -

Impleadment Application

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELATE JURISDICTION I A. NO. __ OF 2020 IN W.P. (C) No.956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: OPINDIA & ORS. ….. APPLICANTS/ INTERVENORS WITH I.A.No. of 2020 AN APPLICATION FOR INTERVENTION/ IMPLEADMENT [FOR INDEX PLEASE SEE INSIDE] ADVOCATE FOR THE APPLICANT: SUVIDUTT M.S. FILED ON: 21.09.2020 INDEX S.NO PARTICULARS PAGES 1. Application for Intervention/ 1 — 21 Impleadment with Affidavit 2. Application for Exemption from filing 22 – 24 Notarized Affidavit with Affidavit 3. ANNEXURE – A 1 25 – 26 A true copy of the order of this Hon’ble Court in W.P. (C) No.956/ 2020 dated 18.09.2020 4. ANNEXURE – A 2 27 – 76 A true copy the Report titled “A Study on Contemporary Standards in Religious Reporting by Mass Media” 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION I.A. No. OF 2020 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) No. 956 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: FIROZ IQBAL KHAN ……. PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. …….. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1. OPINDIA THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, C/O AADHYAASI MEDIA & CONTENT SERVICES PVT LTD, DA 16, SFS FLATS, SHALIMAR BAGH, NEW DELHI – 110088 DELHI ….. APPLICANT NO.1 2. INDIC COLLECTIVE TRUST, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, 2 5E, BHARAT GANGA APARTMENTS, MAHALAKSHMI NAGAR, 4TH CROSS STREET, ADAMBAKKAM, CHENNAI – 600 088 TAMIL NADU ….. APPLICANT NO.2 3. UPWORD FOUNDATION, THROUGH ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY, L-97/98, GROUND FLOOR, LAJPAT NAGAR-II, NEW DELHI- 110024 DELHI …. -

Sand Mafias in India – Disorganized Crime in a Growing Economy Introduction

SAND MAFIAS IN INDIA Disorganized crime in a growing economy Prem Mahadevan July 2019 SAND MAFIAS IN INDIA Disorganized crime in a growing economy Prem Mahadevan July 2019 Cover photo: Adobe Stock – Alex Green. © 2019 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 What are the ‘sand mafias’? ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Sand: A diminishing resource .................................................................................................................................. 7 How the illicit trade in sand operates ............................................................................................................ 9 Political complicity in India’s illicit sand industry ....................................................................................11 Dividing communities from within .................................................................................................................13 -

Democracy in the Balance

DEMOCRACY IN THE BALANCE August 13, 2020 at 4:00pm Hawaii Speaker Biographies Khaldoun BARGHOUTI Israeli Affairs Editor, Alhayat Aljadida, Ramallah, Palestine @KHBarghouti Khaldoun Barghouti is a Palestinian journalist and Israeli affairs editor for the Alhayat Aljadida newspaper in Ramallah. He also hosts a daily radio program on Ajyal Radio Network where he reviews Israeli news. In addition, Mr. Barghouti contributes analysis of Israeli events and news to a quarterly research publication for the P.L.O. Research Center. He will soon join The Palestinian Forum for Israeli Studies as a permanent writer. Mr. Barghouti previously worked as a project coordinator at Birzeit University Media Development Center and was named a fellow of the East-West Center Senior Journalists Seminar in 2014. He holds a master’s in Israeli studies from Al-Quds University and a bachelor’s in journalism from Birzeit University. Lillian CUNNINGHAM Creator and Host “Presidential” and “Constitutional” podcasts, The Washington Post, Washington, DC, USA @lily_cunningham Lillian Cunningham is a journalist with The Washington Post, focusing on American politics and history. She is the creator and host of three of The Post’s most popular podcasts: “Presidential,” “Constitutional” and “Moonrise.” “Presidential” explored the past leadership and current legacy of each American president, through interviews, reporting and research into their administrations. Previously a feature writer for and editor of The Washington Post's On Leadership section, Ms. Cunningham received two Emmy Awards for her interviews with leaders in politics, business and the arts. Additionally, she is a Webby Award honoree, an Academy of Podcasters finalist, and a former Jefferson Fellow with the East-West Center. -

Reel to Realpolitik: the Golden Years of Indian Cinema Overseas

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 10 Issue 5 Ser. II || May 2021 || PP 09-16 Reel To Realpolitik: The Golden Years Of Indian Cinema Overseas Saumya Singh School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India ABSTRACT This paper seeks to establish the links between cinema and foreign policy of a state. An important illustration is the popular reception of Bollywood abroad in the heydays of cold war. In a world simmering with tensions, the nascent film industry of India reflected the crisis of existence that its newly independent state faced. The imagination of India seeped into the consciousness of the country’s artistic, cultural, political and social scene. Bollywood had produced the best movies like Awaara and Mother India with stars such as Raj Kapoor and Nargis winning the hearts of Turkish, Russians and Nigerians alike. The aim here is to connect the acceptance of Indian cinema in the corners of the world during the 1950s and 1960s as a success of the idea of third world. Now, in a multipolar order, when India seeks to acquire a global ascendancy, it can judiciously conceive it's hard and soft power resources to woo the world. Taking cue from history, we propose a cautious utilisation of cultural resources for foreign policy ends. KEYWORDS- soft power, diplomacy, foreign policy, Bollywood, Indian Culture --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 08-05-2021 Date of Acceptance: 22-05-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION The aim of this paper is to study how Bollywood functioned as a tool of promoting India’s soft power interests in the decade of 1950’s and 1960’s. -

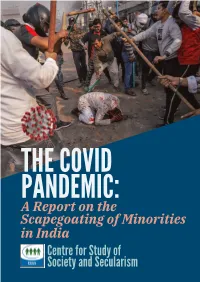

THE COVID PANDEMIC: a Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism I

THE COVID PANDEMIC: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism i The Covid Pandemic: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism Mumbai ii Published and circulated as a digital copy in April 2021 © Centre for Study of Society and Secularism All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including, printing, photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher and without prominently acknowledging the publisher. Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, 603, New Silver Star, Prabhat Colony Road, Santacruz (East), Mumbai, India Tel: +91 9987853173 Email: [email protected] Website: www.csss-isla.com Cover Photo Credits: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters iii Preface Covid -19 pandemic shook the entire world, particularly from the last week of March 2020. The pandemic nearly brought the world to a standstill. Those of us who lived during the pandemic witnessed unknown times. The fear of getting infected of a very contagious disease that could even cause death was writ large on people’s faces. People were confined to their homes. They stepped out only when absolutely necessary, e.g. to buy provisions or to access medical services; or if they were serving in essential services like hospitals, security and police, etc. Economic activities were down to minimum. Means of public transportation were halted, all educational institutions, industries and work establishments were closed. -

Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India (P Ilbu Sh Tniojde Llyy Iw Tthh I

REUTERS INSTITUTE for the STUDY of SELECTED RISJ PUBLICCATIONSATIONSS REPORT JOURNALISM Abdalla Hassan Raymond Kuhn and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (eds) Media, Reevvolution, and Politics in Egyyppt: The Story of an Po lacitil Journalism in Transition: Western Europe in a Uprising Comparative Perspective (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri (published tnioj llyy htiw I.B.Tau s)ri Robert G. Picard (ed.) Nigel Bowles, James T. Hamilton, David A. L. Levvyy )sde( The Euro Crisis in the Media: Journalistic Coverage of Transparenccyy in Politics and the Media: Accountability and Economic Crisis and European Institutions Open Government (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tauris) (published tnioj llyy htiw I.B.Tau s)ri Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (ed.) Julian Pettl ye (e ).d Loc Jla naour lism: The Decli ofne News pepa rs and the Media and Public Shaming: Drawing the Boundaries of Rise of Digital Media Di usolcs re Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri (publ(publ si heed joi tn llyy tiw h II.. T.B aur )si Wendy N. Wy de(tta .) La ar Fi le dden The Ethics of Journalism: Individual, stIn itutional and Regulating ffoor Trust in Journalism: Standards Regulation Cu nIlarutl fflluences in the Age of Blended Media (published jointllyy iw tthh I.B.Tau s)ri Arijit Sen and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen David A. L eL. vvyy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (eds) The Changing Business of Journalism and its Implications for Demo arc ccyy May 2016 CHALLENGES Robert G. Picard and Hannah Storm Nick Fras re The Kidnapping of Journalists: Reporting