Recovery Plans for Brown Bear Conservation in the Cantabrian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

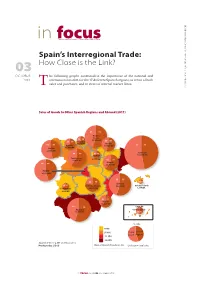

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

Oviedo Point 1000 W MITCHELL HAMMOCK ROAD, OVIEDO, FL 32765

FOR LEASE > RETAIL > NEW DEVELOPMENT Oviedo Point 1000 W MITCHELL HAMMOCK ROAD, OVIEDO, FL 32765 Highlights Oviedo Point is a new retail/restaurant development. Outparcels and potential retail > Join Wawa, Orangetheory Fitness, Moe’s, Mission BBQ, space for lease. 1000 Degrees Pizza and CareSpot Location > 1.83 acre outparcel available for ground lease, BTS, for sale, or can be developed as a multi-tenant building with drive-thru > 1.1-1.5 acre pad available for sale - ideal for daycare user > Generous parking ratio of 6/1,000 SF > 0.3 miles to Oviedo Medical Center, opening early 2017, which will have 200+ employees & 86 beds > Great access with signage opportunity on Mitchell Hammock Road > Strong growth with new retail, residential and medical developments underway, draw significant traffic to trade area GENNY HALL CHRISTIN JONES DAVID GABBAI COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL Director, Retail Services Director, Retail Services Managing Director, Retail Services 255 South Orange Avenue, Suite 1300 +1 407 362 6162 +1 407 362 6138 +1 407 362 6123 Orlando, FL 32801 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.colliers.com/centralflorida Outparcel Conceptual Layout Multi-tenant Building Conceptual Layout 42,000 AADT 42,000 AADT Mitchell Hammock Road Mitchell Hammock Road 85’ 75’ • 1.1-1.5 AC For Sale • 1.1-1.5 AC For Sale • 1.83 acres • 6,375 SF multi-tenant retail • Ground Lease, BTS, For Sale building for lease • 100 parks + cross parking • Graded pad delivery Availability Availability Suite Status Size (SF) -

The Beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia * Dimas Martín-Socas a, , María Dolores Camalich Massieu a, Jose Luis Caro Herrero b, F. Javier Rodríguez-Santos c a U.D.I. de Prehistoria, Arqueología e Historia Antigua (Dpto. Geografía e Historia), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus Guajara, 38071 Tenerife, Spain b Dpto. Lenguajes y Ciencias de la Computacion, Universidad de Malaga, Complejo Tecnologico, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain c Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistoricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria. Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. Los Castros, 52. 39005 Santander, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Early Neolithic in Andalusia shows great complexity in the implantation of the new socioeconomic Received 31 January 2017 structures. Both the wide geophysical diversity of this territory and the nature of the empirical evidence Received in revised form available hinder providing a general overview of when and how the Mesolithic substrate populations 6 June 2017 influenced this process of transformation, and exactly what role they played. The absolute datings Accepted 22 June 2017 available and the studies on the archaeological materials are evaluated, so as to understand the diversity Available online xxx of the different zones undergoing the neolithisation process on a regional scale. The results indicate that its development, initiated in the middle of the 6th millennium BC and consolidated between 5500 and Keywords: Iberian Peninsula 4700 cal. BC, is parallel and related to the same changes documented in North Africa and the different Andalusia areas of the Central-Western Mediterranean. -

Cantabria Y Asturias Seniors 2016·17

Cantabria y Asturias Seniors 2016·17 7 días / 6 noches Hotel Zabala 3* (Santillana del Mar) € Hotel Norte 3* (Gijón) desde 399 Salida: 11 de junio Precio por persona en habitación doble Suplemento Hab. individual: 150€ ¡TODO INCLUIDO! 13 comidas + agua/vino + excursiones + entradas + guías ¿Por qué reservar este viaje? ¿Quiere conocer Cantabria y Asturias? En nuestro circuito Reserve por sólo combinamos lo mejor de estas dos comunidades para que durante 7 días / 6 noches conozcas a fondo los mejores rincones de la geografía. 50 € Itinerario: Incluimos: DÍA 1º. BARCELONA – CANTABRIA • Asistencia por personal de Viajes Tejedor en el punto de salida. Salida desde Barcelona. Breves paradas en ruta (almuerzo en restaurante incluido). • Autocar y guía desde Barcelona y durante todo el recorrido. Llegada al hotel en Cantabria. Cena y alojamiento. • 3 noches de alojamiento en el hotel Zabala 3* de Santillana del Mar y 2 noches en el hotel Norte 3* de Gijón. DÍA 2º. VISITA DE SANTILLANA DEL MAR y COMILLAS – VISITA DE • 13 comidas con agua/vino incluido, según itinerario. SANTANDER • Almuerzos en ruta a la ida y regreso. Desayuno. Seguidamente nos dirigiremos a la localidad de Santilla del Mar. Histórica • Visitas a: Santillana del Mar, Comillas, Santander, Santoña, Picos de Europa, Potes, población de gran belleza, donde destaca la Colegiata románica del S.XII, declarada Oviedo, Villaviciosa, Lastres, Tazones, Avilés, Luarca y Cudillero. Monumento Nacional. Las calles empedradas y las casas blasonadas, configuran un paisaje • Pasaje de barco de Santander a Somo. urbano de extraordinaria belleza. Continuaremos viaje a la cercana localidad de Comillas, • Guías locales en: Santander, Oviedo y Avilés. -

Brown Bear Conservation Action Plan for Europe

Chapter 6 Brown Bear Conservation Action Plan for Europe IUCN Category: Lower Risk, least concern CITES Listing: Appendix II Scientific Name: Ursus arctos Common Name: brown bear Figure 6.1. General brown bear (Ursus arctos) distribution in Europe. European Brown Bear Action Plan (Swenson, J., et al., 1998). 250 km ICELAND 250 miles Original distribution Current distribution SWEDEN FINLAND NORWAY ESTONIA RUSSIA LATVIA DENMARK IRELAND LITHUANIA UK BELARUS NETH. GERMANY POLAND BELGIUM UKRAINE LUX. CZECH SLOVAKIA MOLDOVA FRANCE AUSTRIA SWITZERLAND HUNGARY SLOVENIA CROATIA ROMANIA BOSNIA HERZ. THE YUGOSL. FEDER. ANDORRA BULGARIA PORTUGAL ITALY MACEDONIA SPAIN ALBANIA TURKEY GREECE CYPRUS 55 Introduction assumed to live in southwestern Carinthia, representing an outpost of the southern Slovenian population expanding In Europe the brown bear (Ursus arctos) once occupied into the border area with Austria and Italy (Gutleb 1993a most of the continent including Scandinavia, but since and b). The second population is located in the Limestone about 1850 has been restricted to a more reduced range Alps of Styria and Lower Austria and comprises 8–10 (Servheen 1990), see Figure 6.1. individuals; it is the result of a reintroduction project started by WWF-Austria in 1989. In addition to these populations, the Alps of Styria and Carinthia and to a lesser Status and management of the extent also of Salzburg and Upper Austria, are visited by brown bear in Austria migrating individuals with increasing frequency. A third Georg Rauer center of bear distribution is emerging in northwestern Styria and the bordering areas of Upper Austria (Dachstein, Distribution and current status Totes Gebirge, and Sengsengebirge) where, since 1990, 1–3 bears have been present almost continuously (Frei, J., At present, there are just a few brown bears living in Bodner, M., Sorger, H.P. -

Comparitive Study of the Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin

III CONGRESSO INTERNAZIONALE DI STUDI SULLA SINDONE TURIN, 5TH TO 7TH JUNE 1998 COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE SUDARIUM OF OVIEDO AND THE SHROUD OF TURIN By; Guillermo Heras Moreno, Civil Engineer, Head of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). José-Delfín Villalaín Blanco, DM, PhD. Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Valencia, Spain. Vice-President of the Investigation. Spanish Centre for Sindonology (CES). Member of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). Jorge-Manuel Rodríguez Almenar, Professor at the University of Valencia, Spain. Vice-President of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (CES). Vicecoordinator of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). Drawings by: Margarita Ordeig Corsini, Catedrático de Dibujo, and Enrique Rubio Cobos. Spanish Centre for Sindonology (CES). Translated from the Spanish by; Mark Guscin, BA M Phil in Medieval Latin. Member of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). Revised by; Guillermo Heras Moreno CENTRO ESPAÑOL DE SINDONOLOGÌA. AVDA. REINO DE VALENCIA, 53. 9-16™ • E-46005-VALENCIA. Telèfono-Fax: 96- 33 459 47 • E-Mail: [email protected] ©1998 All Rights Reserved Reprinted by Permission 1 1 - INTRODUCTION. Since Monsignor Giulio Ricci first strongly suggested in 1985 that the cloth venerated in Oviedo (Asturias, Northern Spain), known as the Sudarium of Oviedo, and the Shroud of Turin had really been used on the same corpse, the separate study of each cloth has advanced greatly, according to the terminology with which scientific method can approach this hypothesis in this day and age. The paper called "The Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin, two complementary Relics?" was read at the Cagliari Congress on Dating the Shroud in 1990. -

The North Way

PORTADAS en INGLES.qxp:30X21 26/08/09 12:51 Página 6 The North Way The Pilgrims’ Ways to Santiago in Galicia NORTE EN INGLES 2009•.qxd:Maquetación 1 25/08/09 16:19 Página 2 NORTE EN INGLES 2009•.qxd:Maquetación 1 25/08/09 16:20 Página 3 The North Way The origins of the pilgrimage way to Santiago which runs along the northern coasts of Galicia and Asturias date back to the period immediately following the discovery of the tomb of the Apostle Saint James the Greater around 820. The routes from the old Kingdom of Asturias were the first to take the pilgrims to Santiago. The coastal route was as busy as the other, older pilgrims’ ways long before the Spanish monarchs proclaimed the French Way to be the ideal route, and provided a link for the Christian kingdoms in the North of the Iberian Peninsula. This endorsement of the French Way did not, however, bring about the decline of the Asturian and Galician pilgrimage routes, as the stretch of the route from León to Oviedo enjoyed even greater popularity from the late 11th century onwards. The Northern Route is not a local coastal road for the sole use of the Asturians living along the Alfonso II the Chaste. shoreline. This medieval route gave rise to an Liber Testamenctorum (s. XII). internationally renowned current, directing Oviedo Cathedral archives pilgrims towards the sanctuaries of Oviedo and Santiago de Compostela, perhaps not as well- travelled as the the French Way, but certainly bustling with activity until the 18th century. -

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. the Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. The Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia Arturo de Lombera Hermida and Ramón Fábregas Valcarce (eds.) Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011, 143 pp. (paperback), £29.00. ISBN-13: 97891407308609. Reviewed by JOÃO CASCALHEIRA DNAP—Núcleo de Arqueologia e Paleoecologia, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve, Campus Gambelas, 8005- 138 Faro, PORTUGAL; [email protected] ompared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, Galicia investigation, stressing the important role of investigators C(NW Iberia) has always been one of the most indigent such as H. Obermaier and K. Butzer, and ending with a regions regarding Paleolithic research, contrasting pro- brief presentation of the projects that are currently taking nouncedly with the neighboring Cantabrian rim where a place, their goals, and auspiciousness. high number of very relevant Paleolithic key sequences are Chapter 2 is a contribution of Pérez Alberti that, from known and have been excavated for some time. a geomorphological perspective, presents a very broad Up- This discrepancy has been explained, over time, by the per Pleistocene paleoenvironmental evolution of Galicia. unfavorable geological conditions (e.g., highly acidic soils, The first half of the paper is constructed almost like a meth- little extension of karstic formations) of the Galician ter- odological textbook that through the definition of several ritory for the preservation of Paleolithic sites, and by the concepts and their applicability to the Galician landscape late institutionalization of the archaeological studies in supports the interpretations outlined for the regional inter- the region, resulting in an unsystematic research history. land and coastal sedimentary sequences. As a conclusion, This scenario seems, however, to have been dramatically at least three stadial phases were identified in the deposits, changed in the course of the last decade. -

Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Chapter 24. THE BAY OF BISCAY: THE ENCOUNTERING OF THE OCEAN AND THE SHELF (18b,E) ALICIA LAVIN, LUIS VALDES, FRANCISCO SANCHEZ, PABLO ABAUNZA Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) ANDRE FOREST, JEAN BOUCHER, PASCAL LAZURE, ANNE-MARIE JEGOU Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la MER (IFREMER) Contents 1. Introduction 2. Geography of the Bay of Biscay 3. Hydrography 4. Biology of the Pelagic Ecosystem 5. Biology of Fishes and Main Fisheries 6. Changes and risks to the Bay of Biscay Marine Ecosystem 7. Concluding remarks Bibliography 1. Introduction The Bay of Biscay is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, indenting the coast of W Europe from NW France (Offshore of Brittany) to NW Spain (Galicia). Tradition- ally the southern limit is considered to be Cape Ortegal in NW Spain, but in this contribution we follow the criterion of other authors (i.e. Sánchez and Olaso, 2004) that extends the southern limit up to Cape Finisterre, at 43∞ N latitude, in order to get a more consistent analysis of oceanographic, geomorphological and biological characteristics observed in the bay. The Bay of Biscay forms a fairly regular curve, broken on the French coast by the estuaries of the rivers (i.e. Loire and Gironde). The southeastern shore is straight and sandy whereas the Spanish coast is rugged and its northwest part is characterized by many large V-shaped coastal inlets (rias) (Evans and Prego, 2003). The area has been identified as a unit since Roman times, when it was called Sinus Aquitanicus, Sinus Cantabricus or Cantaber Oceanus. The coast has been inhabited since prehistoric times and nowadays the region supports an important population (Valdés and Lavín, 2002) with various noteworthy commercial and fishing ports (i.e. -

Working Papers in Economic History the Roots of Land Inequality in Spain

The roots of land inequality in Spain Francisco J. Beltrán Tapia, Alfonso Díez-Minguela, Julio Martinez-Galarraga, Daniel A. Tirado-Fabregat (Universitat de València) Working Papers in Economic History 2021-01 ISSN: 2341-2542 Serie disponible en http://hdl.handle.net/10016/19600 Web: http://portal.uc3m.es/portal/page/portal/instituto_figuerola Correo electrónico: [email protected] Creative Commons Reconocimiento- NoComercial- SinObraDerivada 3.0 España (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 ES) The roots of land inequality in Spain Francisco J. Beltrán Tapia (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU) Alfonso Díez-Minguela (Universitat de València) Julio Martinez-Galarraga (Universitat de València) Daniel A. Tirado-Fabregat (Universitat de València) Abstract There is a high degree of inequality in land access across Spain. In the South, and in contrast to other areas of the Iberian Peninsula, economic and political power there has traditionally been highly concentrated in the hands of large landowners. Indeed, an unequal land ownership structure has been linked to social conflict, the presence of revolutionary ideas and a desire for agrarian reform. But what are the origins of such inequality? In this paper we quantitatively examine whether geography and/or history can explain the regional differences in land access in Spain. While marked regional differences in climate, topography and location would have determined farm size, the timing of the Reconquest, the expansion of the Christian kingdoms across the Iberian Peninsula between the 9th and the 15th centuries at the expense of the Moors, influenced the type of institutions that were set up in each region and, in turn, the way land was appropriated and distributed among the Christian settlers. -

Tesis Doctoral-OVIEDO Guillermo Ruben

TESIS DOCTORAL Valoración funcional y niveles de actividad física en personas con discapacidad intelectual ; efectos de un programa de actividad física aeróbico, de fuerza y equilibrio Guillermo Ruben Oviedo 2014 Directora: Dra. Miriam Guerra Balic TESIS DOCTORAL 472 (28-02-90) 472 Título: Valoración funcional y niveles de actividad física en personas con discapacidad intelectual; efectos de un programa de actividad física aeróbico, de fuerza y equilibrio Privada. Rgtre. Fund. Generalitat de Catalunya núm. Catalunya de Fund. Generalitat Privada. Rgtre. Realizada por Guillermo Ruben Oviedo En el Centro Facultad de Psicología, Ciencias de la Educación y del Deporte Blanquerna. Universidad Ramon Llull y en el Departamento de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del C.I.F. G: 59069740 Universitat Ramon Lull Fundació Lull Fundació Ramon Universitat C.I.F.59069740 G: Deporte Dirigida por Dra. Miriam Guerra Balic C. Claravall, 1-3 08022 Barcelona Tel. 936 022 200 Fax 936 022 249 E-mail: [email protected] www.url.es DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SPORT SCIENCES FPCEE BLANQUERNA UNIVERSITAT RAMON LLULL FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY LEVELS IN PEOPLE WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILIT Y; EFFECT OF AN AEROBIC, STRE NGTH AND BALANCE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL PhD Thesis presented by: Guillermo Ruben Oviedo To obtain the degree of PhD by the FPCEE Blanquerna, Universitat Ramon Llull Supervised by: Dr. Miriam Guerra Balic Barcelona 2014 Este trabajo ha estado posible gracias a la ayuda recibida para la contratación y formación de Personal Investigador Joven (FI) concedida por la Agencia de Gestión de Ayudas Universitarias y de Investigación (AGAUR) de la secretaría de Universidades e Investigación (SUR) del Departamento de Economía y Conocimiento (ECO) de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2013FI_B2 00091) y por el Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de España (I+D+i Ref: DEP2012-35335). -

33 the Radiocarbon Chronology of El Mirón Cave

RADIOCARBON, Vol 52, Nr 1, 2010, p 33–39 © 2010 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona THE RADIOCARBON CHRONOLOGY OF EL MIRÓN CAVE (CANTABRIA, SPAIN): NEW DATES FOR THE INITIAL MAGDALENIAN OCCUPATIONS Lawrence Guy Straus1,2 • Manuel R González Morales2 ABSTRACT. Three additional radiocarbon assays were run on samples from 3 levels lying below the classic (±15,500 BP) Lower Cantabrian Magdalenian horizon in the outer vestibule excavation area of El Mirón Cave in the Cantabrian Cordillera of northern Spain. Although the central tendencies of the new dates are out of stratigraphic order, they are consonant with the post-Solutrean, Initial Magdalenian period both in El Mirón and in the Cantabrian region, indicating a technological transition in preferred weaponry from foliate and shouldered points to microliths and antler sagaies between about 17,000–16,000 BP (uncalibrated), during the early part of the Oldest Dryas pollen zone. Now with 65 14C dates, El Mirón is one of the most thor- oughly dated prehistoric sites in western Europe. The until-now poorly dated, but very distinctive Initial Cantabrian Magdale- nian lithic artifact assemblages are briefly summarized. INTRODUCTION El Mirón Cave is located in the upper valley of the Asón River in eastern Cantabria Province in northern Spain, about 100 m up from the valley floor on the steep western face of a mountain in the second foothill range of the Cantabrian Cordillera, about halfway between the cities of Santander and Bilbao. The site location in the town of Ramales de la Victoria (431448N, 3275W) is 260 m above present sea level, and about 20 km from the present shore of the Bay of Biscay (and about 25–30 km from the Tardiglacial shore).