Yondorf Block and Hall 758 W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Comment Summary Report

City of Chicago DRAFT Equitable Transit- Oriented Development (eTOD) Policy Plan Public Comment Summary Report 1 Contents Summary of Public Comments & Outreach Efforts ...................................................................................... 3 Themes from Public Comments .................................................................................................................... 4 Themes from Community Conversations ..................................................................................................... 5 Individual Comments .................................................................................................................................... 5 See Appendix for Attached Letters submmitted as public comment 2 Summary of Public Comments & Outreach Efforts The following document summarizes the public comments on the City of Chicago’s proposed ETOD Policy Plan, received between September 14 and October 29, 2020. Overview of comments submitted through email: 59 total public comments 24 comments from organizations 35 comments from individuals Local Groups Developers Transportation Environmental Chicago Metropolitan 3e. Studio LLC Metra Environmental Law & Policy Agency for Planning Center Esperanza Health Centers The Community Builders Pace Bus Illinois Environmental Council Metropolitan Planning Hispanic Housing RTA Sustainable Englewood Council Development Coordination Initiatives Red Line Extension Coalition Urban Land Institute Zipcar Elevate Energy Roseland Heights Share Mobility Community -

CDOT (312) 744-0707 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 5, 2014 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] Pete Scales, CDOT (312) 744-0707 [email protected] MAYOR EMANUEL ANNOUNCES CITY REACHES HALFWAY POINT OF 100-MILE GOAL FOR PROTECTED BIKE LANES BY 2015 Next 20 Miles Installed This Spring; 30 More Miles in Design Phase Mayor Rahm Emanuel today announced the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT) is halfway finished with the plan to install 100 miles of protected bike lanes by 2015, and is on track to achieve that milestone by early next year. “Improving our bicycling facilities is critical to creating the quality of life in Chicago that attracts businesses and families to the city,” Mayor Emanuel said. “We are making Chicago the most bike-friendly city in the United States.” Twenty more miles of protected bike lanes will be installed this spring and summer, with the remaining 30 miles in design phase and planned for installation later this year and early 2015. In 2013, CDOT installed 31 miles of new or restriped facilities, including 19 miles of protected bike lanes, bringing the number of protected bike lanes installed in Chicago since Mayor Emanuel came into office in May 2011 to 49 miles. Chicago’s bikeways now total more than 207 miles, according to CDOT’s report, 2013 Bikeways – Year In Review, which was released today. “Chicago is a national leader in building new and improved cycling facilities and setting a new standard for other cities to follow,” said CDOT Commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld. “We are looking forward to continuing our bikeways construction efforts this summer to make Chicago the best cycling city in America.” Bikeways achievements in 2013 include: • Chicago’s first Neighborhood Greenway on Berteau Avenue • Bicycle-friendly treatments on three bridges • Installation of 12 bike corrals • 35,000 cyclists counted in monthly biking data collection events • Installation of 300 Divvy bike-share stations In addition to installing new lanes, maintenance of existing facilities continued as well. -

Illinoistollwaymap-June2005.Pdf

B C D E F G H I J K L Issued 2005 INDEX LEE ST. 12 45 31 Racine DESPLAINES RIVER RD. Janesville 43 75 Sturtevant 294 Addison . .J-6 Grayslake . .I-3 Palos Hills . .J-8 Union Grove Devon Ave 11 Burlington 90 Plaza Alden . .G-2 Gurnee . .J-3 Palos Park . .J-8 Footville Elmwood Park 11 Algonquin . .H-4 Hammond . .L-8 Park City . .J-3 Elkhorn 11 Alsip . .K-8 Hanover Park . .I-6 Park Forest . .K-9 NORTHWEST 51 11 72 Amboy . .C-7 Harmon . .B-7 Park Ridge . .K-5 14 11 TOLLWAY Antioch . .I-2 Harvey . .K-8 Paw Paw . .E-8 94 142 32 1 Arlington . .C-9 Harwood Heights . .K-6 Phoenix . .L-8 39 11 Delavan 36 HIGGINS RD. 1 Arlington Heights . .J-5 Hawthorn Woods . .I-4 Pingree Grove . .H-5 90 41 31 TRI-STATE TOLLWAY Ashton . .C-6 Hebron . .H-2 Plainfield . .H-8 83 67 142 Aurora . .H-7 Hickory Hills . .K-7 Pleasant Prairie . .J-2 50 O’Hare East Barrington . .I-5 Highland . .L-9 Poplar Grove . .E-3 Plaza 72 Bartlett . .I-6 Highland Park . .K-4 Posen . .K-8 Darien 75 45 90 Batavia . .H-6 Hillcrest . .D-6 Prospect Heights . .J-5 Beach Park . .K-3 Hillside . .J-6 Richton Park . .K-9 50 158 River Rd. Bedford Park . .K-7 Hinkley . .F-7 Racine . .K-1 50 Plaza Paddock Lake Bellwood . .J-6 Hinsdale . .J-7 Richmond . .H-2 213 Lake Geneva O’Hare West KENNEDY EXPY. 43 14 Williams Bay Kenosha Plaza Beloit . -

95Th Street Project Definition

Project Definition TECHNICAL MEMORANUM th 95 Street Line May 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary...............................................................................................ES-1 Defining the Project......................................................................................ES-2 Project Features and Characteristics ..........................................................ES-3 Next Steps .....................................................................................................ES-7 1 Introduction .........................................................................................................1 1.1 Defining the Project ...............................................................................2 1.2 95th Street Line Project Goals.................................................................2 1.3 Organization of this Plan Document.....................................................3 2 Corridor Context ..................................................................................................6 2.1 Corridor Route Description ....................................................................6 2.2 Land Use Character ..............................................................................6 2.3 Existing & Planned Transit Service .........................................................8 2.4 Local and Regional Plans......................................................................8 2.5 Historical Resources ...............................................................................9 -

Licensed Contractor Report

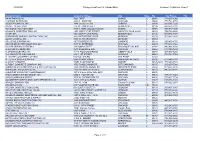

3/23/2020 Chicago Department of Transportation Licensed_Contractors_Report Company Name Company Address City State Zip Day Phone Fax AA ANTHONYS INC 9621 TRIPP SKOKIE IL 60076 (773)230-1062 A ARROW SEWERAGE 4243 N. MONITOR CHICAGO IL 60634 (773)761-0759 ABBEY PAVING CO, INC. 1949 County Line Rd AURORA IL 60504 (630)585-7220 ABBOTT INDUSTRIES 225 WILLIAM STREET BENSENVILLE IL 60106 (630)595-2320 ACE CONSTRUCTION CORP 7334 N. MONTICELLO AVENUE SKOKIE IL 60076 (847)679-4155 ACHILLES CONSTRUCTION, INC. 4857 WEST 171ST STREET COUNTRY CLUB HILLS IL 60478 (708)799-0525 ACURA INC 556 COUNTY LINE ROAD BENSENVILLE IL 60106 (630)766-9979 ADAMSON PLUMBING CONTRACTORS, INC. 860 SOUTH FIENE DRIVE ADDISON IL 60101 (312)492-7600 ADEN PLUMBING INC 3804 W PRETSWICK ST MCHENRY IL 60050 ADJUSTABLE FORMS INC 1 E PROGRESS RD LOMBARD IL 60148 (630)953-8700 ADVANCED WATER SOLUTIONS LLC 7637 W. PETERSON CHICAGO IL 60631 (773)636-0066 A & H PLUMBING & HEATING 330 BOND STREET ELK GROVE VILLAGE IL 60007 (847)981-8800 ALARCON PLUMBING INC 8518 S KEDVALE AVE CHICAGO IL 60652 (773)349-1264 ALDRIDGE ELECTRIC INC 844 E. ROCKLAND ROAD LIBERTYVILLE IL 60048 (847)680-5200 ALL CONCRETE CHICAGO INC 414 E 1ST STREET HINSDALE IL 60521 (773)729-7004 ALLSTATE CONCRETE CUTTING 514 ROLLINS RD INGLESIDE IL 60041 ALL STATE SEWER & WATER 6941 W MONTROSE HARWOOD HEIGHTS IL 60706 (312)446-7300 ALMIGHTY ROOTER 16858 S LATHROP #1 HARVEY IL 60426-6031 (773)284-6616 ALRIGHT CONCRETE COMPANY INC. 1500 RAMBLEWOOD DR. STREAMWOOD IL 60107 (630)250-7088 AMERICAN BACKHOE SERVICE & EXCAVATING CO 2560 FEDERAL SIGNAL DR UNIVERSITY PARK IL 60484 (815)469-2100 AMERICAN LANDSCAPING, INC 2233 PALMER DR. -

Chicago - Urban New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20

Chicago - Urban New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20 ID PROPERTY UNITS 7 Edge on Broadway 105 7 8 Eagles Building Redevelopment 134 131 14 Four50 Residences 80 57 22 Lathrop Homes Redevelopment 414 Total Lease Up 733 111 35 1900 West Lawrence Avenue 59 45 Dakin Street & Sheridan Road 54 110 Foster Beach Total Under Construction 113 56 54 1801 West Grace Street 62 132 55 1825 West Lawrence Avenue 166 56 5356 North Sheridan Road 50 113 57 Loft Lago 59 58 Wilson Red Line Development 110 35 137 55 59 Lake Shore Drive 332 Mixed-Use Development 112 58 Montrose Beach 60 Panorama 140 134 61 Clark and Drummond 84 133 62 Edith Spurlock 485 Redevelopment-Lincoln Park 136 109 Lathrop Chicago Redevelopment Phase II 702 110 5440 North Sheridan Road 78 111 Edgewater Medical Center Redevelopment 141 135 45 112 4601 North Broadway 197 114 8 113 Draper Phase II, The 368 54 114 3921 North Sheridan 120 59 Total Planned 3,094 141 131 Loft Lago 59 132 Park Edgewater 365 60 133 1030 West Sunnyside Avenue 144 14 134 4511 North Clark Street 56 139 Lincoln Park 135 Immaculata High School 220 138 136 Montrose Phase II, The 160 137 Winthrop Avenue Multi-Residential 84 109 140 138 Ashland Avenue 79 22 198 139 Bel Ray Redevelopment 136 62 61 Peggy Notebaert 140 Lincoln Park Plaza Phase II 57 198 Hotel Covent Redevelopment 114 Nature Museum 141 Optima Lakeview 246 Total Prospective 1,720 2000 ft Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Chicago - Urban New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20 162 30 81 -

Central Tri-State Tollway (I-294) 95Th Street to Balmoral Avenue, Mile Post 17.7 to 40.0 Corridor Improvements

Central Tri-State Tollway (I-294) 95th Street to Balmoral Avenue, Mile Post 17.7 to 40.0 Corridor Improvements Corridor Concept Study Tollway Planning Project Number: TSMP2020 Prepared for Prepared by September, 2014 VOLUME 1 REPORT th Central Tri-State Tollway (I-294) │ 95 Street to Balmoral Ave. │ Corridor Concept Study Table of Contents Volume 1 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Summary of Internal Meetings ................................................................................. 11 2.2 Summary of External Meetings ............................................................................. 13 2.3 Presentations to Tollway Staff ............................................................................... 13 3.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS .............................................................................................. 14 3.1 Project Limits ......................................................................................................... 14 3.2 Improvement History ............................................................................................. 14 3.3 Record Drawings ................................................................................................... 15 3.4 Overview of Project Area ...................................................................................... -

A Safe Haven 2750 W Roosevelt Rd Chicago, IL 60608 773.435.8386

A Safe Haven Shedd Aquarium 5 2750 W Roosevelt Rd 1 1200 S. Lake Shore Dr. Chicago, IL 60608 Chicago, IL 60605 773.435.8386 – volunteer coordinator 312.939.2438 [email protected] www.sheddaquarium.org/volunteering www.asafehaven.org Contact: Todd Maskel at A Safe Haven helps homeless people that are [email protected] in sudden or chronic social and financial crisis address the root causes of their problems and The Aquarium aims to engage, inspire we help them achieve sustainable self- entertain, and educate the public. In addition, suffiency. they promote conservation to protect the animals and their habitats. Help with public Abraham Lincoln Center Head Start 2 interpretation by interacting with museum 1354 W. 61 St. guests. Chicago, IL 60636 773.471.5100 Community Building Tutors (CBT) 6 www.abrahamlincolncentre.org 1314 S. Racine Ave Chicago, IL 60608 Contact: Rasalyn Lee one week in advance at 773.499.8715 [email protected] www.cbtutors.org After School Matters 3 Contact: Angel Diaz at [email protected] 66 E Randolph St Chicago, IL 60601 Community Building Tutors creates tutoring 312.768.5200 – volunteer contact opportunities that focuses on academic [email protected] improvement, character development, and increased community involvement. Help tutor After School Matters is a non-profit elementary students organization that offers Chicago high school teens innovative out-of-school activities Poder Learning Center 7 through Science, Sports, Tech, Words, and the 1637 S Allport nationally recognized Gallery programs. Chicago, IL 60608 312.262.2002 Adler Planetarium 4 www.poderlc.org 1300 S. Lake Shore Dr Contact: Cecilia Hernandez at Chicago, IL 60605 [email protected] 312.542.2411 http://www.adlerplanetarium.org/getinvolved/vo Poder Learning Center provides tuition-free lunteer English and technology classes to adult Contact: Maria Christus at immigrants so they can succeed. -

City of Chicago Requirements for Scooter Sharing Emerging Business Permit Pilot Program

CITY OF CHICAGO REQUIREMENTS FOR SCOOTER SHARING EMERGING BUSINESS PERMIT PILOT PROGRAM I. Definitions. For purposes of this scooter sharing emerging business permit application document, the following definitions shall apply: “Business operations window” means the time period(s) within the term of the scooter sharing EBP in which vendors are allowed to conduct business operations, i.e., offering scooter rental services in accordance with the terms of the scooter sharing EBP. “City” means the City of Chicago. “Code” means the Municipal Code of Chicago. “Commissioner” means the City’s Commissioner of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection. “Pilot Area” means the geographic area in which a vendor’s scooters may be rented from and end a trip, subject to the terms of the pilot program, and all generally applicable parking rules and restrictions. The pilot area for the pilot program shall be the entire portion of the City bounded as follows, and as shown in the attached Pilot Area Map: beginning at the intersection of North California Avenue and West Irving Park Road; thence east on West Irving Park Road to the North Branch Chicago River; thence southeasterly along the North Branch Chicago River to North Halsted Street; thence south on North Halsted Street to the South Branch of Chicago River; hence southwesterly along the South Branch of Chicago River to South Cicero Avenue; thence north on South Cicero Avenue to West Pershing Road; thence east on West Pershing Road to the Chicago Belt Railroad; thence north along the Chicago Belt Railroad to Roosevelt Road; thence west on Roosevelt Road to South Austin Boulevard; thence north on South Austin Boulevard to West North Avenue; thence west on West North Avenue to Harlem Avenue; thence north on Harlem Avenue to West Irving Park Road; hence east on West Irving Park Road to the place of the beginning. -

Chicago Downtown Chicago Connections

Stone Scott Regional Transportation 1 2 3 4 5Sheridan 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dr 270 ter ss C en 619 421 Edens Plaza 213 Division Division ne 272 Lake Authority i ood s 422 Sk 422 u D 423 LaSalle B w 423 Clark/Division e Forest y okie Rd Central 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie 422 The Regional Transportation Authority r P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware 620 421 0 E/W eehan Preserve Wilmette C Union Pacific/North Line 3rd 143 l Forest Baha’i Temple F e La Elm ollw Green Bay a D vice 4th v Green Glenview Glenview to Waukegan, Kenosha and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T i lo 210 626 Evanston Elm n (RTA) provides financial oversight, Preserve bard Linden nonstop between Michigan/Delaware e Dewes b 421 146 s Wilmette 221 Dear Milw Foster and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) funding, and regional transit planning R Glenview Rd 94 Hi 422 221 i i-State 270 Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Rand v r Emerson Chicago Downtown Central auk T 70 e Oakton National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Map Legend Hill 147 r Cook Co 213 and Marine/Foster (5200N) for the three public transit operations Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central Courts k Central 213 93 Maple College 201 Sheridan nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Holy 422 S 148 Old Orchard Gross 206 C Northwestern Univ Hobbie and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) Dee Family yman 270 Point Central St/ CTA Trains Hooker Wendell 22 70 36 Bellevue L in Northeastern Illinois: The Chicago olf Cr Chicago A Harrison 54A 201 Evanston 206 A 8 A W Sheridan Medical 272 egan osby Maple th Central Ser 423 201 k Illinois Center 412 GOLF Westfield Noyes Blue Line Haines Transit Authority (CTA), Metra and Antioch Golf Glen Holocaust 37 208 au 234 D Golf Old Orchard Benson Between O’Hare Airport, Downtown Newberry Oak W Museum Nor to Golf Golf Golf Simpson EVANSTON Oak Research Sherman & Forest Park Oak Pace Suburban bus. -

Pharmacy Address City Zip Code Phone Lovins Pharmacy 32 West Main Street Albion 62806 (618) 445-4907 Doubek Pharmacy, Inc

Pharmacy Address City Zip Code Phone Lovins Pharmacy 32 West Main Street Albion 62806 (618) 445-4907 Doubek Pharmacy, Inc. 11350 South Cicero Alsip 60803 (708) 293-1122 Osco Pharmacy #3098 12003 S. Crawford Alsip 60803 (708) 389-2725 Medicine Shoppe 2516 State Street Alton 62002 (618) 467-0825 Osco Drug #3466 968 Route 59 Antioch 60002 (847) 395-7101 Aurora Pharmacy 475 N. Farnsworth Avenue Aurora 60505 (630) 820-3360 Medical Park Pharmacy 330 Weston Avenue Aurora 60505 (630) 801-3200 Walgreens # 02123 1014 Farnsworth Avenue Aurora 60505 (630) 820-5699 Fagen Pharmacy #32 715 Dixie Highway Beecher 60401 (708) 946-6600 CVS Pharmacy 6830 4609 W. Main Street Belleville 62226 (618) 355-4853 Hideg Pharmacy Inc. 8601 West Main Street Belleville 62223 (618) 398-4400 Kmart Pharmacy #3914 156 S. Gary Ave. Bloomingdale 60108 (630) 307-8073 Carle Rx Express #14 1701 E. College Ave. Bloomington 61704 (309) 664-3250 Merle Pharmacy #1 203 E. Locust St. Bloomington 61701 (209) 828-2242 Wal-Mart Pharmacy #10-3459 2225 W. Market Street Bloomington 61704 (309) 828-8626 Osco Drug #3161/471 455 Main St., N.W. Bourbannais 60914 (815) 935-0630 Brighton Pharmacy 108 Ransom, P.O. Box 788 Brighton 62012-0788 (618) 372-3313 Walgreens #2635 5400 W. 79th Street Burbank 60803 (708) 499-3755 Kroger Pharmacy L-714 501 North Giant City Rd Carbondale 62902 (618) 549-9743 Wal-Mart Pharmacy #196 1450 E. Main St. Carbondale 62901 (618) 549-0709 CVS Pharmacy 2431 W. Main Carbondale 62901 (618) 549-9433 Family Drug 1205 S. Division Carterville 62918 (618) 985-2441 Pharmacie Shoppe, Inc 202 W. -

Central Tri-State Tollway Project

TRI-STATE TOLLWAY Central Tri-State Tollway Project CONSTRUCTION OVERVIEW Railway Bridge, as well as integrating Flex Lanes and SmartRoad technology. The Central Tri-State Tollway (I-294) is being reconstructed from Balmoral Avenue to 95th Street to provide congestion Northern Section: Balmoral Avenue to North Avenue relief, reconstruct old infrastructure to meet current and Work in the northern section began in June 2018 and is future transportation demand, and address regional needs. scheduled to be complete by the end of 2024. The Tollway Work in 2021 includes: will repair pavement and rebuild and widen roadway between Balmoral Avenue and North Avenue and deliver Roadway reconstruction, including between the O’Hare new SmartRoad infrastructure, as well as reconstruct Oasis and Wolf Road to provide five lanes in each direction; shoulders to accommodate Flex Lanes. between St. Charles Road and Wolf Road to provide six southbound lanes and five northbound lanes; between I-55 th Bridges carrying I-294 over Irving Park Road, Lawrence and 75 Street to provide five lanes in each direction; and Avenue and the Canadian National Railway in Schiller Park between LaGrange Road and 95th Street build five lanes in will be reconstructed, and improvements will be made to each direction. local crossroad bridges including Balmoral Avenue and Wolf Work to rehabilitate the Bensenville Railroad Yard Bridge. Road. Construction to reconfigure the I-290/I-88 Interchange As part of this work, the O’Hare Oasis over-the-road pavilion including new bridges over Butterfield Road, the CSX was removed in 2019 to accommodate roadway widening. Railroad and I-290 and construction of new lanes connecting The 7-Eleven fuel stations and parking lots remain and the northbound I-294 to I-290.