Home from Home? Seeking Sanctuary in Swansea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Newsletter of the Federation of Museums & Art Galleries Of

The newsletter of the Federation of Museums & Art Galleries of Wales April 2011 The 2010 Federation AGM, Llanberis In November each year the Federation holds its AGM in a prominent museum or gallery and alternates between North & South Wales. In 2010 the AGM was hosted by the National Slate Museum in Llanberis and the keynote speaker was the new Director General of Amgueddfa Cymru, David Anderson. The event took place in the museum’s Padarn Room, one of two available conference / education rooms. The Federation President, Rachael Rogers (Monmouthshire Museums Service) presented the Federation’s Annual Report for 2009/10 and the The Padarn Room, National Slate Honorary Treasurer, Susan Dalloe (Denbighshire Federation President, Rachael Rogers and keynote speaker, Museum, Llanvberis Director-General of NMW / AC, David Anderson, at the AGM Heritage Service) presented the annual accounts. Following election of Committee Members and other business, David Anderson then gave his talk to the Members. Having only been in his current post as Director General of Amgueddfa Cymru for six weeks, Mr Anderson not only talked of his career and museum experiences that led to his appointment but also asked the Federation Members for their contributions on the Welsh museum and gallery sector and relationships between the differing museums and the National Museum Wales. Following a delicious lunch served in the museum café, the afternoon was spent in a series of workshops with all Members contributing ideas for the Federation’s forthcoming Advocacy strategy and Members toolkit. The Advocacy issue is very important to the Federation especially in the current economic climate and so, particularly if you were unable to attend the AGM, the following article is to encourage your contribution: How Can You Develop an Advocacy Strategy? The Federation is well on its way to finalising an advocacy strategy for museums in Wales. -

The Future of Our Recorded Past

A Report Commissioned by the Library and Information Services Council (Wales) The Future of Our Recorded Past A Survey of Library and Archive Collections In Welsh Repositories By Jane Henderson of Collections Care Consultancy March 2000 Table of Contents Page No… Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. ii The Future of Our Recorded Past - a Summary............................................................... iii Preface........................................................................................................................ ...... vi 1 The Project Brief ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The LISC (Wales) Conservation and Preservation Group.......................................... 1 1.2 A Survey of the Preservation Status of Library and Archive Collections .................. 1 1.3 The Survey Method.................................................................................................... 2 2 Background................................................................................................................... .. 3 2.1 What is Preservation?.................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Why Preservation?...................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Do we Need to Preserve Everything? ........................................................................ -

Cross-Curriculum Learning with Swansea Cultural Venues

1 CROSS-CURRICULUM LEARNING WITH SWANSEA CULTURAL VENUES Led by experienced artist-educators with specialist knowledge April 2018 – March 2019 2 Cross-Curriculum Learning Experience for Schools 4Site is a one stop cultural shop for all schools in Swansea. Check out the exciting range of work and the exhibitions going on at the Dylan Thomas Centre, the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea Museum, and West Glamorgan Archives. We recommend reading through this pack prior to your visit and if you have any further questions, please contact the appropriate venue. This document contains all the practical information you will need to organise your schools cultural education sessions and benefit from your 4site membership. Dylan Thomas Centre Glynn Vivian Art Gallery [email protected] [email protected] 01792 463980 01792 516900 Swansea Museum West Glamorgan Archives [email protected] [email protected] 01792 653763 01792 636589 3 CONTENTS 1. Introduction Page 4 2. Venues Page 5 - Map - Information 3. Fees and Charges Page 10 - How to pay 4. How to Book Page 11 - Booking forms - Group Sizes 5. Planning your visit Page 15 - Access - Parking - Resources 6. Session Programmes Page 18 - Foundation - Key Stage 2 - Key Stage 2 + 3 - Key Stage 4 7. Funding Support Page 27 “Excellent information on Glynn “A wonderful educational visit Vivian. Excellent hands on and @swanseamuseum. We have interactive workshop. Every thoroughly enjoyed our topic on opportunity taken to develop Ancient Egypt #Year1&2” pupils’ art skills: Sketching, observing, problem solving, Teacher, St Helen’s Catholic drawing.” Primary School Teacher, YGG Bryniago 4 1. -

Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: an American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Elizabeth C

Student Publications Student Scholarship 3-2013 Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Elizabeth C. Williams Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Nonfiction Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Williams, Elizabeth C., "Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties" (2013). Student Publications. 61. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/61 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 61 This open access creative writing is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Abstract This paper is a collection of my personal experiences with the Welsh culture, both as a celebration of heritage in America and as a way of life in Wales. Using my family’s ancestral link to Wales as a narrative base, I trace the connections between Wales and America over the past century and look closely at how those ties have changed over time. The piece focuses on five location-based experiences—two in America and three in Wales—that each changed the way I interpret Welsh culture as a fifth-generation Welsh-American. -

Locws International

locws.qxd 29/7/03 4:13 pm Page 1 LOCWS INTERNATIONAL SWANSEA CENTRAL LIBRARY RIVER TAWE BRIDGE 26 CASTLE STREET SWANSEA CASTLE ST MARY’S CHURCH DYLAN THOMAS CENTRE SWANSEA MUSEUM RIVER TAWE MARITIME & INDUSTRIAL MUSEUM RIVER TAWE BARRAGE HELWICK LIGHTSHIP Publishers: Locws International THE GUILDHALL SWANSEA MARINA Swansea Museum SWANSEA OBSERVATORY Victoria Road Swansea SWANSEA BEACH SA1 1SN 1 locws.qxd 29/7/03 4:13 pm Page 2 Publication copyright: © Locws International 2003 Texts copyright: Tim Davies David Hastie Felicia Hughes-Freeland Emma Safe Artworks copyright: the artists Photography: Graham Matthews Andrew Dueñas Ken Dickinson Layout: Christian Lloyd Peter Lewis Printing: DWJ Colourprint Published by: Locws International Swansea Museum Victoria Road Swansea SA1 1SN ISBN 0-9545291-0-3 2 locws.qxd 29/7/03 4:13 pm Page 3 AUTHORS TIM DAVIES DAVID HASTIE FELICIA HUGHES-FREELAND EMMA SAFE ARTISTS ERIC ANGELS DAVIDE BERTOCCHI IWAN BALA ENRICA BORGHI MAUD COTTER ANGHARAD PEARCE JONES DOROTHY CROSS BRIGITTE JURACK TIM DAVIES ANNIE LOVEJOY PETER FINNEMORE ALICE MAHER ROSE FRAIN PAUL & PAULA HUGHES GERMAIN ANTHONY SHAPLAND DAVID HASTIE CATRIONA STANTON KAREN INGHAM GRACE WEIR PHILIP NAPIER DAPHNE WRIGHT TINA O’CONNELL BENOIT SIRE LOIS WILLIAMS CRAIG WOOD LOCWS 1 LOCWS 2 2 SEPTEMBER – 1 OCTOBER 2000 7 SEPTEMBER – 29 SEPTEMBER 2002 3 locws.qxd 29/7/03 4:13 pm Page 4 Working site-specifically places particular demands on an artist not experienced in quite the same way in other fields, in the sense that the work becomes part of the site, not reflective of it. The site, in this case anywhere in Swansea, becomes your potential studio and material. -

Scolton Manor Museum Where Pembrokeshire’S Past Meets Its Future

Scolton Manor Museum Where Pembrokeshire’s past meets its future. Pembrokeshire’s County Museum is located in a traditional Victorian country house near Haverfordwest, surrounded by 60 acres of park and woodland and is completed by an award- winning eco-centre. OPENING TIMES Summer season: Park: 9am – 5.30pm House: 10.30am – 5.30pm Winter season: Park: 9am-4.30pm House: Closed ADmission Adult: £3 Manor House Children £2 Manor House Concessions: £2 Manor House Contact DetaiLS Scolton Manor Museum, Bethlehem, Havorfordwest, Pembrokeshire, SA62 5QL Manor House: 01437 731328 [email protected] Events 07.10.14 - Woodland tour VISIT WEBsite http://www.pembrokeshirevirtualmuseum. co.uk/content.asp?nav=3502,3503&parent_ directory_id=101 Big Pit: The National Coal Museum of Wales Big Pit is a real coal mine and one of Britain’s leading mining museums Big Pit is a real coal mine and one of Britain’s leading mining museums. With facilities to educate and entertain all ages, Big Pit is an exciting and informative day out. Enjoy a multi- media tour of a modern coal mine with a virtual miner in the Mining Galleries, exhibitions in the Pithead Baths and Historic colliery buildings open to the public for the first time. All of this AND the world famous underground tour! OPENING TIMES 9.30am-5pm ADmission FREE – Car parking £3 per day Contact DetaiLS Big Pit National Coal Museum, Blaenafon, Torfaen, NP4 9XP Tel: 02920 573650 VISIT WEBsite https://www.museumwales.ac.uk/bigpit/ National Museum Cardiff Discover art and the geological evolution of Wales With a busy programme of exhibitions and events, we have something to amaze everyone, whatever your interest – and admission is free! Although this is not the oldest of Amgueddfa Cymru’s buildings, this is the first location of the National Museum of Wales, officially opened in 1927. -

The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Half

THE GLAMORGAN-GWENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST TRACK 1 0 0 . 9 5 7 9 9 0 . 9 m 5 9 9 9 9 . 0 . 5 8 8 7 0 m 0 . 0 5 0 m 0 0 0 m 0 m m m Area of rock outcrop T R A 10 C 0.0 K 0m 9 6 .5 0 m 100.00m 9 9.5 0m 9 6 . 9 0 9 8. 9. 0 50 00 m m m G R Chamber A Chamber B ID N 0 30metres Plan of Graig Fawr chambered tomb showing chambers A and B, and the possible extent of the cairn area (shaded) HALF-YEARLY REVIEW 2007 & ANNUAL REVIEW OF PROJECTS 2006-2007 ISTER G E E D R GLAMORGAN GWENT IFA O ARCHAEOLOGICAL R N G O TRUST LTD I A T N A I S RAO No15 REVIEW OF CADW PROJECTS APRIL 2006 — MARCH 2007 ................................................... 2 GGAT 1 Heritage Management ....................................................................................................... 2 GGAT 43 Regional Archaeological Planning Services .................................................................... 9 GGAT 61 Historic Landscape Characterisation: Gower Historic Landscape Website Work. ........ 11 GGAT 67 Tir Gofal......................................................................................................................... 12 GGAT 72 Prehistoric Funerary and Ritual Sites ............................................................................ 12 GGAT 75 Roman Vici and Roads.................................................................................................. 14 GGAT 78 Prehistoric Defended Enclosures .................................................................................. 14 GGAT 80 Southeast Wales Ironworks.......................................................................................... -

The Swansea Branch Chronicle 1

Spring 2013 Issue No 1 Free to members £1 to non-members Waterloo Street junction Swansea at War Historical Association, Swansea Branch Promoting History in South West Wales From the Editor Welcome to our first edition of Chronicle. Message from the President Swansea Branch of the HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION is one of the liveliest in the country. This vitality owes much to a true ‘association’ with the National Waterfront Museum and its congenial meeting facilities– and, soon, a new lecture theatre. The friendly gossip before lectures and discussion afterwards seem The Journal not only to be read by you, but, written uninhibited; they encourage by you. We will concentrate on different periods of togetherness, which this newsletter history and for every edition we will be asking you, will also surely do. the members of the Historical Association, not just the academics, to send in contributions. Next edition… Success comes from the audience: ‘Medieval times’. a broad range of people simply interested in history, and the range Margaret McCloy of expert talks, from classical times to the contemporary world, with no agenda other than to entertain, inform and educate. Shakespeare wrote ‘There is a history in all men’s lives’. From the Chairman Moreover, the revival of Swansea’s branch has been an entirely The Swansea Branch, founded in 1926, has had its voluntary enterprise of enthusiastic ups and downs, a down happening in the 90s when historians, individuals, some the Branch virtually ceased to exist. However, it professional, some not, but all was revived in 2009, inspired by the interest in local committed – through a hard-working and family history evident in the activity of local committee ? to bringing their own history societies, and in the annual book fair held in enthusiasm and sense of history to Swansea Museum. -

Foundation Phase / Key Stage 1

Summer Term 2016 See inside for news, educational sessions, booking details, exhibitions and events. 1 Swansea Museum - Foundation Phase Topic: Mrs. Mahoney Mrs Mahoney was the wife of the museum caretaker in the 1850s, who was sacked for embezzling money. The Mahoney family lived in the museum and had to leave their home. Your class will meet Mrs. Mahoney who shares her sad story in costume and character. The story is illustrated through many objects. The children will see the trunk of things she is taking with her which show the difference between her way of life and theirs. Suggested age group: Yr 1 - 2, Duration: 1 hour Topic: Electricity and before A session that looks at homes and daily life, and the changes in these over the last 150 years. An active, taught session, using a lot of handling objects from today and the past and studying the differences. Changes in daily life are clearly demonstrated by examining hair tongs washing, irons, lighting and cleaning artefacts. Come and see a ‘Magic Lantern’ at work!! If you would like time for sketching and drawing after session or space for lunch please let me know at time of booking. Suggested age group: Rec - Yr 2 Duration: 1 hour 2 Swansea Museum - Foundation Phase Topic: Transport Tours A chance for schools to get a “behind the scenes” visit to the Swansea Museums Store, which is a very big warehouse near the Park & Ride car park at Landore. The children will be given a guided tour of the vehicles looking at changes and differences between them. -

Peter Finnemore

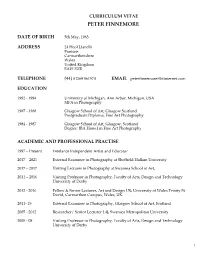

CURRICULUM VITAE PETER FINNEMORE DATE OF BIRTH 5th May, 1963 ADDRESS 24 Heol Llanelli Pontiets Carmarthenshire Wales United Kingdom SA15 5UB TELEPHONE (44) 01269 861570 EMAIL [email protected] EDUCATION 1992 - 1994 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA MFA in Photography 1987 - 1988 Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow Scotland Postgraduate Diploma, Fine Art Photography 1984 - 1987 Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow, Scotland Degree: (BA Hons.) in Fine Art Photography ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL PRACTISE 1997 – Present Freelance Independent Artist and Educator 2017 – 2021 External Examiner in Photography at Sheffield Hallam University 2017 – 2017 Visiting Lecturer in Photography at Swansea School of Art, 2011 – 2016 Visiting Professor in Photography, Faculty of Arts, Design and Technology University of Derby 2012 - 2016 Fellow & Senior Lecturer, Art and Design (.5), University of Wales Trinity St David, Carmarthen Campus, Wales, UK. 2011- 15 External Examiner in Photography, Glasgow School of Art, Scotland 2005 - 2012 Researcher/ Senior Lecturer (.4), Swansea Metropolitan University 2005 - 08 Visiting Professor in Photography, Faculty of Arts, Design and Technology University of Derby 1 2009 -12 Phd External Supervisor (University of Wales Newport) Geraint Davies; Dimensions, Perceptions: Resonances from Durer’s MELENCOLIA I (2012). 2007 - 2009 Welsh Language Fellow of the Welsh National College– Photography (.5) University of Wales, Newport 2000 – 2005 Part Time Lecturer, Photography, Swansea Institute of Higher Education -

Swansea Bay Holiday Guide.Pdf

HYOLOIDAYU GURIDE THANKS FOR BROWSING THE WEBSITE Holiday Guide for Lori 360 Beach and Watersports 360 Beach & Watersports is a unique multisport facility situated at the heart of Swansea Bay. Phone number: 01792 655844 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.360swansea.co.uk Postal address: Mumbles Road Swansea SA2 0AY Visit Swansea Bay Official Partner 360 Café Bar Whether you've had a full on kite surf session, are relaxing on the beach or taking your daily walk, 360 café is the perfect place to relax. Phone number: 01792 655844 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.360swansea.co.uk Postal address: 360 Beach and Watersports Mumbles Road Swansea SA2 0AY Visit Swansea Bay Official Partner Café TwoCann Award winning, family run café, bar and restaurant, located in a grade 2 listed building in SA1 Swansea Waterfront. Phone number: 01792 458000 Website: www.cafetwocann.com Postal address: Café TwoCann Unit 2, J Shed King's Road Swansea SA1 8PL Visit Swansea Bay Official Partner Dinner at Dylan's Enjoy an Edwardian evening dinner at 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, birthplace and family home of Dylan Thomas. Phone number: 01792 472555 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.dylanthomasbirthplace.com Postal address: Dylan Thomas Birthplace & Family Home 5 Cwmdonkin Drive Uplands Swansea SA2 0RA Visit Swansea Bay Official Partner Fairyhill Restaurant Fairyhill. A contemporary country house hotel, with an award- winning restaurant and a wine cellar of international repute. Phone number: 01792 390139 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.fairyhill.net Postal address: Fairyhill Reynoldston Gower Swansea SA3 1BS Visit Swansea Bay Official Partner Gower Adventures Open all year round offering a wide range of exciting outdoor adventure activities based around the Gower Peninsula. -

Organisations with Maritime Connections

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales VERSION 03 Organisations with Maritime Interests February 2017 Maritime Organisations with Maritime Interests Welsh Government: Cadw, Welsh Government Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed, Parc Nantgarw, Cardiff CF15 7QQ Tel. 01443 336000 [email protected] www.gov.wales/cadw Coastal and Maritime Archaeology: http://cadw.gov.wales/historicenvironment/protection/maritimewrecks/?l ang=en Wrecks and Wreck: http://cadw.gov.wales/historicenvironment/protection/maritimewrecks/wr ecksnwreck/?lang=en Designated Historic Shipwrecks of Wales: http://cadw.gov.wales/historicenvironment/protection/maritimewrecks/wr ecksnwreck/wreckswales/?lang=en Welsh Government Sponsored Bodies: National Library of Wales Ffordd Penglais, Aberystwyth, SN23 3BU Tel: 01970 632800 [email protected] https://www.llgc.org.uk/ Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales National Museum Cardiff, Cathays Park, Cardiff, CF10 3NP 1 A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales VERSION 03 Organisations with Maritime Interests February 2017 Maritime http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/enquiries/ http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/cardiff/ Department of History & Archaeology: Tel: (029) 2057 3229/3223 PAS Cymru: [email protected]; 029 2057 3226 Natural Resources Wales c/o Customer Care Centre, Ty Cambria, 29 Newport Road, Cardiff CF24 0TP Tel: 0300 065 3000 [email protected] http://naturalresources.wales/ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales RCAHMW, Ffordd Penglais, Aberystwyth, SY23 3BU Tel. 01970 621200 [email protected] www.rcahmw.gov.uk National Monuments Record of Wales [email protected] www.coflein.gov.uk 2 A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales VERSION 03 Organisations with Maritime Interests February 2017 Maritime Welsh Archaeological Trusts: Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust 41 Broad Street, Welshpool SY21 7RR Tel.